Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2003;13(4):2-5

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

GWL Chan, GS Ungvari, DTL Shek, JP Leung*

Abstract

Objective: Most studies have found no deterioration in patients’ quality of life following discharge to community-based settings with patients’ satisfaction with their living conditions usually increasing. There is a lack of longitudinal studies on the impact of community resettlement on the quality of life of Chinese psychiatric patients. This study examined changes in the quality of life of Hong Kong Chinese patients during a 12-month follow-up period following their discharge to halfway houses.

Patients and Methods: Twenty one patients with chronic schizophrenia were assessed before and every 2 months after their discharge to a halfway house, measuring objective and subjective quality of life indices and psychiatric symptoms with the following instruments: Satisfaction With Life Scale, the World Health Organization Quality of Life Measure-Abbreviated Hong Kong Chinese Version, Life Events List, Global Assessment Scale, and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

Results: While there was significant improvement in objective quality of life indices following discharge to halfway houses, most subjective quality of life indices remained unchanged except for satisfaction with the living environment, which significantly decreased. No significant improvement was observed in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale total scores.

Conclusion: The subjective component of quality of life for Chinese patients did not improve with community placement, suggesting that socio-cultural factors play an important role in determining quality of life for patients with chronic schizophrenia.

Key words: Community care; Deinstitutionalization; Quality of life; Schizophrenia

Dr GWL Chan, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

GS Ungvari, MD, PhD, FHKCPsych, FRANZCP, FRCPsych, Professor, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

DTL Shek, PhD, Professor, Department of Social Work, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

JP Leung, PhD, Department of Psychology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

* The Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists regrets to inform that

Dr JP Leung passed away in December 2002.

Address for correspondence:

Submitted: 14 August 2003; Accepted: 15 December 2003

Introduction

Although there has been a lack of well-designed prospective studies examining the impact of deinstitutionalisation on the quality of life (QOL) of psychiatric patients, it is a commonly held view that community placement improves patients’ overall positive feelings towards life, despite its limited effects on psychiatric symptoms.1,2 A recent review of QOL concluded that no study had reported negative effects of community placement on the QOL of discharged patients.3 Moreover, in some longitudinal studies, patients reported increased levels of satisfaction when living in the community.4,5 This positive impact on the patients’ perception of the living environment was also noted in the British study of deinstitutionalisation conducted by Leff et al.6 Applicability of these findings to the Chinese socio- cultural context is uncertain, since the very concept of QOL is culture-sensitive.7 However, there have been no systematic studies concerning the impact of community resettlement on the QOL of Chinese patients with schizophrenia.8

The present study adopted a longitudinal design to examine the change in QOL in a group of Chinese patients with schizophrenia in Hong Kong, as they moved from hospitals to halfway houses (HWHs).

Patients and Methods

Patients

All patients in the pre-discharge ward of 4 psychiatric hospitals who met the following inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study:

- Chinese ethnicity and fluency in the Cantonese dialect

- age between 18 and 60 years

- diagnosis of schizophrenia according to DSM-IV9

- duration of illness of at least 5 years

- selected to be discharged to a HWH

- willingness to give consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria included current or past history of drug and substance abuse, and ongoing acute medical or neurological conditions. This is because drugs and alcohol can exacerbate the psychiatric symptoms that can affect the QOL, as can medical conditions.10-12

Procedures

Before the patients were discharged to a HWH, they were assessed at 2-monthly intervals, using the assessment tools described later. The number of pre-discharge assessments for individual patients ranged from 2 to 6, depending on the length of time between their recruitment in the study and their discharge to a HWH. Patients continued to be assessed every 2 months during the year following discharge, employing the same instruments that were used in the pre- discharge evaluation.

Assessment Instruments

QOL assessment included subjective well-being, global functioning, and contextual factors such as living circumstances and income.13 Subjective well-being was classified as a subjec- tive QOL index, while global functioning, living circumstances, and income were classified as objective QOL indices.

Subjective well-being was assessed by the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS)14 and the World Health Organization (WHO) Quality of Life Measure-Abbreviated Hong Kong Chinese Version [WHOQOL-BREF(HK)].15 Both the SWLS16 and WHOQOL-BREF(HK)15 have been found to have acceptable psychometric properties for the Hong Kong Chinese population. Cronbach’s alpha of the 5-item SWLS was 0.67. Cronbach’s alpha for the 4 domains in the WHOQOL-BREF (HK) ranged from 0.67 to 0.79, while the test-retest reliability, measured by intra-class correlation coefficient, ranged from 0.64 to 0.90.

Objective QOL indices were measured by 2 scales. Global level of functioning was assessed by the Global Assessment Scale (GAS).17 Contextual factors were assessed by the Life Events List (LEL). The LEL is an interview schedule that was developed by the principal author to assess both the routine and stressful daily living experiences that are encountered by patients. Items for the LEL were selected from the List of Recent Experiences,18 the Life Experiences Survey,19 and Lehman’s Quality of Life Interview Schedule.10 The LEL consists of 62 items comprehensively covering all kinds of daily life experiences, as well as con- ditions of residence, safety, work, finance, social contacts, legal issues, recreation, illness, bereavement, and accidents. Subjects’ reported scores for these experiences are added to provide the total LEL score. The test-retest reliability of the LEL, measured by intra-class correlation coefficient, was 0.645.

Patients’ incomes in the past year were obtained from case social workers, medical records, and/or bank books.

The 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)20 was used to assess the presence and severity of psychiatric symptoms.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 9. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients were summarised using descriptive statistics. Both Mann-Whitney U test and chi-square test were used to calculate the differences in socio-demographic and clinical variables between patients who remained in a HWH and those who dropped out of the study. The Friedman test was used to examine changes in the QOL indices and psychiatric symptoms of patients after discharge, particularly whether there were any changes in QOL indices and psychiatric symptoms throughout the study period.

Results

During the study period, 25 patients were discharged from 4 hospitals to HWHs. Of the 25 patients, 4 dropped out of the study: 1 was readmitted to hospital, 1 moved back home, 1 moved overseas, and 1 broke the rules of the HWH and moved out. At the end of the 12-month follow-up period, 21 patients remained in HWHs. The mean age of the discharged patients was 40.40 ± 7.83 years (range, 23 to 54 years); 56% of the patients were men (n = 14) and 44% were women (n = 11); 18 patients (72%) were single, 6 (24%) were separated, divorced, or widowed, and 1 (4%) was married. Twelve percent of patients were illiterate, 12% had received primary education, and 76% had secondary education or above. The duration of illness was 15.40 ± 7.18 years (range, 6 to 30 years). The number of admissions to hospital was 5.08 ± 3.15 (range, 1 to 12).

Quality of Life Indices

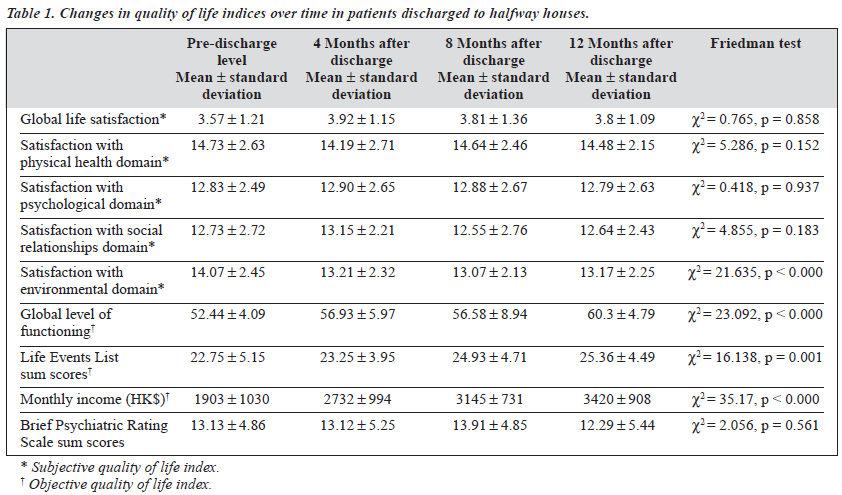

There were no significant differences in QOL indices among the group of patients remaining in HWHs and those leaving HWHs. The objective QOL indices (global level of functioning, total life events, and income) significantly increased after the patients were discharged to HWHs. The subjective QOL indices did not show any significant differences between the 2 settings. The satisfaction with environment domain significantly decreased after the patient’s discharge to a HWH. No significant improvement was observed in BPRS total scores over the follow-up period (Table 1).

Discussion

The results of this study conducted in a Chinese socio- cultural context, only partly support the commonly held view that there is no deterioration in the QOL of chronic psychiatric patients after their discharge to community settings.3 In this study, objective QOL indices improved after discharge. However, satisfaction with the environment significantly decreased after patients settled into HWHs,

despite the comfort and privacy these settings provide. The discrepancy between our findings and those of western studies might be due, in part, to the broader conceptualisation of living environment in our study. Under living environ- ment, we included security, pollution, noise, traffic, climate, financial resources, accessibility and quality of health and social care, access to information, skills, leisure activity, and overall satisfaction with the environment.15 Most studies have adopted a considerably narrower concept, considering only aspects of freedom, autonomy, comfort, and the privacy of the living environment.3,21,22

The other explanation may be due to the following conditions: inadequate attention to the stress of community living and the management problem of HWHs. The HWH is still considered to be a mini-institution in the community,23 so the degree of freedom in a HWH and the extent of integration into the community may not be intensive enough to promote subjective satisfaction with the environment. However, the level of freedom and privacy in a HWH is greater than those in a hospital; the less restrictive environment in a HWH should at least maintain QOL rather than decrease it.24 Therefore, inadequate attention to the stress of community living is a more likely condition that counteracts the greater freedom and privacy in a HWH resulting in a decrease in QOL.

In addition, the characteristics of Chinese culture may help to explain our findings. Freedom, autonomy, and independence that are fostered by community living might be more important for psychiatric patients in industrialised western societies.25 Chinese psychiatric patients who are brought up in a society that emphasises interdependence, deference, compliance, and cooperation with others tend to value the security provided by a hospital and depend more on families and hospital staff to meet their needs.26-28 The importance of cultural factors was clearly demonstrated in a recent cross-cultural study,29 which found that subjective well-being in Asian students was associated with inter- dependence, while American students valued independence and disengagement of the self.

Limitations of the Study

Major limitations of this pilot study, which restrict the generalisability of our findings, include the small sample size and the lack of a matched control group. The refusal rate was fairly high, further reducing the generalisability of the study. These limitations were partly offset by the strengths of the study, particularly the longitudinal design that is more effective in controlling the influence of personal characteristics on dependent variables. This pilot study constitutes the first step in opening up longitudinal cross- cultural studies of QOL.

Conclusion

There have been few systematic longitudinal studies of the impact of community resettlement on the QOL of Chinese psychiatric patients to the best of our knowledge. Recent reviews of western studies of deinstitutionalisation have emphasised both the maintenance effects of community placement and even the positive impact of community resettlement on the satisfaction with living conditions for patients discharged from hospital in some longitudinal studies.3 It remains to be seen whether these results can be replicated in longitudinal studies when employing a wider range of QOL measures and involving a larger sample. While some of our findings are consistent with those reported in the western literature, the observation that there was a significant decrease in satisfaction with the living environment during a 1-year follow-up period suggests that cross-cultural differences should be taken into account in the assessment of QOL in psychiatric patients. In view of the lack of data on the effects on deinstitutionalisation in Chinese societies, further studies in this area are clearly warranted.

References

- Bachrach LL. Lessons from the American experience in providing community-based services. In: Leff J, editor. Care in the community. Illusion or reality? Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1997:21-36.

- Sastorius N. Quality of life and mental disorders: a global perspective. In: Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N, editors. Quality of life in mental disorders. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1997:319-328.

- Barry MM, Zissi A. Quality of life as outcome in evaluating mental health services: a review of the empirical evidence. Soc Psychiat Psychiatr Epidemiol 1997;32:38-47.

- Barry MM, Crosby C. Quality of life as an evaluative measure in assessing the impact of community care on people with long-term psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1996;168:210-216.

- Warner R. Alternatives to the hospital for acute psychiatric treatment. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1995.

- Leff J, Dayson D, Gooch C, Thornicroft G, Wills W. Quality of life of long-stay patients discharged from two psychiatric institutions. Psychiatr Serv 1996;47:62-67.

- 7. Heinze M, Taylor RE, Priebe S, Thornicroft G. The quality of life of patients with paranoid schizophrenia in London and Berlin. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1997;32:292-297.

- Chan GWL, Ungvari GS, Leung JP. Residential services for psychiatric patients in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2001;11:13-17.

- 9. American Psychiatric Association diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Associ- ation; 1994.

- Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plan 1998;11:51-62.

- Sullivan G, Wells KB, Leake B. Clinical factors associated with better quality of life in a seriously mentally ill population. Hosp Comm Psychiatry 1992;43:794-798.

- 12. Browne S, Roe M, Lane A, et al. Quality of life in schizophrenia: relationship to socio-demographic factors, symptomatology and tardive dyskinesia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;94:118-124.

- Katschnig H. How useful is the concept of quality of life in psychiatry? In: Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N, editors. Quality of life in mental disorders. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1997:3-16.

- Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assessment 1985;49:71-75.

- Hong Kong Project Team on the Development of the Hong Kong Version WHOQOL. Hong Kong Chinese Version World Health Organization Quality Of Life Measure Abbreviated Version. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 1997.

- Leung JP, Leung K. Life satisfaction, self-concept, and relationship with parents in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 1992;21:653-665.

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The Global Assessment Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976;33:766-771.

- 18. Henderson S, Byrne DG, Duncan-Jones P. Neurosis and the social en Sydney: Academic Press; 1981.

- Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the impact of life changes: development of the Life Experiences Survey. J Consult Clin Psychol 1978;46: 932-946.

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962;10:799-812.

- Lehman AF, Possidente S, Hawker F. The quality of life of chronic patients in a state hospital and in community residences. Hosp Comm Psychiatry 1986;37:901-907.

- Simpson CJ, Hyde CE, Faragher EB. The chronically mentally ill in community facilities: a study of quality of life. Br J Psychiatry 1989;154: 77-82.

- Yip KC, Cheung HK, Pang HT. Community psychiatric services. In: Mak KY, Chan CKY, Lo TL, Ng TMY, Yip KS, editors. Mental health in Hong Kong, 1996/97. Hong Kong: Mental Health Association of Hong Kong; 1998:77-83.

- Lehman AF, Slaughter JG, Myers CP. Quality of life in alternative residential settings. Psychiatr Quart 1991;62:35-69.

- Chan GWL, Ungvari GS, Shek DTL, Leung JP. Hospital and community based care for people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong: quality of life and its correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38:196-203.

- Redding G, Wong GYY. The psychology of Chinese organizational behavior. In: Bond MH, editor. The psychology of the Chinese people. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1995:19-39.

- Yang KS. Chinese social orientation: an integrative analysis. In: Lin TY, Tseng WS, Yeh EK, editors. Chinese societies and mental health. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1995:19-39.

- Bond MH. Chinese values. In: Bond MH, editor. The handbook of Chinese psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1996: 208-226.

- Kitayama S, Markus HR, Kurokawa M. Culture, emotion, and well- being: good feelings in Japan and the United States. Cognition Emotion 2000;14:93-124.