East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:131-41

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prof. Sandeep Grover, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Dr Natasha Kate, MD, Former Senior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Prof. Subho Chakrabarti, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Prof. Ajit Avasthi, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Address for correspondence: Prof. Sandeep Grover, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh 160012, India. Tel: (91-172) 2756 807; Fax: (91-172) 2744 401 / 2745 078; Email: drsandeepg2002@yahoo.com

Submitted: 7 November 2016; Accepted: 14 August 2017

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the positive aspects of caregiving and its correlates (socio-demographic and clinical variables, caregiver burden, coping, quality of life, psychological morbidity) in the primary caregivers of patients with bipolar affective disorder (BPAD).

Methods: A total of 60 primary caregivers of patients with a diagnosis of BPAD were evaluated on the Scale for Positive Aspects of Caregiving Experience (SPACE) and the Hindi version of Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire, Family Burden Interview Schedule (FBIS), modified Hindi version of Coping Checklist, shorter Hindi version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF), and Hindi translated version of 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12).

Results: Caregivers of patients with BPAD had the highest mean score in the SPACE domain of Motivation for caregiving role (2.45), followed by Caregiver satisfaction (2.38) and Caregiving personal gains (2.20). The mean score was the lowest for the domain of Self-esteem and social aspect of caring (2.01). In terms of correlations, age of onset of BPAD had a negative correlation with various domains of SPACE. The mean number of total lifetime affective and depressive episodes correlated positively with Self-esteem and social aspect of caring. Caregiver satisfaction correlated negatively with FBIS domains of Disruption of routine family activities, Effect on mental health of others, and subjective burden. Coercion as a coping mechanism correlated positively with domains of Caregiving personal gains, Caregiver satisfaction, and the total score on SPACE. Three (Physical health, Psychological health, Environment) out of 5 domains of the WHOQOL-BREF correlated positively with the total SPACE score. No association was noted between GHQ-12 and SPACE scores.

Conclusion: Positive caregiving experience in primary caregivers of patients with BPAD is associated with better quality of life of the caregivers.

Key words: Bipolar affective disorder; Caregivers

Introduction

Bipolar affective disorder (BPAD) is a chronic, relapsing condition which is associated with significant negative outcomes for patients and their caregivers. Negative outcomes for the patient include work dysfunction,1,2 educational problems,3 marital failure, interpersonal relationship problems,4,5 neurocognitive deficits,6 suicidality,7 financial problems,8 substance abuse,9-11 residual symptoms in between the episodes,12 poor quality of life (QOL),13 disability,14 stigma,15 cardiovascular morbidity,16 and premature mortality.17 The impact on caregivers has been evaluated in the form of caregiver burden, poor QOL, stigma, psychological morbidity, poor physical health, distress, and financial constraints.18-23

However, in recent times, studies have also begun to evaluate the positive aspects of caregiving (PAC) among caregivers of patients with severe mental disorders. Most of the literature on PAC is related to dementia and end-of-life care. These studies have shown that caregivers experience subjective gains and satisfaction.24,25

Only occasional studies have evaluated PAC among the caregivers of patients with BPAD. A study from our centre evaluated PAC using the Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI),23 which assesses caregiving appraisal using the framework of stress-appraisal coping. The inventory has 10 domains, 8 of which assess negative aspects of caregiving and 2 evaluate PAC. A study showed that when compared with caregivers of patients with schizophrenia, their counterparts with BPAD have lower rated positive personal experiences.23 This study also showed a significant positive correlation between positive and negative caregiving appraisal, and did not find any association of PAC with socio-demographic variables of patients and caregivers, clinical profile of the patients, or psychological morbidity assessed by General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) among caregivers.23 However, it is important to note that the assessment of PAC in the ECI is not comprehensive. Another qualitative study which evaluated PAC in the form of rewards among the adult children of parents with BPAD reported intensification of the relationship as a reward of caregiving.26

When one evaluates the data on PAC among caregivers of patients with various psychiatric disorders, it is evident that most of the data on PAC come from qualitative studies and that there have been some attempts to design scales and questionnaires to assess various aspects of PAC. The available scales include the positive caregiving experience domain of the ECI,27 Caregiving Satisfaction Scale,28 Caregiving Gains Scale,29 the Finding Meaning Through Caregiving Scale,30 and the PAC Scale.31 Many of these scales evaluate 1 or 2 aspects of PAC. Recently, the Scale for Positive Aspects of Caregiving Experience (SPACE) was designed by taking the items from various existing scales and validating the scale among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia.32

Given the lack of data on PAC among caregivers of patients with BPAD, the present study aimed to assess PAC (using SPACE) and its correlates (socio-demographic and clinical variables, caregiver burden, coping, QOL, and psychological morbidity) in the primary caregivers of patients with BPAD. According to the null hypothesis, it was hypothesised that PAC would not be related to any of the other caregiver variables.

Methods

This study was conducted in a multispecialty tertiary care hospital in north India. The Ethics Review Committee of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India provided ethical approval for the study. Patients and caregivers were recruited after obtaining written informed consent. Patients were included in the study if they had a diagnosis of BPAD as per the DSM- IV33 (by Mini-International Neuropsychiatry Interview [MINI]34); aged between 18 and 65 years; illness duration of at least 1 year and currently in remission (i.e. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS]35 score of ≤ 7 and Young Mania Rating Scale [YMRS]36 score of < 8). Patients with co-morbid chronic physical, psychiatric and substance dependence (except tobacco dependence) and organic brain syndromes were excluded.

Primary caregivers were included in the study if they were aged ≥ 18 years, continuously involved in the care of the patient for at least 1 year, not diagnosed with a physical or psychiatric disorder (other than tobacco dependence), and able to read Hindi and / or English. A caregiver was considered the primary caregiver if she / he was living with the patient and was involved in the care of the patient for at least 1 year, such as looking after the patient’s daily needs and medications, supervision of medication intake, bringing the patient to hospital, staying with the patient during hospital stay, and involved in maintaining liaison with hospital staff.

Patients with another family member with a diagnosed psychiatric disorder or chronic physical illness staying in the same dwelling unit were excluded.

Sample and Instruments

The study included 60 patients with BPAD along with their caregivers selected by convenience sampling.

The MINI34 was used to confirm the diagnosis of BPAD and to rule out co-morbid psychiatric disorders. Patients were rated on HDRS35 and YMRS36 to assess remission and to evaluate the severity of residual psychopathology.

Scale for Positive Aspects of Caregiving Experience

The SPACE32 was developed at our institute. It comprises 44 items which assess the PAC experience. Each item was rated on a 5-point rating scale (0-4) and the 44 items were divided into 4 domains of positive caregiving: Caregiving personal gains, Motivation for caregiving role, Caregiver satisfaction, and Self-esteem and social aspect of caring. The mean score for each domain was obtained by dividing the total score of the domain by the number of items included in the domain. The scale has shown good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.923), test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.81-0.99), cross- language reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.47- 0.97), split-half reliability (Guttman split-half coefficient, 0.834), and face validity (> 90%).32

Family Burden Interview Schedule

The Family Burden Interview Schedule (FBIS), developed by Pai and Kapur,37 is one of the most commonly used tools to evaluate family burden among caregivers of mental illnesses in India. The scale has good reliability (0.87) and validity (0.72).37

Hindi Version of Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire

The Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire38,39 was adapted and validated in Hindi. The Hindi version (Hindi-IEQ) is a self-rated questionnaire which evaluates the possible consequences of caring for a family member with severe mental illness.40 Factor analysis of the Hindi-IEQ included 29 items divided into 4 subscales: Tension (10 items), Worrying-urging I (10 items), Worrying-urging II (6 items), and Supervision (3 items). The Hindi version has good test- retest and split-half reliability.40

Global Assessment of Functioning Scale

Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) is a clinician-rated 100-point scale to rate the functioning of the subject in the social, occupational, and psychological domains. The scale has clear description of each 10-point intervals to rate the level of functioning. Rating was done on the basis of all available information. The scale was used to assess overall functioning relating to psychiatric symptoms.41

Hindi Version of Coping Checklist

The modified Hindi version42 of Coping Checklist developed by Scazufca and Kuipers43 was used to assess the coping of caregivers. It consists of 14 items divided into 5 subscales: Problem focused, Seeking social support, Avoidance, Coercion, and Collusion.

World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF

The shorter Hindi version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) is a 26-item multilingual instrument designed to assess QOL. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale with a total score range of 26 to 130. It emphasises the subjective evaluation of the respondent’s health and living conditions. The scale has 5 domains: General health, Physical health, Psychological health, Social relationships, and Environment. This scale has been found to have psychometric properties comparable to those of the full version (WHOQOL-100).44 The scale has good discriminant validity, concurrent validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability.45 A self-administered Hindi version of the instrument was used for this study.

Hindi Translated Version of the 12-Item General Health Questionnaire

Hindi translated version46 of the 12-item GHQ (GHQ-12)47 was used to assess psychological morbidity. A score of < 2 indicates the subject is free from any psychiatric illness.48

Procedure

Patients with a diagnosis of BPAD who were accompanied by a caregiver were contacted during their routine outpatient follow-up visits and were given information about the study. Those who provided written informed consent and fulfilled the selection criteria were recruited by convenience sampling. The patients were assessed on the HDRS, YMRS, and GAF. The FBIS was completed by a clinician based on a semi-structured interview with the primary caregiver. Caregivers completed the SPACE, Hindi-IEQ, Hindi version of Coping Checklist, the WHOQOL-BREF, and the Hindi version of the GHQ-12. Caregivers scoring of > 2 on the GHQ-12 were advised to seek formal psychiatry consultation.

Statistical Analysis

The SPSS (Windows version 14.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago [IL], US) was used to analyse the data. Mean and standard deviation were computed for continuous variables whereas frequency and percentages were computed for categorical and nominal variables. Correlation between PAC and other variables was assessed using Pearson’s product moment correlation and Spearman’s rank correlation. Comparisons were undertaken using the t test.

Results

Socio-demographic and Clinical Profiles

The mean (± standard deviation) age of patients was 38.53 ± 13.3 (range, 18-65) years and their mean duration of formal education was 11.88 ± 3.43 (range, 0-17) years. In all, 60% of the patients (n = 36) were male and about half (52%) were in paid employment. The majority of patients (77%) were married, Hindu (70%) by religion, and were from nuclear families (60%). Those from an urban locality (55%) outnumbered those from a rural locality. The mean family monthly income was US$371.0 ± 230.8 (range, US$116.7- 1167.0).

The mean age of caregivers was 44.52 ± 10.44 (range, 22-72) years and their mean duration of education was 12.73 ± 3.61 (range, 0-18) years. There was a slight preponderance of male caregivers (55%) and of those in paid employment (57%). The majority of caregivers were married (92%).

More than half of the caregivers (53%) were spouses and 28% were parents. A minor proportion of caregivers were children (13%), siblings (3%), and other relatives (3%). The caregivers were in the caregiving role for a mean of 9.36 ± 8.00 (range, 1-32) years and were spending 2.19 ± 1.35 (range, 0.5-7) hours per day in taking care of the patient.

The clinical profile of the patients is shown in Table The mean age of onset was 26.28 ± 10.24 years and the mean duration of illness was 12.16 ± 11.01 years. They had a mean of 6.75 ± 5.63 lifetime affective episodes. The mean number of lifetime hypomanic / manic / mixed episodes exceeded that of depressive episodes. Few patients (n = 6; 10%) had co-morbid substance dependence. The mean HDRS score was 1.83 and the mean YMRS score was 0.85. In terms of medications, half of the patients were receiving valproate and slightly more than one-third were receiving lithium. About half of the patients were receiving concomitant antipsychotic medications and 40% were concomitantly receiving antidepressants; about one-fifth were receiving benzodiazepines.

Positive Aspect of Caregiving

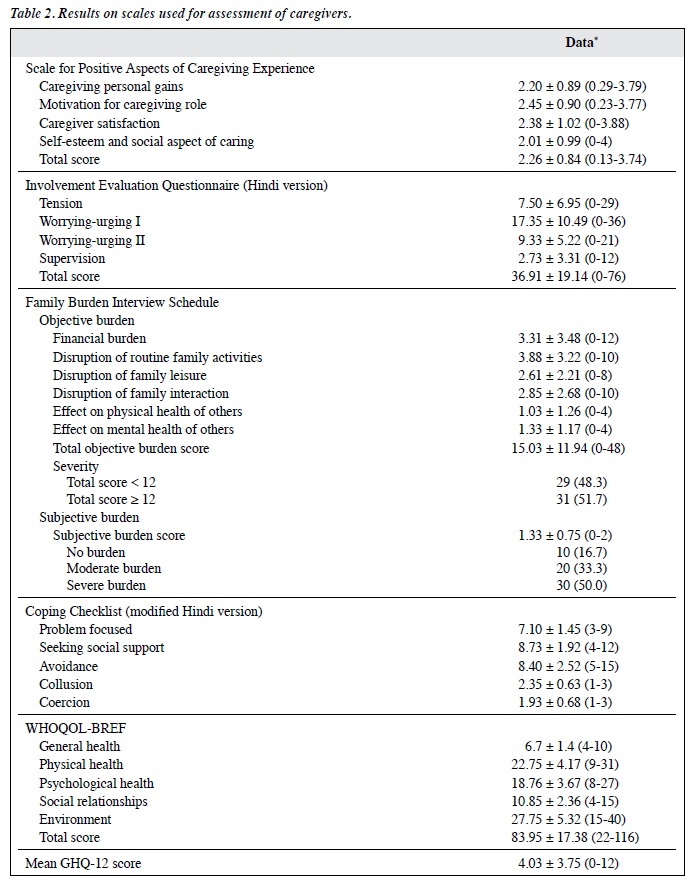

As shown in Table 2, the mean SPACE weighted score was highest for Motivation for caregiving role followed by Caregiver satisfaction and Caregiving personal gains. The mean score was lowest for Self-esteem and social aspect of caring. The mean total weighted score was 2.26 ± 0.84.

Caregiver Burden, Caregiving Consequence, and Coping

Caregiving consequences assessed by the Hindi-IEQ showed that the mean score was highest for the domains of Worrying-urging I followed by Worrying-urging II and Tension. The mean score was lowest for the domain of Supervision (Table 2).

* Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (range) or No. (%) of subjects.

† Twelve patients were receiving olanzapine, 8 on quetiapine, 4 on risperidone, 2 on chlorpromazine, and 1 each on amisulpride, aripiprazole, and trifluoperazine.

‡ Seven patients were receiving escitalopram, 5 each on sertraline and mirtazapine, 4 on bupropion, 2 on fluoxetine, and 1 each on venlafaxine and imipramine.

Abbreviations: GHQ-12 = 12-Item General Health Questionnaire; WHOQOL-BREF = Shorter version of World Health Organization Quality of Life.

* Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (range) or No. (%) of subjects.

Abbreviations: SPACE = Scale for Positive Aspects of Caregiving; WHOQOL-BREF = Shorter version of World Health Organization Quality of Life.

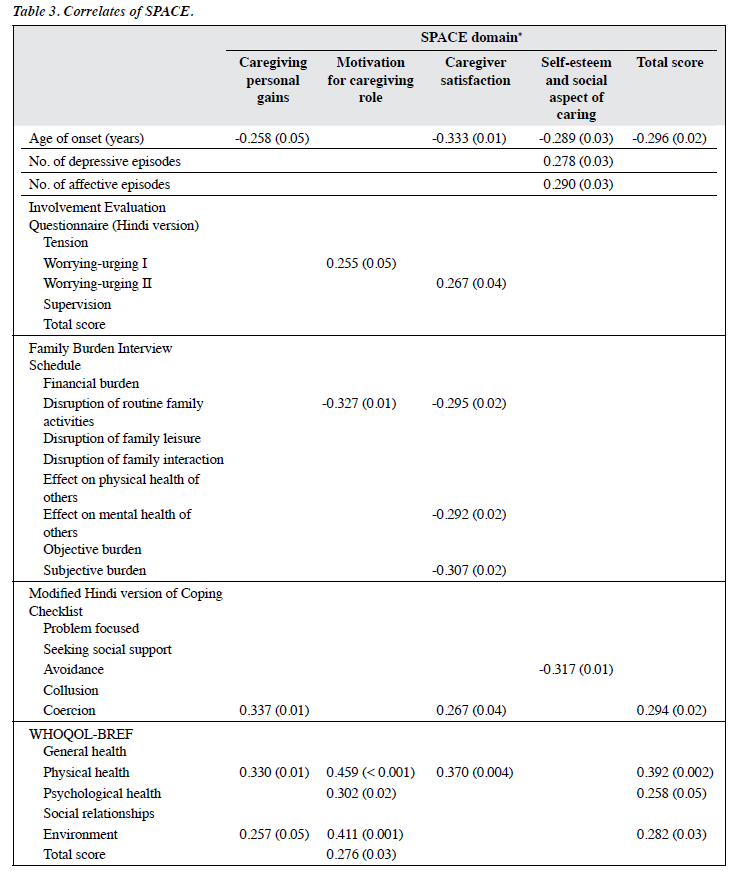

* Data are shown as correlation coefficients (p values).

The mean objective burden score on the FBIS was 15.03 and the subjective burden score was 1.33. Half of the caregivers reported severe subjective burden and a further one-third reported a moderate level of burden. More than half (51.7%) of the caregivers reported a severe objective burden (score ≥ 12).

On the modified Hindi version of Coping Checklist the mean score was highest for the domain of Seeking social support (8.73 ± 1.92) followed by Avoidance (8.40 ± 2.52) and Problem focused (7.10 ± 1.45). The lowest scores were found in domains of Collusion and Coercion.

The mean total WHOQOL-BREF score was 83.95 ± 17.38 with the highest score found in domain of Environment followed by Physical health.

The mean GHQ-12 score was 4.03 ± 3.75. Of the 60 caregivers, 38 (63%) had a GHQ-12 score of ≥ 2 and among them, the mean score was 6.12 ± 3.16 (range, 2-12), indicating a substantial level of morbidity.

Factors Associated with Positive Aspects of Caregiving

Analysis of mean scores on SPACE domains and total SPACE score showed no correlations with socio- demographic variables of patients and caregivers, with the exception of gender of the caregivers. Female caregivers had higher mean scores for Motivation for caregiving role than males (2.74 ± 0.55 vs. 2.22 ± 1.06; t = 2.28; p = 0.03).

Positive aspects of caregiving, as assessed by SPACE, did not correlate with time spent in caregiving per day and duration since in caregiver role, with the exception of a positive correlation between duration since in caregiver role and Self-esteem and social aspect of caring (Pearson correlation coefficient, 0.298; p = 0.02).

Duration of illness, total number of manic / hypomanic / mixed episodes, HDRS score, YMRS score, and GAF showed no significant correlation with SPACE. As shown in Table 3, a higher number of lifetime affective and depressive episodes correlated positively with Self- esteem and social aspect of caring. Age of onset correlated negatively with 3 out of the 4 SPACE domains and the total SPACE score. In terms of caregiver burden and coping, few correlations were seen between these variables and various domains of SPACE and the SPACE total score.

There was a positive correlation between the Hindi- IEQ domain of Worrying-urging I and the SPACE domain of Motivation for caregiving role, whereas Worrying-urging II correlated positively with Caregiver satisfaction.

No correlation was seen between total objective burden (FBIS) score and SPACE domains and total SPACE score. The subjective burden score correlated negatively with Caregiver satisfaction. There was a negative correlation between FBIS domain of Disruption of routine family activities and SPACE domain of Motivation for caregiving role. Caregiver satisfaction correlated negatively with FBIS domains of Disruption of routine family activities and Effect on mental health of others. There was no difference in mean scores of SPACE domains and total SPACE score when groups of those with an FBIS total objective burden score of ≥ 12 and < 12 were compared.

In terms of modified Hindi version of Coping Checklist, the most consistent positive correlations were seen between Coercion as a coping mechanism and various domains and the total score of SPACE. Avoidance as a coping mechanism correlated positively with Self-esteem and social aspect of caring’ domain.

Motivation for caregiving role domain of SPACE correlated positively with WHOQOL-BREF domains of General health, Physical health and Environment, and total WHOQOL-BREF scores. The Physical health domain also correlated positively with SPACE domains of Caregiving personal gains and Caregiver satisfaction. The WHOQOL- BREF domain of Environment correlated positively with the SPACE domain of Caregiving personal gains.

Association of Psychological Morbidity with Positive Aspects of Caregiving

There was no significant association between the GHQ-12 score and SPACE. No significant difference was seen in the mean scores of positive domains and total score between the GHQ-12 positive (GHQ score ≥ 2) and GHQ-12 negative (GHQ score < 2) groups.

Discussion

Positive aspects of caregiving have not received as much attention from researchers as the negative impact of caregiving. Positive aspects of caregiving are considered a subjective event and no standard formal definition is established. Researchers have attempted to integrate PAC into the same stress-coping model used to understand negative aspects of caregiving.49 Current understanding suggests that positive and negative aspects of caregiving are not opposite ends of the same continuum. Further, the data also suggest that the correlates and predictors of positive and negative aspects are often not the same.50 Accordingly, PAC appears to be a separate dimension of the caregiving experience. In view of this, the present study was carried out with the hypothesis that there would be no relationship between PAC and other caregiving variables, demographic variables, and clinical variables.

Studies among the caregivers of patients with dementia have identified PAC in the form of a sense of satisfaction and pride,51 emotional rewards,52,53 personal growth,54 self-respect,55 more self-awareness,56 sense of mastery or competency in the role of caregiving,51,52,54,56-58 improvement in the relationship (caregivers described gains relating to companionship and to being in the company of their husband or wife),51 greater emotional closeness,58 increased intimacy in the relationship,51,54 and reciprocity or the opportunity to give back to their loved one leading to satisfaction.51,53,54,58 However, it is important to note that many of these individual studies have assessed only a few aspects of PAC.

The SPACE is a more comprehensive instrument, which assesses PAC with 4 major domains. Accordingly, it provides more comprehensive assessment of PAC. It has been previously used in the evaluation of PAC in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia,59 dementia,60 and diabetes mellitus.61 The scale has much broader coverage and can be used for assessment of PAC among caregivers of patients with any chronic physical illnesses. However, the scale was developed in India and has not yet been used across different cultures.

Findings of the present study using SPACE show that mean scores were highest for Motivation for caregiving role followed by Caregiver satisfaction and Caregiving personal gains, and the score being lowest for Self-esteem and social aspect of caring. These findings suggest that personality and intrinsic factors are the most important determinants of taking up a caregiver role, rather than social aspects. When we compare the findings of the present study with previous studies, which used SPACE among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia59 and dementia,60 the mean scores on various domains are comparable with same hierarchy of scores obtained for various domains. This suggests that PAC are similar for the caregivers of patients of BPAD, schizophrenia, and dementia. However, the hierarchy for various domains observed for caregivers of patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus was different from those observed among the caregivers of various mental disorders. In caregivers of type 1 diabetes mellitus, the mean score was highest for the domain of Self-esteem and social aspect of caring followed by Caregiving personal gains, Caregiver satisfaction, and Motivation for caregiving role.61 These differences may be partially explained by the age of patients, relationship of caregiver with the patient, and clinical variables such as nature and course of the illness and type of treatment available. However, it can be hypothesised that some of these differences could be due to the caregiving expectations and roles the caregivers have in management of various physical illnesses and mental disorders.

Correlates of Positive Aspects of Caregiving

Findings of the present study showed a lack of association between SPACE and socio-demographic profile of the patients and caregivers, with the exception of female caregivers having higher mean scores for Motivation for caregiving role. A previous study which evaluated PAC using ECI among caregivers of patients with BPAD23 also reached a similar conclusion. Accordingly, it can be said that the findings on PAC are not generally influenced by the socio-demographic profile of the patients and the caregivers.

The present study suggested few associations of PAC with clinical variables. The SPACE domain of Self- esteem and social aspect of caring correlated positively with duration since in caregiver role, higher number of lifetime affective episodes, higher number of lifetime depressive episodes, and correlated negatively with age of onset. This suggests that caregivers of patients whose illness starts at a much earlier age, and who get involved with the patient in a caregiving role for a longer duration have more PAC. The caregiver esteem reflects the extent to which a caregiver feels confident about oneself while providing care to their ill relative. Accordingly, these associations suggest that the more severe longitudinal course of illness, especially the presence of more distressing symptoms over the years in the patients, is associated with a higher level of positive experience of caregivers in the form of self-esteem and social aspect of caring. This can possibly help the person to remain motivated in their caregiver role. Age of onset correlated negatively with total SPACE score and various SPACE domains except for Motivation for caregiving role, suggesting that caregivers of patients with a younger age of onset have a more positive caregiving experience.

There were few correlations between SPACE domains and total score with Hindi-IEQ domains which evaluate the subjective caregiving burden and FBIS which assesses both objective and subjective burden. There were positive correlations between SPACE and the Hindi-IEQ, whereas objective burden as assessed by FBIS were negatively correlated with SPACE. These findings suggest that an increase in subjective negative appraisal is associated with an increase in PAC, whereas an increase in objective burden is associated with lower PAC. A previous study of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia also suggested similar negative correlations between some of the domains of objective burden assessed by FBIS and a positive association between the Hindi-IEQ and SPACE.59 If one attempts to understand the subjective burden assessed by the Hindi-IEQ in the cognitive appraisal context, it can be considered an equivalent of negative caregiving appraisal. Accordingly, it can be said that the present study supports the existing literature based on use of the ECI among the caregivers of patients of schizophrenia23,60,62-65 and BPAD which suggested that those who experience a more positive caregiving experience also have a more negative caregiving appraisal.

In the present study, there was a positive correlation of SPACE domains of Caregiving personal gains, Caregiver satisfaction, and total SPACE score with Coercion as a coping mechanism, suggesting that higher use of coercion is associated with a higher positive caregiving experience. A previous study on the caregivers of schizophrenia showed similar associations of coercion as a coping mechanism and positive caregiving experience.58 Coercion is understood as ‘use of force to obtain compliance’ and in general is understood as a maladaptive coping mechanism. In the present study, the coercion item of the modified Hindi version of Coping Checklist stated that “if the patient indulges in something which you do not like, do you get annoyed / angry and shout at the patient so that the patient agrees to that thing”. In the context of caregiving for patients with BPAD, this may include the use of force on the part of the caregivers to control a highly violent patient or someone who is non-complaint to medications or other treatment advice. Coercion can also reflect over-controlling behaviour of caregivers which can reflect unexpressed emotions. If one understands coercion as a strategy to improve compliance of the patient with things which ultimately benefit the patient in terms of clinical and social outcome, the association of coercion and positive caregiving experience is understandable. However, if one interprets coercion only as a maladaptive coping mechanism, then this association is difficult to understand. It is important to note that in the present study, coercion as a coping mechanism was assessed by a single item. Hence, there is a need to assess coercion as a coping mechanism in more detail.

The SPACE domain of Self-esteem and social aspect of caring correlated negatively with Avoidance as a coping mechanism. This may suggest that higher use of avoidance leads to guilt and reduced self-esteem in caregivers.

The present study showed that better QOL of caregivers was associated with higher positive caregiving experience. This finding is similar to that of a previous study which used SPACE and the WHOQOL-BREF among the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia.58 Although the cause-outcome relationship cannot be drawn from this study, these findings support the view that enhancing the positive caregiving experience can improve the QOL of caregivers.

Our study also found no association between scores on SPACE and the GHQ-12. Previous studies based on ECI23,59 and SPACE58 among the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and BPAD also did not find any association between these measures.

The study had a number of limitations. It was limited to the caregivers of patients in remission and attending the outpatient services of a tertiary care hospital who were recruited by convenience sampling. Accordingly, the findings cannot be generalised to caregivers of patients with an acute episode of BPAD or who are admitted to an inpatient setting. The sample size of the study was small and we did not assess a number of other important aspects of caregiving such as social support, family structure, family environment, and caregivers’ expression of emotions. Future studies involving patients and caregivers from varied treatment settings can seek to overcome these limitations. The present study also included multiple variables and it is possible that some of the associations reported may represent type 1 errors.

Conclusion

This study suggests that positive caregiving experiences among the caregivers of patients with BPAD is similar to their counterparts of patients with schizophrenia. The positive caregiving experience is not influenced by the socio-demographic characteristics of patients or caregivers. Higher positive caregiving experience among the caregivers of patients with BPAD is associated with more severe longitudinal course of illness among the patients, lower objective burden, higher subjective negative caregiving appraisal, higher use of coercion and lower use of avoidance as coping mechanisms, and better QOL among caregivers. Interventions for caregivers of patients with BPAD could include improving their awareness of their own positive caregiving experiences as a potential means to support their continued positive engagement in their caregiver role.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM Jr, Baldessarini RJ, Strakowski SM, Stoll AL, et al. Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:220-8.

- MacQueen GM, Young LT. Bipolar II disorder: symptoms, course, and response to treatment. Psychiatry Serv 2001;52:358-61.

- Pope M, Dudley R, Scott J. Determinants of social functioning in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2007;9:38-44.

- Brodie HK, Leff MJ. Bipolar depression — a comparative study of patient characteristics. Am J Psychiatry 1971;127:1086-90.

- Kessler RC, Walters EE, Forthofer MS. The social consequences of psychiatric disorders, III: probability and marital stability. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:1092-6.

- Martínez-Arán A, Vieta E, Reinares M, Colom F, Torrent C, Sánchez- Moreno J, et al. Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:262-70.

- Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Harriss L. Suicide and attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:693-704.

- Simon GE. Social and economic burden of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:208-15.

- Merikangas KR, Mehta RL, Molnar BE, Walters EE, Swendsen JD, Aguilar-Gaziola S, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addict Behav 1998;23:893-907.

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1996;66:17-31.

- 1 Levin FR, Hennessy G. Bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Biol Psychiatry 2004;56:738-48.

- Fava GA. Subclinical symptoms in mood disorders: pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Psychol Med 1999;29:47-61.

- Michalak EE, Yatham LN, Lam RW. Quality of life in bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005;3:72.

- Huxley N, Baldessarini RJ. Disability and its treatment in bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disord 2007;9:183-96.

- Ellison N, Mason O, Scior K. Bipolar disorder and stigma: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord 2013;151:805-20.

- Chauvet-Gélinier JC, Gaubil I, Kaladjian A, Bonin B. Bipolar disorders and somatic comorbidities: a focus on metabolic syndrome, diabetes and cardiovascular disease [in French]. Encephale 2012;38 Suppl 4:S167-72.

- Miller C, Bauer MS. Excess mortality in bipolar disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014;16:499.

- Pompili M, Harnic D, Gonda X, Forte A, Dominici G, Innamorati M, et al. Impact of living with bipolar patients: Making sense of caregivers’ burden. World J Psychiatry 2014;4:1-12.

- Zendjidjian X, Richieri R, Adida M, Limousin S, Gaubert N, Parola N, et al. Quality of life among caregivers of individuals with affective disorders. J Affect Disord 2012;136:660-5.

- Reinares M, Vieta E, Colom F, Martínez-Arán A, Torrent C, Comes M, et al. What really matters to bipolar patients’ caregivers: sources of family burden. J Affect Disord 2006;94:157-63.

- Shamsaei F, Khan Kermanshahi SM, Vanaki Z, Holtforth MG. Family care giving in bipolar disorder: Experiences of stigma. Iran J Psychiatry 2013;8:188-94.

- Chakrabarti S, Raj L, Kulhara P, Avasthi A, Verma SK. Comparison of the extent and pattern of family burden in affective disorders and schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry 1995;37:105-12.

- Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Aggarwal M, Avasthi A, Kulhara P, Sharma S, et al. Comparative study of the experience of caregiving in bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2012;58:614- 22.

- Lloyd J, Patterson T, Muers J. The positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: A critical review of the qualitative literature. Dementia (London) 2016;15:1534-61.

- Lopez J, Lopez-Arrieta J, Crespo M. Factors associated with the positive impact of caring for elderly and dependent relatives. Arch Gerontol Geriatrics 2005;41:81-94.

- Bauer R, Spiessl H, Helmbrecht MJ. Burden, reward, and coping of adult offspring of patients with depression and bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord 2015;3:2.

- Szmukler GI, Burgess P, Hermann H, Benson A, Colusa S, Bloch S. Caring for relatives with serious mental illness: the development of the experience of caregiving inventory. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1996;31:137-48.

- Lawton MP, Moss M, Kleban MH, Gliskman A, Rovine M. A two- factor model of caregiving appraisal and psychological well-being. J Gerontol 1991;46:181-9.

- Pearlin LI. Caregiver’s stress and coping study (NIMHR01MH42122). San Francisco, CA: University of California, Human Development and Aging Programs; 1988.

- Farran CJ, Miller BH, Kaufman JE, Donner E, Fogg L. Finding meaning through caregiving: development of an instrument for family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychol 1999;55:1107-25.

- Tarlow BJ, Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Rubert M, Ory MG, Gallagher- Thompson D. Positive aspects of caregiving contributions of the REACH project to the development of new measures for Alzheimer’s caregiving. Res Aging 2004;26:429-53.

- Kate N, Grover S, Kulhara P, Nehra R. Scale for positive aspects of caregiving experience: development, reliability, and factor structure. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2012;22:62-9.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59 Suppl 20:22-33.

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967;6:278-96.

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978;133:429-35.

- Pai S, Kapur RL. The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: development of an interview schedule. Br J Psychiatry 1981;138:332- 5.

- Schene AH, van Wijngaarden B, Koeter MW. Family caregiving in schizophrenia: domains and distress. Schizophr Bull 1998;24:609-18.

- van Wijngaarden B, Schene AH, Koeter MW, Vázquez-Barquero JL, Knudsen HC, Lasalvia A, et al. Caregiving in schizophrenia: development, internal consistency and reliability of the Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire — European Version. EPSILON Study 4. European psychiatric services: Inputs linked to outcome domains and needs. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2000;39:S21-7.

- Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Ghormode D, Dutt A, Kate N, Kulhara P. An Indian adaptation of the Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire: similarities and differences in assessment of caregiver burden. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2011;21:142-51.

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976;33:766-71.

- Nehra R, Chakrabarti S, Sharma R, Kaur R. Psychometric properties of the Hindi version of the coping checklist of Scazufca and Kuipers. Ind J Clin Psychol 2002;29:79-84.

- Scazufca M, Kuipers E. Coping strategies in relatives of people with schizophrenia before and after psychiatric admission. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:154-8.

- Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med 1998;28:551-8.

- Saxena S, Chandiramani K, Bhargava R. WHOQOL-Hindi: a questionnaire for assessing quality of life in health care settings in India. World Health Organization Quality of Life. Natl Med J India 1998;11:160-5.

- Gautam S, Nijhawan M, Kamal P. Standardisation of Hindi version of Goldbergs General Health Questionnaire. Indian J Psychiatry 1987;29:63-6.

- Goldberg D. Detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire (Maudsley Monograph). Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1972.

- Cano A, Sprafkin RP, Scaturo DJ, Lantinga LJ, Fiese BH, Brand F. Mental health screening in primary care: a comparison of 3 brief measures of psychological distress. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001;3:206-10.

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple S, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990;30:583-94.

- Kramer BJ. Gain in the caregiving experience: Where are we? What next? Gerontologist 1997;37:218-32.

- Ribeiro O, Paúl C. Older male carers and the positive aspects of care. Ageing Soc 2008;28:165-83.

- Netto NR, Goh J, Yap P. Growing and gaining through caring for a loved one with dementia. Dementia 2009;8:245-61.

- Jervis LL, Boland ME, Fickenscher A. American Indian family caregivers’ experiences with helping elders. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2010;25:355-69.

- Peacock S, Forbes D, Markle-Reid M, Hawranik P, Morgan D, Jansen L, et al. The positive aspects of the caregiving journey with dementia: Using a strengths-based perspective to reveal opportunities. J Appl Gerontol 2009;29:640-59.

- Jansson W, Almberg B, Grafström M. A daughter is a daughter for the whole of her life: A study of daughters’ responsibility for parents with dementia. Health Care Later Life 1998;3:272-84.

- Sanders S. Is the glass half empty or full? Reflections on strain and gain in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Work Health Care 2005;40:57-73.

- Narayan S, Lewis M, Tornatore J, Hepburn K, Corcoran Perry S. Subjective responses to caregiving for a spouse with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs 2001;27:19-28.

- Murray J, Schneider J, Banerjee S, Mann A. Eurocare: A cross-national study of co-resident spouse carers for people with Alzheimer’s disease: II — A qualitative analysis of the experience of caregiving. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;14:662-7.

- Kate N, Grover S, Kulhara P, Nehra R. Positive aspects of caregiving and its correlates in caregivers of schizophrenia: a study from north India. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013;23:45-55.

- Grover S, Nehra R, Malhotra R, Kate N. Positive aspects of caregiving experience among caregivers of patients with dementia. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:71-8.

- Grover S, Bhadada S, Kate N, Sarkar S, Bhansali A, Avasthi A, et al. Coping and caregiving experience of parents of children and adolescents with type-1 diabetes: An exploratory study. Perspect Clin Res 2016;7:32-9.

- Aggarwal M, Avasthi A, Kumar S, Grover S. Experience of caregiving in schizophrenia: a study from India. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2011;57:224- 36.

- Addington J, Coldham EL, Jones B, Ko T, Addington D. The first episode of psychosis: the experience of relatives. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003;108:285-9.

- Harvey K, Burns T, Fahy T, Manley C, Tattan T. Relatives of patients with severe psychotic illness: factors that influence appraisal of caregiving and psychological distress. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001;36:456-61.

- Lau DY, Pang AH. Caregiving experience for Chinese caregivers of persons suffering from severe mental disorders. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2007;17:75-80.