East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2019;29:129-35 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1811

SPECIAL COMMUNICATION

Daniel Poremski, BSc, MSc, PhD, Institute of Mental Health, Buangkok Green Medical Park, Singapore

Elayne Loo, RN, Institute of Mental Health, Buangkok Green Medical Park, Singapore

Christopher Yi Wen Chan, MBBS, MMed (Psychiatry), Institute of Mental Health, Buangkok Green Medical Park, Singapore

Liu Dong Li, RN, Institute of Mental Health, Buangkok Green Medical Park, Singapore

Daniel Fung, MMed, Institute of Mental Health, Buangkok Green Medical Park, Singapore

Address for correspondence: Dr Daniel Poremski, Institute of Mental Health, Buangkok Green Medical Park, 10 Buangkok View, Singapore, 539747.

Email: Daniel_poremski@imh.com.sg

Submitted: 2 May 2018; Accepted: 21 August 2018

Abstract

Objective: The application of restraints during psychiatric crises is a serious adverse event. We aimed to reduce the number of injuries sustained by patients during the application of restraints.

Methods: Structured interviews were conducted with 10 staff to determine six root causes of patient injury during restraint. Three plan-do-study-act cycles were implemented: (1) reorganising shift rosters to pair trained staff with inexperienced staff, (2) holding monthly session for practising de-escalation and restraint techniques as a team in a supervised setting, and (3) rotating the responsibility for leading the de-escalation in real crises.

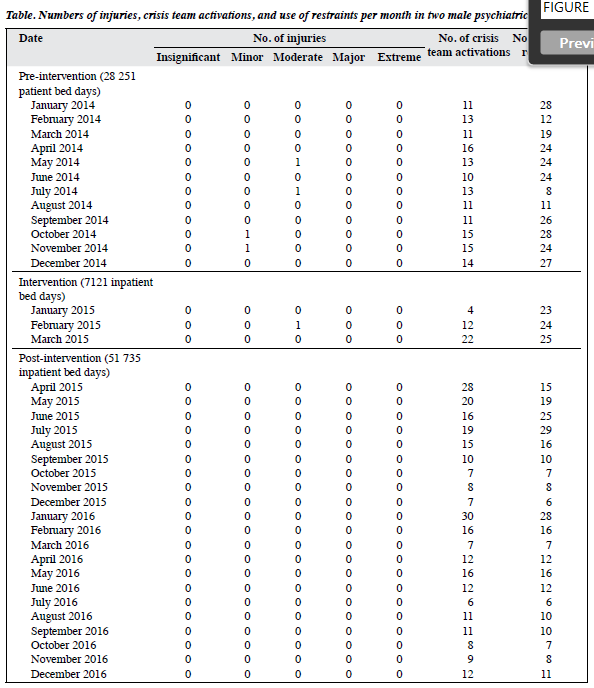

Results: Pre-intervention period was from January 2014 to December 2014 (28 251 inpatient bed days). Intervention period was from January 2015 to March 2015 (7121 inpatient bed days). Post-intervention period was from April 2015 to December 2016 (51 735 inpatient bed days). Data extracted included the dates and numbers of crises, activation of the crisis team, use of restraints, and injuries. During pre-intervention and intervention periods, only two minor and three moderate injuries were recorded. During post-intervention period, no injury was recorded and the number of restraints decreased gradually although the number of crisis team activations increased in the early phase. Eventually restraints were used only upon arrival of the crisis team.

Conclusion: Our quality improvement project identified six root causes and implemented three plan-do- study-act cycles to successfully eliminated patient injuries during the use of restraints.

Key words: Quality improvement; Restraint, physical; Wounds and injuries

Introduction

Injuries while receiving necessary medical care can occur during delivery of any services.1-3 In general medical settings, serious adverse events may occur in 14% to 21% of service users2,4; most such events are deemed preventable. The patterns and causes of adverse events are similar in Asian hospitals and not specific to any healthcare model.5 In mental health inpatient settings, estimates of adverse events are less accessible.6 Most studies on adverse events relate to medication interactions, dosage errors, and adverse drug reactions.7,8 However, adverse events also include physical injuries during treatment (such as falls) and during the use of restraints.9-15 Most injuries are sustained during the course of restraining aggressive or agitated patients by both service users and providers.10 The staff injury rate in mental health inpatient settings remains high.6,16

Guidelines have been established to reduce the risk of staff injury arising from patient contact,6,17 and indirectly reduce the use of restraints and seclusion and patient complaints.18-21 Nonetheless, few studies investigate the impacts of restraint on patient health and the experience of the restraint process.22,23

Alternatives to the use of restraints have been implemented with varying success,14,24 but are insufficient to improve quality of care.25 Such alternatives include staff education, advanced patient consultation for preferences on managing aggressive behaviour,26,27 improvement of ward environment to increase productive stimulation,25 and the use of rapid intramuscular tranquilisers.27,28

Previous quality improvement projects such as reorganisation of behavioural health crisis programmes only incidentally addressed issues of injuries during crises.23 The Lean methods could reduce the occurrence of staff injury, but patient injury was not directly addressed.23

In 2014 at the Institute of Mental Health, Singapore, 153 crises (11 to 12 per month) were documented in two male psychiatric wards with a capacity of 43 beds each. We implemented a quality improvement

project to reduce the number of patient injuries during the use of restraints.

Methods

This quality improvement project followed the World Health Organization guidelines for quality improvement.29

The study was approved by the Clinical Practice Improvement Programme review committee of the Institute of Mental Health, Singapore (Project number 08062014). The project aimed to provide clinical solutions through a structured approach by asking quality improvement questions, determining the problems, identifying the causes, isolating the root causes, developing strategies and interventions to address the root causes, evaluating the effect of interventions, and applying interventions that are effective.30 The project has been used in mental health wards to reduce violence and restraints.21,31

The Institute of Mental Health is the main source of psychiatric care in Singapore. It has 2000 inpatient beds in 50 wards and receives approximately 16 000 visits in a year.32 The cost of care is heavily subsidised through means- tested financial assistance programmes.33

The quality improvement team is led by a nurse practitioner and comprises nurses, medical residents, a former patient with lived experience of being injured during the use of restraints, and security support staff.

The use of restraints is governed by a protocol that outlines the acceptable and unacceptable reasons for the use of restraints. Physical restraint is the last resort when all alternatives are ineffective or unsuitable. The protocol requires staff to explain to patients being restrained the reason for restraint and the criteria for release. For vulnerable patients with surgical illnesses or acute injuries, extra precautions are required.

Care and response training is provided monthly for health attendants and allied health workers and twice a month for nurses. Recertification is required every second year. New ward staff are required to complete crisis management courses, including verbal de-escalation techniques and management of agitated individuals. However, some staff may have begun working prior to completing the courses. The intensity of training differs among staff types; for example, registered nurses require advanced training and administrative staff require basic courses only. Awareness of certain techniques may differ among staff.

If de-escalation techniques do not resolve a crisis and the patient remains at high risk, the crisis team will be called and staff will intervene. If immediate intervention is required owing to risks to the patient or those around, staff may intervene before the crisis team arrives. Once the patient is restrained, staff must check and review the patient’s behaviour hourly to determine if he is ready for release. The decision to release depends on behavioural assessment when the patient has been calm for the past 1 hour.

Identifying causes

The quality improvement team conducted structured interviews with 10 staff to determine the causes and situations leading to injuries and to construct a cause- and-effect diagram. The team then voted to select six root causes:

(1) Poor team coordination: a lack of communication resulted in too many staff assisting in holding down the patient. Without a clear set of roles, staff was unsure about who led the de-escalation, as the role of communicating with the patient shifts in crisis, confusing the patient.

(2) Patient resistance: the patient felt threatened by the crowd and struggled and could not focus on the de-escalation messages or comply with orders because explanations were unclear. In addition, patients resisted when staff ignored their requests.

(3) Labour shortage: staff had regular duties and were under time pressure to resolve crises. This led to limited use of de-escalation techniques and the use shortcuts.

(4) Poor crisis team response time: staff may be overconfident to attempt restraint prior to receiving proper support and hence at increased risk of injury.

(5) Improper application of restraint techniques: staff was under time constraints and skipped vital steps during restraint to ensure patient safety.

(6) Poor appraisal of the crisis: staff believed the patient in crisis was beyond de-escalation. Inexperienced staff may have resorted to brief de-escalation or restraint prior to attempting de-escalation. Lack of understanding of the psychiatric condition also contributed to ineffective de-escalation negotiation. Adrenergic responses with high levels of arousal and fear affected staff judgment and appraisal of the situation, leading to application of force greater than necessary.

The six root causes were plotted on a Pareto chart and were ranked based on the number of votes. The Pareto principle was adapted to show how 80% of the issues may come from 20% of identified causes.34 The Pareto chart identified three root causes that contributed the most to the injuries, and three plan-do-study-act cycles were developed in line with quality improvement project guidelines.29,35

Intervention

The three plan-do-study-act cycles were implemented from January to March 2015. The first cycle related to role uncertainty during the crisis (poor team coordination). Staff skill level in handling crises was unevenly distributed; therefore, shift rosters were reorganised to distribute trained staff equally. Talks were held to remind staff of the techniques and procedures of crisis management and highlight underlying rationales. Getting all staff to attend the talks was challenging given the variability of rosters and schedules. Extending the talks to weekends allowed greater attendance.

The second cycle related to practice of control and restraint techniques (improper application of restraint techniques). Monthly sessions were conducted under supervision of at least two instructors for practising de- escalation, break-away, and restraint techniques and for discussing recent incidents. Attendance was monitored. Staff were debriefed at the end of every session for areas of improvement.

The third cycle related to practice of de-escalation techniques (poor appraisal of the crisis). Staff took turns to lead de-escalation in genuine situations. Immediate debriefing by the supervisor provided feedback on areas of improvement and strengthened staff self- confidence.

Results

Data from two male psychiatric wards were reviewed through the Incident Reporting Information System. Pre- intervention period was from January 2014 to December 2014 (28 251 inpatient bed days). Intervention period was from January 2015 to March 2015 (7121 inpatient bed days). Post-intervention period was from April 2015 to December 2016 (51 735 inpatient bed days). Data extracted included the dates and numbers of crises, activation of the crisis team, use of restraints, and injuries (Table).

Injury severity was determined using the Severity Assessment Categorization as insignificant (no injury, no increased level of care or length of stay), minor (increased level of care), moderate (permanent lessening of physical function), major (major permanent loss of function), or extreme (death). Adverse events secondary to administration of sedatives were not included in analysis.

The mean patient age was 41 years. The distribution of illnesses was comparable between patients in the two wards and patients in the hospital, with predominance of psychotic disorders, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders.32 The distribution of ethnicity was comparable between patients in the two wards and the Singapore population, with predominance of Chinese, followed by Indian and Malay.

During pre-intervention and intervention periods, only two minor and three moderate injuries were recorded; the frequency was too low to determine the impact of interventions.36 During post-intervention period, no injury was recorded and the number of restraints decreased gradually although the number of crisis team activations increased in the early phase. Eventually restraints were used only upon arrival of the crisis team. This was due to change in staff understanding of ‘risk of immediate harm’. Prior to training, staff had a lower threshold of what behaviours constituted immediate risk. After training, staff had greater tolerance for behaviours that previously considered immediate risk. This enabled more time for de-escalation and for the crisis team to arrive.

Sustainability

To maintain sustainable outcome, we increased staff capacity to practise the care and response techniques and selected staff to receive additional training and act as training session leaders. In addition, we developed new algorithms with the use of rapid tranquilisers and debriefing steps to reduce the use of restraints and increase patient choice and self-directed care. Furthermore, patients were included in the committees that oversee the training, and peer support services were more generally integrated, as reported in other Asian settings.37

Discussion

The quality improvement project successfully minimised the number of patient injuries during the use of restraint. We identified six root causes of injuries (poor team coordination, patient resistance, labour shortage, poor crisis team response time, improper application of restraint techniques, and poor appraisal of the crisis) and implemented three plan-do-study-act cycles: (1) reorganising shift rosters to pair trained staff with inexperienced staff, (2) holding monthly session for practising de-escalation and restraint techniques as a team in a supervised setting, and (3) rotating the responsibility for leading the de-escalation in real crises. Immediate feedbacks were given. These strategies echo previous quality improvement interventions to reduce violence31 and injuries from restraints.21,23,38 Staff learned to work together to avoid role confusion. Staff were trained across ranks and titles both horizontally and vertically.21,23

Continued training programmes can reduce the occurrence of injuries,23 duration of restraint, and the use of seclusion measures for aggressive patients.27,39,40 Such team training may also increase staff confidence and team cohesion and reduce staff injury.18,19,27 In addition, it may be beneficial to include caregivers in training to help them cope with difficult situations at home. If de-escalation techniques are standardised among staff, patients may receive consistent cues about when to refocus their aggression, and caregivers may be better prepared to deal with aggressive behaviours outside hospital.41

Staff may receive conflicting messages about reduced use of coercive techniques (for better patient-centred care) and stricter enforcement of rules (for patient safety).42,43

There may be a paradox in application of restraints and training of staff. Staff may rarely use restraints because of low confidence and experience. Increased staff confidence and training may undesirably increase the application of restraints and thereby reduce patient satisfaction and adherence to trauma-informed practice. However, increased confidence empowers staff to apply non-physical de- escalation techniques and lead to fewer injuries during restraint. The physical restraint protocol and crisis management algorithm highlight the importance of de- escalation (Figure). Although trauma informed care was not explicitly used in training, it highlighted the importance of staff empowerment in transforming nursing culture consistent with trauma informed care.12,27,42 Inputs from patients are essential.44,45 Understanding patient experience should be the core of training.25,44 Inclusion of a former patient with lived experience of being injured during the use of restraints in our team highlighted a paradoxical situation: staff desire for faster response times may be at odds with patient preference for more time in verbal de-escalation. Experience with restraints may affect patient response to the potential threat of being restrained again. It is important to study the way patients are released from restraints46,47 and their preferences for de-escalation techniques.26

This study has several limitations. Although the number of injuries reduced during and after intervention, there was no control group for confounders. In May 2014, our hospital was successfully reaccredited. We focused only on two wards to maintain tight control of the procedures implemented to achieve accreditation. No additional steps were taken. Increased ward specialisation in 2015 and 2016 did not affect the two wards. The numbers of events and injuries were based on the institutional incident reporting system, which have been shown to document lower adverse event rates than other methods in studies of adverse drug reactions,8 including patient report.45 Nonetheless, we consider our data accurate, as the number of patient injuries was our primary outcome and reporting of injuries was not likely to be avoidable. Regarding analysis of structured interview data, we used established quality improvement methodologies29 rather than qualitative analytic techniques.48

Although the composition of our acute male wards resembles other settings,32 generalisation of our findings to mixed wards may not be appropriate. The zero-inflated nature of the data precludes the reliable use of inferential statistics to determine the impact of our strategies.

Conclusion

Our quality improvement project identified six root causes and implemented three plan-do-study-act cycles to successfully eliminated patient injuries during the use of restraints.

Acknowledgements

The quality improvement team would like to thank staff who responded to our interviews, project facilitator Samsuri Bin Buang, Dr Gervais Wan Sai Cheong, Dr Alex Su Hsin Chuan, Seah Xiang Bing, and Catherine Chua Siew Hong. We would especially like to thank the former patient with lived experience of being injured during the use of restraints for contributing to our project. Without their assistance, the quality improvement project would not have been possible.

Declaration

The authors have no competing financial or personal interests.

References

- James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf 2013;9:122-8. Crossref

- Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2124-34. Crossref

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press; 2000.

- Classen DC, Resar R, Griffin F, Federico F, Frankel T, Kimmel N, et al. ‘Global trigger tool’ shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:581-9. Crossref

- Hwang JI, Kim J, Park JW. Adverse events in Korean traditional medicine hospitals: a retrospective medical record review. J Patient Saf 2018;14:157-63. Crossref

- Hankin CS, Bronstone A, Koran LM. Agitation in the inpatient psychiatric setting: a review of clinical presentation, burden, and treatment. J Psychiatr Pract 2011;17:170-85. Crossref

- Eriksson R, Werge T, Jensen LJ, Brunak S. Dose-specific adverse drug reaction identification in electronic patient records: temporal data mining in an inpatient psychiatric population. Drug Saf 2014;37:237-47. Crossref

- Maidment ID, Lelliott P, Paton C. Medication errors in mental healthcare: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:409-

- Crossref

- Aizenberg D, Sigler M, Weizman A, Barak Y. Anticholinergic burden and the risk of falls among elderly psychiatric inpatients: a 4-year case- control study. Int Psychogeriatr 2002;14:307-10. Crossref

- Bonner G, Lowe T, Rawcliffe D, Wellman N. Trauma for all: a pilot study of the subjective experience of physical restraint for mental health inpatients and staff in the UK. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2002;9:465-73. Crossref

- 1 Jacob T, Sahu G, Frankel V, Homel P, Berman B, McAfee S. Patterns of restraint utilization in a community hospital’s psychiatric inpatient units. Psychiatr Q 2016;87:31-48. Crossref

- Perkins E, Prosser H, Riley D, Whittington R. Physical restraint in a therapeutic setting; a necessary evil? Int J Law Psychiatry 2012;35:43-

- Crossref

- Steinert T, Lepping P, Bernhardsgrutter R, Conca A, Hatling T, Janssen W, et al. Incidence of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric hospitals: a literature review and survey of international trends. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:889-97. Crossref

- Beghi M, Peroni F, Gabola P, Rossetti A, Cornaggia CM. Prevalence and risk factors for the use of restraint in psychiatry: a systematic review. Riv Psichiatr 2013;48:10-22. Crossref

- Wu WW. Psychosocial correlates of patients being physically restrained within the first 7 days in an acute psychiatric admission ward: retrospective case record review. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:47-57.

- McCue RE, Urcuyo L, Lilu Y, Tobias T, Chambers MJ. Reducing restraint use in a public psychiatric inpatient service. J Behav Health Serv Res 2004;31:217-24. Crossref

- Marder SR. A review of agitation in mental illness: treatment guidelines and current therapies. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(Suppl 10):13-21. Crossref

- Short R, Sherman ME, Raia J, Bumgardner C, Chambers A, Lofton V. Safety guidelines for injury-free management of psychiatric inpatients in precrisis and crisis situations. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:1376-8. Crossref

- Allen DE. Staying safe: re-examining workplace violence in acute psychiatric settings. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2013;51:37-

- Crossref

- Smith GM, Ashbridge DM, Altenor A, Steinmetz W, Davis RH, Mader P, et al. Relationship between seclusion and restraint reduction and assaults in Pennsylvania’s forensic services centers: 2001-2010. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:1326-32. Crossref

- Bell A, Gallacher N. Succeeding in sustained reduction in the use of restraint using the improvement model. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2016;5. pii: u211050.w4430. Crossref

- Ling S, Cleverley K, Perivolaris A. Understanding mental health service user experiences of restraint through debriefing: a qualitative analysis. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60:386-92. Crossref

- Wale JB, Belkin GS, Moon R. Reducing the use of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric emergency and adult inpatient services: improving patient-centered care. Perm J 2011;15:57-62. Crossref

- Taxis JC. Ethics and praxis: alternative strategies to physical restraint and seclusion in a psychiatric setting. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2002;23:157-70. Crossref

- Gagnon MP, Desmartis M, Dipankui MT, Gagnon J, St-Pierre M. Alternatives to seclusion and restraint in psychiatry and in long-term care facilities for the elderly: perspectives of service users and family members. Patient 2013;6:269-80. Crossref

- Hellerstein DJ, Staub AB, Lequesne E. Decreasing the use of restraint and seclusion among psychiatric inpatients. J Psychiatr Pract 2007;13:308-17. Crossref

- Sullivan AM, Bezmen J, Barron CT, Rivera J, Curley-Casey L, Marino D. Reducing restraints: alternatives to restraints on an inpatient psychiatric service--utilizing safe and effective methods to evaluate and treat the violent patient. Psychiatr Q 2005;76:51-65. Crossref

- Huang CL, Hwang TJ, Chen YH, Huang GH, Hsieh MH, Chen HH, et al. Intramuscular olanzapine versus intramuscular haloperidol plus lorazepam for the treatment of acute schizophrenia with agitation: an open-label, randomized controlled trial. J Formos Med Assoc 2015;114:438-45. Crossref

- World Health Organization. Quality Improvement in Primary Health Care: a Practical Guide. 2004.

- Wilson RM, Harrison BT. What is clinical practice improvement? Intern Med J 2002;32:460-4. Crossref

- Brown J, Fawzi W, McCarthy C, Stevenson C, Kwesi S, Joyce M, et al. Safer wards: reducing violence on older people’s mental health wards.

BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2015;4.pii: u207447.w2977. Crossref

- Poremski D, Kunjithapatham G, Koh D, Lim XY, Alexander M, Lee C. Lost keys: understanding service providers’ impressions of frequent visitors to psychiatric emergency services in Singapore. Psychiatr Serv 2017;68:390-5. Crossref

- Ministry of Health. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/ moh_web/home/costs_and_financing/schemes_subsidies/Medifund. html. Accessed 4 November 2015.

- Sanders R. The Pareto principle: its use and abuse. J Serv Mark 1987;1:37-40. Crossref

- Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:290-8. Crossref

- Bradburn MJ, Deeks JJ, Berlin JA, Russell Localio A. Much ado about nothing: a comparison of the performance of meta-analytical methods with rare events. Stat Med 2007;26:53-77. Crossref

- Chang TC, Liu JS. Beyond illness and treatment. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2014;24:125-7.

- Okin RL. Variation among state hospitals in use of seclusion and restraint. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1985;36:648-52. Crossref

- Kontio R, Pitkanen A, Joffe G, Katajisto J, Valimaki M. eLearning course may shorten the duration of mechanical restraint among psychiatric inpatients: a cluster-randomized trial. Nord J Psychiatry 2014;68:443-9. Crossref

- Huckshorn KA. Reducing seclusion and restraint use in inpatient settings: a phenomenological study of state psychiatric hospital leader and staff experiences. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2014;52:40-

- Crossref

- Madathumkovilakath NB, Kizhakkeppattu S, Thekekunnath S, Kazhungil F. Coping strategies of caregivers towards aggressive behaviors of persons with severe mental illness. Asian J Psychiatr 2018;35:29-33. Crossref

- Isobel S, Edwards C. Using trauma informed care as a nursing model of care in an acute inpatient mental health unit: a practice development process. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2017;26:88-94. Crossref

- Johansen ML. Conflicting priorities: emergency nurses perceived disconnect between patient satisfaction and the delivery of quality

patient care. J Emerg Nurs 2014;40:13-9. Crossref

- Allen MH, Carpenter D, Sheets JL, Miccio S, Ross R. What do consumers say they want and need during a psychiatric emergency? J Psychiatr Pract 2003;9:39-58. Crossref

- Weingart SN, Pagovich O, Sands DZ, Li JM, Aronson MD, Davis RB, et al. What can hospitalized patients tell us about adverse events? Learning from patient-reported incidents. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:830-6. Crossref

- Riley D, Meehan C, Whittington R, Lancaster GA, Lane S. Patient restraint positions in a psychiatric inpatient service. Nurs Times 2006;102:42-5.

- Goulet MH, Larue C, Lemieux AJ. A pilot study of “post-seclusion and/or restraint review” intervention with patients and staff in a mental health setting. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2018;54:212-20. Crossref

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res

Psychol 2006;3:77-101. Crossref