East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2025;35:3-10 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2513

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Tsz Ying Yeung, Mimi MC Wong

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the relationships among loneliness, maladaptive coping, and depressive symptoms in Chinese older patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), and to compare differences in loneliness and coping between Chinese older individuals with and without depression.

Methods: Chinese patients aged ≥60 years who were diagnosed with MDD were approached in a randomised sequence during follow-up appointments at psychiatric outpatient clinics. Attendees of general outpatient clinics and elderly community centres matched for age, sex, and education level were recruited by convenience sampling as controls. Both groups completed a questionnaire that included the six-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, the Brief Coping Orientation to Problem Experiences Inventory, the Social Readjustment Rating Scale, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, the Hong Kong version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric, and the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale. Hierarchical multiple linear regression was performed to examine relationships among coping, loneliness, and depressive symptoms, followed by correlation and mediation analyses.

Results: In total, 100 cases and 100 matched controls were included in the analysis. Cases reported significantly greater overall, emotional, and social loneliness relative to controls. Among patients with MDD, emotional loneliness and avoidant coping were associated with depressive symptoms. Among controls, only emotional loneliness was associated with depressive symptoms. Among all participants, avoidant coping partially mediated the relationship between emotional loneliness and depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were positively correlated with overall, emotional, and social loneliness, and avoidant coping and negatively correlated with problem-focused coping.

Conclusion: Loneliness and coping should be considered in comprehensive clinical assessments, psychiatric formulations, and individualised treatment plans for older patients with MDD. Targeted interventions addressing emotional loneliness and maladaptive coping strategies are warranted in MDD management.

Key words: Aged; Case-control studies; Coping skills; Depression; Loneliness; Mediation analysis

Tsz Ying Yeung, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Mimi MC Wong, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Address for correspondence: Dr Tsz Ying Yeung, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: janetyeung2323@hotmail.com

Submitted: 7 February 2025; Accepted: 3 March 2025

Major depressive disorder (MDD) affects approximately 13% of older adults.1 In this population, MDD often follows a chronic, remitting course; it is strongly associated with functional impairment, persistent disability, and increased risks of relapse and recurrence.2 The risks of non-suicide and suicide-related mortality are also elevated.3 Antidepressants elicit a response in only 40% to 50% of patients;4 thus, psychosocial interventions are crucial for individuals who are inadequately treated by pharmacological methods alone.

Loneliness, emotional or social, is a distressing subjective experience that arises from the discrepancy between desired interpersonal relationships and perceived current connections.5 Many older adults experience loneliness due to changing life circumstances such as widowhood, medical conditions, and difficulties adjusting to retirement.6 The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated loneliness and mental health issues in older adults.7 High levels of emigration may lead to empty nest syndrome among older people in Hong Kong.8 Loneliness is positively associated with depressive symptoms in older adults,9-11 as well as their risk factors such as advanced age, female sex, marital dissatisfaction, limited social engagement, medical comorbidities, and functional impairments.2,12 Loneliness is also associated with adverse physical and psychological outcomes including poorer physical health, increased morbidity and mortality, cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s disease progression,13 and suicide.14 Loneliness and depression may have a synergistic negative impact on quality of life.14

Coping refers to the cognitive and behavioural efforts used to manage external and internal demands arising from stressful challenges or threats to one’s goals or well-being.15 Coping is a complex process that may be problem-focused (actions to change or eliminate stressors) or emotion- focused (regulation of emotional responses to stressors).15 The latter is further classified into adaptive coping and maladaptive coping (ie, psychological disengagement and avoidance).16 Maladaptive coping is a psychological risk factor for MDD in older adults.17-19 Older adults with low levels of avoidant coping and high levels of problem-focused coping demonstrate fewer depressive symptoms in both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies.20 Problem-focused coping is associated with lower levels of loneliness, whereas emotion-focused coping is associated with higher levels of loneliness.21 The association between maladaptive coping and loneliness supports the use of cognitive behavioural therapy, which may improve social skills, enhance social support, and increase opportunities for social contact.22

Previous studies on the mediating role of maladaptive coping in loneliness and depressive symptoms have primarily focused on younger populations,23 despite differences in coping styles across age groups.24 Other studies examining relationships between loneliness and depression are limited by cultural differences or by the inclusion of non-clinical participants with milder depressive symptoms.25-28 This study aimed to investigate relationships among loneliness, maladaptive coping, and depressive symptoms in Chinese older patients with MDD, and to compare differences in loneliness and coping between Chinese older individuals with and without depression.

This case-control study was conducted between 1 August 2022 and 28 February 2023. Chinese patients aged ≥60 years who were diagnosed with MDD (based on the DSM-IV Axis I, Patient version29), could read and speak Chinese, and attended three public psychiatric outpatient clinics in the Kowloon East Cluster, Hong Kong, were approached in a randomised sequence during follow-up appointments until the target sample size was reached. Patients were excluded if they had any lifetime or current DSM-IV diagnosis other than MDD, a score of ≤19 on the Hong Kong version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK- MoCA), alcohol or substance dependence, unstable medical illness (eg, metastatic cancer, brain tumour, or other cardiac, hepatic, or renal conditions requiring hospital admission), or were mentally unfit to provide consent. Attendees of general outpatient clinics and elderly community centres matched for age, sex, and education level were recruited by convenience sampling as controls. Controls were excluded if they had any lifetime or current DSM-IV diagnosis, a score >7 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), a past or active history of any psychiatric illness, or a score of ≤19 on the HK-MoCA.

Both groups completed a questionnaire that included the six-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, the Brief Coping Orientation to Problem Experiences (COPE) Inventory, the Social Readjustment Rating Scale, the HAM-D, the HK-MoCA, the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric, and the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale. The interview process lasted approximately 1 to 2 hours for each participant.

Sample size calculation indicated that 100 participants were required per group. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Windows version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). All tests were two-tailed, and a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Case and control groups were compared using the independent t test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the Chi- squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Confounding factors associated with depressive symptoms were determined using univariable analysis; variables with a p value of <0.1 were included in multivariable analysis. Multicollinearity was considered non-significant if the variance inflation factor was <5. Hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses were performed to examine relationships among variables and depressive symptoms while adjusting for confounding factors. Coefficients of determination (R2) and standardised regression coefficients (β) were reported; the F-test was used to evaluate differences between two variances. Correlations between scores of the HAM-D, De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, and Brief COPE Inventory were analysed using Pearson’s correlation or Spearman’s rho correlation. Cohen’s criteria for correlation effect sizes were applied (small = 0.10, moderate = 0.30, large = 0.50).30 Mediation analysis was conducted to assess the mediating effect of coping in the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms using Hayes’ PROCESS macro for mediation analysis.31 Bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was performed to obtain parameter estimates for indirect effects. A mediation effect was considered statistically significant if the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval did not include zero.

In total, 5674 patients aged ≥60 years diagnosed with MDD attended psychiatric clinics in the Kowloon East Cluster during the recruitment period. Of the 184 patients approached, 53 declined to participate due to time constraints (n = 41), lack of interest (n = 10), or illiteracy (n = 2), whereas 131 (71.2%) agreed to participate. Of these 131 patients, 11 were excluded due to alcohol dependence (n = 1), a score of ≤19 on the HK-MoCA (n = 5), a revised diagnosis to bipolar disorder (n = 1), mood disorder (n = 1), or adjustment disorder (n = 3); 20 more were excluded during the age and sex matching process. Of the 145 controls approached, 34 declined to participate due to privacy concerns (n = 16), time constraints (n = 11), lack of interest (n = 5), or illiteracy (n = 2), whereas 111 (76.6%) agreed to participate. Of these 111 controls, 11 were excluded due to alcohol dependence (n = 1), a history of psychiatric illness (n = 3), a score of ≤19 on the HK-MoCA (n = 5), or a score of >7 on the HAM-D (n = 2). Therefore, 100 cases and 100 matched controls were included in the analysis.

The case and control groups were comparable in terms of baseline characteristics, except for marital status (divorced/separated: 19.0% vs 6.0%; married: 56.0% vs 63.0%; p = 0.028), recipient of Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (20.0% vs 10.0%, p = 0.048), participation in social organisations (47.0% vs 74.0%, p < 0.001), and a family history of depression (33.0% vs 11.0%, p < 0.001).

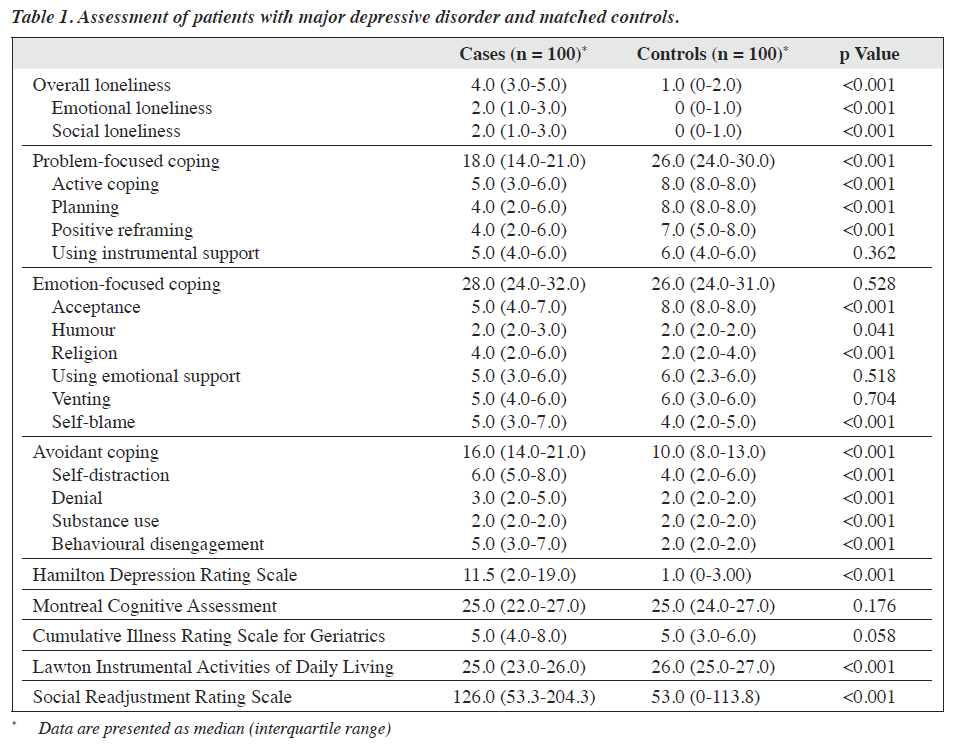

Cases had higher median scores than controls for overall, emotional, and social loneliness, as well as avoidant coping including self-distraction, denial, and behavioural disengagement (all p < 0.001), whereas controls had higher median scores for problem-focused coping including active coping, planning, and positive reframing (all p < 0.001) [Table 1]. The two groups were comparable in terms of emotion-focused coping, but cases had higher median scores on the subscales of religion and self-blame (p < 0.001), whereas controls had a higher median score for acceptance (p < 0.001). Additionally, cases had a higher median HAM-D score (11.5 vs 1.0, p < 0.001), a lower median Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living score (25.0 vs 26.0, p < 0.001), and a higher median Social Readjustment Rating Scale score (126.0 vs 53.0, p < 0.001).

Among patients with MDD, the mean age at onset was 58.4 years; 52.0% experienced onset at age ≥60 years; 26.0% had a history of psychiatric admission; and 12.0% had a history of suicide attempts. Overall, 41.0% had a single depressive episode and 59.0% had recurrent episodes. The numbers of depressive episodes were zero in 41.0%, one in 26.0%, and ≥2 in 33.0%. The median duration of the current episode was 6 months in 48 actively depressed patients (HAM-D >7).

Regarding treatment, 70.0% of patients were receiving medication only, 4.0% were receiving psychotherapy only, 24.0% were receiving both medication and psychotherapy, and 2.0% were receiving neither medication nor psychotherapy. Antidepressants were prescribed to 97.0% of patients, and 28.0% had a history of receiving psychotherapy.

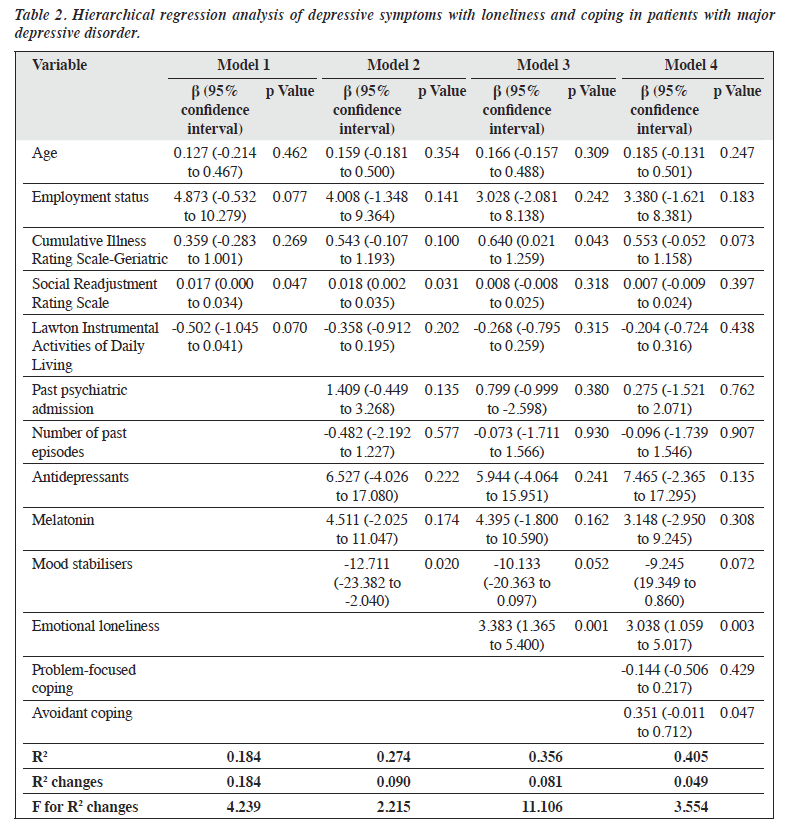

Among patients with MDD, HAM-D scores were associated with age, employment status, physical comorbidities, functional ability, stressful life events, past psychiatric admission, number of past episodes, and current use of antidepressants, mood stabilisers, and melatonin. Among controls, HAM-D scores were associated with employment status and stressful life events. These confounding factors were adjusted during multivariate analysis.

In hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis, the inclusion of emotional loneliness significantly increased the proportion of explained variance in depressive symptoms (R2 change = 0.081, F for R2 change = 11.106), as did the addition of coping subscales (R2 change = 0.049, F for R2 change = 3.554) [Table 2]. Among cases, depressive symptoms were associated with emotional loneliness (β = 3.038, p = 0.003) and avoidant coping (β = 0.351, p = 0.047). The overall model demonstrated a good fit (R2 = 0.405), indicating that the predictors collectively explained 40.5% of the variance in depressive symptoms. Among controls, depressive symptoms were associated with emotional loneliness (β = 0.470, p = 0.025) and stressful life events (β = 0.006, p = 0.031). The overall model yielded an R2 value of 0.125, indicating that the predictors collectively explained 12.5% of the variance in depressive symptoms.

Among all participants, depressive symptoms were positively correlated with overall loneliness (r = 0.582, p < 0.001), emotional loneliness (r = 0.608, p < 0.001), social loneliness (r = 0.407, p < 0.001), and avoidant coping strategies (r = 0.478, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with problem-focused coping strategies (r = -0.515, p < 0.001) [Table 3]. Problem-focused coping was positively correlated with emotion-focused coping (r = 0.291, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with avoidant coping (r = -0.548, p < 0.001), overall loneliness (r = -0.586, p < 0.001), emotional loneliness (r = -0.480, p < 0.001), and social loneliness (r = -0.513, p < 0.001).

Mediation analysis indicated a significant indirect effect (parameter estimate = 0.154; standard error = 0.042, 95% confidence interval = 0.079-0.242) of emotional loneliness on depressive symptoms through avoidant coping. Both the direct effect of emotional loneliness on depressive symptoms and the total effect (direct and indirect effects) were significant (Figure).

Among older patients with MDD, emotional loneliness and avoidant coping were associated with depressive symptoms, even after adjustment for confounding factors. Although emotional loneliness was associated with depressive symptoms in controls, no association was observed between coping and depressive symptoms. Among all participants, depressive symptoms were positively correlated with overall loneliness, emotional loneliness, social loneliness, and avoidant coping and negatively correlated with problem-focused coping. Avoidant coping partially mediated the association between emotional loneliness and depressive symptoms. Significant differences in loneliness and coping were observed between patients with MDD and controls.

Only emotional loneliness, and not social loneliness, was significantly correlated with depressive symptoms in patients with MDD. Emotional loneliness refers to the absence of an intimate figure such as a partner or child, whereas social loneliness reflects deficits in a broader social network including friends or colleagues.5 This finding may be explained by the Confucian concept of filial piety. The perception of ‘one’s children are not filial’ is a risk factor for old-age loneliness in China, whereas Western societies place greater emphasis on autonomy and independence.32 The interdependence between parents and children, emphasised in Confucianism, involves the son reciprocating the nurture received in childhood by caring for his parents in old age, thereby completing the cycle of life. Consequently, Chinese older adults are more likely to rely on family members and less likely to seek emotional support from a broader social network. However, societal changes (eg, the shift to a nuclear family structure and altered intergenerational living arrangements) have reduced the frequency of contact and the availability of emotional support from children,33 a problem further exacerbated by emigration from Hong Kong.8 The unfulfilled generational expectations of filial piety intensify loneliness and worsen depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults. Although emotional loneliness was associated with depressive symptoms in controls, avoidant coping was not. Controls exhibited less avoidant coping and more problem-focused coping; the latter showed significant negative correlations with overall loneliness and social loneliness, which may provide protection against loneliness and depression.

Among all participants, avoidant coping partially mediated the association between emotional loneliness and depressive symptoms, which may explain the underlying mechanism. This finding aligns with the theory that lonely individuals tend to believe that they are powerless to change their predicament and perceive a lack of control over outcomes.14 This dysfunctional attribution style is associated with pessimism and low motivation;34 crucially, it escalates behavioural disengagement35 and sad passivity,34 ultimately leading to depression.

Patients with MDD exhibited significantly higher levels of overall, emotional, and social loneliness, and avoidant coping, as well as lower levels of problem-focused coping, compared with controls. Individuals with depression experience higher levels of overall loneliness and its subtypes, compared with individuals without depression.27 A meta-analysis revealed a 1.65-fold greater incidence of depression in lonely older adults, compared with non-lonely older adults.36

Patients with MDD were more likely to be divorced or separated. Relationships with close personal contacts or networks of relatives are strongly correlated with overall loneliness.37 For Chinese older adults, family serves as the primary source of social support, followed by friends. Married older adults with living spouses report lower levels of loneliness.38 Traditional Chinese culture emphasises family as the principal source of support. Although both divorce and widowhood can lead to loneliness for Chinese older adults, the termination of a marriage due to an untenable relationship is a more powerful trigger of loneliness than the death of a spouse.32 Additionally, a higher proportion of cases were recipients of Comprehensive Social Security Assistance. Low income is associated with loneliness in older adults39 because financial constraints can limit participation in social functions, impact self-esteem and self-efficacy, and ultimately reduce social contact.40

Observed differences in coping strategies between cases and controls are consistent with the results of previous studies.41,42 Avoidant coping subscale scores including self- distraction, denial, and behavioural disengagement were significantly higher in cases than in controls. This finding can be explained by the cognitive model of depression, in which individuals with depression hold negatively biased views of either the situation or their ability to deal with it. This negative bias fosters the use of avoidant coping, which offers only temporary relief.43 Conversely, problem-focused coping subscale scores including active coping, planning, and positive reframing were significantly higher in controls than in cases. Older adults who adopt problem-focused coping address stressors directly and attempt to implement constructive measures to modify or eliminate these stressful situations.44

Controls had a higher median score for acceptance, a type of emotion-focused coping in the Brief COPE Inventory. Although a longitudinal study in the Netherlands found a positive relationship between acceptance and depressive symptoms,45 this finding was interpreted within the framework of the learned helplessness model, in which depression is presumed to arise from the belief that control over outcomes is absent.46 However, acceptance is the opposite of denial; it involves accepting the reality of a situation without feeling helplessness.47 The concept of acceptance aligns with Chinese values that emphasise balance and integration. Individuals in Western cultures are more likely to adopt problem-solving strategies, whereas individuals in Asian cultures tend to adopt accommodation strategies in response to stressful environments.48,49 Confucianism and Taoism have influenced coping behaviours among Chinese individuals under stress. Confucianism emphasises forbearance, self-reflection, self-control, and the doctrine of the mean, whereas Taoism promotes a sense of non-being through the ‘take it easy’ or ‘let it be’ tenet.50 Additionally, Buddhism has a considerable influence on coping mechanisms among Chinese individuals; it emphasises the realisation of suffering (both internal and external distress), acceptance of life experiences, and achieving liberation from suffering by transforming craving and aversion through morality, meditation, and wisdom.51 The coping mechanism among Hong Kong individuals reflects a combination of fatalism (belief in external forces beyond human control) and activism (efforts to manage stressful encounters).52 Therefore, Chinese older adults might effectively cope with less controllable situations through acceptance.53

This study has multiple implications for clinical practice, public health, and future research. Psychological interventions targeting maladaptive coping should be offered to reduce depressive symptoms resulting from loneliness. Notably, only 28% of patients with MDD had a history of receiving psychotherapy, indicating possible under-treatment. Cognitive behavioural therapy can address recurrent cognitive biases within the loneliness model and foster adaptive cognitive and behavioural coping strategies to improve mood.43 Targeting maladaptive cognitions is a promising approach for reducing loneliness.22,54 Identification of risk factors and signs of loneliness in primary care settings is crucial for identifying older individuals at risk of developing depression. Policymakers can utilise technology to provide intervention and engagement platforms such as internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy, particularly for isolated individuals who are unable to attend in person.55

This study had several limitations. The cross-sectional design limited its ability to establish causal relationships, and the recruitment of cases from a single centre hindered generalisation of the findings to other populations. Further studies should be conducted with a more representative sample over an extended period. The sample size was insufficient to allow subgroup analysis. Although the HAM-D is commonly used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in older patients, it has not been specifically validated for the geriatric population.56 Self- rated instruments such as the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale and Brief COPE Inventory may be susceptible to reporting bias. The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms in older adults is consistent with findings from previous cross-sectional9-11 and longitudinal11,57-60 studies. The association between avoidant coping and depressive symptoms in patients with MDD is consistent with findings from a previous systematic review.20 However, the clinical significance of these results must be interpreted with caution. For example, the standardised regression coefficients indicated that one-point increases in emotional loneliness and avoidant coping corresponded to 3.038- and 0.351-point increases in the HAM-D score, respectively. Considering that a clinically meaningful change in the HAM-D score is 4 to 6 points,61 the significant correlation between emotional loneliness, avoidant coping, and depressive symptoms may not necessarily translate into a clinically meaningful change. Nonetheless, our study had several strengths including stringent inclusion criteria, age-, sex-, and education-matched controls, a high completion rate, and the use of valid and reliable psychometric tools.

Emotional loneliness and avoidant coping were associated with depressive symptoms in Chinese older patients with MDD. Avoidant coping partially mediated the association between emotional loneliness and depressive symptoms; higher levels of loneliness and avoidant coping were observed in patients with MDD relative to controls. Clinicians should incorporate screening for loneliness and maladaptive coping into comprehensive assessments that guide psychiatric management such as psychological interventions targeting maladaptive coping strategies.

Both authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Both authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Both authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Cluster of the Hospital Authority (reference: KC/KE-22-0116/ER-3). The participants provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

References

- Abdoli N, Salari N, Darvishi N, et al. The global prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) among the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2022;132:1067-73. Crossref

- Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003;58:249-65. Crossref

- Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry 2002;52:193-204. Crossref

- Kok RM, Nolen WA, Heeren TJ. Efficacy of treatment in older depressed patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of double- blind randomized controlled trials with antidepressants. J Affect Disord 2012;141:103-15. Crossref

- Weiss R. Loneliness: the Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation. MIT Press; 1975.

- Victor CR, Scambler SJ, Shah S, et al. Has loneliness amongst older people increased? An investigation into variations between cohorts. Ageing Society 2002;22:585-97. Crossref

- Kasar KS, Karaman E. Life in lockdown: Social isolation, loneliness and quality of life in the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Geriatr Nurs 2021;42:1222-9. Crossref

- Chan AKW, Cheung LTO, Chong EK, Lee MYK, Wong MYH. Hong Kong’s new wave of migration: socio-political factors of individuals’ intention to emigrate. Comp Migr Stud 2022;10:49. Crossref

- Adams KB, Sanders S, Auth EA. Loneliness and depression in independent living retirement communities: risk and resilience factors. Aging Ment Health 2004;8:475-85. Crossref

- Alpass FM, Neville S. Loneliness, health and depression in older males. Aging Ment Health 2003;7:212-6. Crossref

- 1 Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Ernst JM, et al. Loneliness within a nomological net: an evolutionary perspective. J Res Personality 2006;40:1054-85. Crossref

- Dahlberg L, McKee KJ, Frank A, Naseer M. A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging Ment Health 2022;26:225-49. Crossref

- Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:218-27. Crossref

- Heinrich LM, Gullone E. The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clin Psychol Rev 2006;26:695-718. Crossref

- Lazarus RS. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Vol 464: Springer; 1984.

- Scheier MF, Weintraub JK, Carver CS. Coping with stress: divergent strategies of optimists and pessimists. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1257-64. Crossref

- Arean PA, Reynolds CF 3rd. The impact of psychosocial factors on late-life depression. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:277-82. Crossref

- Aziz R, Steffens DC. What are the causes of late-life depression? Psychiatr Clin North Am 2013;36:497-516. Crossref

- Tang T, Jiang J, Tang X. Psychological risk and protective factors associated with depression among older adults in mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. Published online 11 October 2021. doi: 10.1002/gps.5637. Crossref

- Bjorklof GH, Engedal K, Selbaek G, Kouwenhoven SE, Helvik AS. Coping and depression in old age: a literature review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2013;35:121-54. Crossref

- Deckx L, van den Akker M, Buntinx F, van Driel M. A systematic literature review on the association between loneliness and coping strategies. Psychol Health Med 2018;23:899-916. Crossref

- Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2011;15:219-66. Crossref

- Vanhalst J, Luyckx K, Teppers E, Goossens L. Disentangling the longitudinal relation between loneliness and depressive symptoms: prospective effects and the intervening role of coping. J Soc Clin Psychol 2012;31:810-34. Crossref

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Pimley S, Novacek J. Age differences in stress and coping processes. Psychol Aging 1987;2:171-84. Crossref

- Chou KL, Chi I. Prevalence and correlates of depression in Chinese oldest-old. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:41-50. Crossref

- Liu T, Lu S, Leung DKY, et al. Adapting the UCLA 3-item loneliness scale for community-based depressive symptoms screening interview among older Chinese: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020;10(12):e041921. Crossref

- Raut NB, Singh S, Subramanyam AA, Pinto C, Kamath RM, Shanker S. Study of loneliness, depression and coping mechanisms in elderly. J Geriatr Ment Health 2014;1:20-7. Crossref

- She KH. A study of life events and psychological well-being among older persons in Hong Kong: the role of self-esteem, coping and locus of control. Master’s thesis. Lingnan University; 2004.

- So E, Kam I, Leung C, Chung D, Liu Z, Fong S. The Chinese bilingual SCID-I/P project: stage 1-reliability for mood disorders and schizophrenia. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry 2003;13:7-18.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155-9. Crossref

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: a Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications; 2017.

- Yang K, Victor CR. The prevalence of and risk factors for loneliness among older people in China. Ageing Soc 2008;28:305-27. Crossref

- Shi J. The evolvement of family intergenerational relationship in transition: mechanism, logic, and tension. J Chinese Sociol 2017;4:1-21. Crossref

- Smoyak SA. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 1984;22:40-1. Crossref

- Cacioppo JT, Ernst JM, Burleson MH, et al. Lonely traits and concomitant physiological processes: the MacArthur social neuroscience studies. Int J Psychophysiol 2000;35:143-54. Crossref

- Arifin MZ, Rohan HH. Meta-analysis the effects of loneliness on depression in elderly. Indonesian J Global Health Res 2023;5:335-44.

- Leung GT, de Jong Gierveld J, Lam LC. Validation of the Chinese translation of the 6-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale in elderly Chinese. Int Psychogeriatr 2008;20:1262-72. Crossref

- Chen Y, Hicks A, While AE. Loneliness and social support of older people in China: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community 2014;22:113-23. Crossref

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Hazan H, Lerman Y, Shalom V. Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: a review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. Int Psychogeriatr 2016;28:557-76. Crossref

- Fry PS, Debats DL. Self-efficacy beliefs as predictors of loneliness and psychological distress in older adults. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2002;55:233-69. Crossref

- Bjorklof GH, Engedal K, Selbaek G, Maia DB, Coutinho ES, Helvik AS. Locus of control and coping strategies in older persons with and without depression. Aging Ment Health 2016;20:831-9. Crossref

- Foster JM, Gallagher D. An exploratory study comparing depressed and nondepressed elders’ coping strategies. J Gerontol 1986;41:91-3. Crossref

- Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. Penguin; 1979.

- Saadati H, Froughan M, Azkhosh M, Bahmani B, Khanjani MS. Predicting depression among the elderly by stressful life events and coping strategies. J Family Med Prim Care 2021;10:4542-7. Crossref

- Kraaij V, Pruymboom E, Garnefski N. Cognitive coping and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a longitudinal study. Aging Ment Health 2002;6:275-81. Crossref

- Miller WR, Seligman ME. Depression and learned helplessness in man. J Abnorm Psychol 1975;84:228-38. Crossref

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;56:267-83. Crossref

- Lam AG, Zane NW. Ethnic differences in coping with interpersonal stressors: a test of self-construals as cultural mediators. J Cross Cult Psychol 2004;35:446-59. Crossref

- Tweed RG, White K, Lehman DR. Culture, stress, and coping: Internally-and externally-targeted control strategies of European Canadians, East Asian Canadians, and Japanese. J Cross Cult Psychol 2004;35:652-68. Crossref

- Yue X. Coping with Psychological Stresses Through Confucian Self- Cultivation and Taoist Self-Transcendence. Harvard University; 1993.

- Chen Y-H. Coping with suffering: the Buddhist perspective. In: Handbook of Multicultural Perspectives on Stress and Coping. Springer; 2006: 73-89. Crossref

- Lee RP. Social stress and coping behavior in Hong Kong. In: Chinese Culture and Mental Health. Elsevier; 1985:193-214. Crossref

- Cheng C, Cheung MW. Cognitive processes underlying coping flexibility: differentiation and integration. J Pers 2005;73:859-86. Crossref

- Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015;10:238-49. Crossref

- Khosravi P, Rezvani A, Wiewiora A. The impact of technology on older adults’ social isolation. Comput Human Behav 2016;63:594-603. Crossref

- Holroyd S, Clayton A. Measuring depression in the elderly: which scale is best. Medscape Gen Med 2000;2:430-54.

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging 2010;25:453-63. Crossref

- Heikkinen RL, Kauppinen M. Depressive symptoms in late life: a 10-year follow-up. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2004;38:239-50. Crossref

- Holvast F, Burger H, de Waal MM, van Marwijk HW, Comijs HC, Verhaak PF. Loneliness is associated with poor prognosis in late- life depression: Longitudinal analysis of the Netherlands study of depression in older persons. J Affect Disord 2015;185:1-7. Crossref

- Luo Y, Hawkley LC, Waite LJ, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:907-14. Crossref

- Rush AJ, South C, Jain S, et al. Clinically significant changes in the 17- and 6-item Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression: a STAR*D Report. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2021;17:2333-45. Crossref