East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2016;26:10-7

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Kok-Yoon Chee, MD, Department of Psychiatry & Mental Health, Kuala Lumpur Hospital, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

A/Prof. Adarsh Tripathi, MBBS, MD, Department of Psychiatry, King George’s Medical University, Chowk, Lucknow, India.

Prof. Ajit Avasthi, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, India.

Prof. Mian-Yoong Chong, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital-Kaohsiung Medical Center and School of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taiwan.

Dr Yu-Tao Xiang, MD, PhD, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macao, Macao SAR, PR China.

Dr Kang Sim, MD, Institute of Mental Health, Buangkok View, Buangkok Green Medical Park, Singapore.

Prof. Shigenobu Kanba, MD, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan.

Dr Yan-Ling He, MD, Department of Psychiatric Epidemiology, Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai, PR China.

Prof. Min-Soo Lee, MD, Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, Korea University, Seoul, South Korea.

Prof. Helen Fung-Kum Chiu, MD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, PR China.

Dr Shu-Yu Yang, PhD, Department of Pharmacy, Taipei City Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

Dr Hironori Kuga, MD, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan.

Prof. Pichet Udomratn, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand.

Prof. Andi Jayalangkara Tanra, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Dr Margarita Maria Maramis, MD, Dr Soetomo Hospital–Faculty of Medicine, Airlangga University, Jawa Timur, Indonesia.

Dr Sandeep Grover, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, India.

Dr Rathi Mahendran, MD, Department of Psychological Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore.

Prof. Roy A. Kallivayalil, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Pushpagiri Medical College, Thiruvalla, India.

Prof. Winston W. Shen, MD, Department of Psychiatry, TMU-Wan Fang Medical Center and School of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Prof. Naotaka Shinfuku, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan.

Dr Chay-Hoon Tan, MD, Department of Pharmacology, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

Prof. Norman Sartorius, MD, PhD, Association for the Improvement of Mental Health Programmes, Geneva, Switzerland.

Address for correspondence: Dr Chee Kok-Yoon, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Kuala Lumpur Hospital, Pahang Road, 50586 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Tel: (60-3) 2615 5770; Fax: (60-3) 2698 7394; Email: cheekokyoon@yahoo.com

Submitted: 16 July 2015; Accepted: 5 October 2015

Objective: Pharmacotherapy of depression in children and adolescents is complex. In the absence of research into the efficacy and safety of antidepressants in this group of patients, their off-label prescription is common. This paper aimed to illustrate the prescription pattern of antidepressants in children and adolescents from major psychiatric centres in Asia.

Methods: The Research on Asia Psychotropic Prescription Pattern on Antidepressants worked collaboratively in 2013 to study the prescription pattern of antidepressants in Asia using a unified research protocol and questionnaire. Forty psychiatric centres from 10 Asian countries / regions participated and 2321 antidepressant prescriptions were analysed.

Results: A total of 4.7% antidepressant prescriptions were for children and adolescents. Fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram were the most common antidepressants prescribed for children and adolescents. Almost one-third (30.3%) of prescriptions were for diagnoses other than depressive and anxiety disorders. There was less antidepressant polypharmacy and concomitant use of benzodiazepine, but more concomitant use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents compared with adults.

Conclusion: Off-label use of antidepressants in children and adolescents was reported by 40 Asian psychiatric institutions that participated in the study. In-service education and regulatory mechanisms should be reinforced to ensure efficacy and safety of antidepressants in children and adolescents.

Key words: Adolescent; Antidepressive agents; Child; Ethnopsychology

Antidepressant prescription in children and adolescents has gained significant attention in the last decade. Increased utilisation of psychotropic medication for treatment of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents has previously been comparable with use in adults.1 The issue of suicidality and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) first became a public concern when fluoxetine was reportedly associated with suicide in patients.2 Nonetheless, findings to the contrary have shown that SSRI may be associated with lower suicide rates in children and adolescents3 and the association with suicide may be invalid.4-6 As a result of the concerns, prescription of antidepressants to children and adolescents declined. There was a subsequent increase in the rate of completed suicides.7-9

Researchers from Europe, the US, and Taiwan have reported antidepressant prescription pattern in children and adolescents. A population-based study from Canada showed growth in the prevalence of antidepressant use among children and adolescents, largely due to an increase in SSRI use.10 A similar increasing trend of antidepressant prescription among children and adolescents was reported in Spain, Germany, Denmark, the UK, and the Netherlands.11-13 In the US, the rate of antidepressant use among children and adolescents also showed a rising trend.14,15 In Taiwan, the 1-year prevalence of antidepressant use in the paediatric population increased from 0.27% in 1997 to 0.47% in 2005.16

Data from Asia with regard to antidepressant prescription patterns are lacking. The Research on Asia Psychotropic Prescription Pattern on Antidepressants (REAP-AD) collaborated in 2013 to study the prescription pattern of antidepressants in Asia using a unified research protocol. Data on antidepressant prescription among children and adolescents (age ≤ 19 years) were extracted from the main database and analysed in order to understand the pattern of antidepressant use in this age-group.

Study Sample and Design

The study was part of the REAP project, an international, pharmaco-epidemiological study using a standardised data collection procedure in Asian countries / regions.17 The study sample comprised 2321 patients from 40 leading psychiatric centres in 10 Asian countries / regions (China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand).

A consensus meeting was held before the study to discuss methodological details, including uniformity of case selection, data collection, and data entry procedures to ensure comparability across sites and countries. Each centre used the same standardised protocol and data collection procedure. The survey was performed from March to June 2013. Information collected from the case records included age, gender, diagnosis, treatment setting, type of antidepressant(s) prescribed and concomitant psychotropics, as well as the dose prescribed by the psychiatrist. The treating psychiatrist completed the survey questionnaire. In this naturalistic study, patients were included if (i) they had been prescribed an antidepressant on the day of survey; (ii) a parent or guardian of the patient could comprehend the aims of the study; and (iii) a parent or guardian of the patient consented to participate in this study, and provided written or oral consent / assent according to the requirements of the clinical research ethics committee in the respective study centre. The clinical research ethics committee of the respective centres granted approval for the study protocol.

The survey settings included outpatient and inpatient facilities. Diagnoses were grouped under major standard ICD-10 categories: organic mental disorders (F0), mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F1), schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F2), mood disorders (F3), neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (anxiety-related conditions, F4), behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (F5), disorders of adult personality and behaviour (F6), mental retardation (F7), disorders of psychological development (F8), and behavioural and emotional disorders with onset in childhood and adolescence (F9). Children were defined collectively as age 5 to 9 years and adolescents as age 10 to 19 years based on the World Health Organization’s definition.18

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using the Wizard for Mac version 1.5. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality was used to ascertain the distribution of age. Comparison between categorical variables was performed using the Pearson Chi- square test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at 2-tailed p < 0.05.

Subject Demographics and Diagnoses

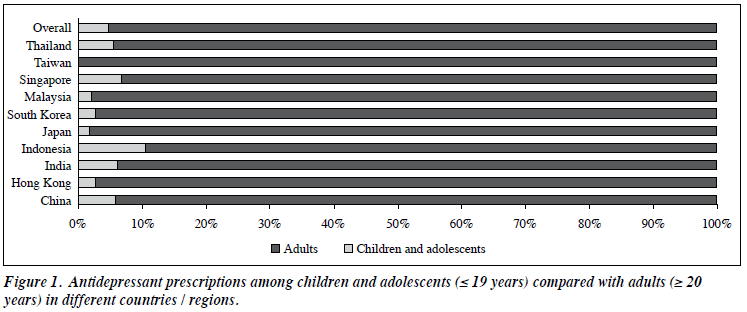

A total of 109 (4.7%) of the overall antidepressant prescriptions were for children and adolescents. None was reported from centres in Taiwan whilst most prescriptions for children and adolescents were from centres in Indonesia (Fig 1). Higher antidepressant prescription was reported with increasing age (Fig 2). Demographic data and diagnoses are presented in Table 1. The majority of antidepressant prescriptions were for an ICD-10 F3 diagnosis followed by that for an ICD-10 F4 diagnosis. Almost a third (30.3%) of antidepressant prescriptions were for diagnoses other than depression and anxiety: 12.8% of all prescriptions were for F2 diagnosis, 4.6% for F1 diagnosis, 0.9% for F5 diagnosis, 1.8% for F6 diagnosis, 2.8% for F7 diagnosis, 2.8% for F8 diagnosis, and 4.6% for F9 diagnosis. Compared with adults, there were more children and adolescents from the diagnostic categories F4 to F9 being prescribed antidepressants (Fig 2).

Among all patients prescribed antidepressants for schizophrenia and related disorders (i.e. F2 diagnosis), 90.9% had no co-morbidity in depression or anxiety disorders. In patients with F1, F2, or F5 to F9 diagnosis who was prescribed with antidepressant, 87.5% did not have co- morbidity in depression or anxiety.

Types of Antidepressant Prescribed

According to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical–Defined Daily Dose by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/), 62 medications are listed under the category of antidepressants, of which only 13 (21.0%) were prescribed in participating Asian centres. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were the most commonly prescribed antidepressant, among which fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram were prescribed the most. Of all antidepressants prescribed as monotherapy in this study population, 86.4% were on SSRI, 7.8% on tricyclic antidepressants, and 5.8% on serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (Table 2). Polypharmacy was rare and only found in 5.5% of the children and adolescents.

Comparisons between Children / Adolescents and Adults

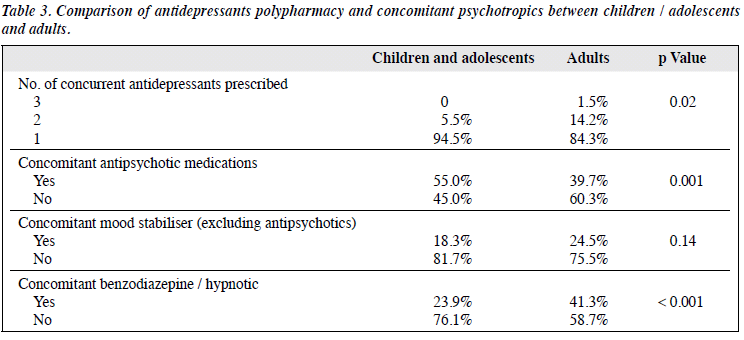

Comparison of antidepressant prescribing pattern between children / adolescents and adults < 65 years was performed (Table 3). Significantly more polypharmacy of antidepressants was found in adults: 15.7% of all adult prescriptions comprised ≥ 2 types of antidepressant compared with only 4.6% in children and adolescents. On the contrary, there was significantly more concomitant antipsychotic prescription in children and adolescents than adults (55.0% vs. 39.7%, p = 0.001). The most common antipsychotic medication prescribed in children and adolescents was risperidone (24.7%), most commonly for a mood disorder. There was lower concomitant use of benzodiazepine and hypnotic in children and adolescents compared with adults (23.9% vs. 41.3%, p < 0.001).

The present study is a collection of data about the prescribing pattern of antidepressants from 40 leading psychiatric centres in 10 Asian countries / regions. This study provides the demographic profiles and general trends of antidepressant use in these Asian countries / regions.

Overall, antidepressants are not recommended by some international practice guidelines as first-line treatment in children and adolescents with depressive disorders.19,20 No major difference was found between Asian and international treatment guidelines or between the Asian countries as the guidelines were adopted and adapted from western countries.21 Antidepressant use was considered off-label use because the manufacturer’s data sheets or product summary do not include indications that advocate antidepressant use in children or adolescents.22 Off-label use of psychotropic medication has been reported in many centres in Europe and the US. In the US, 62% of outpatient paediatric visits included off-label prescription23 and the majority of prescriptions was for SSRI.24 In a child and adolescent psychiatric department in Paris, France, 48% of prescriptions were off-label or unlicensed and 80% of those prescriptions were for antidepressants.25 In the UK, fluoxetine was the most common off-label antidepressant prescribed in general practice.26 In the Netherlands, off-label prescription of antidepressants in children was 1.1 per 1000 children in 2005, though a declining trend was reported due to the impact of a safety warning.27 Although our findings do not represent any individual country or territory, the percentage of off-label prescription of antidepressants in children and adolescents by the participating centres was demonstrated. Such off-label use of antidepressants in this age-group could partly be explained by the need for pharmacotherapy for children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders, especially major depressive disorder (MDD) and anxiety disorders. For example, although no antidepressant drug is approved by the UK Marketing Authorization for depression in children and young people (< 18 years), the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health issued a policy statement that permitted their use, despite being unlicensed in children and young people. Such use was considered necessary in the absence of any suitable alternative; in addition the balance of risks and benefits for such treatment was favourable. The issue of antidepressants being an off-label treatment for children and adolescents is likely due to the lack of information pertaining to the efficacy and safety aspects of antidepressants, in particular SSRI in children and adolescents. Medication use in this age-group should be evaluated. Clearly more research is required to focus on the efficacy and safety of antidepressants in children and adolescents in order to include such treatment as a standard management for those with MDD and anxiety disorders.

Polypharmacy in antidepressant prescription among children and adolescents is an underestimated phenomenon and the prevalence has increased in recent years.28 In our study, 5.5% of antidepressant polypharmacy was reported from the participating centres with significant percentages of benzodiazepine / hypnotic prescribed. The Finnish 1981 Nationwide Birth Cohort Study reported that the cumulative incidence of polypharmacy was 0.9% by the age of 20 years and concluded that such phenomenon often began in late adolescence.29 Analysis based on the South Carolina Medicaid programme in the US also showed a significantly rapid upward trajectory in the rate of polypharmacy in children and adolescents treated for depressive illness; the likelihood of polypharmacy increased with greater diagnostic complexity.30 Based on the current lack of evidence, polypharmacy is not recommended although in certain clinical situations where there is no single effective antidepressant to enable monotherapy, clinicians may resort to combination therapy with other classes of antidepressant. Nevertheless, benefits must be weighed against increased risk for adverse events such as serotonin syndrome and suicide among adolescents.31

Our study also found that antidepressants were prescribed in all the major psychiatric disorder categories of the ICD-10. Significant numbers of antidepressant prescription in schizophrenia have been reported by the REAP-AP (Research in East Asia Psychotropic Prescription Pattern on Antipsychotics) in hospitalised schizophrenic adult patients.32 Some have been explained by co- morbid depression or treatment for negative symptoms of schizophrenia but no similar research has been carried out in children and adolescents. Antidepressants have been suggested to be beneficial in the prodrome phase of schizophrenia in adolescents.33,34 Such a wide array of diagnoses associated with antidepressant prescription in children and adolescents also reflects the lack of understanding and research in the field of paediatric psychopharmacology.

Limitations

The major strength of this study is that it is a naturalistic study of antidepressant prescription patterns across countries / regions in Asia, albeit with different levels of income and sociocultural background. There are several limitations of this study. First, most of the research team members worked in hospitals or universities of major cities so data might not be generalised to rural areas and smaller cities. The findings from this survey were also not indicative of the practice in the countries of the participating centres. It is possible that in smaller hospitals or in rural areas with less financial support, far fewer second-generation antidepressants are used. Second, in view of the sampling frame and context, different patterns may emerge if more countries from within Asia are included in future studies. Third, future studies may look at greater homogeneity in sample sizes of the subjects, which are commensurate with each population, as well as examine other clinical factors (such as psychopathology scores, adverse events, quality of life) associated with such prescription patterns. Fourth, the sample size included in the analysis was small compared with the entire sample population of the REAP-AD study. Despite the small sample size, the results from this study provide an insight into the antidepressant prescription patterns in this group of people.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes greatly to the understanding of antidepressant use among children and adolescents in Asia. It adds to the knowledge regarding changing patterns of antidepressant use across Asia in the context of parallel changes in the West. This will hopefully encourage investigation of the causes of such changes and enhance efforts to optimise antidepressant use in the management of our patients.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest in writing this report. This study was supported in part by grants from the Taipei City Hospital (10201-62-077), Taipei, Taiwan. The authors are grateful to the following clinicians for their contribution to the REAP study.

China: Lan Cao, Yu-Ping Cao, Chao Chen, Yan-Ping Duan, Wei Hao, Qing-Li Fan, Qiang Feng, Li-Ling Jiang, Wen-Hui Jiang, Cai-Ping Liu, Xue-Rong Luo, Tao Li, Chen-Feng Ji, Wen-Hui Jiang, Yuan-Yuan Li, Hao-Jie Li, Qiong Liu, Kai-Ji Ni, Yi-Hua Peng, Mei-Hui Qiu, Tian-Mei Si, Dian- Hong Shi, Ning Su, Tao Tian, Qian Li, Guang-Ron Xie, Zhen-Kang Xue, Xiao-Ping Wang, Su-Lin Yan, Jie Yao, Fei-Yan Yin, Mei-Hong Yu, Jing-Ping Zhao, Min-Jie Zhu.

Hong Kong: CH Au, WT Chan, C Cheng, LK Cheung, PW Chung, MC Hong, R Ko, I Kam, Arthur Lam, Grace Leung, Gabor S Ungvari, W Tai, A Tsang, KH Tong, M Wong, Hoy-An Wong, C Wong.

India: Dipesh Bhagabati, Nilesh Shah.

Indonesia: Hervita Diatri, Elmeyda Effendy, Agung Frijanto, Shelly Iskandar, Isa Multazam Nur, Carla Marchira, Tini Sri P, Yuniar Sunarko.

Japan: T Arai, K Atake, M Akamatsu, N Eto, Senta Fujii, M Fuji, M Fujioka, H Fujita, Y Fujinaga, S Fukushima, J Fukuyama, Y Haraguchi, H Hori, M Hirano, S Inomata, C Iwagawa, A Ichimiy, T Kubo, K Kakeda, Sejima Kanako, N Kuwano, T Kawashima, D Katsuki, M Kawano, H Kamiya, H Kunitake, H Kodoma, K Kuroiwa, H Lida, J Maruo, S Miyashita, N Miyoshi, M Matsushita, T Miura, K Motomura, Y Nishimura, N Nakagawa, H Nagai, J Nakamura, S Nakanishi, Y Nakano, Y Nishizima, H Nawata, Uchida Naoki, K Ogomori, M Ogusu, Nishimura Ryoji, H Sanematsu, J Sato, T Shinkai, Shinji Shimodera, T Sunami, O Sakurai, S Sakaguchi, T Saitou, Y Suga, S Shimodera, Y Tomiyama, T Tsuchimoto, H Takei, H Tatebayshi, H Tateishi, T Yoshida, R Yoshimura, K Yamane, A Yabuki, K Yamada, M Yamama, T Yshimori.

Malaysia: Loi-Fei Chin, Loi-Khim Chin, Rahima Dahlan, Esther Gunaseli Ebenezer, Mohd Fadzli Mohammad Isa, Norhayati Nordin.

Singapore: Cornelia Chee, Cyrus Ho, Emily Ho, Roger Ho, Surej John, Ee-Heok Kua, Cecilia Kwok, Sandeep Raj Kala Naik, YM Lai, Donovan Lim, Adrian Loh, Yit-Shiang Lui, Vincent John Magat Lu, Jia-Yin Teng, Tina Tan, Wing-Foo Tsoi, Tung Tsoi, John Wong.

South Korea: Sang-Woo Hahn, Il-Lee Jong, Dae-Young Oh, Yong-Chon Park.

Taiwan: Tsung-Ming Hu, Hong-Bin Huang, Hsin-Nan Lee, Shih-Ku Lin, Tia-Se Su, Kuy-Lok Tan, Yi-Hsin Yang, Kuan-Pin Su.

Thailand: Sarosaporn Joowong, Nopporn Tantirangsee, Pitchayawadee Theeramokee, Chawit Tunvirachaisakul.

- Zito JM, Safer DJ, DosReis S, Gardner JF, Magder L, Soeken K, et al. Psychotropic practice patterns for youth: a 10-year perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003;157:17-25.

- Healy D, Aldred G. Antidepressant drug use & the risk of suicide. Int Rev Psychiatry 2005;17:163-72.

- Jureidini JN, Doecke CJ, Mansfield PR, Haby MM, Menkes DB, Tonkin AL. Efficacy and safety of antidepressants for children and adolescents. BMJ 2004;328:879-83.

- Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Solomon DH, Dormuth CR, Miller M, Mehta J, et al. Comparative safety of antidepressant agents for children and adolescents regarding suicidal acts. Pediatrics 2010;125:876-88.

- Phillips JA, Nugent CN. Antidepressant use and method of suicide in the United States: variation by age and sex, 1998-2007. Arch Suicide Res 2013;17:360-72.

- Miller M, Pate V, Swanson SA, Azrael D, White A, Stümer T. Antidepressant class, age, and the risk of deliberate self-harm: a propensity score matched cohort study of SSRI and SNRI users in the USA. CNS drugs 2014;28:79-88.

- Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Marcus SM, Bhaumik DK, Erkens JA, et al. Early evidence on the effects of regulators’ suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1356-63.

- Katz LY, Kozyrskyj AL, Prior HJ, Enns MW, Cox BJ, Sareen J. Effect of regulatory warnings on antidepressant prescription rates, use of health services and outcomes among children, adolescents and young adults. CMAJ 2008;178:1005-11.

- Guaiana G. Antidepressant prescribing and suicides in Emilia- Romagna region (Italy) from 1999 to 2008: an ecological study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health 2011;7:120-2.

- Meng X, D’Arcy C, Tempier R. Long-term trend in pediatric antidepressant use, 1983-2007: a population-based study. Can J Psychiatry 2014;59:89-97.

- Murray ML, de Vries CS, Wong IC. A drug utilisation study of antidepressants in children and adolescents using the General Practice Research Database. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:1098-102.

- Fegert JM, Kölch M, Zito JM, Glaeske G, Janhsen K. Antidepressant use in children and adolescents in Germany. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006;16:197-206.

- Abbing-Karahagopian V, Huerta C, Souverein PC, de Abajo F, Leufkens HG, Slattery J, et al. Antidepressant prescribing in five European countries: application of common definitions to assess the prevalence, clinical observations, and methodological implications. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014;70:849-57.

- Delate T, Gelenberg AJ, Simmons VA, Motheral BR. Trends in the use of antidepressants in a national sample of commercially insured pediatric patients, 1998 to 2002. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:387-91.

- Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:848-56.

- Chien IC, Hsu YC, Tan HK, Lin CH, Cheng SW, Chou YJ, et al. Trends, correlates, and disease patterns of antidepressant use among children and adolescents in Taiwan. J Child Neurol 2013;28:706-12.

- Shinfuku N. Research on Asian prescription patterns (REAP): focusing on data from Japan. Taiwan J Psychiatry 2014;28:71-84.

- World Health Organization adolescent development. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/en/ . Accessed 16 Sep 2015.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE clinical guideline: depression in children and young people. London: NICE; 2005.

- Birmaher B, Brent D; AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues, Bernet W, Bukstein O, Walter H, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:1503-26.

- Treuer T, Liu CY, Salazar G, Kongsakon R, Jia F, Habil H, et al. Use of antidepressants in the treatment of depression in Asia: guidelines, clinical evidence, and experience revisited. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2013;5:219-30.

- Neubert A, Wong IC, Bonifazi A, Catapano M, Felisi M, Baiardi P, et al. Defining off-label and unlicensed use of medicines for children: results of a Delphi survey. Pharmacol Res 2008;58:316-22.

- Bazzano AT, Mangione-Smith R, Schonlau M, Suttorp MJ, Brooke RH. Off-label prescribing to children in the United States outpatient setting. Acad Pediatr 2009;9:81-8.

- Lee E, Teschemaker AR, Johann-Liang R, Bazemore G, Yoon M, Shim KS, et al. Off-label prescribing patterns of antidepressants in children and adolescents. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:137-44.

- Serreau R, Le Heuzey MF, Gilbert A, Mouren MC, Jacqz-Aigrain E. Unlicensed and off-label use of psychotropic medications in French children: a prospective study. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther 2004;6:14- 9.

- Martin RM, Wilton LV, Mann RD, Steventon P, Hilton SR. Unlicensed and off label drug use for paediatric patients. General practitioners prescribe SSRIs to children off label. BMJ 1998;317:204.

- Volkers AC, Heerdink ER, van Dijk L. Antidepressant use and off- label prescribing in children and adolescents in Dutch general practice (2001-2005). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:1054-62.

- Díaz-Caneja CM, Espliego A, Parellada M, Arango C, Moreno C. Polypharmacy with antidepressants in children and adolescents. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014;17:1063-82.

- Gyllenberg D, Sourander A. Psychotropic drug and polypharmacy use among adolescents and young adults: findings from the Finnish 1981 Nationwide Birth Cohort Study. Nord J Psychiatry 2012;66:336-42.

- McIntyre RS, Jerrell JM. Polypharmacy in children and adolescents treated for major depressive disorder: a claims database study. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:240-6.

- Karow A, Lambert M. Polypharmacy in treatment with psychotropic drugs: the underestimated phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2003;16:713-8.

- Xiang YT, Ungvari GS, Wang CY, Si TM, Lee EH, Chiu HF, et al. Adjunctive antidepressant prescriptions for hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in Asia (2001-2009). Asia Pac Psychiatry 2013;5:E81-7.

- Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, Olsen R, Auther AM, Nakayama E, et al. Can antidepressants be used to treat the schizophrenia prodrome? Results of a prospective, naturalistic treatment study of adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:546-57.

- McGorry PD, Nelson B, Amminger GP, Bechdolf A, Francey SM, Berger G, et al. Intervention in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a review and future directions. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:1206-12.