East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2025;35:53-5 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2509

CASE REPORT

TK Adharshna, Preethy Kathiresan, Sanyam Tyagi, TK Abins, Pranshu Singh

TK Adharshna, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

Preethy Kathiresan, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

Sanyam Tyagi, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

TK Abins, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

Pranshu Singh, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

Address for correspondence: Dr TK Adharshna, PG Hostel, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

Email: adharshna.arsmi@gmail.com

Submitted: 26 January 2025; Accepted: 4 March 2025

Introduction

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a life- threatening condition with an incidence of 0.01% to 0.02% and a mortality rate of approximately 10%.1 It presents with high fever, muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and autonomic dysfunction. The risk of developing NMS is higher with potent neuroleptics, rapid dose escalation, and parenteral administration, particularly in young patients with structural or functional brain conditions who are vulnerable to polypharmacy.2 This report describes a case of NMS in a young man after misdiagnosis and intensive multidrug antipsychotic therapy.

Case presentation

In June 2022, a 22-year-old man presented to the emergency department of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, India, with a 6-day history of worsening symptoms including hand tremors, slowed movements, and neck stiffness, followed by high fever and reduced food and water intake. On day 3, the patient had become immobile and aggressive, exhibiting decreased interaction with his family. His symptoms escalated to frequent tremors, drooling, vomiting, and fixed gaze.

The patient had dropped out of school before ninth grade due to poor academic performance and was working as a cattle rearer. His family reported a 5-year history of provoked and unprovoked physical aggression, irritability, and disturbed sleep, all of which substantially impaired his social and occupational functioning. His symptoms were episodic, often triggered when family members entered his room or took his belongings. During these episodes, he did not explain his distress but responded with aggression— throwing utensils, breaking objects, or crying incessantly.

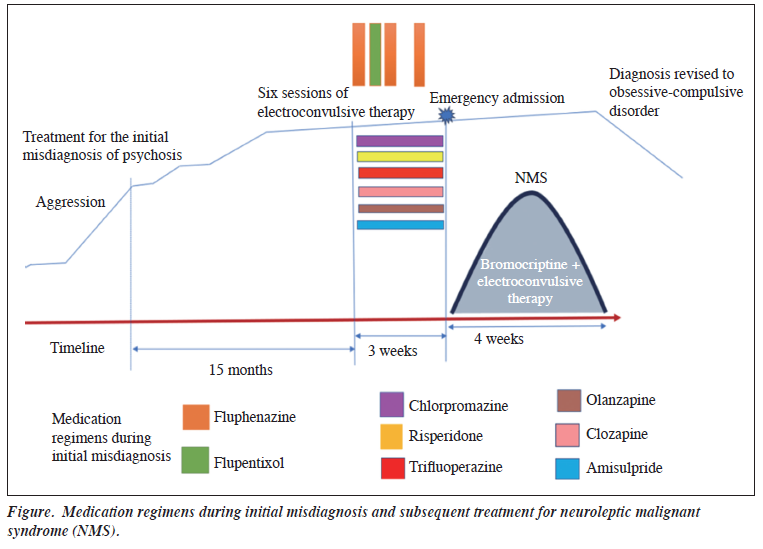

He had intermittent contact with psychiatric services for 15 months, although records were available only from the preceding month. A diagnosis of psychosis had been made based on aggressive behaviour, poor communication, and social withdrawal. No history of medical or other psychiatric illness was reported. Treatment had included high-dose antipsychotics: risperidone 3 mg three times daily, olanzapine 5 mg twice daily, trifluoperazine 5 mg/day, amisulpride 200 mg twice daily, and clozapine 150 mg/day, along with depot injections of fluphenazine (administered on 30 May, 12 June, and 18 June 2022) and flupentixol (administered on 18 June 2022) [Figure]. Additionally, six sessions of electroconvulsive therapy had been administered for aggression. These medications, given in high doses over 21 days, led to extrapyramidal symptoms.

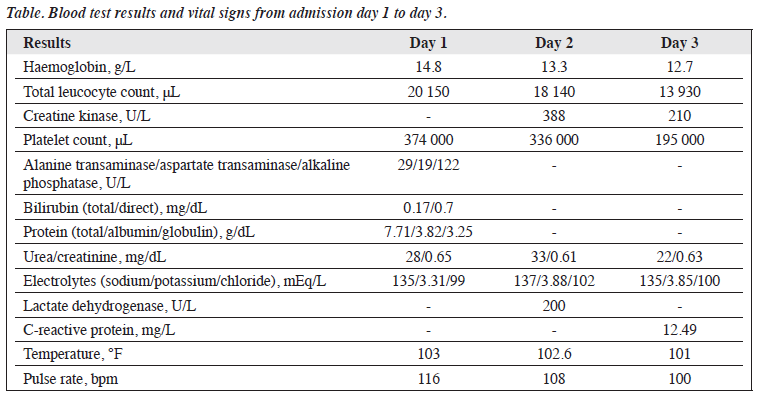

On examination, the patient exhibited rigidity, fixed gaze, and autonomic instability, along with high fever, excessive sweating, tachycardia, flushing, urinary incontinence, and drooling. Intubation was performed due to a declining Glasgow Coma Scale score. Blood test results showed elevated total leucocyte count and creatine kinase (Table).

Differential diagnoses included NMS, malignant catatonia, meningoencephalitis, septicaemia, malaria, and dengue. Computed tomography of the brain, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, blood and urine cultures, and dengue and malaria tests revealed unremarkable results, confirming the diagnosis of NMS according to DSM-5 criteria.

All psychiatric medications were discontinued; treatment with bromocriptine (2.5 mg three times daily) and lorazepam (2 mg twice daily) was initiated. Nevertheless, catalepsy, posturing, apathy, minimal speech, and occasional aggression persisted. Bromocriptine was titrated to 45 mg/day, and lorazepam was increased to 10 mg/day.

Electroconvulsive therapy was added to the patient’s regimen.2,3 He underwent 12 sessions, which led to clinically significant improvement of symptoms. Careful monitoring throughout treatment revealed a steady reduction in NMS symptoms, as measured by the NMS Rating Scale score,4 from 10 to 0 over 3 weeks. Muscle rigidity and tremors persisted after 2 weeks but gradually resolved. After 1 month, all blood test results had returned to normal levels; the patient recovered without residual symptoms.

A detailed interview and mental status examination revealed underlying obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight and borderline intellectual disability. Anger outbursts were triggered by anxiety-provoking thoughts related to symmetry and fear of contamination, which were elicited during the assessment. Fluoxetine was initiated and gradually increased to 40 mg/day; exposure and response prevention therapy was introduced. Follow-up assessments showed clinically significant improvement, with reductions in intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviours and a decrease in the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale score from 18 to 4.

Discussion

Our case illustrates the complexities of managing NMS in patients with psychiatric disorders, particularly in the context of misdiagnosis and inappropriate polypharmacy. The patient’s aggressive behaviour was likely related to anxiety from intrusive thoughts, compounded by borderline intellectual disability, which impaired his ability to understand his obsessions. Misdiagnosis may have been influenced by the presence of aggression, leading to insufficient evaluation during initial contact with mental health services. The patient’s borderline intelligence hindered articulation of his anger triggers, which were rooted in obsessive concerns about asymmetry and repetitive arranging behaviours. Family members were unable to identify these subtle behaviours; they found the aggression more distressing and repeatedly reported it to a doctor. Because of the patient’s limited insight into his illness, he expressed distress through crying or destructive behaviour, rather than verbalising discomfort. Poor academic performance and inadequate financial management skills, which are key indicators of borderline intellectual functioning, were overlooked during the initial assessment. This oversight may be attributed to cultural factors in rural India, where formal education is often undervalued, and children frequently enter the workforce early. Family assistance with most daily activities further masked the patient’s cognitive limitations. These findings highlight the need for thorough psychiatric evaluation beyond overt behavioural symptoms to prevent misdiagnosis.

A systematic review of NMS cases from 1965 to 2012 confirmed that antipsychotic drug combinations substantially increase NMS risk, emphasising the importance of rational prescribing practices.5 High-dose prescriptions, particularly those involving first-generation antipsychotics, have been implicated in many NMS cases.6 Considering the link between polypharmacy and NMS risk, psychiatrists must exercise caution when prescribing multiple high-dose antipsychotics, ensuring that regimens are justified by clinical necessity rather than empirical escalation. Pre- existing risk factors in our patient included young age, male sex, intellectual disability, probable dehydration, and high- dose polypharmacy. Prompt recognition and treatment of NMS are crucial to reducing mortality.

Our case highlights the importance of comprehensive history-taking, appropriate medication titration, and vigilant monitoring in NMS diagnosis and treatment. The integration of behavioural therapy along with pharmacotherapy played a critical role in managing obsessive-compulsive disorder, reinforcing the need for a multidisciplinary approach.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

References

- Wijdicks EFM. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2019.

- Berman BD. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a review for neurohospitalists. Neurohospitalist 2011;1:41-7. Crossref

- Strawn JR, Keck PE Jr, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:870-6. Crossref

- Sachdev PS. A rating scale for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatry Res 2005;135:249-56. Crossref

- Tse L, Barr AM, Scarapicchia V, Vila-Rodriguez F. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a review from a clinically oriented perspective. Curr Neuropharmacol 2015;13:395-406. Crossref

- Virolle J, Redon M, Montastruc F, et al. What clinical analysis of antipsychotic-induced catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome tells us about the links between these two syndromes: a systematic review. Schizophr Res 2023;262:184-200. Crossref