East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2020;30:20-7 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1852

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Ravindra N Munoli, MBBS, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

PSVN Sharma, DPM, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Sreejayan Kongasseri, MBBS, MD, North West area mental health services, Melbourne, Australia

Rajeshkrishna P Bhandary, MBBS, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Samir K Praharaj, DPM, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence: Dr Samir K Praharaj, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India, 576104.

Email: samirpsyche@yahoo.co.in

Submitted: 18 May 2018; Accepted: 23 November 2018 a distinct depressive class in terms of the strict binarian view (leaving the residual and heterogeneous group to be non- melancholic depressive class) and a more severe expression of depression in terms of the unitarian view.2

Abstract

Background: The binarian model views melancholia as a distinct depressive class, whereas the unitarian model views it as a more severe expression of depression. This study aims to investigate the sociodemographic, clinical, and course differences between melancholic and non-melancholic depression. Methods: This prospective observational study was carried out at Kasturba Hospital, Manipal, India from November 2010 to September 2011. We recruited consecutive inpatients aged 18 to 60 years who have a diagnosis of depressive disorder (based on ICD-10), with or without any psychiatric or physical comorbidities. Patients were categorised into melancholia and non-melancholia using the CORE questionnaire, with scores of ≥8 indicating the presence of melancholic depression. In addition, patients were evaluated using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, Somatoform Symptom Checklist, Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impression, and Presumptive Stressful Life Events Scale at baseline and at 1, 3, and 6 months.

Results: Of 87 inpatients with a diagnosis of depression, 50 met the inclusion criteria and 37 were excluded. Compared with patients with non-melancholic depression, patients with melancholic depression had higher depression score (30.8 vs 23.8, p < 0.001), had higher number of patients with psychotic depression (39.1% vs 7.4%, p = 0.007), had higher overall illness severity score (5.9 vs 4.8, p < 0.001), and had higher number of patients with suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour. Regarding the course of melancholia, the number of melancholic patients decreased from 23 at baseline to eight at 1 month, three at 3 months, and three at 6 months. Scores of non-interactiveness, retardation, and agitation decrease significantly over 3 months.

Conclusions: The construct and course of melancholia may be viewed as a part of depression, more in line with severe depression. Melancholia increases the risk for suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour.

Key words: Depressive disorder; Depressive disorder, major; Suicide

Introduction

Historically, depression has been described as melancholia, which comprised a cluster of symptoms such as dejection, sadness, despondency, anger, fear, delusions, and obsessions.1 In current psychiatry, melancholia is considered a distinct depressive class in terms of the strict binarian view (leaving the residual and heterogeneous group to be non- melancholic depressive class) and a more severe expression of depression in terms of the unitarian view.2

To accurately define melancholic depression, the CORE measure quantifies the degree of psychomotor disturbance, which is as an integral component of melancholia.3 Some psychiatrists consider melancholia is an entity with (1) distinctive set of clinical symptoms and signs, (2) genetically weighted, (3) primary biological determinants (compared with psychosocial determinants), (4) minimal placebo (psychotherapy) response rate, and (5) superior response to antidepressant drug therapy and electroconvulsive therapy.4

The role of psychosocial factors is considered less salient in melancholic depression than in non-melancholic depression.5 Melancholia has similar prevalence between sexes and is associated with older age of onset, slowed motor activity, and cognitive impairment such as perseverative responses and impaired attention, recall, and working memory. Motor impairments indicate fronto-striatal deficits, higher rates of non-suppression in the dexamethasone suppression test, and a blunted response to thyrotropin- releasing hormone. Compared with cognitive behaviour therapy, medication results in a significantly higher response in patients with higher CORE scores and with a diagnosis of melancholia. Furthermore, higher CORE scores predict a better response to electroconvulsive therapy.3

In inpatients and outpatients with depression, those with high CORE scores predict higher chances of being prescribed an antidepressant and a higher rate of improvement, compared with those with low CORE scores.2 The CORE measure may detect differential responses to antidepressants, as high CORE scores are associated with a higher recovery rate with fluoxetine than nortriptyline.6 In a study to determine optimal treatment for depression,7 melancholic and non-melancholic patients were randomised to sertraline, escitalopram, or venlafaxine extended-release treatment. At 8 weeks after treatment, remission or response was less likely to be achieved in melancholic than non- melancholic patients. Patients with melancholia remained lower on capacity for social skills. However, the poorer outcome was in part related to greater symptom severity at baseline.

This study aimed to compare melancholic depression with non-melancholic depression in terms of clinical features and course.

Methods

This prospective, observational study was carried out at Kasturba Hospital, Manipal, India from November 2010 to September 2011. Institutional ethics approval was obtained, as was written informed consent from each participant in the presence of a witness. We recruited consecutive inpatients aged 18 to 60 years who have a diagnosis of depressive disorder (based on ICD-10), with or without any psychiatric or physical comorbidities, and are able to read and write in English or Kannada language. Baseline characteristics of the sample has been published.8

Patients were assessed by a single psychiatrist at baseline and at 1, 3, and 6 months. Patients were excluded if the diagnosis was revised to bipolar disorder at follow up. No interference was performed during treatment.

The diagnosis of depression and the presence of any comorbid psychiatric disorders was confirmed using Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus.9 Personality disorder was first screened using the clinician-administered 8-items Standardized Assessment of Personality - Abbreviated Scale.10 Each item is scored either 0 or 1, and a total score of >3 indicates possible personality disorder, which was then confirmed using the Personality Disorder Questionnaire, 4th Revision.11 It is a 100-item, self- administered, true/false questionnaire that yields diagnoses consistent with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for the axis II disorders. Life events was assessed using the Presumptive Stressful Life Events Scale.12 It has 51 yes/no items and one additional ‘others’ item, which can be rated by clinician as lifetime events and events in past 1 year. It also generates scores for desirable, undesirable, and ambiguous events.

The severity of depression was assessed using the 21-item Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.13 Total scores range from 0 to 54 (for 17 items); score of <9 indicates no depression, 10-13 mild depression, 14-17 moderate depression, and ≥18 severe depression. Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the 14-item Structured Interview Guide for Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale.14 Total scores range from 0 to 56; score of <17 indicates mild anxiety, 18-24 mild-to-moderate anxiety, and 25-30 moderate-to-severe anxiety. Suicidality was assessed using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale.15 It comprises suicidal ideation, intensity of ideation, and suicidal behaviour. Somatoform symptoms associated with the depressive disorder were assessed using the Somatoform Symptoms Checklist.16 It was originally developed to arrive at ICD-10 diagnoses of somatoform disorders in the field trials. It uses yes/no questions to evaluate 60 somatic symptoms. Symptoms are considered present only in the absence of any physical cause. Overall illness severity was assessed using the 3-item Clinical Global Impression.17

The CORE Questionnaire2 was used to identify melancholia. It comprises 18 (observable) signs; each is rated on a four-point scale (0-3). Scores of ≥8 indicate the presence of melancholic depression. It has three subscales in a ‘trunk and branch’ model: a central non-interactiveness scale capturing cognitive impairment (6 items) and two motoric scales capturing retardation (7 items) and agitation (5 items).

Data were analysed using SPSS (Windows version 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago [IL], United States). The melancholic and non-melancholic depression groups were compared using the independent t test for continuous variables and Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Repeated measures ANOVA with Pillai’s Trace F was carried out to assess the change in CORE scores. Effect size was assessed using partial eta squared (η 2). The level of significance was kept at p<0.05 (2-tailed).

Results

Of 87 inpatients with a diagnosis of depression, 50 met the inclusion criteria and 37 were excluded because of being <18 years (n=3), >60 years (n=5), language difficulties (n=5), illiteracy (n=3), being from a distant place and unable to attend follow-up on schedule (n=14), refusal to give consent (n=2), no depression when evaluated using Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus (n=5). The diagnosis of two of the 50 patients included was changed to mania. 38 patients attended the 1-month and 3-month follow-up, and 18 patients completed the 6-month follow- up.

Melancholic and non-melancholic depression groups were comparable in terms of sociodemographic variables, except for monthly income (Table 1). Most patients in melancholic group had monthly income <$138, whereas most patients in non-melancholic group had monthly income >$138.

Compared with patients with non-melancholic depression, patients with melancholic depression had higher Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score (30.8 ± 4.9 vs 23.8 ± 4.4, p < 0.001), had higher number of patients with psychotic depression (39.1% vs 7.4%, p = 0.007), had a relative risk for psychotic depression of 5.3, and had higher overall illness severity score measured by Clinical Global Impression (5.9 ± 0.7 vs 4.8 ± 0.8, p < 0.001) [Table 2].

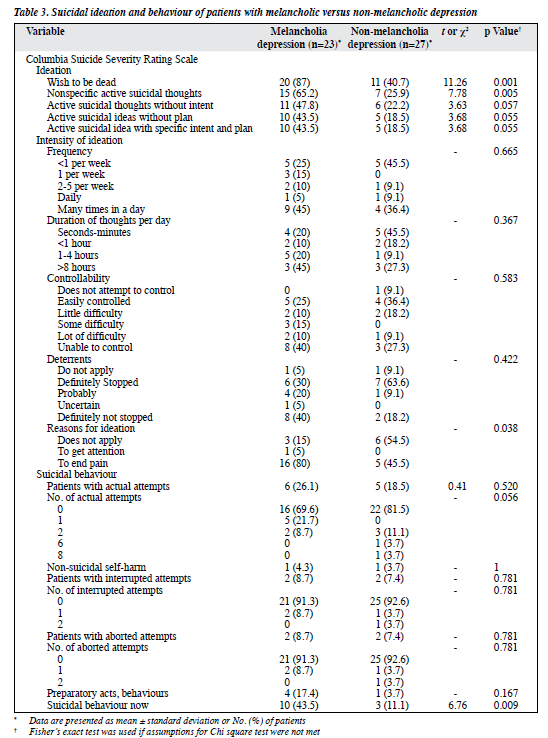

Compared with patients with non-melancholic depression, patients with melancholic depression had higher number of patients with suicidal ideation of ‘wish to be dead’ (p = 0.001) and non-specific active suicidal thoughts (p = 0.005), and higher number of patients with suicidal behaviour (p = 0.009) [Table 3].

Regarding the course of melancholia, the number of melancholic patients decreased from 23 at baseline to eight at 1 month, three at 3 months, and three at 6 months.

One patient who was not melancholic at baseline was melancholic at 6 months. As the attrition was high by 6 months, the CORE course was evaluated for 3 months. Scores of non-interactiveness, retardation, and agitation decrease significantly over 3 months, whereas scores of non- interactiveness and retardation decreased significantly more in the melancholic than non-melancholic group (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, the prevalence of melancholia was 46% among patients diagnosed with depression, which is higher than 3.5% to 12.8% in studies conducted in India18,19 and comparable to 25% to 44% in other studies.20,21 The higher rate of melancholic depression in our study is likely a reflection of severe cases seen in our tertiary care centre as opposed to community.

Melancholia has been associated with male sex and increasing age.3 Increase in CORE subscale and total scores with age was interpreted as a result of recruitment of more monoaminergic systems and higher prevalence of structural brain changes impacting on neural circuits relating to psycho-motor disturbance.22 Stressful life events were not associated with melancholia in our sample although one study reported inconsistent association with proximal and distal stressors.3 This supports the hypothesis that melancholia is more biologically determined, which is unaffected by the environmental factors including life events.

In the present study, all patients, except one, had severe depression (Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score of >18). Patients with melancholic depression were more severely depressed than those with non-melancholic depression, consistent to previous studies.23,24 These findings can be interpreted as (1) melancholia is an expression of severe depression and is in continuum with all depressive disorders; or (2) as half of severely depressed patients were non-melancholic, other factors could be contributing to melancholia, independent of severity of depression. Higher (but not significantly) anxiety score in melancholic patients indicates the role of anxiety in severe depression with melancholia. Patients with melancholic depression have higher rates of anxiety disorders.25,26

Patients with melancholic depression had higher rates of psychotic depression (relative risk = 5.3), consistent to a study that reported more psychotic episodes in melancholic patients than non-melancholic patients (relative risk = 2.9).24 Nonetheless, higher rates of psychotic symptoms in melancholic depression may represent distinctive ‘quality’ rather than just ‘quantitatively’ more severe depression.24

Furthermore, psychotic depression has been viewed as a subtype of melancholic depression, because of the shared phenotypic marker of psychomotor disturbance.24,27

In the present study, patients with melancholic depression had higher frequency of current suicidal behaviour and wish to be dead and non-specific active suicidal thoughts. The reason for suicidal ideation was mainly to end pain, indicating higher subjective suffering. In a study of suicide attempts in melancholic versus non- melancholic major depression, the former is associated with more serious past suicide attempts at baseline and higher probability of suicide attempt during follow-up, after controlling for depression severity and other covariates.28

In melancholia, suicide is associated with life events, personality, and substance use disorder.29 However, we did not find significant differences between groups in any of these parameters. A possible explanation for higher suicidal behaviour in melancholia is higher cognitive impairment, which suggests an anterior cingulate abnormality, which diminishes cognitive flexibility and influences decision- making.30 Clinically, it can be inferred that melancholia may be a precursor or marker of suicidal behaviour.

It has been argued that melancholic depression differs from non-melancholic depression quantitatively, not qualitatively.25 This is based on higher frequency of psychotic depression, anxiety, suicidality, and psychiatric comorbidity in melancholic depression, but none of these occur exclusively.31 Also, anhedonia, psychomotor retardation, and severe disturbances in vegetative functions predominate the clinical characteristics of melancholic depression.31 Furthermore, higher rates of early childhood adversity are found in melancholic depression. The hierarchical model theory argues that melancholic depression can be distinguished from non-melancholic depression based on clinical characteristics and involves perturbations in noradrenaline and dopamine in addition to serotonin.32,33

In our study, the course of melancholic and non- melancholic group was similar although treatment response was not examined. Studies have reported the extent to which CORE scores (whether dimensionalised or examined above and below cut-off) predict response to antidepressant medications. Antidepressants were superior to cognitive behaviour therapy in patients with melancholic depression and resulted in greater (not significantly) reduction in CORE scores (65% vs 35%).34 In a cross-sectional study of depressed out-patients, the mean CORE scores were significantly higher in the treatment-resistant group.35 In the Sequential Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression cohort, melancholic depression was associated with a significantly reduced rate of remission with citalopram.36 This was attributed to the overlap between melancholic symptoms and core depressive symptoms rated by the assessment instruments.36

Limitations of this study are the small sample size and high attrition rate during follow-up. Only literate inpatients were included, and all patients except one had severe depression. There was no representation from those with mild or moderate depression, thus limiting generalisation. Personality disorder was evaluated in two stages, but no diagnostic instrument was used to confirm the diagnosis. Nonetheless, the study design was naturalistic, and evaluation of depression was comprehensive to tap all changes during the course of illness, and CORE measure was used for evaluation of melancholia.

Conclusion

Melancholia may be considered as a severe form of depression with higher psychotic symptoms and suicidal ideation. Further research is required to understand the biological underpinnings of melancholia and the role of specific treatment methods and suicide prevention strategies.

Declaration

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. The paper was presented at the Annual National Conference of Indian Psychiatric Society 2018, Ranchi, India, on 6 February 2018.

References

- Radden J. Is this dame melancholy? Equating today’s depression and past melancholia. Philos Psychiatr Psychol 2003;10:37-52.

- Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. Development and Structure of the CORE System Melancholia: a Disorder of Movement and Mood: a Phenomenological and Neurobiological Review. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

- Parker G, McCraw S. The properties and utility of the CORE measure of melancholia. J Affect Disord 2017;207:128-35.

- Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. Melancholia: a Disorder of Movement and Mood. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

- Perry PJ. Pharmacotherapy for major depression with melancholic features: relative efficacy of tricyclic versus selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants. J Affect Disord 1996;39:1-6.

- Joyce PR, Mulder RT, Luty SE, McKenzie JM, Sullivan PF, Abbott RM, et al. Melancholia: definitions, risk factors, personality, neuroendocrine markers and differential antidepressant response. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2002;36:376-83.

- Day CV, John Rush A, Harris AW, Boyce PM, Rekshan W, Etkin A, et al. Impairment and distress patterns distinguishing the melancholic depression subtype: an iSPOT-D report. J Affect Disord 2015;174:493- 502.

- Munoli RN, Sharma PSVN, Kongasseri S, Bhandary RP, Praharaj SK. Clinical features and comorbidities of depression among inpatients in a tertiary care centre. Arch Ment Health 2014;15:193-200.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(Suppl 20):22-33.

- Moran P, Leese M, Lee T, Walters P, Thornicroft G, Mann A. Standardised Assessment of Personality - Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): preliminary validation of a brief screen for personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2003;183:228-32.

- Hyler SE. Personality Questionnaire, PDQ-4 +. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994.

- Singh G, Kaur D, Kaur H. Presumptive stressful life events scale (PSLES): a new stressful life events scale for use in India. Indian J Psychiatry 1984;26:107-14.

- Williams JB. A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:742-7.

- Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P, Endicott J, Lydiard B, Otto MW, et al. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A). Depress Anxiety 2001;13:166-78.

- Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1035-43.

- Janca A, Tacchini G, Isaac M. WHO International Study of Somatoform Disorders: an Overview of Methods and Preliminary Results. In: Ono Y, Janca A, Asai M, Sartorius N, editors. Somatoform Disorders. Keio University Symposia for Life Science and Medicine, Tokyo: Springer; 1999.

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, US: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976: 218-22.

- Teja JS, Narang RL. Pattern of incidence of depression in India. Indian J Psychiatry 1970;12,33-9.

- Bagadia VN, Jeste DV, Dave KP, Doshi SU, Shah LP. Depression: a study of demographic factors in 233 cases. Indian J Psychiatry 1973;15:209-16.

- Mulder RT, Joyce PR, Frampton CM, Luty SE, Sullivan PF. Six months of treatment for depression: outcome and predictors of the course of illness. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:95-100.

- Khan AY, Carrithers J, Preskorn SH, Lear R, Wisniewski SR, John Rush A, et al. Clinical and demographic factors associated with DSM-IV melancholic depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2006;18:91-8.

- Brodaty H. Melancholia and Ageing Brain. In: Parker G, Hadzi- Pavlovic D, editors. Melancholia: a Disorder of Movement and Mood: a Phenomenological and Neurobiological Review. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996: 237-51.

- Gili M, Roca M, Armengol S, Asensio D, Garcia-Campayo J, Parker G. Clinical patterns and treatment outcome in patients with melancholic, atypical and non-melancholic depressions. PLoS One 2012;7:e48200.

- Caldieraro MA, Baeza FL, Pinheiro DO, Ribeiro MR, Parker G, Fleck MP. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in those with melancholic and nonmelancholic depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 2013;201:855-9.

- Kendler KS. The diagnostic validity of melancholic major depression in a population-based sample of female twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:299-304.

- Wiethoff K, Bauer M, Baghai TC, Möller HJ, Fisher R, Hollinde D, et al. Prevalence and treatment outcome in anxious versus nonanxious depression: results from the German Algorithm Project. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:1047-54.

- Spanemberg L, Caldieraro MA, Vares EA, Wollenhaupt-Aguiar B, Kauer-Sant’Anna M, Kawamoto SY, et al. Biological differences between melancholic and nonmelancholic depression subtyped by the CORE measure. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014;10:1523-31.

- Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Oquendo MA, Burke AK, Mann JJ. Melancholia and the probability and lethality of suicide attempts. Br J Psychiatry 2004;184:534-5.

- Coryell W. The facets of melancholia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2007;433:31-6.

- Austin MP, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, Parker G, Hickie I, Brodaty H, et al. Cognitive function in depression: a distinct pattern of frontal impairment in melancholia? Psychol Med 1999;29:73-85.

- Day CV, Williams LM. Finding a biosignature for melancholic depression. Expert Rev Neurother 2012;12:835-47.

- Parker G, Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Roy K, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. Subtyping depression: testing algorithms and identification of a tiered model. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999;187:610-7.

- Malhi GS, Parker GB, Greenwood J. Structural and functional models of depression: from sub-types to substrates. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;111:94-105.

- Parker G, Blanch B, Paterson A, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Sheppard E, Manicavasagar V, et al. The superiority of antidepressant medication to cognitive behavior therapy in melancholic depressed patients: a 12-week single-blind randomized study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2013;128:271-81.

- Malhi GS, Parker GB, Crawford J, Wilhelm K, Mitchell PB. Treatment-resistant depression: resistant to definition? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;112:302-9.

- Brown C, Battista DR, Sereika SM, Bruehlman RD, Dunbar-Jacob J, Thase ME. Primary care patients’ personal illness models for depression: relationship to coping behavior and functional disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007;29:492-500.