East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2020;30:39-43 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1884

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Ramesh Gupta, FRANZCP, FRCPsych, Senior Consultant Psychiatrist, Headspace Youth Early Psychosis Program, Darwin, NT, Australia

Tamoor Mirza, MBBS, FRANZCP, Clinical Director, Headspace Youth Early Psychosis Program, Darwin, NT, Australia

Muhammad Hassan Majeed, MBBS, MD, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA

Florian Seemüller, MD, Head and Chairman, Kbo Lech-Mangfall Clinic, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany

Hans-Juergan Moeller, MD, Emeritus Professor and ex-Chairman, Department of Psychiatry, Ludwig Maximilian University, Germany

Address for correspondence: Dr Ramesh Gupta, Senior Consultant Psychiatrist, Headspace Youth Early Psychosis Program, Darwin, NT, Australia. Email: gupramkum@gmail.com

Submitted: 10 January 2018 Accepted: 7 August 2019

Abstract

Background: The DSM-IV and the DSM-5 eliminated the importance of the syndromal identity of melancholic depression in favour of a dimensional model within the domain of major depressive disorders. Melancholic depression was excluded from DSM as a distinct disorder owing to the impact of ageing, genetics, and course of illness. We challenge these assertions using retrospective data collected from patients with depression.

Method: Electronic medical records of 1073 patients with depressive-spectrum disorders in 12 centres across Germany spanning from January 2010 to June 2013 were retrospectively reviewed. The diagnosis of melancholia was made using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 21 items (HAMD-21). Patients were followed up every 2 weeks and yearly until discharge from inpatient units. The final dataset consisted of 1014 patients; each had received a minimum of two complete observations.

Results: At baseline, patients with melancholic depression had higher HAMD-21 score than did patients with non-melancholic depression (32.6 vs 23.13, p < 0.001). At the final visit, patients with melancholic depression responded to treatment more often than did patients with non-melancholic depression (81.3% vs 69.04%, p = 0.0156), whereas the two groups were comparable in terms of remission status (50.55 vs 48.68%, p = 0.1943). The relapse rate was higher in patients with melancholic depression than in patients with non-melancholic depression after 1 year (60% vs 45.01%, p = 0.0599), 2 years (77.78% vs 60.36%, p = 0.0233), and 4 years (80% vs 64.45%, p = 0.0452).

Conclusion: Melancholic depression has an identifiable constellation of symptoms and it is not just a severe form of major depression. Melancholic depression is not the result of age-related or pathoplastic changes. We advocate including melancholia as its own illness entity in the next edition of the DSM.

Key words: Depressive disorder; Depressive disorder, major; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Introduction

The DSM-5 has lowered the threshold for the diagnosis of major depression and has given diagnostic importance to non-specific symptoms.1,2 In the DSM-5, clinicians grade the severity of symptoms rather than simply noting their presence or absence. This blurs the diagnostic boundaries between different psychiatric disorders; one example is the removal of the diagnosis of melancholic depression. In DSM-IV, the definition of melancholic depression involves anhedonia and/or lack of mood reactivity, and at least three of the following features: depressed mood, diurnal variation, early awakening insomnia, excessive guilt, anorexia or significant weight loss, and psycho-motor retardation.3 Both the DSM-IV and DSM-5 consider melancholia as a mere specifier within the domain of major depressive disorders for individuals who already meet the criteria for major depression.4,5 After excluding melancholia from the DSM as a distinct category of disorder, the research on melancholia plummeted, and melancholia became a diagnosis of historical importance only.5-7

A similar fate once befell both ‘paranoia’ and ‘hysteria’; however, both have survived their obituarists.8 A consensus paper of 17 field experts led by Gordon Parker advocated that melancholia be positioned as a distinct, identifiable, and specifically treatable affective syndrome in the DSM-IV classification, but this plea had no effect on DSM-5’s designers.

We have drawn information about the elimination of melancholia from the DSM-IV Sourcebook.9 We challenge the premise taken by DSM-IV and provide evidence to support that melancholia has a syndromal identity different from other forms of depression and as a separate disorder. It is not just a severe form of major depression.

In 1930s, depression was considered to exist on a continuum, with different clinical presentations across space and time.10 This model was later refined based on the demographics of patient populations, symptoms, therapeutic interventions and outcomes. Decades later, a clear-cut boundary was set between ‘neurotic’ and ‘endogenous’ depression, with the latter term being used interchangeably with ‘melancholia’.5-7 Similarly, in a cluster analysis–derived grouping of depressed patients, a group of patients with symptoms of endogenous depression was distinguished, characterised by guilt, hopelessness, anorexia, retardation, and early-morning insomnia and delusions.11

The unified concept of depression failed to replicate a bimodal distribution in a discriminant function analysis of patients with neurotic and psychotic depression.12,13 Severity of symptoms was hypothesised to be the principal clinical difference between psychotic and neurotic depression.14

However, others concluded that melancholia was merely a pathoplastic effect of age.15 Therefore, the diagnosis of melancholic depression has decreased in terms of both prevalence and duration of episodes, and the decrease may have resulted from increasingly early diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. All these set the stage for the elimination of melancholic depression as an entity from the psychiatric diagnostic system. Only moderate to severe clinical depression requiring inpatient therapeutic intervention was considered to be endogenous depression (melancholic depression).

The DSM-IV and the DSM-5 categorise melancholic depression and several non-melancholic conditions under major depression. The DSM-IV Sourcebook does not consider melancholic depression as an independent syndrome, because (1) melancholic features do not repeat across episodes, and non-melancholic episodes are likely to become melancholic with increasing age, and (2) melancholia does not breed true in families, and melancholic features are not associated with a unique course of illness. In this article, we challenge these assertions using retrospective data collected from patients with depression.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics review board of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and was conducted from November 2013 to June 2014. 12 centres including seven university hospitals across Germany participated in this study. Electronic medical records of 1073 patients with depressive-spectrum disorders spanning from January 2010 to June 2013 were retrospectively reviewed; 59 of them were excluded because they missed a minimum of two complete follow-ups. Patients were followed up every 2 weeks and yearly until discharge from inpatient care under naturalistic treatment conditions. Annual follow-up for the 4 years revealed that only 78 patients dropped out of the study.

The diagnoses of a depressive-spectrum disorder according to the DSM-IV was confirmed at baseline, at discharge, and at each annual follow-up visit using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.3 The follow-up every 2 weeks included clinician-rated psychopathologic assessments using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 21 items (HAMD-21)16 for diagnosing depression and monitoring recovery. The scale has 21 items; of which eight are scored on a 5-point scale from 0 (not present) to 4 (severe) and nine are scored from 0 to 2. The scoring is based on the first 17 items only, which measure the severity of the depression. The last four items do not measure the severity of depression but highlight the areas that may be related to depression such as paranoia or obsessional and compulsive symptoms. The scale becomes qualitative when more items are taken into account. Patients were allocated into the melancholic group or the non-melancholic group based on specific items such as excessive guilt, insomnia in the early hours of the morning, retardation, agitation, loss of weight, work and activities, and feelings of guilt. Response to treatment was defined as ≥50% decrease in HAMD-21 score, and remission was defined as HAMD-21 score of ≤7.

Patients were treated at the discretion of the psychiatrist-in-charge based on the international clinical guidelines for the treatment of depression.17-19 In addition, medication class, active compounds, dosage, and treatment duration were recorded.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Windows version 22; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). Melancholic and non-melancholic groups were compared using t test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Associations between nominal variables were tested using the Chi-squared test.

Results

At baseline, patients with melancholic depression and patients with non-melancholic depression were comparable with respect to patient age, age of onset, sex, working status, level of education, marital status, duration of hospitalisation, family anamnesis, and duration of the current episode or remission status. However, patients with melancholic depression had higher HAMD-21 score (32.6 vs 23.13, p < 0.001, Table 1).

All patients received antidepressant medication either as monotherapy or co-medication, with 58% receiving sedative compounds and 43% hypnotics. Antipsychotic medications were offered to 44% of the patients.

At the final visit, 67.4% of patients responded to treatment, and 48.97% achieved remission. Patients with melancholic depression responded to treatment more often than did patients with non-melancholic depression (81.3% vs 69.04%, p = 0.0156, Table 1), whereas the two groups were comparable in terms of remission status (50.55 vs 48.68%, p = 0.1943).

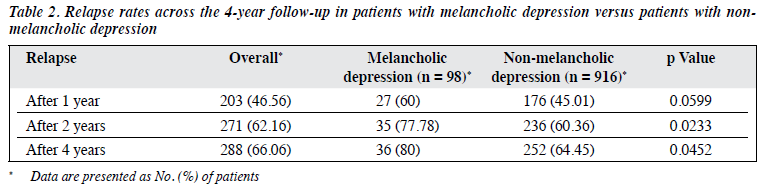

The relapse rate was higher in patients with melancholic depression than in patients with non- melancholic depression after 1 year (60% vs 45.01%, p = 0.0599), 2 years (77.78% vs 60.36%, p = 0.0233), and 4 years (80% vs 64.45%, p = 0.0452) [Table 2].

Discussion

The results suggest that melancholic depression is neither the result of age-related pathoplastic changes nor a severe form of major depression. It has a specific course of illness, and family anamnesis appears irrelevant in the progression of both melancholic and non-melancholic depression.

Patients with melancholic depression had higher baseline HAMD-21 score; these symptoms at presentation were not necessarily as a function of increasing severity in successive episodes or of advancing age. This is consistent with the findings in a 25-year longitudinal comparison study that examined the association between depressive subtypes (endogenous versus neurotic depression).20 No evidence of escalation from non-melancholic to melancholic episodes was reported as a function of increasing age or of recurrence of depressive episodes. Similarly, a retrospective review of long-term followed-up patients did not report any shift from neurotic to psychotic episodes.21 In a 20-year high- intensity follow-up study that measured the influence of ageing and age of onset on the long-term persistence of symptoms in major depression,22 the persistence of depressive symptoms in major depressive disorder did not change when individuals move from the third to the fifth decade of life. Anhedonia and diurnal mood variation are more marked in older patients with melancholia.23 There may be some symptom-specific variation of presentation in these patients.

Family anamnesis is not an essential requirement for the syndromal identity of depression. To ‘breed true’ is a Darwinian concept. It means that an illness has an overall uniform clinical presentation in its pathology, clinical features, course, outcome, and whether it occurs in a set or several sets of populations distributed across space and time.

In the present study, the relapse rate steadily increased yearly in both groups. This indicates consistency in the clinical course and recurrence of symptoms in melancholia. Patients with melancholic depression responded better to the enhanced therapeutic interventions, but they relapsed more often over the 4 years of follow-up. There was no significant difference in remission rate between patients with melancholic depression and patients with non- melancholic depression. Our findings are in accordance with those from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression study that reported similar remission rate between different groups after adjustment for baseline severity.24 Patients with melancholic depression have been reported to have higher relapse rates and poor outcomes.25

Higher relapse rate in melancholia is associated with emerging insensitivity to antidepressant medication.26 This is consistent with our observation that a higher proportion of patients with melancholic depression experienced severe treatment-resistance. Our observations are consistent with previous reports of differential efficacy of antidepressants and electroconvulsive therapy among patients with endogenous depression. Treatment resistance is significantly associated with melancholic features.24 Thus, melancholic depression runs a more protracted course and outcome.

In the present study, major depression and melancholia differed significantly in terms of depression severity as measured by the HAMD-21. This implies that not all severe major depressions are melancholic in nature, but that melancholia usually is severe. This is not surprising given that the ICD-10 allows a diagnosis of melancholia only in moderate to severe depression. Although there is some overlap between severe depression and melancholia, a diagnosis of melancholia requires fulfilment of more HAMD-21 items, which may explain a higher score for melancholic depression.

The higher response to treatment rate observed in patients with melancholic depression was mainly driven by the higher baseline severity, which is known to enhance the response rate to biological treatments. One explanation is that the chances of achieving ≥50% reduction of the HAMD-21 score are higher when the baseline score is higher. In contrast, remission is achieved more easily when the baseline score is lower (closer to the cut-off HAMD-21 score of ≤7). So, if the higher response to treatment rate observed in patients with melancholic depression was the result of a higher baseline severity, a lower remission rate would have been seen. In fact, patients with melancholic depression had a higher (but not significantly) remission rate. This argues against baseline severity as the sole confounder.

In the past, melancholic depression was considered to be just another form of severe major depression.14,27,28 In contrast, the nature of the enquiry (eg, rating the severity of features versus rating the characteristic features) can influence the outcome, and a symptom-based strategy may distinguish melancholic depression from non- melancholic depression.29,30 Clinicians should be mindful of the higher relapse rate and poor response to treatment in long-term management of melancholic depression, which differentiates from other types of depression. Thus, the notion that melancholia is just another form of severe depression is not supported by our findings or other recent studies.

There are a few limitations to our study. A major methodological shortcoming is the retrospective nature of the study. Inter-rater reliability in scoring HAMD- 21, accuracy in family history, and missing data at the 3-year follow-up are other limitations. Results should be interpreted with caution because poor prognosis of patients with melancholic depression can be due to their higher depression severity at the baseline. As the DSM excludes melancholia as a separate disorder, we had to use HAMD-21 criteria to identify these patients. Moreover, data were collected for 4 years only, which may not be enough to monitor the course of illness in some patients. This has practical implication in diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of the illness. An exact diagnosis is necessary for specific clinical recommendations.31 With the correct diagnosis of subtype of depression and appropriate treatment, the distress related to the illness and its related psychological and cognitive effects can be reversed.32-34

Conclusion

Melancholic depression has an identifiable constellation of symptoms that are not simply the pathoplastic effect of age or the result of a shift from non-melancholic to melancholic clinical features in successive episodes. Furthermore, melancholic depression does breed true as a syndrome in the occurrence of its clinical features, in that it has consistent clinical symptoms, course, and outcome. We advocate including melancholia as its own illness entity in the next edition of the DSM.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr Michael Obermeier at the Statistical Department of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich for his assistance. We also thank the private practice official accounts committee of the Canberra Hospital for funding this collaborative study.

Declaration

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Crossref

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, test revision (DSM-IV-TR). American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Parker G. Is the diagnosis of melancholia important in shaping clinical management? Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007;20:197-203. Crossref

- Parker G, McClure G, Paterson A. Melancholia and catatonia: disorders or specifiers? Curr Psychiatry Rep 2015;17:536. Crossref

- Ohmae S. The difference between depression and melancholia: two distinct conditions that were combined into a single category in DSM-III [in Japanese]. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 2012;114:886- 905.

- Day CV, Williams LM. Finding a biosignature for melancholic depression. Expert Rev Neurother 2012;12:835-47. Crossref

- Lewis A. The survival of hysteria. Psychol Med 1975;5:9-12. Crossref

- Rush AJ, Weissenburger JE. Melancholic symptom features and DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:489-98. Crossref

- Lewis A. States of depression: their clinical and aetiological differentiation. BMJ 1938;2:875-8. Crossref

- 1 Paykel ES. Classification of depressed patients: a cluster analysis derived grouping. Br J Psychiatry 1971;118:275-88. Crossref

- Kendell RE, Gourlay J. The clinical distinction between psychotic and neurotic depressions. Br J Psychiatry 1970;117:257-60. Crossref

- Kendell RE. The classification of depressions: a review of contemporary confusion. Br J Psychiatry 1976;129:15-28. Crossref

- Bhrolcháin MN, Brown GW, Harris TO. Psychotic and neurotic depression: 2. Clinical characteristics. Br J Psychiatry 1979;134:94-107. Crossref

- Pull C, Pull MC, Pichot P. Involutional melancholia. 3. Controlled statistical study of the symptomatic originality of depression with late onset, and of the pathoplastic role of age [in French]. Ann Med Psychol (Paris) 1976;1:691-702.

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56-62. Crossref

- Bauer M, Bschor T, Pfennig A, Whybrow PC, Angst J, Versiani M, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Unipolar Depressive Disorders in Primary Care. World J Biol Psychiatry 2007;8:67-104. Crossref

- Hollon SD, Shelton RC. Treatment guidelines for major depressive disorder. Behav Ther 2001;32:235-58. Crossref

- Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Psychiatrie. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie. Praxisleitlinien in Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 5: Behandlungsleitlinien affektive Erkrankungen. 2000. Available at: https://www.leitlinien.de/mdb/downloads/nvl/depression/archiv/ depression-1aufl-vers5-lang.pdf. Accessed 21 March 2018.

- Brodaty H, Luscombe G, Peisah C, Anstey K, Andrews G. A 25-year longitudinal, comparison study of the outcome of depression. Psychol Med 2001;31:1347-59. Crossref

- Lee AS, Murray RM. The long-term outcome of Maudsley depressives. Br J Psychiatry 1988;153:741-51. Crossref

- Coryell W. The facets of melancholia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2007;433:31-6. Crossref

- Hyett MP, Parker GB, Proudfoot J, Fletcher K. Examining age effects on prototypic melancholic symptoms as a strategy for refining definition of melancholia. J Affect Disord 2008;109:193-7. Crossref

- Rush AJ, Warden D, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Gaynes BN, et al. STAR*D: revising conventional wisdom. CNS Drugs 2009;23:627-47. Crossref

- Citalopram: clinical effect profile in comparison with clomipramine. A controlled multicenter study. Danish University Antidepressant Group. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1986;90:131-8. Crossref

- Souery D, Papakostas GI, Trivedi MH. Treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(Suppl 6):16-22.

- Cole J, McGuffin P, Farmer AE. The classification of depression: are we still confused? Br J Psychiatry 2008;192:83-5. Crossref

- Kendler KS, Eaves LJ, Walters EE, Neale MC, Heath AC, Kessler RC. The identification and validation of distinct depressive syndromes in a population-based sample of female twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:391-9. Crossref

- Parker G, Fletcher K, Hyett M, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Barrett M, Synnott H. Measuring melancholia: the utility of a prototypic symptom approach. Psychol Med 2009;39:989-98. Crossref

- Fink M, Bolwig TG, Parker G, Shorter E. Melancholia: restoration in psychiatric classification recommended. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007;115:89-92. Crossref

- Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, Bryant R, Fitzgerald PB, Fritz K, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015;49:1087-206. Crossref

- Rungpetchwong T, Likhitsathian S, Jaranai S, Srisurapanont M. Distress related to individual depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional study in Thai patients with major depression. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:115-20.

- Kumar K, Gupta M. Effectiveness of psycho-educational intervention in improving outcome of unipolar depression: results from a randomised clinical trial. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:29- 34.

- Wong MM, Chan CF, Li SW, Lau YM. Six-month follow-up of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms in late-onset depression. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:146-9.