East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2010;20:31-8

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Farah Malik, PhD, Department of Psychology, GC University, Lahore, Pakistan. Ms Rabia Khawar, MPhil, Department of Psychology, GC University, Lahore, Pakistan.

Dr Haroon Rasheed Chaudhry, MD, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital Lahore, Pakistan. Dr Glyn W. Humphreys, PhD, School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Address for correspondence: Dr Farah Malik, Department of Psychology, GC University, Lahore, Pakistan.

Tel: 92-42-111 000 010 (ext. 307); Email: drfarahmalik@yahoo.com

Submitted: 9 June 2009; Accepted: 11 September 2009

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the impact of duration of untreated psychosis on emotion recognition in patients with first-episode psychosis.

Methods: A sample of 60 patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective and substance-induced psychoses were selected from psychiatric inpatients and outpatients of 3 hospitals in Lahore and 1 in Faisalabad, Pakistan. Patients were divided into short (n = 28) and long (n = 32) duration of untreated psychosis groups, according to whether they had had symptoms for < 80 or ≥ 80 weeks, respectively. Emotion recognition ability was assessed with the help of the Urdu version of a computerised experimental FEEL (Facially Expressed Emotion Labeling) test using 6 basic emotional expressions that appeared on a computer screen followed by possible responses.

Results: Patients with prolonged durations of untreated psychosis showed poorer performance in recognition of facial expressions of emotion than those with short durations of untreated psychosis. This was apparent in general and especially for expressions of anger, surprise, and sadness. First- episode psychosis patients showed higher accuracy rates for recognising positive as opposed to negative emotions. The duration of untreated psychosis correlated positively with positive symptoms of psychosis. Symptom distribution differed across categories of psychosis, but there were similarities in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders.

Conclusions: These findings support recourse to early detection and intervention strategies in psychosis and provide valuable information on how first-episode psychosis patients behave in complex emotional and social situations.

Key words: Emotions; Pakistan; Psychotic disorders; Schizophrenia

摘要

目的:检视首发精神病患者在精神分裂症未治期间的情感识别状况。

方法:於巴基斯坦费萨拉巴德1所医院和拉合尔3所医院的住院和门诊精神病患者中抽样60名符合精神分裂症、分裂情感性异常,和物质引致的精神病的诊断标准,并根据他们精神分裂症未治期的时间分成两组(短时期,即少於80个星期〔n = 32〕和长时期,即80个星期或以上〔n = 28〕)。患者透过於电脑画面出现的6个基本情感表达方式作出反应,并以由巴基斯坦官方语言Urdu版本的电脑实验性工具FEEL以评估他们的情感识别能力。

结果:精神分裂症未治期较长的患者於一般面部情感表达,尤於表达恼怒、惊讶和哀伤方面较另一组别欠佳,而首发精神病患者识别正面情感也较消极情感准确。精神分裂症未治期的长短和精神病正面徵状呈正相关;徵状分布则随着精神病类别而有所不同,但精神分裂症和分裂情感性异常患者则较为相近。

结论:研究支持应及早诊断精神病以作出治疗方案;也为首发精神病患者在复杂情感和其他社交情况的行为表现提供参考理据。

关键词:情感、巴基斯坦、精神失常、精神分裂症。

Introduction

Disturbances in affect recognition may be one of the most pervasive and serious symptoms affecting the psychotic patient’s interpersonal problems. Emotion recognition impairment has been demonstrated in schizophrenia,1 but few studies have examined whether this reflects generalised or specific perceptual deficits or is associated with the illness course. Similar findings have been noted in individuals suffering their first psychotic episode.2

Many of the studies used chronic patients, and therefore presented difficulties in interpretation, due to the confounding influence of institutionalisation, cognitive deficits, positive symptoms, and so on. Studying individuals with ‘first episode,’ ‘first admission,’ ‘early schizophrenia,’ or ‘first-onset’ disorders could be a valuable means of homogenising variability due to the course of the illness.3 If emotion recognition deficits are a feature of schizophrenia, and if these deficits are “stable, vulnerability-linked social cognitive deficits”4 or trait markers rather than an indication of state factors and / or chronicity, then they should be apparent in a first-episode patient sample.

Consideration of impaired social perception and social cognition contribute significantly to the understanding of social behavioural problems in schizophrenia.5 Research has shown that patients with psychosis are impaired in terms of overall recognition of emotions, particularly fear and disgust, and that they did not benefit from increased intensity of stimuli. Error patterns indicated that patients misidentified neutral cues as negative.1 Similar findings have been shown in individuals who suffered from their first episode of psychosis.2 The same study also demonstrated that amygdala dysfunction may contribute to impaired recognition of facial emotions in schizophrenia.

A comprehensive analysis of facial affect recognition research in schizophrenia over the past decade has been published.6 The authors realised that prior to 1986 no facial affect study including individuals with non-schizophrenia psychotic disorders as controls had been published. Another problem identified was that without information about the duration of illness or current mental state, it is difficult to compare patient groups across studies, even when undertaken by the same researchers. Moreover, a first- episode psychosis (FEP) cohort was considered ideal to study subgroups of patients over a range of well-developed facial affect tasks and time periods. Summarising a few multi-channel schizophrenia studies, the authors reported recognition deficits in chronic schizophrenia.6 They also emphasised the need for examination of multi-channel communication in non-chronic and non-acute samples; the performance of psychiatric control groups and the inclusion of individuals with psychotic disorders other than schizophrenia.

Recognition of emotions in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders has been studied to investigate gender differences. Moreover, gender is the only descriptive variable commonly examined in emotion recognition research and the results are mixed. If in fact there is a gender difference in ability, it is very slight and more evident in women. The degree to which males and females differ in perceiving and interpreting different emotions displayed to them has been inspected to analyse which emotions were most susceptible to recognition errors. A significant sex difference was found in patterns of error rates for various tasks. Neutral faces were more commonly mistaken as angry by schizophrenic men, whilst schizophrenic women misinterpreted neutral faces more frequently as sad. Moreover, the faces of females were better recognised.7

Studies on subjective reactions to facial expressions of emotion offer a clearer picture. They indicate that schizophrenic patients are highly sensitive to the distinction between aroused and non-aroused emotions,8 rather than those that between pleasant versus unpleasant emotions.9 The following hypotheses were therefore studied in the current study:

- The duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) will have an impact on emotion recognition in FEP patients, i.e. would patients with longer DUP have more pronounced deficits in emotion recognition tasks?

- Would longer DUP be associated with positive symptoms?

Methods

Participants

A purposive sample of 60 patients with FEP (41 men and 19 women) who met the study inclusion criteria was drawn from psychiatric inpatients and outpatients in different hospitals of Lahore and Faisalabad. These were: the Fountain House Lahore, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital Lahore, the Ahbab Hospital Lahore, and the District Headquarter Hospital Faisalabad in Pakistan. The age range of the sample was 18 to 35 (mean 26, standard deviation [SD] 5) years. Informed consent was obtained from the guardians / caretakers of the patients before their participation in the study. The study comprised a sample of currently psychotic in- and out-patients, as evidenced by delusions, hallucinations, conceptual disorganisation, or unusual thought content (score of ≥ 3 on the respective items of Positive and Negative Symptom Scale [PANSS]). All the patients had been diagnosed by a team of psychiatrists and 2 psychologists. The diagnosis was confirmed with the help of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).10

Instruments

The following measures were used for different types of assessment.

Positive and Negative Symptom Scale

Psychopathology and symptom levels were assessed using the PANSS,11 which is a reliable measure, particularly useful to track changes in such symptoms.12

Global Assessment of Functioning Scale

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale13 is a 100-point tool for rating overall psychological, social, and occupational functioning of persons aged 18 years or more.

Nottingham Onset Schedule

Data on DUP were collected through interviews with the patients, key informants, clinical data sheets and by resorting to the guided interview Nottingham Onset Schedule (NOS).14 This is a short, guided interview and rating schedule to evaluate the onset of psychosis. The NOS provides a standardised and reliable means of recording early changes in psychosis and identifying relatively precise time-points for measuring several durations with respect to any emerging psychosis. By varying the point of onset, it also allows for several ways of defining and measuring treatment delays, including:

- Duration of untreated illness (DOI): from the start of the prodrome (P) to a definite diagnosis (DD);

- Duration of emergent psychosis (DEP): from first psychotic symptom (FPS) to a DD; and

- Duration of untreated psychosis: (i) from the prodrome (DUP I: from P to treatment); (ii) emergent psychosis (DUP II: from FPS to treatment); and (iii) manifestation of the psychosis (DUP III: from DD to treatment).

The DUP we used was defined as the duration of untreated emergent psychosis (from the appearance of FPS to the start of treatment), as has been strongly recommended.14 This definition was used to categorise patients with FEP into 2 groups, namely those having long and short DUP. In the present study sample the median DUP was 80 weeks, and patients were regarded as having short DUPs if the interval was < 80 weeks (n = 28), and the remainder were classified as having long DUPs (n = 32).

Facially Expressed Emotion Labeling Test

The ability to recognise facial emotional expressions was measured with the help of the Facially Expressed Emotion Labeling (FEEL) test,15 which was translated into Urdu for the current study. This is a newly developed computer program in which colour photographs of neutral faces followed by the same faces expressing a certain basic emotion appeared on the screen, and subjects had to identify the emotion shown. The pictures used in the FEEL test were taken from the Japanese and Caucasian Facial Expressions of Emotion series.16 The 6 displayed basic emotions included: anger, sadness, fear, disgust, happiness, and surprise. The task entailed viewing 42 pictures (7 pictures for each emotion) presented on a computer screen. Presentation of the stimulus and selection of the emotion scene proceeded in the same way for all 42 pictures. The FEEL test has shown to have high reliability (Cronbach’s coefficient of α = 0.77).15

Procedure

Almost 90 patients were referred to the researcher by psychiatry consultants of different hospitals in Lahore and Faisalabad. Sixty patients who met the inclusion criteria (based on DSM-IV-TR) were selected. The initial step included the measurement of the baseline characteristics to determine the course and functioning of patients already diagnosed with FEP after obtaining informed consent. The PANSS was used to assess the severity of each patient’s symptoms. The semi-structured NOS questionnaire was used to assess patient demographic characteristics, onset characteristics, clinical status, pre-morbid and more recent social and occupational functioning, family relations, and the DSM-IV-TR diagnosis. The onset of psychosis was defined as the first manifestation of psychotic symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, thought disorder or inappropriate / bizarre behaviour. The DUP was defined as the time interval between the onset of FPS and the start of treatment, which was also assessed with the help of a semi- structured questionnaire.

Regarding the FEEL test, the experimental task for patients with first-episode schizophrenia comprised viewing photographs of faces representing the standardised poses of fundamental emotions, followed by identification of the emotion. In a standardised introduction phase, the test procedure and the meaning of the 6 emotion labels (with the help of synonyms in Urdu language) were explained to the subjects. All the subjects could read and understand the 6 labels presented. For each of the 6 emotions, 8 pictures were displayed. In a warm-up round the subjects saw 6 examples of faces (1 for each emotion) displayed (picture viewing or stimulus) for 0.5 second and were then asked to indicate the displayed emotion by pressing the appropriate computer key. They got feedback on whether their decisions were correct or incorrect. This warm-up was designed to make the subjects familiar with the testing procedure. The remaining 42 pictures (the main test of the 6 emotions with 7 pictures for each) were presented in the same manner without providing any feedback. First a picture of a neutral face was displayed on the computer screen for 1.5 seconds with a short beep to attract the attention of the subject. Then after a 1-second break (with a grey screen) the next stimulus was screened for exactly 0.3 second. This was a picture of the same person but displaying 1 of the 6 basic emotions. First showing the neutral picture and then the emotional face imitates natural conditions, whereby emotion often evolves from a neutral face.

Results

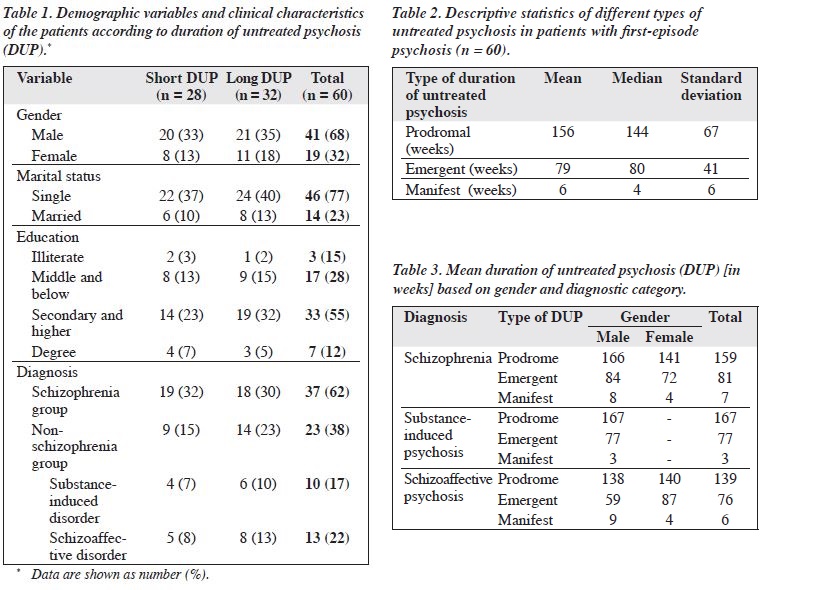

The 2 patient groups with short (n = 28) and long (n = 32) DUPs were categorised using the median DEP of 80 weeks as the cut-off. Similarly patients were divided into 2 groups, using an FEP median cut-off PANSS score of 113 as a measure of psychopathology. The groups represented by severity of illness as high (n = 30) and low (n = 30). This division helped to determine the effect of psychopathology on the ability to recognise emotions. Descriptive statistics for demographic variables are shown in Table 1. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of the 3 types of DUP (prodromal, emergent, and manifest) in the total sample.

Multivariate analysis of variance showed that gender (F [1, 55] = 5.3) and diagnosis (F [2, 55] = 3.2) were found to be significant for their effect on DUP III only (p < 0.05); compared with females (mean [SD], 4.2 [3.9] weeks), males (mean [SD], 7.0 [6.8] weeks) showed a trend towards a longer duration. Patients with substance-induced psychotic disorder experienced shorter durations of untreated manifest psychosis (mean [SD], 3.0 [1.2] weeks) compared with patients with schizophrenia (mean [SD], 7.0 [5.2] weeks) and schizoaffective (mean [SD], 6.1 [6.1] weeks) patient groups. It is important to note here that substance-induced psychotic disorder patients consisted of males only (n = 10). Details are shown in Table 3.

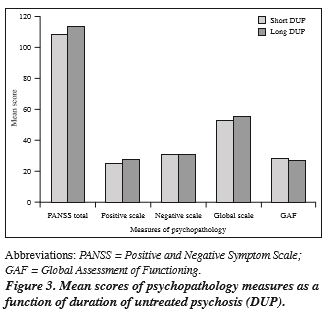

Mean accuracy scores of each emotion category revealed that happiness was the easiest to recognise and disgust was the most difficult. As shown in Figure 1, emotion recognition accuracy for a surprised expression was also higher than that for anger, fear, sadness, and disgust.

A mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with 1 between-subject variable (DUP groups) and 1 within- subject variable (6 different facial expressions of emotions) was performed on FEEL test results to determine if FEP patients had a disproportionate deficit in processing any specific facial expression of emotion.

Analysis of FEEL test data revealed a significant main effect for DUP groups (F [1, 58] = 8.33, p < 0.001) and emotions (F [5, 290] = 58.1, p < 0.001).

Significant differences among groups based on the DUP were found for the total FEEL score of emotion recognition: t (58) = 2.91, p < 0.01; anger: t (58) = 2.05, p < 0.05; surprise: t (58) = 3.29, p < 0.01; and sadness: t (58) = 3.01, p < 0.01. Patients with long DUPs were less accurate on emotion recognition tasks than shorter DUP patients; Figure 2 shows the variation in mean scores in both groups. The ability to recognise the remaining 3 facial expressions did not differ significantly across DUP groups, ie fear: t (58) = 1.17, p > 0.05; disgust: t (58) = 1.31, p > 0.05; and happiness: t (58) = 1.07, p > 0.05.

Effects of Demographic Variables on Emotion Recognition

Separate effects for the demographic variables and clinical characteristics (diagnosis and severity of illness) on emotion recognition ability were also computed, and showed non- significant results for all demographic variables except gender. Gender had a significant effect on the recognition of sad emotional expressions (t [58] = 2.06, p < 0.05) and that females were significantly less accurate (mean = 0.53, SD = 0.84) on the recognition of sadness than males (mean = 1.02, SD = 0.88).

Illness Severity and Emotion Recognition

Significant effects associated with illness severity were present only for anger recognition (t [58] = 2.47, p < 0.01), and not for the other 5 emotions. The FEP patients with more severe symptoms (in terms of PANSS) showed poorer ability to recognise angry facial expressions.

As the recognition of angry facial expressions was also significantly affected by the DUP, the data were further assessed by analysis of covariance after controlling for the severity of illness. Whereas there were non-significant differences for recognition of anger between patients in the short and long DUP groups (F [1, 57] = 2.23, p > 0.05), the differences were significant in those with high versus low levels of illness severity (mean = 0.87, SD = 0.90 vs. 1.53, 1.16) when separately assessed.

Reaction Time for Emotion Recognition Experiment

The ANOVA was to explore differences in average reaction time across groups by 3 factors. This yielded no significant main effects for: DUP (F [1, 50] = 0.60, p > 0.05), diagnosis (F [1, 50] = 0.55, p > 0.05), and severity of illness (F [1, 50] = 1.42, p > 0.05).

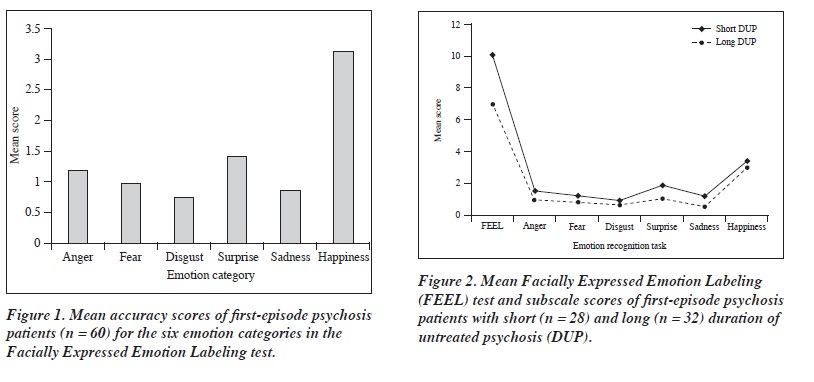

Clinical Characteristics of First-episode Psychosis Patients

Patients in the 3 diagnostic categories had significantly different scores for: PANSS total (F [1, 54] = 8.49, p < 0.001), negative symptoms (F [1, 54] = 4.74, p < 0.01), and the global symptom scale (F [1, 54] = 6.61, p < 0.01).

For PANSS total scores, pairwise comparisons with least significant difference post hoc were conducted among diagnostic categories. These revealed highly significant mean differences for the schizophrenia (mean = 113.93, p < 0.001) and schizoaffective (mean = 108.76, p < 0.003) groups in comparison with substance-induced psychosis group (mean = 99.83). The results were non-significant when the schizophrenia and schizoaffective groups were compared.

The different DUP groups also showed significant differences for PANSS total scores (F [1, 54] = 3.96, p < 0.05) and positive symptom scale scores (F [1, 54] = 5.47, p < 0.05). Patients with long DUP experienced more positive symptoms (mean = 26.99, SD = 0.73) compared with short DUP patients (mean = 24.29, SD = 0.88). The interaction of both factors (ie DUP groups and diagnostic categories) was also highly significant for total PANSS scores (F [1, 54] = 8.49, p < 0.001), positive symptom (F [1, 54] = 7.11, p < 0.01), and global symptom scales (F [1, 54] = 5.26, p < 0.01). This indicated that at least 1 of the 3 diagnostic categories differed on the scales, as a function of DUP (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our results suggest that the DUP for all diagnostic categories of psychosis (ranging from 12 to 192 weeks) was not very long, although they were slightly longer in patients with schizophrenia than in those with schizoaffective and substance-induced disorders. There were significant differences in DUP III depending on gender and diagnostic category. In this study, our major concern was the DUP in reference to manifestation of the FPS up to the initiation of treatment. Our results suggested that it was not different across the diagnostic categories of psychosis, showing that patients did not take much time to avail themselves of treatment after being diagnosed. Later on, the sample was divided into 2 groups (with short and long DUPs) based on the median delay of 80 weeks, so as to explore the effects of other variables. The division of the sample on the basis of the median DUP has been reported in many previous studies,14,17-19 which nevertheless indicated marked variation,20 consistent with differences in study populations, definition of DUP, and statistical methods.

Moreover individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorders displayed a significantly shorter delays than those with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders. Regarding the shorter DUP for subjects with substance- induced psychotic disorder, sometimes such patients are already under medical supervision (possibly for physical and / or psychotic symptoms), which may facilitate earlier diagnosis and treatment. Moreover, their families or caretakers may already be concerned to seek out treatment when their psychotic symptoms emerge, particularly if the latter are very prominent and thus easily identified. The interval from definite psychotic symptoms until treatment differed for men and women; men had longer delays. These delays in treatment also indicate a crucial point of view about psychosis in our society. Thus, the stigma due to such illness still leads parents or guardians to either negate or try and hide the problem and avoid recourse to psychiatrists for early treatment.

An important objective of our study was to determine the level of emotion recognition in FEP patients and to compare it in long and short DUP groups. The results of emotion recognition demonstrated that the ability to recognise facial expressions of emotions varied markedly in patients with FEP. Mean differences revealed that accuracy responses were highest for the happy facial expression. Recognition of surprise was second easiest recognisable expression followed by anger. The results of our study were consistent with previous findings from an extensive meta-analysis in schizophrenic patients,6 which suggested surprise to be the second easiest emotion to recognise after happiness, whilst fear was among the hardest to recognise. Recognition rates in our study were also high for angry facial expressions. Our results indicate a general trend regarding emotion-specific recognition deficits of FEP patients maximal for the negative emotions, as identified by many other researchers.21,22 Thus, the major deficits were for fear, sadness, and disgust that could all be categorised as negative emotions, which was in contrast to the other 3 emotion categories. Disgust was the most difficult expression to recognise for FEP patients, but needs further investigation (in comparison with healthy controls), as this particular emotion might not be easily recognised even by normal people. Inability to recognise negative as opposed to positive emotions was supported by other existing data. Negative affect seems to be differentially affected, which may well be evident in the early course of schizophrenia.23 Difficulty in recognising sad facial expressions has also been reported before,24-26 though most studies were directed at investigating generalised emotion recognition deficits, as opposed to specific deficit categories.27-29

Moreover, according to our hypothesis, FEP patients would show generalised as well as specific deteriorations in the ability to recognise emotions as a result of treatment delay. Patients with longer DUP performed significantly less well on the FEEL test in general than those with shorter DUP. Significant impairment was present in the recognition of sad, surprised, and angry facial expressions; yet the lack of a control group hindered interpretation of the overall poor performance by FEP patients for all emotion categories. Further analysis of individual scores in each emotion category relative to the scores in the other 5 emotions and the total test score is strongly recommended. This may reveal which of the emotion categories were more difficult for FEP patients to label. Scarcity of data on the impact of DUP on emotion recognition should be taken into consideration while interpreting these results. When grouped according to treatment delay, differences in recognition of certain emotional expressions could be related to face-processing component deficits that underlie the structural encoding of facial features, as described in patients with schizophrenia.29 This neurobiological phenomenon is being studied by many researchers in western countries.

Our results also suggest that the diagnosis per se could not account for differences in emotion recognition; all 3 patient groups were alike in their performance of recognition tasks, which was contrary to some previously reported findings.2 Similarly, emotion recognition tasks were not affected significantly by demographic variables such as education level. Gender differences were also non- significant for overall and individual emotion category FEEL test performances, except for sadness. Interestingly, men recognised emotions better than women. Nor did severity of illness yield pronounced effects, except for anger recognition that was more impaired with higher levels of illness severity. This suggests that recognition of angry facial expressions might be related to the expression of anger that is often an important feature of psychosis. Thus, investigation of the relationship between expressed emotions and emotion recognition could well be revealing. Deficits in facial affect recognition are well documented in psychosis and have been associated with reduced social functioning and interpersonal difficulties.30

The degree to which males and females differ in perceiving and interpreting the different emotions revealed significant results only for sad expressions. Males performed better on sadness recognition, which was contrary to previous report.31 The same study also suggested that the better course and outcome of female patients with psychosis were related to better emotion recognition, as they show better social skills than their male counterparts. Healthy women also outperform men in emotion recognition and empathic capacity.31 Studying sex differences in emotional processing might contribute to a better understanding of differences between males and females in relation to the clinical manifestations of their illness. None of the independent variables like DUP, illness severity, diagnosis, or gender significantly affected the average time taken by the patients to recognise emotions. This finding was consistent with the general emotive literature, there being no evidence for a gender or age effect.6

Overall, the distribution of positive and negative symptoms differed across diagnostic categories, though there were similarities with respect to schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, possibly because both manifest more severe symptoms than patients with substance- induced psychosis. Furthermore, positive symptoms were more evident when there was a treatment delay (longer DUP).

In conclusion, FEP patients showed better ability to recognise positive emotions (happiness and surprise) than all negative emotions. Patients with longer DUPs demonstrated a poor ability to recognise facial expressions of emotions in general, and particularly anger, disgust, and sad emotional expressions. The reaction time of emotion recognition was not affected by DUP or any other studied variable. Males performed better than females in recognising expression of sad emotions. Other demographic variables did not contribute to outcomes.

Limitations and Suggestions

Certain limitations did not permit the investigation of many aspects that could have been of great value:

- As in other clinical studies, our small sample size was an issue, curtailing the generalisation of our findings;

- Our study did not include a control group, which could have entailed healthy individuals or patients with mental illness other than psychosis;

- The diagnostic heterogeneity of the sample in terms of psychotic categories could have affected overall DUP outcome measures;

- In a natural environment, social expressions are not akin to still photographs; rather they correspond to ever-changing events. Further studies could use videotaped demonstrations of facial expressions to dealing with this issue.

Implications

Although it is difficult to compare the overall efficacy of these findings in the absence of a control group and adequate follow-up, our findings are worth considering as an important element pertinent to future models of DUP research and outcomes in Pakistan. Overall, our study could be regarded as very important as a baseline for providing clues for early detection and for developing management plans for patients with psychosis in Pakistan. Facial processing is a main characteristic of interpersonal communication and a vital element of social behaviour. Impairment may also lead to poor judgement in social interactions and behavioural disturbances. Further studies are required to explain the relationship between facial affect recognition deficits, behavioural disturbances, and inappropriate social interactions in FEP patients, with a special emphasis on DUP.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of Prof. Hoffman (University of Ulm, Germany) for providing us with the FEEL task and Marx Cox who helped in translating the test in Urdu. Lilly and Pfizer pharmaceuticals are also acknowledged for their financial support. We are also grateful to Nilufar Mossaheb, Monika Schloegelhofer, Rainer M. Kaufman, and Herald Aschauer (Division of Biological Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical University of Vienna), for providing us with the instruments for assessment of Duration of Untreated Psychosis (DUP). The data on DUP are also being used in a research project “Effect of DUP on cognitive impairment” in collaboration with team from Vienna.

References

- Kohler CG, Turner TH, Bilker WB, Brensinger CM, Siegel SJ, Kanes SJ, et al. Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: intensity effects and error patterns. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1768-74.

- Edwards J, Pattison PE, Jackson HJ, Wales RJ. Facial affect and affective prosody recognition in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2001;48:235-53.

- Keshavan MS, Schooler NR. First-episode studies in schizophrenia: criteria and characterization. Schizophr Bull 1992;18:491-513.

- Penn DL, Corrigan PW, Bentall RP, Racenstein JM, Newman L. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Psychol Bull 1997;121:114-32.

- Brüne M. Emotion recognition, ‘theory of mind’, and social behavior in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2005;133:135-47.

- Edwards J, Jackson HJ, Pattison PE. Emotion recognition via facial expression and affective prosody in schizophrenia: a methodological review. Clin Psychol Rev 2002;22:789-832.

- Weiss EM, Kohler CG, Brensinger CM, Bilker WB, Loughead J, Delazer M, et al. Gender differences in facial emotion recognition in persons with chronic schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 2007;22:116-22.

- Pilowsky I, Bassett D. Schizophrenia and the response to facial emotions. Compr Psychiatry 1980;21:236-44.

- Mandal MK, Pandey R, Prasad AB. Facial expressions of emotions and schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull 1998;24:399-412.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987;13:261-76.

- Kay SR. Positive-negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia: psychometric issues and scale comparison. Psychiatr Q 1990;61:163-78.

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976;33:766-71.

- Singh SP, Cooper JE, Fisher HL, Tarrant CJ, Lloyd T, Banjo J, et al. Determining the chronology and components of psychosis onset: The Nottingham Onset Schedule (NOS). Schizophr Res 2005;80:117-30.

- Kessler H, Bayerl P, Deighton R, Traue HC. Facially Expressed Emotion Labeling (FEEL): PC gestuetzter Test zur Emotionserkennung [In German]. Verhaltenstherapie und Verhaltensmedizin 2002;23:297- 306.

- Matsumoto D, Ekman P. Japanese and Caucasian Facial Expressions of Emotion (JACFEE) and Neutral Faces (JACNeuF) [slides]. San Francisco: Department of Psychiatry, University of California; 1988.

- Drake RJ, Haley CJ, Akhtar S, Lewis SW. Causes and consequences of duration of untreated psychosis in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:511-5.

- Clarke M, Whitty P, Browne S, McTigue O, Kamali M, Gervin M, et al. Untreated illness and outcome of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:235-40.

- Uçok A, Polat A, Genç A, Cakir S, Turan N. Duration of untreated psychosis may predict acute treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 2004;38:163-8.

- Norman RM, Malla AK. Duration of untreated psychosis: a critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med 2001;31:381-400.

- Mandal MK, Jain A, Haque-Nizamie S, Weiss U, Schneider F. Generality and specificity of emotion-recognition deficit in schizophrenic patients with positive and negative symptoms. Psychiatry Res 1999;87:39-46.

- Muzekari LH, Knudsen H, Evans T. Effect of context on perception of emotion among psychiatric patients. Percept Mot Skills 1986;62:79- 84.

- Habel U, Krasenbrink I, Bowi U, Ott G, Schneider F. A special role of negative emotion in children and adolescents with schizophrenia and other psychoses. Psychiatry Res 2006;145:9-19.

- Archer J, Hay DC, Young AW. Movement, face processing and schizophrenia: evidence of a differential deficit in expression analysis. Br J Clin Psychol 1994;33:517-28.

- Mandal MK, Borod JC, Asthana HS, Mohanty A, Mohanty S, Koff E. Effects of lesion variables and emotion type on the perception of facial emotion. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999;187:603-9.

- Kohler CG, Bilker W, Hagendoorn M, Gur RE, Gur RC. Emotion recognition deficit in schizophrenia: association with symptomatology and cognition. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:127-36.

- Kerr SL, Neale JM. Emotion perception in schizophrenia: specific deficit or further evidence of generalized poor performance? J Abnorm Psychol 1993;102:312-8.

- Hooker C, Park S. Emotion processing and its relationship to social functioning in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res 2002;112:41- 50.

- Turetsky BI, Kohler CG, Indersmitten T, Bhati MT, Charbonnier D, Gur RC. Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: when and why does it go awry? Schizophr Res 2007;94:253-63.

- Williams BT, Henry JD, Green MJ. Facial affect recognition and schizotypy. Ear Intervention in Psychiatry 2007;1:177-82.

- Scholten M. Schizophrenia and sex differences in emotional processing [document on the Internet]. Medical News Today online; 2007 March 26. Available from: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/66129.php. Accessed 25 Mar 2008.