East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2010;20:180-5

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prof Edwin Lee, MRCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Chor-ming Lum, MD, Department of Medicine, Shatin Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Prof Yu-tao Xiang, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Prof Gabor Sador Ungvari, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Prof Wai-kwong Tang, MD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for Correspondence: Prof Wai-kwong Tang, Department of Psychiatry, 7AB, Shatin Hospital, Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 2636 7754; Fax: (852) 2647 5321;

Email: tangwk@cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 21 April 2010; Accepted: 6 September 2010

Abstract

Objectives: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with physical and psychological burdens. Although there is research about health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of such patients, less is known about the psychosocial condition of their family caregivers. The objectives of this study were to examine the HRQOL and the burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patient caregivers, and to identify associated relevant factors.

Methods: A total of 81 eligible caregivers completed a caregiver survey on HRQOL (Short Form–36

Questionnaire), caregiving burden (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, CIRS) and other biopsychosocial factors. Descriptive statistics, correlations, and multiple linear regression models were used to analyse data.

Results: The caregiver’s Mental Component Summary measure of the Short Form-36 was associated with each caregiver’s total CIRS scores, the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and the Lubben Social Network Scale. The caregiver’s Physical Component Summary measure was associated with the patient’s disability allowance, the caregiver’s total CIRS score, and the Barthel Index score. Caregivers’ Caregiving Burden Scale scores were associated with their Geriatric Depression Scale total score and the need to take care of other family members.

Conclusions: This study demonstrates that depressive and anxiety symptoms are associated with caregivers’ burden and HRQOL. Further studies on evaluating interventions on caregivers’ HRQOL and burden should take mood symptoms into consideration.

Key words: Caregivers; Cost of illness; Pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive; Quality of life

摘要

目的:慢性阻塞性肺病与生理和心理负担相关。虽然已有与患者健康相关生活水平的研究,不 过,有关患者的家庭照顾者其心理社会状况却所知不多。本研究旨在检视上述的生活水平和这 些照顾者的负担,以及确认相关要素。

方法:81名照顾者完成针对与健康相关生活水平的照顾者调查(SF-36)、以累积性疾病评量 表评估他们的负担,并分析其他生物心理社会因素。研究并以描述统计、相关系数和多元线性 回归法作数据分析。

结果:根据SF-36问卷结果,照顾者的心理範畴总分与他们的总累积性疾病评量表分数、医院焦 虑忧鬱量表和长者支援网络量表相关。照顾者的生理範畴总分,则与患者的伤残津贴、照顾者 的总累积性疾病评量表分数和巴氏量表比分呈相关。此外,照顾者的照顾负担量表比分与他们 的老人抑鬱量表总分,以及照顾其他家庭成员需要的因素相关。

结论:研究结果显示,抑鬱和忧虑徵状与照顾者的负担和与健康相关生活水平相关。针对上述 问题的干预的进一步研究,应把情绪徵状纳入研究範围内。

关键词:照顾者、病症费用、肺病,慢性阻碍、生活水平

Introduction

Caregiving refers to the experiences and tasks about providing assistance to a family member who is no longer independent.1 Burden of care indicates “the extent to which caregivers perceive their emotional or physical health, social life, and financial status suffering as a result of caring for their relative”.2 Objective burden of care reflects the disruptions in family life and the tasks and activities associated with providing care, whereas subjective burden of care focuses on perceived stress associated with providing care.3 Subjective burden of care is related to many factors, such as the length of caregiving time entailed, the type of caregiving tasks, family stressors, and the physical condition of the care recipient.4

Severe and progressive dyspnoea is the most devastating and frequent complaint of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).5 Pervasive dyspnoea is frightening to both the patient and caregiver, and can lead to stress.6 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can result in physical disability, altered cognition, memory disturbances, and behavioural changes that may further increase the burden of care.7

Caregivers of COPD patients often have additional roles such as decision-maker and finance manager.8 They have to deal with patient attitudes and irritability.8 Sexton9 reported that wives of COPD patients felt guilty about causing their husbands respiratory distress and thus limited the expression of strong feelings. The experience of a wife caregiver has been described as a mixture of anger, helplessness, guilt and isolation.10 Wives of COPD patients were deemed to have lost freedom, because they had relinquished recreational and social activities.8,10 Even their shopping trips were constrained, as they opted to stay at home as much as they could in order to avoid conflicts.11 Persistent worry about the patients’ health and symptoms was common, and wives frequently experienced fatigue and difficulty sleeping.8,10

Positive sides to caregiving were also described, which included the satisfaction from easing their husbands’ suffering and helping them to stay at home as long as possible. This positive experience of caregiving was also related to the presence of family, children and grandchildren.11 Ways of coping with the caregiving role reported by COPD wives included: finding personal satisfaction, successfully managing their husband’s behaviour, finding meaning in the caregiving situation, managing their own distress, and finding support when expressing their feelings.12

Compared with wives of husbands without COPD, wives of COPD patients reported lower levels of life satisfaction.8 Predictors of life satisfaction included the Subjective Stress Scale score,13 satisfaction with money available, and the working status of the COPD wives.8 Ross and Graydon10 found that perceptions of their own health by COPD wives were correlated with their mood and social support. Wives of COPD patients found it hard to ask relatives for help, and needed increased support from the health care system.11 Useful help might include: caregiving guidance and information delivery,14 as well as counselling, and coaching in relaxation techniques.8 Further support to carers could be provided via regular carers’ group meetings and enhancement of informal support from family members and friends.8,14 Respite care may provide relief to carers.10,14

Patients with COPD need assistance from their significant others so as to cope with activities of daily living.8 The presence of a significant person at home is the single most important factor facilitating the adjustment to COPD patients. This study aimed to examine the health- related quality of life (HRQOL) and burden of caregivers of patients with COPD, and to identify associated relevant factors.

Methods

Study Design

A clinically convenient sample of Hong Kong community- dwellers followed up in a university chest clinic and their caregivers were recruited. Eligible cases were identified from the Prince of Wales Hospital from 2006 to 2007. The inclusion criteria were: (1) aged above 18 years; (2) Chinese ethnicity; (3) diagnosis of COPD; (4) presence of a family caregiver; and (5) ability to give informed consent. Patients with other physical co-morbidities like pneumoconiosis and stroke were excluded. The recruited caregivers were examined by physiological and psychological tests, as well as caregiving burden and HRQOL measures. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Study Instruments

Measures Directed at the Patients

All the patients underwent spirometry with a portable device (Micro Medical Limited, UK). After undertaking at least 3 forced expiratory manoeuvres, the largest forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were recorded as the response to bronchodilators.15 Each patient’s height and weight were measured and predicted values for lung function parameters (FEV1% and FVC%) based on Asian population norms were derived. Spirometry was performed by a research assistant, who had received adequate training from one of the authors. Perceived patient breathlessness was assessed using the Medical Research Council Dyspnoea Scale (detailing 5 grades of disability). The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) was used to assess multi-morbidity.16 The CIRS takes into account the number of medical problems, weights them according to severity, and generates a more accurate assessment of patient health. The Six-minute Walk Test was used to assess functional capacity.17 The Barthel Index (BI) was administered to measure daily functioning, specifically the activities of daily living and mobility.18 The Chinese version of the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used to measure the severity of patients’ depressive symptoms.19 Although the GDS was originally designed for elderly persons, it has also been shown to be a valid and reliable instrument in non-elderly adults.20 The Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL) was used to measure the functional impact of emotional, cognitive, and physical impairments.21

Measures Directed at the Caregivers

The validated Chinese version of Short Form–36 Questionnaire (SF-36) was administered to assess the HRQOL,22 which is a multi-purpose, short-form health survey. It yields an 8-scale profile of functional health and well-being scores, as well as psychometrically based physical and mental health summary measures. Lower scores correspond to worse HRQOL. The Caregiving Burden Scale (CBS) was used as a self-administered survey which assesses direct, instrumental, and interpersonal caregiving tasks.23 Each caregiver rated 15 caregiving tasks for the amount of time spent (objective burden) and level of difficulty (subjective burden) assessed using 5-point Likert scales. Scores ranged from 15 to 75 with a higher score reflecting more burdens. The Chinese version of the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS) was administered to measure social support. The LSNS consists of 10 questions.24 Scores for individual items range from 0 to 5. A higher score reflects a better social network. The Chinese version of the LSNS has been validated in Hong Kong.25 The Mini-Mental State Examination was used as a brief mental state examination to assess cognitive abilities.26 The CIRS, BI, IADL and GDS were used to measure the general health, functioning and depressive symptoms of caregivers. In addition to GDS, anxiety symptoms were measured by the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.27

Statistical Analysis

Data were reported as means (standard deviations [SDs]) unless otherwise specified. Demographic data of included and excluded patients were compared using Student’s t and Fisher’s exact tests. Descriptive statistics were computed for each of the analysed variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Spearman’s rho were calculated to study the relationship between the CBS, SF-36 scores and other variables.

Multiple linear regression models were prepared for CBS and SF-36 scores. For each of these regression models, predictor variables were entered if these variables met a criterion p value (< 0.10) in bivariate models. The correlations between the variables were also examined. If the correlation between any pairs of the variables was greater than 0.50, one of them was removed from the final model to avoid multi-collinearity. Statistical significance was set at less than 0.05. All statistical tests were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Windows version 14.0.

Results

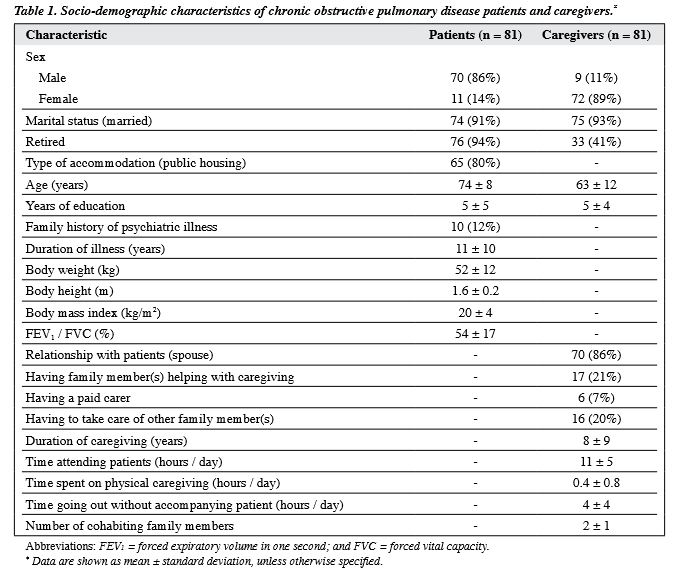

We approached 498 patients followed up during the study period, of whom 417 were excluded (250 did not have family caregivers, 43 had other physical co-morbidity, 62 refused to participate, and 62 for other reasons). Thus, 81 patients and their families were recruited to participate in this research. Regarding the patients, 70 (86%) were male, and their mean (SD) age was 74 (8) years. Regarding the caregivers, 72 (89%) were female and their mean (SD) age was 63 (12) years; 75 (93%) were married, 70 (86%) were spouses, the mean (SD) years spent having formal education was 5 (4) years. The other socio-demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Caregiver’s Health-related Quality of Life and its Association with Other Variables

Their mean (SD) Mental Component Summary score for the SF-36 was 54 (10) [mental health, 74 (20); role emotional, 74 (40); social functioning, 90 (23); and vitality, 58 (22)]. This was associated with caregiver’s total CIRS scores, and scores for the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and the LSNS which accounted for 29% of the variance.

The caregiver’s mean (SD) Physical Component Summary score of the SF-36 was 58 (9) [physical function, 83 (16); role physical, 74 (33); bodily pain, 62 (30); and general health, 56 (23)]. The caregiver’s mean Physical Component Summary measure of the SF-36 was associated with patient’s disability allowance, the total CIRS score and the BI score, which collectively accounted for 31% of the variance.

Caregiving Burden and its Association with Other Variables

The mean (SD) CBS score was 50 (14). The mean (SD) duration of caregiving was 8 (9) years. The mean (SD) time they attended the patient was 11 (5) hours per day, and 0.4 (0.8) hour per day was spent on physical caregiving. The caregivers had a mean (SD) number of cohabiting family members of 2 (1) with 0.3 (0.8) family member help with caregiving (n = 17, 21%). There were 6 caregivers (7%) who provided paid assistance and 16 (20%) who also cared for other family members. The caregivers had a mean (SD) of 4 (4) hours per day to go out without accompanying the patient. The CBS score was correlated with caregiver’s GDS total score and the need to take care of other family members. The clinical correlates of COPD patients and carers’ CBS and SF-36 summary scores are listed in Table 2.

Discussion

This study investigated the psychosocial condition of caregivers in a community sample of Chinese patients with COPD. The psychological well-being of caregivers was associated with their physical health, anxiety symptoms, and social support. Anxiety symptoms in COPD caregivers have not been examined systematically, although they are common in caregivers of patients with dementia,28 and those with chronic physical illness,29 and heart transplant recipients.30 Emotional distress was encountered in COPD caregivers with little support and assistance.31 This may be related to their dissatisfaction about the lack of recreation and support from friends, families and health care providers.11 Nijboer et al32 suggested that caregivers with a low level of daily emotional support perceived caregiving in a more negative way and were identified as becoming more depressed over time. The caregiver’s perception is important, as active helping predicts greater caregiver’s positive affect, and helping valued loved ones may promote caregivers’ well-being.33 In the Chinese, it is less common for people to share their feelings with others as compared with western subjects. Encouragement of communication between patients and caregivers helps lessen the latter’s burden.34 Caregivers with poor social support should be identified, so as to provide psychosocial intervention and promote better care of COPD patients. Telephone-based enhanced training (sessions promoting physical activity, relaxation, cognitive restructuring, communication skills, and problem solving) has been suggested to assist delivery of coping skills training to care for patients with COPD and change the way they are routinely managed in order to reduce distress, enhance quality of life, and potentially improve medical outcomes.35

Limitations

First, the caregiver sample recruited in this study may not be representative of other COPD caregivers. Second, this was a cross-sectional study and could not reveal the effect of the caregiving trajectory on the caregiving burden and caregivers’ QOL. Furthermore, a range of social support services were provided for patients and caregivers, such as housekeeping services, meal delivery, volunteer visits, and training in relaxation and problem-solving skills. These services may help to ease the caregiving burden and improve the caregivers’ QOL, but the extent of their efficiency was not explored. Longitudinal studies are warranted to gain a clearer picture of caregiving and the role of social support services in caring for COPD patients. Despite these methodological limitations, the present study has examined the caregiving burden and HRQOL in caregivers of patients with COPD.

Conclusions

This study has shown that patients’ mental and physical symptoms can affect their caregiver’s HRQOL and caregiving burden. These findings are useful in the planning of services targeting caregivers for patients with COPD. The inclusion of mood symptoms, HRQOL and caregiving burden measures may provide a more comprehensive assessment of the overall psychosocial condition of patients and their caregivers. Further research is needed to examine whether HRQOL and the caregiving burden of caregivers can affect patient outcome.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by Pneumoconiosis Compensation Fund Board Research Grant.

References

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990;30:583-94.

- Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist 1986;26:260-6.

- Biegel DE, Song LY, Chakravarthy V. Predictors of caregiving burden among support group members of persons with chronic illness. In: Kahana E, Biegel DE, Wykle ML, editors. Family caregiving across the life span. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications; 1994: 178-215.

- Mui AC. Caregiver strain among black and white daughter caregivers: a role theory perspective. Gerontologist 1992;32:203-12.

- Ahleit BD. Interventions for clients with lower respiratory problems. In: Ignatavicius DD, Workman ML, Mishler MA, editors. Medical- surgical nursing: a nursing process approach. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders WB; 1995: 673-728.

- Shekleton ME. Coping with chronic respiratory difficulty. Nurs Clin North Am 1987;22:569-81.

- Cain JC, Wicks MN. Caregivers attributes as correlates of burden in family caregivers coping with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Fam Nurs 2006;6:46-68.

- Sexton DL, Munro BH. Impact of a husband’s chronic illness (COPD) on the spouse’s life. Res Nurs Health 1985;8:83-90.

- Sexton DL. The supporting cast: wives of COPD patients. J Gerontol Nurs 1984;10:82-4.

- Ross E, Graydon JE. The impact on the wife of caring for a physically ill spouse. J Women Aging 1997;9:23-35.

- Bergs D. “The Hidden Client” — women caring for husbands with COPD: their experience of quality of life. J Clin Nurs 2002;11:613- 21.

- Buffum MD, Brod M. Humor and well-being in spouse caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Appl Nurs Res 1998;11:12-8.

- Chapman JM, Reeder LG, Massey FJ Jr, Borun ER, Picken B, Browning GG, et al. Relationships of stress, tranquilizers, and serum cholesterol levels in a sample population under study for coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol 1966;83:537-47.

- Cossette S, Levesque L. Caregiving tasks as predictors of mental health of wife caregivers of men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Res Nurs Health 1993;16:251-63

- Fletcher CM, Elmes PC, Fairbairn AS, Wood CH. Significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population. Br Med J 1959;2:257-66.

- Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1968;16:622-6.

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111-7.

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61-5.

- Lim PP, Ng LL, Chiam PC, Ong PS, Ngui FT, Sahadevan S. Validation and comparison of three brief depression scales in an elderly Chinese population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15:824-30.

- Rule BG, Harvey HZ, Dobbs AR. Reliability of GDS in adult population. Clin Gerontol 1989;9:37-43.

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179- 86.

- Lam CL, Gandek B, Ren XS, Chan MS. Tests of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1139-47.

- Gerritsen JC, van der Ende PC. The development of a care-giving burden scale. Age Ageing 1994;23:483-91.

- Lubben JE. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam Community Health 1988;11:42-52.

- Chou KL, Chi I. Stressful life events and depressive symptoms: social support and sense of control as mediators or moderators? Int J Aging Hum Dev 2001;52:155-71.

- Chiu HF, Lee HC, Chung WS, Kwong PK. Reliability and validity of the Cantonese version of Mini-Mental State Examination: a preliminary study. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 1994;4(Suppl):S25-28.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361-70.

- Russo J, Vitaliano PP, Brewer DD, Katon W, Becker J. Psychiatric disorders in spouse caregivers of care recipients with Alzheimer’s disease and matched controls: a diathesis-stress model of psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol 1995;104:197-204.

- Karlin NJ, Retzlaff PD. Psychopathology in caregivers of the chronically ill: personality and clinical syndromes. Hosp J 1995;10:55- 61.

- Dew MA, Myaskovsky L, DiMartini AF, Switzer GE, Schulberg HC, Kormos RL. Onset, timing and risk for depression and anxiety in family caregivers to heart transplant recipients. Psychol Med 2004;34:1065- 82.

- Spence A, Hasson F, Waldron M, Kernohan G, McLaughlin D, Cochrane B, et al. Active carers: living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Palliat Nurs 2008;14:368-72.

- Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Triemstra M, van den Bos GA, Sanderman R. The role of social and psychologic resources in caregiving of cancer patients. Cancer 2001;91:1029-39.

- 33. Poulin MJ, Brown SL, Ubel PA, Smith DM, Jankovic A, Langa KM. Does a helping hand mean a heavy heart? Helping behavior and well-being among spouse caregivers. Psychol Aging 2010;25:108- 17.

- Fried TR, Bradley EH, O’Leary JR, Byers AL. Unmet desire for caregiver-patient communication and increased caregiver burden. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:59-65.

- Blumenthal JA, Keefe FJ, Babyak MA, Fenwick CV, Johnson JM, Stott K, et al. Caregiver-assisted coping skills training for patients with COPD: background, design, and methodological issues for the INSPIRE-II study. Clin Trials 2009;6:172-84.