East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2012;22:105-9

THEME PAPER

Development of an Early Psychosis Intervention System in Korea: Focus on the Continuing Care System for First-episode Psychosis Treatment in Seoul

韩国首尔早期思觉失调干预系统的发展:持续护理为主的首发 思觉失调治疗

Mr Myung-Soo Lee, MD, MPH, Seoul Mental Health Center, Seoul, Korea.

Ms So-Ra Ahn, PRN, MPH, Seoul Mental Health Center, Seoul, Korea.

Dr Jong-Il Park, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Research Institute of Clinical Medicine and Institute for Medical Sciences, Chonbuk National University, Jeonju, Korea.

Prof. Young-Chul Chung, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Research Institute of Clinical Medicine and Institute for Medical Sciences, Chonbuk National University, Jeonju, Korea.

Address for correspondence:Prof. Young-Chul Chung, Department of Psychiatry, Chonbuk National University Medical School, 567 Baekje-Daero, Deokjin-Gu, Jeonju-Si, Jeollabuk-Do, 561-756 Korea.

Tel: (82-63) 250 2185; Fax: (82-63) 275 3157; email: chungyc@jbnu.ac.kr

Submitted: 5 April 2012; Accepted: 17 May 2012

Abstract

Providing intensive psychosocial intervention within the 5-year critical period following the first psychotic episode is important for both symptomatic and functional recovery. Recently, community mental health centres in Korea have begun to shift their main roles from care of those with chronic schizophrenia to early detection of and interventions for those with first-episode psychosis. This pioneering approach was initiated by the Seoul Mental Health Center, which established a community network, formed a clinical consortium with hospitals and clinics, and developed guidelines for early psychosis detection and management and for the Social Treatment for Early Psychosis (STEP) programme. The One-STEP programme, provided during hospitalisation, has been especially efficient in obtaining a high acceptance rate for community services. Several key issues are discussed with regard to the successful establishment of the close partnership between community mental health centres and hospitals / clinics.

Key words: Psychotic disorders / therapy; Social welfare

摘要

在首发思觉失调5年内提供密集式心理社会干预,是改善症状和功能的关键。近年,韩国的社区 精神复康中心把服务重心由慢性精神分裂症患者护理服务,转移为针对首发思觉失调患者的早 期检测和干预。这种崭新手法由韩国首尔精神健康中心创立,当中包括建立社区网络、医院和 诊所共同成立的临床团体,以及为早期思觉失调检测治疗和早期思觉失调社会治疗计划(简称 STEP)制定指引。在入院期间进行STEP第一阶段治疗,对患者重投社会的认受度尤其奏效。 本文也讨论社区精神健康中心与医院诊所间建立紧密关係的关键因素。

关键词:思觉失调/治疗、社会福利

Introduction

Late adolescence and early adulthood are critical stages of psychological, social, educational, and occupational development. Serious mental illness (e.g. psychosis) during these periods can lead to substantial disruption and subsequently to long-term functional disability and poor outcomes. Consequently, effective early therapeutic intervention that could prevent incipient biological, psychological, and social damage1,2 would merit worldwide attention. One year after treatment, 83 to 87% of first- episode psychosis patients achieve remission.3,4 However, 53.7% of first-episode psychosis patients relapse after 2 years, and 81.9% relapse after 5 years.5 Furthermore, suicide and other psychiatric crises are frequently reported in the early stages of psychosis.6 Although psychotic symptoms of first-episode psychosis can be relieved with medication, recovery of social and occupational functioning is still very difficult. A follow-up survey of first-episode psychosis patients showed that 47.2% of individuals achieved symptom remission after 5 years, but only 25.5% were able to maintain adequate social and occupational functioning for 2 years or longer.7 Thus, support from community services and intensive care within the 5-year critical period following the first psychotic episode is important for both symptomatic and functional recovery.

The psychiatric service utilisation rate among Korean patients with psychotic disorder is 21.4%,8 and the outpatient service utilisation rate 3 years after first admission is 42.8%.9 In Korea, hospitals do not use an active approach to promote continuous treatment among first-episode psychosis patients. Additionally, the community-wide management support system for first-episode psychosis patients is poorly structured. In a 2006 survey of 70 national community mental health centres (CMHCs), chronic mental illness management services were present in approximately 50% of these services; thus, early-psychosis community services are seldom provided.10 According to an early survey of the Seoul Mental Health Center (SMHC), only 1 to 5% of serious early-psychosis patients were registered. As a result, the focus on services for chronic mental illness and the lack of hospital referrals are considered the reasons for the denial of services to early-psychosis patients and for the absence of specific programmes.11 The referral rate from mental hospitals to CMHCs in Korea is very low — in 2010, the linkage rate between national mental hospitals and community service institutions was approximately 6.5%12; in 2008, the linkage rate of medical institutions with 25

Seoul-area CMHCs was about 7% among newly registered patients.11 A hospital-to-community linkage revitalisation project was established at the SMHC between 2005 and 2008; during this time, 1102 linkages were accomplished. However, among these, the referral rate for early psychosis did not exceed 6% (62 patients).

To overcome various problems relating to the management of first-episode psychosis, the SMHC initiated the first attempt to establish an early detection and intervention system in 2007. The next section discusses the development of the structural system and the Social Treatment for Early Psychosis (STEP) programme at the SMHC.

Early Intervention System for First-episode Psychosis in Seoul, Korea

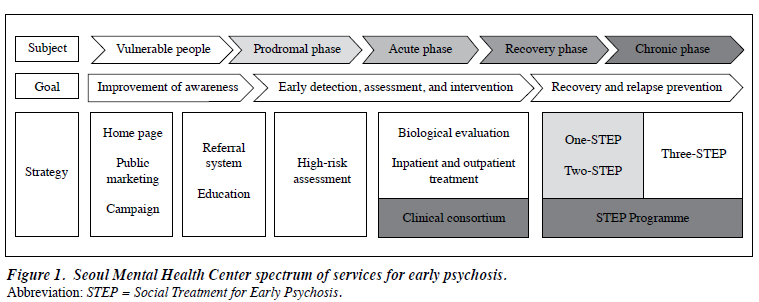

The main goals of an early intervention system were to improve awareness, provide high-risk group assessments, and offer a hospital-community continuum model for first- treated psychosis. The expected outcomes were reduced duration of untreated psychosis, increased treatment compliance, and reduced disease and social burden as a result of relapse prevention. The early psychosis project of the SMHC includes 5 parts (Fig 1):

- improving public awareness and promoting early detection and intervention;

- implementing a community-referral system for those at high risk for psychosis;

- developing a community-based assessment system for groups at high risk for psychosis;

- developing an interactive referral system for mental health organisations and the community; and

- providing a case management programme for first- treated psychosis, the STEP programme.

The SMHC provides various programmes to increase public awareness of early psychosis, as well as screening services and information about early psychosis through an online system (www.semis.or.kr). Establishing a community network incorporating university counselling centres, other medical sectors, and local CMHCs is an efficient strategy for improving early detection. The SMHC established guidelines for early-psychosis detection and management to facilitate cooperation within the community network. Additionally, active referrals from university and private hospitals, where most first-episode psychosis patients are treated, are critical to the success of an early intervention system. Therefore, the SMHC established a consortium with several university hospitals and private clinics showing interest in the early psychosis project. The SMHC categorises patients who seek help through an online system or are referred from hospitals into 4 groups and performs individualised assessments:

- group A: people who have problems with depression, anxiety, and similar conditions — providing counselling and, if necessary, referring them to appropriate facilities;

- group B: people who have prodromal symptoms — the SMHC refers them to consortium institutes for further evaluation and follow-up;

- group C: first-episode psychosis patients — to minimise the duration of untreated psychosis and provide appropriate treatment, the SMHC refers them to consortium hospitals; and

- group D: first-treated psychosis patients — to prevent relapse and promote community maintenance, the SMHC provides case management services.

The STEP programme was designed to provide a community-based service for patients with first-treated psychosis. The programme includes 3 parts. The One- STEP programme is a hospital-based programme that introduces community services to first-treated psychosis patients. The Two-STEP programme is an integration management programme for patients receiving their first treatment for psychosis who are introduced to the community. This programme is an intensive 18-month case management programme intended for first-treated psychosis patients between 14 and 29 years old. The Three-STEP programme includes programmes related to termination of case management and post-continuation services. This programme is provided based on patients’ clinical status and needs.

One-STEP: Programme Concept and Outcomes

Considering the Korean mental health environment, an active entry system operation for community management of first-treated psychosis patients seems to be very important. To facilitate referral of first-treated psychosis patients to community services, the One-STEP programme should be implemented in hospitals. We hypothesised that earlier contact during hospitalisation would reduce patients’ resistance and desire to hide their illness.

The One-STEP programme consists of 3 sessions (Fig 2). In the first session, the patients are shown a short animated DVD depicting the common early signs and symptoms experienced by patients with first-episode psychosis, such as mental confusion, perceptual abnormalities, and sensitive thoughts. Patients are then encouraged to express concerns, fears, and anxieties related to their first psychotic symptoms. The main purpose of this session is to normalise their experience and thereby reduce related trauma. The second session uses a 15-minute video to provide accurate information and education about first-episode psychosis and the importance of continuing treatment. The third session provides a 10-minute video related to the relapse crisis that might occur after discharge from hospital and provides useful information about mental health services that are available within the community. Each session lasts 30 to 50 minutes. The One-STEP programme provides patients with one-on-one care from SMHC staff members and treatment specialists from consortium hospitals. The following paragraph outlines the procedure used to obtain the community-service agreement.

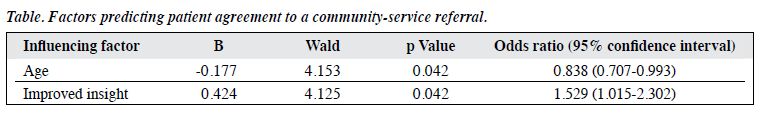

A total of 46 patients (25 men, 21 women) participated in the One-STEP programme for 18 months between July 2009 and December 2010. Their mean age was 25 years. In all, 43 patients (93%) were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 3 (7%) with bipolar disorder. Four patients (9%) had a family history of mental disorder, and 28 patients (61%) received treatment for less than 1 year. After the end of the One-STEP programme, 36 patients (78%) consented to a community mental health service referral, and the remaining 10 patients (22%) rejected the referral. To explore the factors predicting agreement to participate in the Two- and Three-STEP programmes, logistic regression was performed treating demographic characteristics (age and sex), diagnosis, family history, treatment duration, and change in scores on the Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire13 as independent variables. The results showed that improved insight and age were significant variables (unpublished data, Table).

Discussion

To facilitate the full recovery of patients with first- episode psychosis, it is essential to provide intensive and multidisciplinary care during the critical period. Typical examples are intensive intervention programmes such as those examined by the OPUS study (Denmark),14 Lambeth Early Onset Team (UK),15 and Prevention and Early Intervention Programme for Psychoses (Canada).16 One of the core features of these programmes is that hospitals are the primary facilities providing comprehensive services. This stands in contrast to the situation in Korea, where pharmacotherapy and case management, outreach, and crisis intervention are provided by completely different organisations (i.e. hospitals and CMHCs, respectively). The recent increasing interest in early psychosis by CMHCs in Korea is a unique trend, given that the role of CMHCs in western countries is limited primarily to providing services for those with chronic schizophrenia or a mental health disability.

Several issues must be addressed in the development of a multidisciplinary comprehensive psychosocial intervention by CMHCs in Korea. First, the settings / environments and locations of CMHCs must become brighter and more youth-friendly. In other words, the old, negative perception that a CMHC is a place where chronic, severely mentally disabled persons are being cared for should be eliminated as this has been a main deterrent to the referral of first-episode psychosis patients to CMHCs. Although seemingly impossible at present without government funding, the best strategy in this regard would be to open a separate CMHC targeting only early-psychosis patients. An alternative would be to operate 2 systems at different times (i.e. separate services for those with chronic and early psychosis in the mornings and afternoons, respectively). Second, it is important to foster active collaboration between hospitals and private clinics. It is also important to remember that a major deterrent to referring patients with first-treated psychosis to CMHCs is the negative image of CMHCs. To address this problem, CMHCs should develop a new high-quality programme appropriate for first-episode psychosis in addition to implementing structural reforms and undertaking efforts to educate hospitals and clinics about these innovations. Most importantly, patients with first-episode psychosis should have an initial contact with a social worker from a CMHC during their hospitalisation. In this way, possible resistance to the new service, which occurs frequently when the referral is made after discharge, could be minimised. This may explain the high acceptance rate of 78.3% among patients with first-episode psychosis in Seoul with respect to participation in community-based services after the One-STEP programme. Third, to meet the diverse needs of young people with psychosis, more novel, enjoyable, and high-level programmes should be developed to replace traditional services such as case management and day-care programmes. Lifestyle coaching, one of the services provided by the Jockey Club Early Psychosis Project in Hong Kong, may be a promising intervention in that people with schizophrenia often have poor health habits and are consequently at high risk for medical illnesses, especially obesity, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke.17,18 Interestingly, patients with schizophrenia (12%) and healthy people (16%) showed a significant increase in hippocampal volume after participating in an exercise programme, whereas the non-exercise group showed no significant changes in this regard (-1%).19 Substantial evidence points to the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy for first-episode psychosis.20-22 In general, the therapeutic components of cognitive behavioural therapy consist of psycho-education, coping training, cognitive reframing, and linking schema. The first 2 components are relatively easy and can be performed by community mental health workers if they are trained adequately. Finally, interventions to strengthen ego resilience may also be useful given that the first episode of psychosis offers the best window for recovery.

In summary, CMHCs in Korea are beginning to prepare themselves to provide new community services to patients with early psychosis. This pioneering move was initiated by the SMHC, which established a community network, formed a clinical consortium with hospitals and clinics, and developed guidelines for early-psychosis detection and management and for the STEP programme. The One-STEP programme, which is provided during hospitalisation, is especially efficient at obtaining a high acceptance rate for community services.

Declaration

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Funding sources have not played a role in any part of this research article.

References

- Birchwood M, Macmillan F. Early intervention in schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1993;27:374-8.

- McGorry PD. “A stitch in time”…the scope for preventive strategies in early psychosis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998;248:22-31.

- Lieberman J, Jody D, Geisler S, Alvir J, Loebel A, Szymanski S, et al. Time course and biologic correlates of treatment response in first- episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:369-76.

- Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, et al. Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:544-9.

- Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Bilder R, Goldman R, Geisler S, et al. Predictors of relapse following responses from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:241-7.

- Krausz M, Müller-Thomsen T, Haasen C. Suicide among schizophrenic adolescents in the long-term course of illness. Psychopathology 1995;28:95-103.

- Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM. Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:473-9.

- Cho MJ, Hahm BJ, Hong JP, editors. The epidemiological survey of psychiatric illnesses in Korea 2006. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2007.

- The structural causes and perpetuating factors affecting long-term hospitalization [in Korean]. National Human Rights Commission of Korea; 2008.

- Lee MS, Lee DW, Lee JY, Seo CH, Lee EJ. Service standard and performance indicator development for the community mental health center. A research project report of Management Center for Health Promotion; 2006.

- 1 Seoul Mental Health Center Annual Report [in Korean]; 2008. Website: http://www.blutouch.net. Accessed 13 Aug 2012.

- Seoul Mental Health Center Annual Report [in Korean]; 2010. Website: http://www.blutouch.net. Accessed 13 Aug 2012.

- Kim BY, Lee CW, Park CW. The relationship among insight, psychopathology and drug compliance in the schizophrenic patient. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 1993;32:373-80.

- Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Abel M, Kassow P, Petersen L, Thorup A, et al. OPUS study: suicidal behaviour, suicidal ideation and hopelessness among patients with first-episode psychosis. One-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2002;43:s98-106.

- Craig TK, Garety P, Power P, Rahaman N, Colbert S, Fornells- Ambrojo M, et al. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. BMJ 2004;329:1067.

- Addington J, Leriger E, Addington D. Symptom outcome 1 year after admission to an early psychosis program. Can J Psychiatry 2003;48:204-7.

- Roick C, Fritz-Wieacker A, Matschinger H, Heider D, Schindler J, Riedel-Heller S, et al. Health habits of patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007;42:268-76.

- Samele C, Patel M, Boydell J, Leese M, Wessely S, Murray R. Physical illness and lifestyle risk factors in people with their first presentation of psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007;42:117-24.

- Pajonk FG, Wobrock T, Gruber O, Scherk H, Berner D, Kaizl I, et al. Hippocampal plasticity in response to exercise in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:133-43.

- Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Killackey E, Bendall S, Allott K, Dudgeon P, et al. Acute-phase and 1-year follow-up results of a randomized controlled trial of CBT versus Befriending for first-episode psychosis: the ACE project. Psychol Med 2008;38:725-35.

- Lewis S, Tarrier N, Haddock G, Bentall R, Kinderman P, Kingdon D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy in early schizophrenia: acute-phase outcomes. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2002;43:S91-7.

- Tarrier N, Lewis S, Haddock G, Bentall R, Drake R, Kinderman P, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy in first-episode and early schizophrenia. 18-Month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2004;184:231-9.