East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2012;22:18-24

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

A Questionnaire Survey on Attitudes and Understanding towards Mental Disorders

对精神病的观念和了解问卷调查

萧慧敏、周洁云、林翠华、陈伟智、邓颖琦、崔永豪

Dr Bonnie Wei-Man Siu, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Kavin Kit-Wan Chow, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Prof Linda Chiu-Wa Lam, MD, FRCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Wai-Chi Chan, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, Shatin Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Victoria Wing-Kay Tang, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr William Wing-Ho Chui, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Bonnie Wei-Man Siu, Castle Peak Hospital, 15 Tsing Chung Koon Road, Tuen Mun, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 2456 7111; Fax: (852) 2463 1644; email: bonniew114m@yahoo.com

Submitted: 5 October 2011; Accepted: 8 November 2011

Abstract

Objectives: To obtain information about basic knowledge towards mental disorders and to evaluate public attitudes towards mental disorders in the Hong Kong Chinese population.

Methods: Questionnaires which collected basic demographic information, opinions about potential stigmas and myths, and knowledge on case vignettes depicting fictional characters with symptoms of mental illness were delivered to subjects in a secondary school, 2 homes for the elderly, a private housing estate, and a public housing estate in Hong Kong.

Results: Completed questionnaires were collected from 1035 subjects. In general, the participants’ acceptance of mental illness was good. Regular contacts with such patients were associated with better knowledge (t = –2.71, p < 0.01) and better acceptance (t = 2.77, p < 0.01) of mental illness. Younger participants aged 15 to 19 years had a lower level of knowledge about mental health problems compared with other age-groups (p < 0.001).

Conclusions: Personal contact with people with mental illness may help to improve knowledge and acceptance. Younger people in secondary school should be the target and prioritised group for mental health education. Apart from the delivery of mental health knowledge, strategies to increase social contact of the public with people having mental illness could be considered in the design and implementation of anti-stigma programmes.

Key words: Asian Continental Ancestry Group; Knowledge; Mental disorders; Social stigma

摘要

目的:了解香港人对精神病的基本观念和评估公众态度。

方法:在1所中学、2间护老院、1个私人屋苑和1个公共屋邨进行问卷调查,内容包括基本人口统计学资料、对潜在歧视和迷思的观点,以及面对有精神病症状的虚构人物情景时的处理方法。

结果:共收集1035份完整问卷。总体来说,被访者皆可接纳精神病患者。与患者有常规接触的与较清晰精神病观念(t = –2.71,p < 0.01)和较佳接纳度(t = 2.77,p < 0.01)呈相关。与其他年龄组别比较,15至19岁的被访者对精神病问题认识较少(p < 0.001)。

结论:与精神病患者接触有助改善观念和接纳程度,建议加强对在学青年相关教育。在推行教育的同时,於设计和推行消除歧视活动时也可考虑增加公众与精神病患者的接触机会。

关键词:亚洲大陆血统群、知识、精神病、社会歧视

Introduction

Stigma and discrimination associated with psychiatric illness have been evident for as long as such illness has existed.1 Despite the high prevalences of mental health problems, societies continue to hold deep-rooted, culturally sensitive, and often negative beliefs about mental illnesses.2,3 The consequences of stigma and discrimination are so pervasive that they affect the people with mental illness in every aspect of the life, and might also become the main impediment to rehabilitation and recovery.3 Because of the stigma and discrimination, people with mental illness encounter difficulties in obtaining housing, insurance, and employment.4,5 Their relatives and significant others may drift away resulting in social isolation. Social avoidance is common and various studies suggested that the general population may accept people with mental illness socially, but tend to withdraw from more personal relationships such as working or living together.1,6 As a result, people with mental illness face social isolation, social distance, unemployment, homelessness, and institutionalisation.3

Stigma and discrimination have direct implications for the prevention, early detection, treatment outcome, rehabilitation, and quality of life of people with mental illness, and indirectly affect the life of their significant others.7-11 Stigma acts as an obstacle to the presentation and treatment of mental illness at all stages, and brings about social exclusion.12 Social exclusion and the reduction of social networks could induce a worse outcome in chronic mental disorders.13 The adverse consequences of stigma on help-seeking behaviour and the disease outcomes have been further elaborated by Scheffer.14 In fact, the stigmatisation of mental illness and the lack of information on the symptoms of mental illness are seen as the main barriers to seeking help for mental health problems.

Over the last 50 years or so, stigma and discrimination have become even more significant owing to the trends of de- institutionalisation and the implementation of community mental health services.15 Negative public attitudes have become an essential factor in the management of mental illness since the beginning of the community mental health movement. People with mental illness can have a successful community reintegration only if the community environment is tolerant and supportive.7 Therefore, it is essential to evaluate and understand attitudes of the public towards people with mental disorders.

Studies of attitudes towards mental disorders are relatively scarce in the Chinese population, yet the existence of stigma and discrimination adhering to mental disorders cannot be denied.16-19 In the Chinese culture, some believe that mental illness is a punishment for the misdeeds of ancestors, the removal of spirits by shamanism, or the imbalance of the “Yin-Yang forces” inside the body and because of such beliefs, the stigmatisation and discrimination of mental illness might be more pronounced.20 Despite the fact that in the past few decades Hong Kong has developed into a modern city, some inhabitants still adhere to traditional practices and beliefs. This study set out to evaluate attitudes and stigma of a community sample of the general public towards mental disorders in Hong Kong. Their knowledge and understanding of mental disorders were also explored. The results of the study serve as the basis for the design and implementation of programmes to defeat stigma, and help in prioritising public programmes that should be targeted.

Methods

Participants

A convenience sample of Chinese participants aged 16 to 75 years was recruited from a secondary school, 2 homes for the elderly, a private housing estate, and a public housing estate in Hong Kong as well as through snowball method. Questionnaires that assessed attitudes and understanding towards mental disorders were delivered to all the students of the targeted school, all the residents of the homes for the elderly, and every household of the selected housing estate. The potential subjects were invited to participate in the survey by completing the questionnaire in 2 weeks and were asked to invite someone they knew to participate in the survey. The completed questionnaires were then collected by the investigators at these sites.

Measures

The questionnaire adopted in this survey had 3 parts. Part 1 collected basic demographic information including age, gender, number of years of education, frequency of contact with persons having mental illness, and whether the participants had any relatives suffering from mental illness. Part 2 enquired into their attitudes, potential stigmas and myths about mental disorders. This entailed a newly constructed 15-item scale developed with reference to previous research on stigma and discrimination3,12,16,21,22 and through expert panel discussions by psychiatrists, social workers, and psychologists. Part 3 assessed the knowledge of the participants by means of 2 case vignettes depicting fictional characters with symptoms of mental illness. The first described a 20-year-old introverted woman, being unemployed for 3 years and remaining idle at home and seldom contacting others. She presented with increased suspiciousness that she was being poisoned and monitored (a psychotic case). The second vignette described a middle- aged man, presenting with a 3-month history of distressed mood, deteriorating sleep and appetite with weight loss of more than 10 pounds, excessive self-blame, sense of worthlessness, social withdrawal, loss of interest, and suicidal ideation (a depressive case). The participants were asked to rate 5 items about each case vignette that related to their knowledge of mental illness. Each item in part 2 and part 3 was rated on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. An attitude (acceptance and stigma) score and a knowledge score were derived by adding the scores for the items in part 2 and part 3. The questionnaire was self-reported in nature and its completion was anonymous.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Windows version 17.0. Descriptive statistics were used for the analysis of the basic demographics and survey items of the questionnaire. Correlational analysis, t tests, and analysis of variance were used to explore the relationship between the demographic data and the attitude and the knowledge scores. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic Data and Ratings of Survey Items

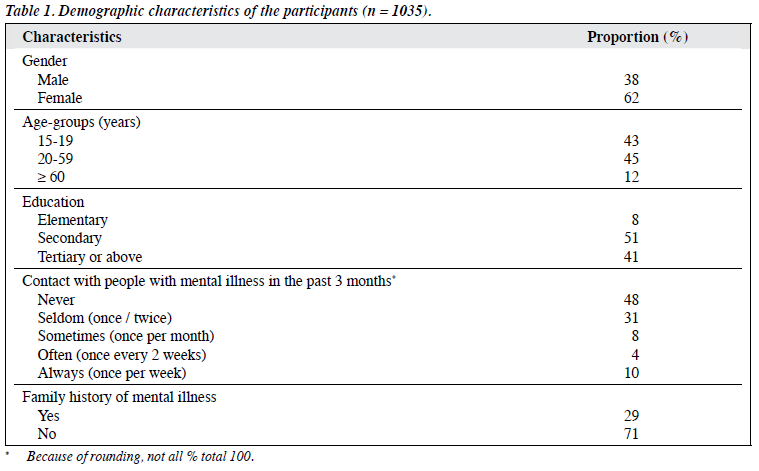

A total of 5000 questionnaires were delivered and 1035 completed questionnaires were collected, giving a response rate of 21%. The majority of participants were females (Table 1). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 32 (18) years, with a range of 15 to 102 years; the mean (SD) duration of education was 12 (4) years. About half (48%) of the participants never had any contact with persons with mental illness in the 3 months before the survey, whilst 10% of them had had contacts with such persons once per week. The majority (71%) did not have any relative suffering from mental illness.

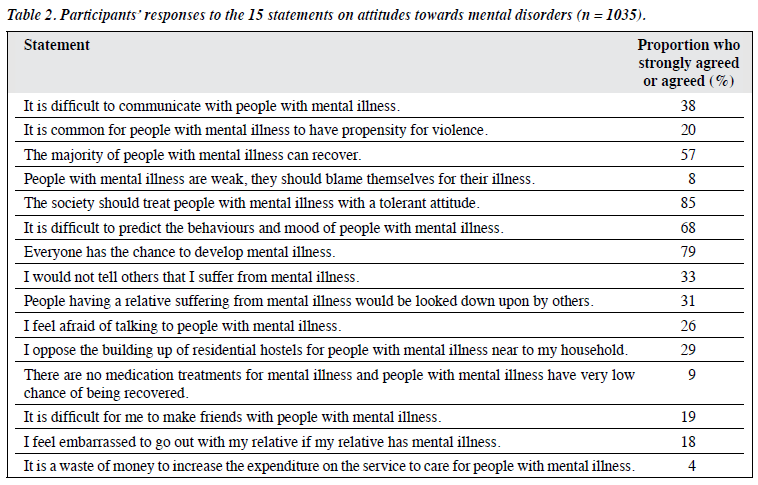

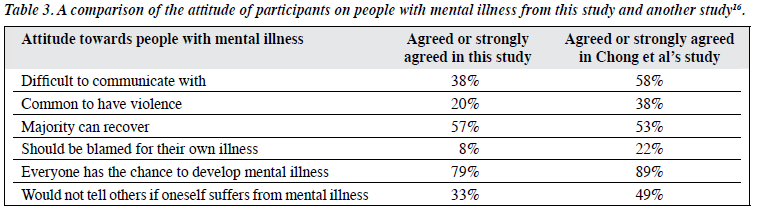

Table 2 shows the responses of the participants to each of the 15 questions on attitudes towards mental disorders. More than half (68%) agreed or strongly agreed that it was difficult to predict the behaviour and mood of people with mental illness, and more than one- third (38%) agreed or strongly agreed that it was difficult to communicate with people with mental illness. Also, 26% agreed or strongly agreed that he / she felt afraid of talking to persons with mental illness. One-fifth agreed or strongly agreed that it was common for people with mental illness to have a propensity to violence. One-third of the participants agreed or strongly agreed that he / she would not tell others if he / she suffered from mental illness. Less than one-tenth (8%) agreed or strongly agreed that people with mental illness were weak and should be blamed for their illness. The majority of the participants (85%) agreed or strongly agreed that society should treat people with mental illness with a tolerant attitude and that everyone had the chance to develop mental illness (79%). More than half of the participants (69%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that there were no medical treatments for mental illness and people with mental illness had a very low chance of recovering, and 51% did not feel embarrassed to go out with a relative if that person had mental illness. The majority (82%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that it was a waste of money to increase expenditure on the service to care for people with mental illness.

For the psychotic case scenario, the majority (91%) of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the subject was suffering from mental illness and the majority (82%) agreed or strongly agreed that the mental illness was very common and that it could be cured with medications and psychological treatments. However, around 10% of the participants agreed or strongly agreed that the patient was being disturbed by supernatural power.

For the depressive case scenario, the majority (87%) of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the patient was suffering from mental illness, whereas 20% agreed or strongly agreed that the subject did not have any major problems and was having a normal reaction to a setback in life. On the other hand, a minority (7%) agreed or strongly agreed that seeking help from mental health professionals would increase the suicidal risk of the subject, and 3% agreed or strongly agreed that the subject only needed to use hypnotics to help him sleep.

Relationship between Demographic Data and Ratings of Survey Items

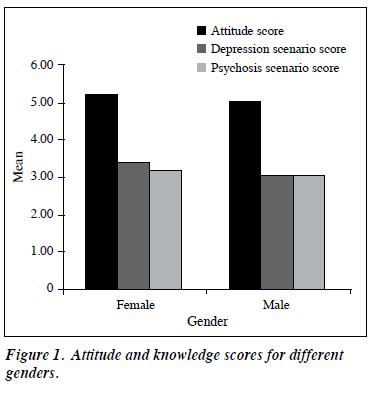

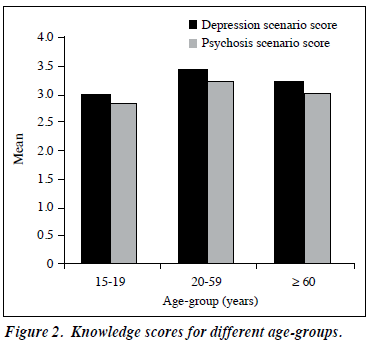

There were no gender differences in acceptance (p > 0.05) and women had higher scores concerning understanding of mental disorders (p < 0.05) [Fig 1]. Educational attainment was not associated with attitudes and knowledge (p > 0.05). Regular contacts (t = –2.71, p < 0.01) and the presence of family history of mental disorders (t = 2.70, p < 0.01) were associated with better knowledge in related problems. On the other hand, regular contacts (t = 2.77, p < 0.01) but not the presence of family history of mental illness (p > 0.05) were associated with better acceptance of mental illness. For persons aged 15 to 59 years, the acceptance towards mental health problems was higher than that in older participants (aged ≤ 60 years) [F = 6.38, p < 0.01]. For younger participants (aged 15-19 years), the knowledge level for mental health problems was lower than that of the other age-groups (p < 0.001) [Fig 2].

Discussion

Attitude and Knowledge of Mental Illness

Stigma and discrimination adhering to mental illness can adversely affect every aspect of the life of such a person and his / her significant others. They can bring about social exclusion, social distance, unemployment, housing problems, and can indirectly hinder the prevention, early detection, treatment, and prognosis of mental illness.7-10 They are the barriers to proper care and may even make the public less willing to pay for the care of people with mental illnesses, and contribute to the sense of hopelessness and low self-esteem of the sufferers.16,23 The stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness might be more prominent in Chinese populations because of the traditional beliefs on the causation of mental illness.16-19

In this study, the attitude (acceptance and stigma) towards mental illness by a group of Chinese recruited from the community was studied. Their knowledge on mental illness was also explored by 2 case vignettes. The participants in our study generally accepted mental illness well as the majority agreed or strongly agreed that society should treat people with mental illness in a tolerant way and that everyone had a chance of developing mental illness. The majority also disagreed or strongly disagreed that it was a waste of money to increase expenditure on services to care for people with mental illness. However, there was still a significant proportion of participants who agreed that it was difficult to communicate with people with mental illness. This was because they felt afraid to talk to such persons as they commonly believed the subjects had a propensity to violence and might not disclose their mental illness to others. When compared with results of a study by Chong et al16 on attitudes towards people with mental illness in an Asian community, our study participants had better acceptance of mental illness (Table 3). This might be explained by the over-representation of younger participants in our study and over-representation of older participants in the other study,16 with it being known that negative attitude towards mental illness correlated with an increasing age.16,24 Regarding the statements “I oppose the building up of residential hostels for people with mental illness near to my household” and “It is difficult for me to make friends with people with mental illness”, the majority of study participants rated “neutral” rather than overly agreeing or disagreeing. To a certain extent, these 2 statements assessed social distance. The results echo the findings of previous studies that the general population may accept people with mental illness socially, but tend to withdraw from more personal relationships such as working or living together.1,6,25 Despite the completion of the questionnaire according to the 5-point Likert response scale being anonymous, social desirability may lead the respondents to rate these 2 statements neutral.

The results of the 2 case vignettes in this study revealed that the majority of the participants did have the knowledge to appreciate that the 2 case subjects were possibly suffering from mental illness and that with treatment, the subjects could recover. However, for the psychotic case vignette, around 10% of the participants believed that the subject was disturbed by supernatural power, a percentage comparable to the 7.5% reported by Chong et al.16 For the depressive case vignette, one-fifth of the participants in our study believed that the subject did not have any major problems but only a normal reaction to setbacks in life. On the other hand, 7% of the participants believed that seeking help from mental health professionals would increase the risk of suicide. The reasons for such beliefs and their concerns about seeking help from mental health professionals need further exploration. Our findings reveal that the public needs more education on the causation and treatment of mental illness.

Association between Demographic Characteristics and Survey Items

In the study by Chou and Mak26 in Hong Kong, the views of the public on people with mental illness were found to be associated with their contacts with such people and their own socioeconomic status, age, and level of education, but not gender. Our study replicated some of their findings, that regular contact with persons with mental illness was associated with better knowledge and better acceptance of mental illness, as was younger age, but not gender. However, our study found no association between education and acceptance and knowledge. This could be due to under- representation of participants with low education levels in our study; in previous studies, low educational status has been associated with less acceptance and more stigma.16,26

A study by Lee et al17 on the stigma experienced by a group of Chinese suffering from schizophrenia provided evidence for the presence of familial ‘courtesy stigma’ and deliberate concealment. This revealed that stigma towards the patients from their family members and significant others is pervasive. In our study, the presence of family history of mental disorders was associated with better knowledge but not associated with better acceptance of mental illness, which echoed the results of Lee et al’s study.17 Nevertheless, in our study younger age was associated with better acceptance of mental illness, though the youngsters (15- to 19-year- old school kids) had less knowledge about mental health problems than other age-groups. These findings suggest that those with better knowledge of mental illness might not have better acceptance, which is in contrast with the findings of other studies on this issue.7,18 This might be due to the relatively high proportion (29%) of our participants having a family history of mental illness. In which case, they may have a better knowledge of mental illness because of a family member suffering from mental illness, even if they seldom come into contact with that person. Our results also suggest that the younger population should be targeted as a priority, when it comes to mental health education.

Programmes to Improve Mental Health Knowledge and Defeat Stigmatisation

Health care professionals have long faced the challenge of breaking down stigma and discrimination associated with mental health, and different researchers have different opinions on what strategies to use.21 Link27 mentioned that to achieve sustained stigma change, programmes must be multi-faceted and multi-level, and must address deeply held attitudes and beliefs that are the fundamental causes of stigma. Corrigan et al28 advocated a focus on protest, contact, and education. To reduce stigma, Chung and Wong18 suggested promoting contact between the public and individuals with mental illness as well as education to dispel misconceptions. Scheffer14 pointed out that the most effective strategies to defeat stigma were to create greater understanding and acceptance by means of a social marketing approach. Siu29 emphasised multi-level, multi- media mental health promotion programmes directed at the public as well as health care professionals other than those involved with mental health. Other researchers laid stress on the transmission of medical knowledge and the normalisation of media coverage about psychiatric patients.5,30,31

Programmes around the world are in place to reduce psychiatric stigma.32 The World Psychiatric Association embarked on a worldwide programme for patients with schizophrenia called “Open the Doors”, which aimed to increase awareness and knowledge on the nature of the disorder and treatment options, with a view to improve public attitudes towards affected patients and their families. There were programmes specifically designed for young people as the latter tended to be more enlightened, humanitarian, and scientific in their understanding.21,24,33 Pinfold et al21 described the effectiveness of short educational workshops that included components of ‘mental health promotion and education’ and ‘contact’ that were directed at improving young participants’ attitudes towards people with mental health problems. The workshops were supported by information leaflets produced specifically for young people and implemented in 2 phases. Phase 1 consisted of mental health awareness workshops delivered by a facilitator working in the field of mental health. In phase 2, the sessions were co-facilitated by a person who had personal experiences of living with mental health problems.21 In our study, younger people (aged 15-19 years) had the lowest knowledge about mental health, so mental health education directed at secondary school students may have a far- reaching impact on enhancing corresponding literacy in the community. A programme similar to that of Pinfold et al21 could also be adopted for Hong Kong students.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

One limitation of our study was that participants were recruited from only 1 school, 2 elderly homes, 1 public housing estate, and 1 private housing estate. Thus ours was a non-random, convenience sample whose results may not be generalised to the population of Hong Kong. Our sample was also over-represented by younger persons, and hence did not reflect the age-group distribution of the Hong Kong population.34 Moreover, the response rate was low (21%) and the demographics of those who did not respond were not obtained for comparison. Non-respondents may be more prone to stigmatise than respondents. Our self-reporting survey questionnaire was designed based on previous research on stigma by an expert panel after discussion of the psychometric properties of the questionnaire, but it was not tested. Despite completion of the questionnaire being anonymous, the 5-point Likert response scale as well as social desirable pressure may have motivated participants who agreed or disagreed with items to select neutral responses. Moreover, this was a cross-sectional study and associations between the variables were observed as simultaneous measures, so no conclusions could be drawn on causal relationships.

As suggested by Lee et al,17 in future a large-scale survey on stigmas with a random community sample could be considered; the subjective experiences of everyday stigmas of people with mental illness and their significant others could be further explored. Moreover, the psychometric properties of the survey questionnaire should be tested.

Conclusion

Despite culturally embedded beliefs, in general the Hong Kong Chinese participants in this study accepted mental illness well. Further education on the causation and treatment of mental disorders for the public is necessary. Personal contact with people with mental illness may help to improve acceptance. Younger people in secondary schools should be the target group prioritised for mental health education. Apart from the delivery of mental health knowledge, strategies should aim to increase social contact with persons having mental illness. Such measures could be considered in an attempt to overcome stigmas and discrimination in the community.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants of this community survey. We would also like to thank Mr David Lee for his assistance in the conduct of this study. The authors declare that there is no financial support and no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- Bhugra D. Attitudes towards mental illness. A review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;80:1-12.

- Fabrega H. Psychiatric stigma in non-Western societies. Compr Psychiatry 1991;32:534-51.

- World Psychiatric Association. The WPA global programme to reduce the stigma and discrimination because of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia — open the doors training manual. Geneva: World Psychiatric Association; 2005.

- Read J, Baker S. Not just sticks and stones: a survey of stigma, taboos and discrimination experienced by people with mental health problems. London: Mind Publishing; 1996.

- Hayward P, Bright JA. Stigma and mental illness: a review and critique. J Ment Health 1997;6:345-50.

- Rabkin JG. Public attitudes toward mental illness: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull 1974;10:9-33.

- Stuart H, Arboleda-Flórez J. Community attitudes toward people with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 2001;46:245-52.

- Malla A, Shaw T. Attitudes towards mental illness: the influence of education and experience. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1987;33:33-41.

- Rosenfield S. Labeling mental illness: the effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. Am Soc Rev 1997;62:660- 72.

- Mechanic D, McAlpine D, Rosenfield S, Davis D. Effects of illness attribution and depression on the quality of life among persons with serious mental illness. Soc Sci Med 1994;39:155-64.

- 1 Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Harmondsworth: Pelican Books; 1968.

- Byrne P. Stigma of mental illness and ways of diminishing it. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2000;6:66-72.

- Brugha TS, Wing JK, Brewin CR, MacCarthy B, Lesage A. The relationship of social network deficits with deficits in social functioning in long-term psychiatric disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1993;28:218-24.

- Scheffer R. Addressing stigma: increasing public understanding of mental illness. Toronto, Canada: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2003.

- Test MA, Stein LI. Alternative to mental hospital treatment. III. Social cost. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980;37:409-12.

- Chong SA, Verma S, Vaingankar JA, Chan YH, Wong LY, Heng BH. Perception of the public towards the mentally ill in a developed Asian country. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007;42:734-39.

- Lee S, Lee MT, Chiu MY, Kleinman A. Experience of social stigma by people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:153-7.

- Chung KF, Wong MC. Experience of stigma among Chinese mental health patients in Hong Kong. Psychiatr Bull 2004;28:451-4.

- Found A, Duarte C. Attitudes to mental illness: the effects of labels and symptoms. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2011;21:91-8.

- Wong DF, Tsui HK, Pearson V, Chen E, Chiu ES. Changing health beliefs on causations of mental illness and their impacts on family burdens and the mental health of Chinese caregivers in Hong Kong. Int J Ment Health 2003;32:84-98.

- Pinfold V, Toulmin H, Thornicroft G, Huxley P, Farmer P, Graham T. Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:342-46.

- Byrne P. Psychiatric stigma. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:281-4.

- A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 1999.

- D’Arcy C. Opened ranks? Blackfoot revisited. In: Coburn D, D’Arcy C, Torrance GM, New P, editors. Health and Canadian society. 2nd ed. Richmond Hill, ON: Fitzhenry and Whiteside; 1987: 280-94.

- Lawrie SM. Stigmatisation of psychiatric disorder. Psychiatr Bull 1999;23:129-31.

- Chou KL, Mak KY. Attitudes to mental patients among Hong Kong Chinese: a trend study over two years. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1998;44:215-24.

- Link BG. Stigma: many mechanisms require multifaceted responses. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2001;10:8-11.

- Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, Penn DL, Uphoff-Wasowski K, Campion J, et al. Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophr Bull 2001;27:187-95.

- Siu BW. Mental health promotion in Hong Kong: a way to prevent stigmatization and enhance the early intervention of mental illness. Hong Kong J Ment Health 2011;37:17-21.

- Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. Am Psychol 1999;54:765-76.

- Crisp A. The tendency to stigmatise. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:197-9.

- World Psychiatric Association. The WPA global programme to reduce stigma and discrimination because of schizophrenia. Volumes 1-5. Geneva: World Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Bailey S. Young people, mental illness and stigmatisation. Psychiatr Bull 1999;23:107-10.

- Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR Government. Mid-year population estimates 2010. Hong Kong SAR Government Printing Department; 2010.