East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2014;24:156-164

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

药物依赖程度量表於华籍氯胺酮滥用而寻求治疗者的可靠性和 有效性评估

董梓光、杨诗咏、蒋天宝、许珂、林明

Dr Chi-Kwong Tung, MBChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Alcohol and Drug Dependence Unit, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Sze-Wing Yeung, MBChB, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Alcohol and Drug Dependence Unit, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Tin-Po Chiang, MBBS, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Alcohol and Drug Dependence Unit, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Ke Xu, MD, PhD, MSc, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, United States.

Dr Ming Lam, MBChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Alcohol and Drug Dependence Unit, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Chi-Kwong Tung, Alcohol and Drug Dependence Unit, Castle Peak Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 2456 7111; Email: ricky.cktung@gmail.com

Submitted: 17 July 2014; Accepted: 27 August 2014

Abstract

Objective: Despite growing popularity of ketamine misuse in Asia, there is a lack of a validated instrument to measure the severity of ketamine dependence. Psychometric properties of Chinese Severity of Dependence Scale for ketamine (C-SDS-K) were examined in a sample of treatment-seeking ketamine users in Hong Kong.

Methods: A total of 80 treatment-seeking ketamine users were recruited from 3 treatment centres. The C-SDS-K was administered to assess their severity of dependence on ketamine in the previous month. The diagnosis of their ketamine misuse as per the DSM-IV criteria, and the count of dependence criteria fulfilled in the previous month were determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I).

Results: The C-SDS-K showed high internal consistency (α = 0.74) and test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.95). Total score of C-SDS-K correlated positively with frequency (rs = 0.73, p < 0.001) and dose (rs = 0.89, p < 0.001) of ketamine use per week in the previous month, duration of regular ketamine use (rs = 0.28, p = 0.01), and the count of DSM-IV ketamine dependence criteria met in the previous month (rs = 0.84, p < 0.001). All items loaded strongly on a single factor (factor loading ≥ 0.60) in principal component analysis.

Conclusion: The findings support SDS as a reliable and valid tool for measuring the severity of dependence in the treatment-seeking population of Chinese ketamine users.

Key words: Ketamine; Substance-related disorders; Treatment outcome

摘要

目的:儘管氯胺酮滥用在亚洲日益普及,但仍缺乏一个衡量氯胺酮依赖重度的有效工具。本文检视用作评估寻求治疗的华籍氯胺酮滥用者的药物依赖程度量表(SDS)中文版其心理测量特性。

方法:从叁间治疗中心纳入80名寻求治疗的华籍氯胺酮滥用者,并使用SDS评估他们过去一个月对氯胺酮的依赖程度。研究以SCID-I评定根据DSM-IV标準诊断的氯胺酮滥用,以及过去一个月依赖次数的标準。

结果:SDS表现高的内部一致性(α = 0.74)和重测信度(内相关系数 = 0.95)。SDS总分与下列项目呈正相关,包括过去一个月每週使用氯胺酮次数(rs = 0.73,p < 0.001)和剂量(rs = 0.89,p < 0.001)、经常滥用氯胺酮的持续时间(rs = 0.28,p = 0.01),以及过去一个月根据DSM-IV氯胺酮药物依赖标準的滥药次数(rs = 0.84,p < 0.001)。所有项目都负载於主成分分析的单一因子上(因子载荷≥ 0.60)。

结论:研究结果认同SDS是评估寻求治疗的华籍氯胺酮滥用者其药物依赖程度的可靠工具。

关键词:氯胺酮、药物关联疾患、治疗结果

Introduction

Ketamine is a non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist developed as an anaesthetic in 1962.1 Manufactured under the trade name “Ketalar”, ketamine has found its place within several areas of medicine.2 However, its propensity to produce “emergence phenomenon” in patients recovering from ketamine anaesthesia, characterised by delusion, hallucination, delirium and mind-body dissociation, has prevented it from becoming a mainstream anaesthetic. Ironically, these adverse effects that limit ketamine’s medical use have paved its way to non-medical use.3 Recreational drug users value it for the dream-like hallucinations, floating sensations, perceptions of increased efficiency and creativity, feelings of arousal and euphoria, as well as the mystical experiences of self- transcendence.4

Soon after ketamine was developed, its illegal manufacture, distribution, and misuse were reported in the West Coast of the United States.5 Some have suggested that it may have been linked to veterans returning from Vietnam War who had experienced it on the field.6 Until the 1980s, ketamine misuse was mainly restricted to North America, being linked to groups of individuals who were most often involved in the medical field.7,8 In the 1990s, ketamine gained mass popularity among young drug users with the global rise of dance-club culture.9,10 Along with MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine, or known as the “ecstasy”), ketamine became a new addition to the thriving “poly-pharmacy” of dance scene drug use.11

The escalation in popularity of ketamine misuse in Hong Kong is probably unmatched internationally. In fact, it is deemed the single most abused psychotropic drug in Hong Kong according to data from Central Registry of Drug Abuse, which documents drug users who come into contact with authorities and health care professionals. In the past decade, ketamine has been the most commonly used psychotropic drug in Hong Kong, more than doubling the figure of second-placed amphetamines (31.5% vs. 14.0% in the year 2011).12 The percentage of ketamine use in reported drug users aged under 21 years reached 85% by 2008, which implied that vast majority of emerging young drug users in the city were using ketamine.12

Dominance of ketamine misuse in Hong Kong is also reflected by its burden on the local health care system. Ketamine users represented 16% of all drug users attending the Accident and Emergency Departments of all public hospitals in 2005; the proportion rose to 40% in 2008.13 Hong Kong is among the few places in the world, where newly recognised medical conditions associated with chronic ketamine misuse were being identified and reported in the medical literature, including ketamine-induced cystitis14,15 and ketamine-induced cholangiopathy.16

Despite the wide range of physical, mental, and cognitive adverse effects associated with ketamine misuse,17,18 so far there is a poverty of medical research on ketamine dependence, limiting to reports of individual cases only.19-23 One of the reasons may be lack of a validated instrument for the objective assessment of ketamine dependence.

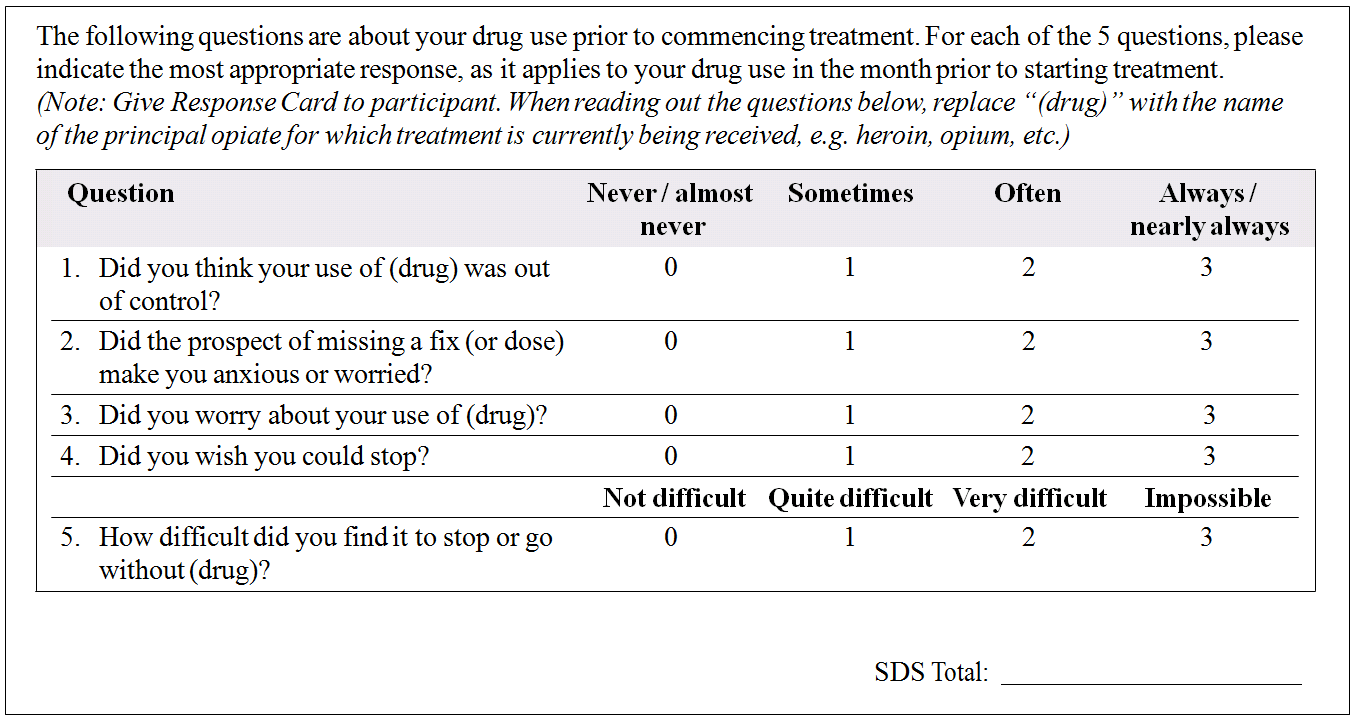

The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) [Appendix 1] is one of the most widely used instruments for measuring drug dependence in research and clinical setting.24,25 It is a self-rated questionnaire containing 5 items which are explicitly concerned with psychological components of the dependence construct. Wording of the instrument can be adapted to cover different types of drugs and variable time frame. The merits of SDS lie on its brevity and ease of comprehensibility, which can be completed within minutes with no requirement of trained personnel.

The SDS has established its validity and reliability across a diversity of major drugs of misuse including heroin, amphetamine, cocaine,24,26 cannabis,27-29 and benzodiazepines.30 Its usefulness has also been tested in other drugs like MDMA31 and khat.32

The SDS has been translated into multiple languages and it has demonstrated good cross-cultural adaptability in its Chinese version.33-35 There has been attempt to use SDS for measurement of severity of dependence on “club drugs” as a whole, which includes ketamine.36 However, the validity and reliability of SDS on primary ketamine users have yet to be formally validated.

The present study therefore aimed at investigating the validity and reliability of SDS in measuring severity of dependence on ketamine in a population of treatment- seeking Chinese ketamine users. A validated instrument to assess ketamine dependence may provide foundation for future studies on ketamine misuse. This may serve as an important clinical correlate and an objective index of the severity of ketamine use problem in an individual. It may be potentially useful in monitoring changes among ketamine users in cohort studies37 and evaluation of treatment outcome.38

Methods

Participants

A total of 80 ketamine users were recruited in the present study, who were attending treatment at a hospital-based drug misuse treatment clinic and 2 community-based counselling centres for psychotropic drug users in the New Territories West of Hong Kong, from October 2011 to July 2012. To meet the inclusion criteria, they had to be ≥ 18 years old, able to read and complete self-report questionnaire in Chinese, and using ketamine at least once per month in the previous 6 months. This definition has been used in previous validation studies of SDS.31,39 Co-morbid psychiatric disorders or misuse of drugs other than ketamine did not exclude them from enrolment.

Procedures

Ethics approval for the present study was obtained from the Clinical and Research Ethics Committee, New Territories West Cluster, Hong Kong Hospital Authority.

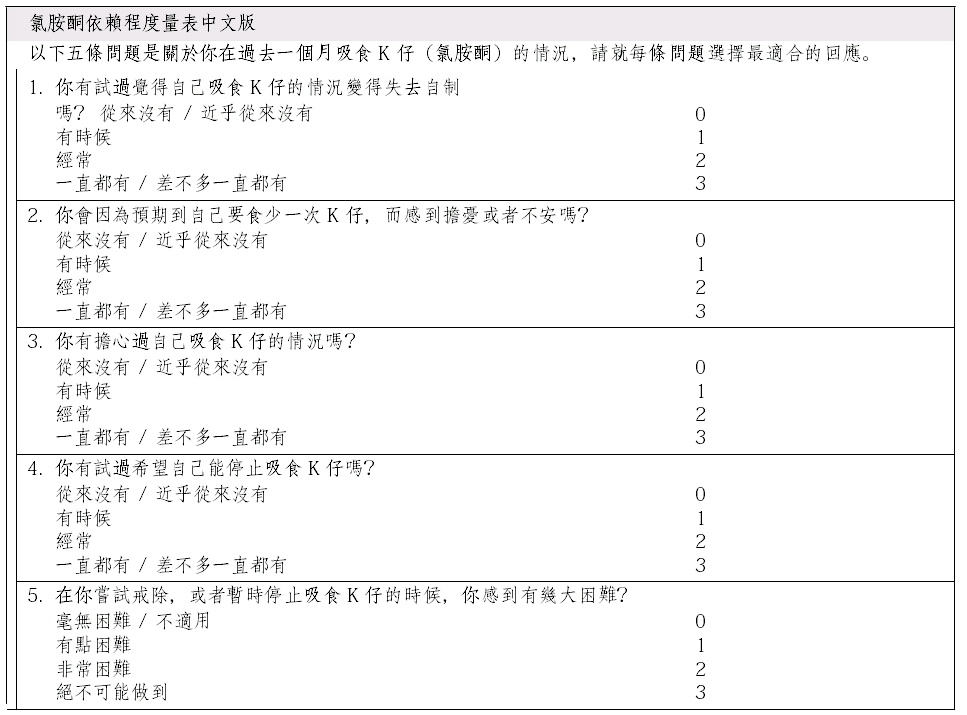

The Chinese Severity of Dependence Scale for ketamine (C-SDS-K) was developed from its English version24 (Appendix 2). The SDS was first translated into Chinese and independently back-translated to English. The 2 versions were then compared by an expert panel to ensure satisfactory validity of translation and content validity.

The 5 items in the C-SDS-K included: (1) “Did you think your use of ketamine was out of control?”; (2) “Did the prospect of missing a dose of ketamine make you anxious or worried?”; (3) “Did you worry about your use of ketamine?”; (4) “Did you wish you could stop?”; and (5) “How difficult did you find to stop or go without ketamine?” Each item was scored on a 4-point scale (0: never / almost never; 1: sometimes; 2: often; 3: always / nearly always for items 1-4; and 0: not difficult; 1: quite difficult; 2: very difficult; 3: impossible for item 5), giving a total score ranging from 0 to 15. Higher total score indicated more severe dependence on ketamine.

Face-to-face interviews with the recruited participants were conducted at the premises of their treatment centres, or other public areas where they usually met their case workers. They were fully briefed on the nature and purpose of the study, as well as their right to withdraw from the study at any time if they wished. Confidentiality and anonymity of information supplied were emphasised. They were recruited into this study after signing a written informed consent.

Participants were asked to complete the self-rated C- SDS-K, which concerned their experience and behaviour with reference to ketamine use in the previous month. This time frame was chosen as it would be more difficult for participants to accurately report their ketamine use behaviour spanning a longer period of time. It also matched the definition of a current diagnosis of ketamine dependence in the DSM-IV criteria, which requires ≥ 3 dependence criteria to be met in the previous month.40

The DSM-IV diagnosis concerning participants’ ketamine use, and the count of diagnostic criteria for ketamine dependence fulfilled in the previous month were determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) administered by a trained psychiatrist. Information on socio-demographic data and their drug use parameters was collected by a structured questionnaire.

A consecutive sample of 24 participants was selected for the assessment of test-retest reliability of C-SDS- K. They completed C-SDS-K again a week after the first interview; the second interview was preferably conducted at the same location and roughly at the same time of the day in order to minimise any external influence that might affect reporting. The 1-week interval was set to reduce memory effect of the participants, while at the same time avoiding any significant change in the severity of their dependence on ketamine.

Upon the completion of study procedure, each participant was reimbursed with a shopping voucher valued at HK$100 (about US$13).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 20.0 for Windows. All analyses were 2- tailed; significance level was set at p values of < 0.05 throughout the study. Descriptive statistics were generated using the data of subjects’ demographic information and characteristics of drug use. Internal consistency was assessed by Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, while test-retest reliability was determined by intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Concurrent validity was examined by the linear correlation coefficients between total score of C-SDS-K and the count of DSM-IV ketamine dependence criteria met in the previous month as identified by the SCID-I. Similarly, correlation between total score of C-SDS-K and parameters of ketamine use, including days of ketamine use per week, dose of ketamine use per week, and duration of regular ketamine use (defined as using ketamine ≥ 3 times per week) were also assessed. Factor structure of C-SDS-K was assessed by principal component analysis (PCA); factor with eigenvalue of > 1 was retained.

Results

Characteristics of Participants

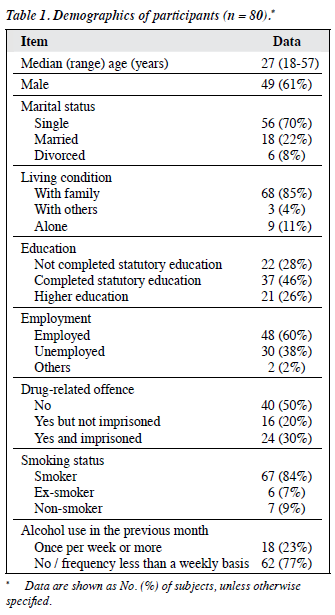

Demographics of the participants are summarised in Table 1. The majority of participants were young and unmarried. The male-to-female ratio was about 3:2. Most of them (84%) were current smokers. Only 23% had used alcohol once per week or more in the previous month.

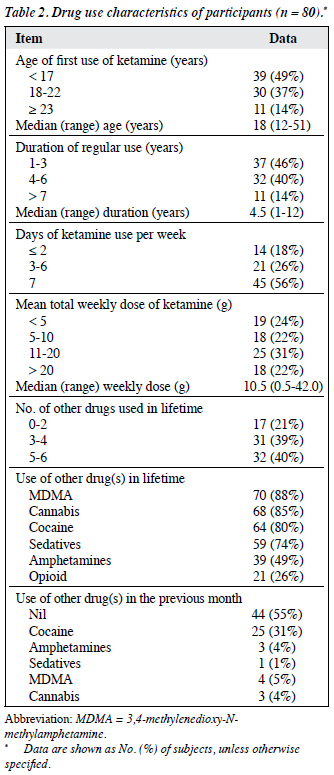

Drug Use Other Than Ketamine

In their lifetime, on average, they had had experience with 4 illicit drugs other than ketamine, the most common drugs being MDMA (88%) followed by cannabis (85%) and cocaine (80%). In the previous month, over half of the participants (55%) used ketamine only; while 31% had used cocaine on top of ketamine during this period (Table 2).

Pattern of Ketamine Use

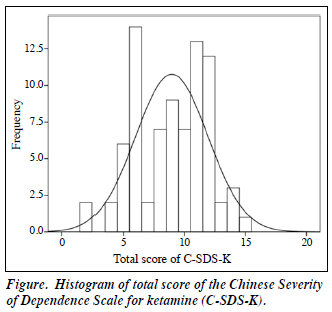

All participants used ketamine by intranasal route only. The median age of their first use of ketamine was 18 (range, 12-51) years. The median duration of regular ketamine use was 4.5 (range, 1-12) years. Current daily users constituted 56% of the sample. The median ketamine consumption per week was 10.5 (range, 0.5-42) grams. Distribution pattern of the total score of C-SDS-K is shown in the Figure. The median total score was 9 (mean 8.96, range 2-15). Of these 80 participants, 77 (96%) had received a lifetime diagnosis of ketamine dependence obtained by the SCID-I, in which 54 (68%) of them met the criteria of a current diagnosis of ketamine dependence, i.e. having ≥ 3 dependence criteria met in the previous month.

Reliability

The internal consistency of the C-SDS-K as measured by Cronbach’s coefficient alpha was 0.74. Test-retest reliability derived from 24 participants was determined by ICC, which was 0.95 (95% confidence interval = 0.88-0.98) for the total score of C-SDS-K. The ICCs for the 5 individual items were 0.80, 0.85, 0.75, 0.77 and 0.79, respectively.

Concurrent Validity

There were positive correlations between the total score of C-SDS-K and the count of ketamine dependence diagnostic criteria met in the previous month (rs = 0.84, p < 0.001), the dose of ketamine consumed per week (rs = 0.89, p < 0.001), the number of days of ketamine use per week (rs = 0.73, p < 0.001), and the duration of regular ketamine use (rs = 0.28, p = 0.01).

Factor Structure

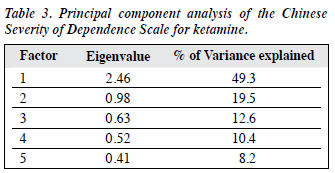

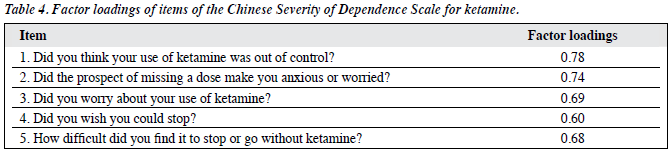

The PCA was performed on the 5 items of C-SDS-K to determine the factor structure. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy yielded a value of 0.73, indicating that this sample was suitable for PCA (> 0.50). A single- factor solution was revealed, which accounted for 49.3% of the variance (Table 3). The component matrix (Table 4) showed that all items loaded strongly on this single factor (all ≥ 0.60).

Discussion

The results confirm that C-SDS-K is a valid and reliable instrument to measure severity of ketamine dependence in a treatment-seeking population of Chinese ketamine users. The high value of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha reflected that all 5 items in C-SDS-K were highly consistent in measuring the same construct of psychological dependence on ketamine, whereas the high test-retest reliability showed its stability across time. Positive correlations between total score of C-SDS-K and indices of ketamine use severity, including frequency of ketamine use, dose and duration of regular use, indicated its good concurrent validity. The validity of C-SDS-K was further strengthened by strong correlation between its total score and the count of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ketamine dependence met in the previous month. Data from the DSM-IV field trials showed that when using a criterion count method to assess severity, it correlated well with associated problems with dependence on different drug classes.41

The PCA revealed a single-factor structure with all items loading strongly on it, providing further evidence for the unidimensional structure of SDS.42 It also hinted that the unifactorial structure of dependence construct might be applicable to ketamine, as in the cases of cocaine, opiates, and cannabis.43

These findings are consistent with the results of previous validation studies for SDS in different types of drugs in the western countries, suggesting that the concept of drug dependence as assessed by the SDS has cross-cultural validity.34 The SDS’s focus on the psychological component of dependence instead of physiological withdrawal may also make it particularly suitable for use in ketamine, as ketamine is capable of producing strong craving in its frequent user.11,44 while existence of a specific ketamine withdrawal syndrome remains controversial.10

The non-randomised sampling and relatively small sample size in the present study mean the representativeness of this sample to the wider ketamine-using community cannot be assessed. Caution is advised when results of this study are to be generalised to ketamine users from other subgroups or general population. This treatment-seeking population may be different from the non–treatment- seeking counterparts in terms of severity of physical, mental, and social problems they are facing, level of psychosocial distress, and motivation to change.45 This is reflected in several characteristics in the sample, including significant unemployment rate (38%), school failure (28% failed to complete statutory education in Hong Kong, which is equivalent to grade 8 in the United States), and high prevalence of drug-related offense (50%).

Other limitations include reporting bias due to social desirability, although anonymity and privacy were guaranteed, and this applies to all risk behaviour–related studies. The trained psychiatrist who administered SCID-I was not blinded to the score of C-SDS-K. Observer bias was minimised by leaving C-SDS-K to the end of assessment. Thus, result of SCID-I was not influenced by the score of C-SDS-K. Self-report drug use data were not independently verified, for example, by laboratory analysis of ketamine concentration in hair samples.46 However, literature review has demonstrated respectable reliability and validity of self- report data on drug use behaviour, when compared with biomarkers, criminal records, and collateral interviews.47

Conclusion

The findings of this study support C-SDS-K as a reliable and valid instrument to measure severity of dependence in the treatment-seeking Chinese ketamine users. Its brevity and low cost of administration should encourage its application in both research and clinical settings.

Declaration

The authors declared no conflict of interests for this study.

References

- Domino EF, Chodoff P, Corssen G. Pharmacologic effects of Ci-581, a new dissociative anesthetic, in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1965;6:279-91.

- Morgan CJ, Curran HV; Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. Ketamine use: a review. Addiction 2012;107:27-38.

- Wolff K, Winstock AR. Ketamine: from medicine to misuse. CNS Drugs 2006;20:199-218.

- Jansen KL. A review of the nonmedical use of ketamine: use, users and consequences. J Psychoactive Drugs 2000;32:419-33.

- Lankenau SE, Clatts MC. Drug injection practices among high-risk youths: the first shot of ketamine. J Urban Health 2004;81:232-48.

- Dillon P, Copeland J, Jansen K. Patterns of use and harms associated with non-medical ketamine use. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003;69:23-8.

- Ahmed SN, Petchkovsky L. Abuse of ketamine. Br J Psychiatry 1980;137:303.

- Kamaya H, Krishna PR. Ketamine addiction. Anesthesiology 1987;67:861-2.

- Reynaud-Maurupt C, Bello PY, Akoka S, Toufik A. Characteristics and behaviors of ketamine users in France in 2003. J Psychoactive Drugs 2007;39:1-11.

- Jansen KL, Darracot-Cankovic R. The nonmedical use of ketamine, part two: A review of problem use and dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs 2001;33:151-8.

- 1 Muetzelfeldt L, Kamboj SK, Rees H, Taylor J, Morgan CJ, Curran HV. Journey through the K-hole: phenomenological aspects of ketamine use. Drug Alcohol Depend 2008;95:219-29.

- Narcotics Division, Security Bureau, HKSAR Government. Central Registry of Drug Abuse Hong Kong SAR. Central Registry of Drug Abuse Sixty-first Report; 2012.

- Ng SH, Tse ML, Ng HW, Lau FL. Emergency department presentation of ketamine abusers in Hong Kong: a review of 233 cases. Hong Kong Med J 2010;16:6-11.

- Chu PS, Ma WK, Wong SC, Chu RW, Cheng CH, Wong S, et al. The destruction of the lower urinary tract by ketamine abuse: a new syndrome? BJU Int 2008;102:1616-22.

- Yiu MK, Ng CM, Ma WK, To KC. The prevalence and natural history of urinary symptoms among recreational ketamine users. BJU Int 2012;110:E164-5.

- Seto WK, Ng M, Chan P, Ng IO, Cheung SC, Hung IF, et al. Ketamine-induced cholangiopathy: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1004-5.

- Corazza O, Assi S, Schifano F. From “Special K” to “Special M”: the evolution of the recreational use of ketamine and methoxetamine. CNS Neurosci Ther 2013;19:454-60.

- Kalsi SS, Wood DM, Dargan PI. The epidemiology and patterns of acute and chronic toxicity associated with recreational ketamine use. Emerg Health Threats J 2011;4:7107.

- Critchlow DG. A case of ketamine dependence with discontinuation symptoms. Addiction 2006;101:1212-3.

- Lim DK. Ketamine associated psychedelic effects and dependence. Singapore Med J 2003;44:31-4.

- Pal HR, Berry N, Kumar R, Ray R. Ketamine dependence. Anaesth Intensive Care 2002;30:382-4.

- Hurt PH, Ritchie EC. A case of ketamine dependence. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:779.

- Moore NN, Bostwick JM. Ketamine dependence in anesthesia providers. Psychosomatics 1999;40:356-9.

- Gossop M, Darke S, Griffiths P, Hando J, Powis B, Hall W, et al. The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS): psychometric properties of the SDS in English and Australian samples of heroin, cocaine and amphetamine users. Addiction 1995;90:607-14.

- Gossop M, Best D, Marsden J, Strang J. Test-retest reliability of the Severity of Dependence Scale. Addiction 1997;92:353.

- González-Sáiz F, Domingo-Salvany A, Barrio G, Sánchez-Niubó A, Brugal MT, de la Fuente L, et al. Severity of dependence scale as a diagnostic tool for heroin and cocaine dependence. Eur Addict Res 2009;15:87-93.

- van der Pol P, Liebregts N, de Graaf R, Korf DJ, van den Brink W, van Laar M. Reliability and validity of the Severity of Dependence Scale for detecting cannabis dependence in frequent cannabis users. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2013;22:138-43.

- Hides L, Dawe S, Young RM, Kavanagh DJ. The reliability and validity of the Severity of Dependence Scale for detecting cannabis dependence in psychosis. Addiction 2007;102:35-40.

- Martin G, Copeland J, Gates P, Gilmour S. The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) in an adolescent population of cannabis users: reliability, validity and diagnostic cut-off. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;83:90-3.

- de las Cuevas C, Sanz EJ, de la Fuente JA, Padilla J, Berenguer JC. The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) as screening test for benzodiazepine dependence: SDS validation study. Addiction 2000;95:245-50.

- Bruno R, Matthews AJ, Topp L, Degenhardt L, Gomez R, Dunn M. Can the severity of dependence scale be usefully applied to ‘ecstasy’? Neuropsychobiology 2009;60:137-47.

- Kassim S, Islam S, Croucher R. Validity and reliability of a Severity of Dependence Scale for khat (SDS-khat). J Ethnopharmacol 2010;132:570-7.

- Gu J, Lau JT, Chen H, Liu Z, Lei Z, Li Z, et al. Validation of the Chinese version of the Opiate Addiction Severity Inventory (OASI) and the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) in non-institutionalized heroin users in China. Addict Behav 2008;33:725-41.

- Chen VC, Chen H, Lin TY, Chou HH, Lai TJ, Ferri CP, et al. Severity of heroin dependence in Taiwan: reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS[Ch]). Addict Behav 2008;33:1590-3.

- Tsai JH, Tang TC, Yeh YC, Yang YH, Yeung TH, Wang SY, et al. The Chinese version of the Severity of Dependence Scale as a screening tool for benzodiazepine dependence in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2012;28:225-30.

- Ding Y, He N, Shoptaw S, Gao M, Detels R. Severity of club drug dependence and perceived need for treatment among a sample of adult club drug users in Shanghai, China. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:395-404.

- Bloor M, Neale J, Weir C, Robertson M, McKeganey N. Severity of drug dependence does not predict changes in drug users’ behaviour over time. Crit Public Health 2008;18:381-9.

- Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, Kidd T. The National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS): 4-5 year follow-up results. Addiction 2003;98:291-303.

- Topp L, Mattick RP. Choosing a cut-off on the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) for amphetamine users. Addiction 1997;92:839-45.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

- Woody GE, Cottler LB, Cacciola J. Severity of dependence: data from the DSM-IV field trials. Addiction 1993;88:1573-9.

- Gonzalez-Saiz F, Lozano OM, Ballesta R, Silva T, Brugal MT, Bilbao I, et al. Validity of the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) construct applying the item response theory to a non-clinical sample of heroin users. Subst Use Misuse 2008;43:919-35.

- Hasin DS. Combining abuse and dependence in DSM-5. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2012;73:702-4.

- Morgan CJ, Rees H, Curran HV. Attentional bias to incentive stimuli in frequent ketamine users. Psychol Med 2008;38:1331-40.

- Hser YI, Maglione M, Polinsky ML, Anglin MD. Predicting drug treatment entry among treatment-seeking individuals. J Sub Abuse Treat 1998;15:213-20.

- Lee VW, Cheng JY, Cheung ST, Wong YC, Sin DW. The first international proficiency test on ketamine and norketamine in hair. Forensic Sci Int 2012;219:272-7.

- Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998;51:253-63.

Appendix 1. Severity of Dependence Scale.

Appendix 2. Chinese Severity of Dependence Scale for Ketamine (C-SDS-K).