East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:16-20

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

吴睿颖、陈友凯

Dr Joanne Yui-Wing Ng, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Prof. Eric Yu-Hai Chen, MD(Edin), MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Prof. Eric Yu-Hai Chen, Head of Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 2855 4488; Fax: (852) 2855 1345; Email: eyhchen@hku.hk

Submitted: 24 June 2014; Accepted: 4 November 2014

Abstract

Objectives: The historical evolution of the existing terms used to describe insanity may be able to shed light on the formation of stigma towards psychosis patients. In Hong Kong, a widely used Cantonese term for insanity ‘Chi Sin’ (黐線) provides a unique example because of its neutral original sense, as it literally means misconnection in a network circuit. We attempt to trace the origin and subsequent evolution of the term ‘Chi Sin’ from its early use to the present day to understand how local Hong Kong people have attached increasingly negative connotations to this scientific term since the mid-20th century.

Methods: We sampled as many newspapers and magazines published in Hong Kong from 1939 to June 2014 as possible, and sampled 7 popular local movies from the 1950s and 1960s. We also searched all the newspapers published in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and Mainland China from January 1998 to June 2014, and searched several other local historical resources.

Results: In one early use of ‘Chi Sin’ in 1939, the term was only used in a technical sense to describe ‘short circuiting’. We found that the development of the telephone system, the Strowger system, in Hong Kong is closely related to the evolution of the semantics of the term ‘Chi Sin’.

Conclusions: The original meaning of short circuitry of the term ‘Chi Sin’ is no longer used, and it has become a dead metaphor through repeated use with negative emotional connotations. This illustrates some of the factors facilitating the emergence of a metaphor with subsequent semantic drift.

Key words: Psychotic disorders; Schizophrenia; Semantics; Social stigma

摘要目的:现有关於形容精神错乱的字词,其语义的历史演变或与社会对精神病患者的偏见相关。在香港,一个被广泛使用的广东词「黐线」为典型例子,这个中性词的字面意思原为电线短路。本文尝试追踪「黐线」的使用起源和後续演进,从而了解香港社会如何自20世纪中把这个 科学术语推进至越加负面的含意。 方法:从1939年到2014年6月出版的报刊以及50、60年代7部热门电影进行采样,并且由1998年1月至2014年6月於香港、澳门、台湾和中国大陆出版的报纸以及其他本地历史资料库 中进行资料搜集。

结果:「黐线」一词源於1939年,当时只是一个技术词语,意指电线短路。研究发现电话系统Strowger的发展与「黐线」的语义演变密切相关。

结论:「黐线」一词的本义已不再使用,随著重複使用於负面的涵义上,这字词已变成一个亡隐喻。这说明有些因素能导致隐喻的语义转移。

关键词:精神病患、精神分裂症、语义、社会歧视

Introduction

Stigma and discrimination against mental illnesses are severe in spite of the high prevalence of psychiatric diseases around the world. Societies still hold deep-rooted negative attitudes towards mental health problems. Many studies have suggested that the general population may intellectually accept people with mental illness, but tend to withdraw from closer relationships, for instance, when 16 © 2015 Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists working or living together.1,2 People with mental health problems continue to face multiple difficulties ranging from social isolation and unemployment to homelessness and institutionalisation.3

The Chinese term for psychosis ‘Yan Zhong Jing Shen Bing’ (嚴重精神病) literally means ‘serious mental diseases’ and carries strongly negative attitudes and considerable stigma.4,5 The stigma linked to the naming of mental illnesses have proven to have immense negative impact on patients.6 Mental health professionals have proposed changes to the naming of serious mental illnesses, especially, schizophrenia.7,8 In both Hong Kong and a number of Asian countries that use a character-based writing system,9 the stigma caused by traditional naming for schizophrenia has been highly detrimental. New names for schizophrenia or psychosis have been introduced and adopted by mental health professionals. In Hong Kong, the more accurate and informative term ‘Si Jue Shi Tiao’ (思 覺失調), which literally means ‘dysregulation of thought and perception’, has been used to replace the old term for psychosis.10 The effectiveness of this change and the long- term fate of new terms for psychosis are being studied. In this context, it is important to review the historical evolution of existing terms used to describe insanity in popular culture. In Hong Kong, a widely used Cantonese term for insanity ‘Chi Sin’ (黐線) provides a uniquely informative example because of the relatively neutral original sense of the term ‘Chi Sin’, which literally means misconnection in a network circuit.

Understanding the early use of the term ‘Chi Sin’ and its subsequent evolution would be of paramount importance to understanding how local Hong Kong people have attached increasingly negative connotations to this scientific term since the mid-20th century. We attempted to trace the origin and subsequent evolution of the term ‘Chi Sin’ from its early use to the current time.

Methods

Newspapers, Magazines, and Comics

Regarding media sources, we tried to sample as many newspapers and magazines published since the late 1930s to June 2014 as possible through the micro-film format at the Hong Kong Central Library, The University of Hong Kong (HKU), Hong Kong Public Libraries, and Hong Kong newspaper clippings online of the HKU Libraries.11 We have also searched all the newspapers in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and Mainland China published since January 1998 to June 2014 via WiseNews database via HKU Library subscription.12

Movies and Other Local Historical Resources

We conveniently sampled 7 popular local movies from the 1950s and 1960s. We also searched Hong Kong Oral History Archives of the HKU,13 Hong Kong Oral History Collection of the Hong Kong Public Libraries,14 the online exhibitions of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government

Records Service,15 and the Hong Kong Literature Database of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.16

Efforts were also made to trace the radio programmes from the 1930s, but the availability of these resources was limited. We also tried to trace television programmes from the late 1950s and early 1960s (the first television station in Hong Kong was established in 1957).

Results and Discussions

Pre-existing Terms Describing Insanity Used in Hong Kong

In the popular language of Hong Kong, insanity is commonly described in Cantonese as ‘Chi Sin’ (黐線), ‘Jing Sun Beng’ (精神病), ‘Fat Sun Ging’ (發神經), ‘Fung’ (瘋), and ‘Fung Din’ (瘋癲). The terms ‘Sun Ging Beng’ (神經病) and ‘Din’ (癲) were commonly used to describe mental illnesses in local newspapers in the 1930s.

The First Appearance of ‘Chi Sin’ as a Technical Term

One early use of the term ‘Chi Sin’ is an article published on 17 June 1939 in the local newspaper The Chinese Mail (《香港華字日報》).17 The term was used in the article to describe technical circuitry problems of an air raid siren leading to a false alarm, and was not used to describe human behaviours. This may imply that in the year 1939 or earlier, the term ‘Chi Sin’ was only used in a technical sense to describe ‘short circuiting’.

How did ‘Chi Sin’ Evolve from a Technical Term to Describing Human Behaviours?

Development of the telephone system in Hong Kong is of paramount importance in understanding the evolution of the semantics of the term ‘Chi Sin’. Being connected to the wrong telephone number, i.e. ‘connected to the wrong line’ (搭錯線) apparently was the transitional semantic link between short circuitry and insanity. In this context, it is important to briefly review the history of the telephone system in Hong Kong.

‘Chi Sin’ and Phone Misconnection

Prior to modern digital telephone systems, the dial-based Strowger system used in Hong Kong until 1991 had certain intrinsic error rates resulting in a call being misconnected to a wrong telephone. When the selector got stuck at a particular position, there was no warning or alarm so the maintenance personnel would not know about the error unless there were customer complaints. The technicians would then have to carry out manual ‘clouting’ to clean the selector. For example, if the final selector got stuck on the telephone number 654321, all numbers from 654320 to 654329 would be directed to 654321, meaning that if the selector of 1 digit became stuck then all the telephone numbers of 1 to 9 would be defaulted to the number 1. The error rates rose exponentially as the number of exchange lines increased.

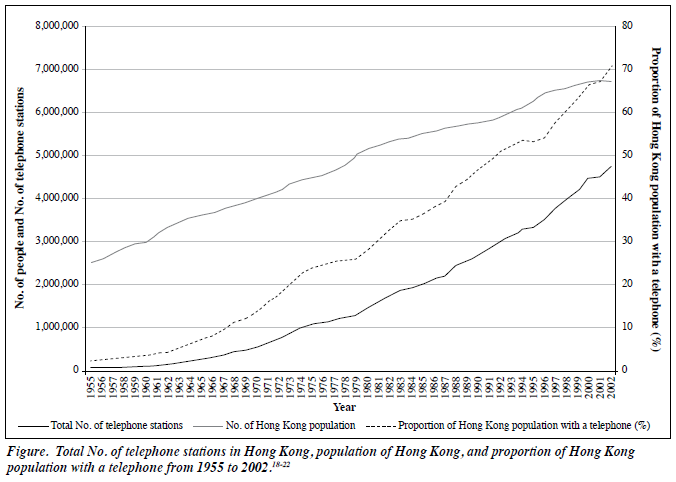

The total number of telephone lines in Hong Kong from 1955 to 2001 are listed in the Figure. We noticed there was a dramatic surge in the number of telephone lines from the mid-1950s and the early 1960s.18 It can be seen that, along with population growth, the proportion of Hong Kong people with telephone lines rapidly increased from 1% in the 1940s and the 1950s to around 20% in the 1970s.18-22 This made the experience of telephone misconnection commonplace as evident in the wrong connection jokes23 in the news24 in the 1950s and the 1960s. Below is a typical joke from the 1960s25,26:

Mr A: “Hello, are you Mr B?”

Mr B: “Yes.”

Mr A: “Can I borrow $500 from you?”

Mr B: “Sure.”

Mr A: “Sorry I have a mis-connected call (搭錯線).”

Mr A hung up the phone and said to himself that no way Mr B could agree to lend me money.

This experience of having a misconnected phone call set the context for the semantic transformation of the term ‘Chi Sin’ from the previous technical sense to the new sense of telephone misconnection.

As the telephone services became more common in the 1960s and the Hong Kong population also grew rapidly, the term ‘Chi Sin’ was much more commonly used and became popular among the Hong Kong population. People started using the term to describe patients with mental illnesses and psychosis, including auditory hallucinations, bizarre delusions, and other behavioural disturbances.27,28

The Establishment of the Term ‘Chi Sin’ to Describe Insanity in the 1960s

An earliest use of ‘Chi Sin’ to describe insanity was in an article published on 24 April 1964 in the Chinese Student Weekly (《中國學生周報》) with the content: “Telephone service charges have been raised. Crazy?” (the word ‘crazy’ here is used in the sense of not understandable, absurd behaviour).29

In another article published on 8 May 1964, also in the Chinese Student Weekly, the term ‘Chi Sin’ was used in the sense of craziness as a condition and an illness, “... some readers deliberately sent letters to condemn you and irritate you which is mental mistreatment to you, in the long term, you may become ‘insane’, in the worst case you may even die due to the anger.” (「……有D讀者專寫信來鬧你, 激你,無形中係精神虐待啫,長此以往,容乜易黐線 架,嚴重D嚟講重會激死人添噃。」).30 Here the sense of a diagnosable disorder is becoming evident.

The health column of the local magazine Companion (《伴侶》) on 16 August 1964 clearly illustrated different types of psychosis and described insanity as ‘Chi Sin’.31 In the article, it is written that “Recently four ‘insane’ people (referring to the Beatles who visited Hong Kong on 9 June 1964) from the United Kingdom came to Hong Kong and had attracted much attention of young people here… Insanity is a condition that occurs in youth. If people with traits of ‘Chi Sin’ know that one can become famed by being insane, there may be a risk of triggering an epidemic of insanity.” (「最近香港也鬧了一陣狂人迷,四個英 國狂人來到香港,引得好些青年男女如醉如痴……狂 人病本來是青春期最易發生的精神分裂病。平日若早 有若干「黐線」的表現的人,一旦發覺有人以狂出名 而 且 週 遊 世 界 , 就 更 難 免 一 觸 即 發 , 大 癲 大 廢 起 來 了。」)

Another early use of ‘Chi Sin’ as ‘insanity’ was in an article published on 21 October 1964 in the Overseas Chinese Daily News (《華僑日報》): a man who exposed himself in public claimed that he was ‘Chi Sin’ and was willing to be examined by psychiatrists.32 This is the first medicolegal context in which the term was used. It seems clear that, by this time, the term had been firmly established as a popular term for the description of insanity. Subsequently, the term has been widely used for this purpose, to the present day, to an extent that the original meaning of short circuiting is seldom assessed.

In the late 1960s, the metaphorical sense of the term ‘Chi Sin’ with the technical meaning of circuit disconnection was still present — in an article published on 26 June 1969 in Ta Kung Pao (《大公報》), it was written that a computer expert had difficulty finding a job, thus “his brain had gone insane” and he stabbed himself to death with a knife.33

The Strowger telephone system was gradually phased out and was completely replaced by the current digital system in the early 1990s. Telephone misconnection is exceedingly rare nowadays. Yet the term ‘Chi Sin’ has stayed.

Conclusions

In contemporary Hong Kong Cantonese, the exclusive meaning of ‘Chi Sin’ is insanity. It is used in a derogatory, scornful sense. The original meaning of ‘short circuitry’ is no longer accessed, despite the fact that it turns out to be rather close to contemporary neuroscience formulations of psychotic disorders as ‘disconnection syndrome’ or ‘brain network dysfunction’.34-37 However, owing to historical mistiming, this potentially effective term has become a dead metaphor through repeated use with negative emotional connotations.38-47 In tracing the historical evolution of the term ‘Chi Sin’, we witness a vivid example of a term being transformed from a pure technical term to one that is used to denote insanity, and that has accrued many negative associations throughout its life. The example illustrates some of the factors facilitating the emergence of a metaphor, with subsequent semantic drift. Whether with increasing knowledge of the outcome of ‘names of insanity’, it may be possible to propose strategies for a more managed evolution of such terms to minimise stigma is a question that demands further study.

Declaration

The authors declared that there was no financial support for this article and the research work, and no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- Bhugra D. Attitudes towards mental illness. A review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;80:1-12.

- Rabkin JG. Public attitudes toward mental illness: a review of the literature. Schizophr Bull 1974;10:9-33.

- World Psychiatric Association. The WPA global programme to reduce the stigma and discrimination because of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia — open the doors. Training manual (September 2005). Available from: http://www.open-the-doors.com/english/media/Training_8.15.05.pdf.Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- Lee S, Lee MT, Chiu MY, Kleinman A. Experience of social stigma by people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:153-7.

- Chung KF, Wong MC. Experience of stigma among Chinese mental health patients in Hong Kong. Psychiatr Bull 2004;28:451-4.

- Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol 2004;59:614-25.

- Ono Y, Satsumi Y, Kim Y, Iwadate T, Moriyama K, Nakane Y, et al. Schizophrenia: is it time to replace the term? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999;53:335-41.

- Levin T. Schizophrenia should be renamed to help educate patients and the public. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2006;52:324-31.

- Kim Y, Berrios GE. Impact of the term schizophrenia on the culture of ideograph: the Japanese experience. Shizophr Bull 2001;27:181-5.

- Wong GH, Hui CL, Chiu CP, Lam M, Chung DW, Tso S, et al. Early detection and intervention of psychosis in Hong Kong: experience of a population-based intervention programme. Clin Neuropsychiatry 2008;5:286-9.

- Hong Kong newspaper clippings online of the HKU Libraries. Available from: http://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/ER/detail/hkul/2197636

- WiseNews database. Available from: here.

- The Hong Kong Oral History Archives Project, the Centre of Asian Studies and Department of Sociology, the University of Hong Kong. Available from: http://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkoh.

- Hong Kong Oral History Collection of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Available from: http://www.hkpl.gov.hk/en/thematic/ohi/index.html.

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government Records Service. Available from: http://www.grs.gov.hk/ws/english/home.htm.

- Hong Kong Literature Database, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Available from: http://hklitpub.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/index_eng.jsp.

- 香港仔突來空襲警報 原來係警報機黐線 附近居民飽吃虛驚 (An air raid siren went ‘Chi Sin’ leading to false alarm) [in Chinese]. The Chinese Mail 1939 Jun 17; Sect. 2:4. Available from the Multimedia Information System of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- Hong Kong Economic History Database, Hong Kong Institute for Monetary Research (HKIMR). Available from: http://www.hkimr.org/ content-id20. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- Hambro EI. The problem of Chinese refugees in Hong Kong; Report submitted to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Leyden: AW Sijthoff; 1955.

- Chiu TN. The port of Hong Kong: a survey of its development. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 1973.

- Manion M. Corruption by design: building clean government in Mainland China and Hong Kong. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2004.

- Mitchell BR. International Historical Statistics: Africa, Asia and Oceania, 1750-2005. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2007.

- 居士, 電話風雲集 [in Chinese].《中國學生周報》第816期 (1968年 3月8日), 第8版. Available from: http://hklitpub.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/pdf/ journal/78/1968/216945p.pdf. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 電話公司賺大錢 電話卻經常黐線 (Telephone companies have made great profits but the telephone services always go ‘Chi Sin’) [in Chinese]. Ta Kung Pao 1968 Mar 14; Sect. 2:5. Available from the Multimedia Information System of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 恩, 電話集 [in Chinese].《中國學生周報》第816期 (1968年3月 8日), 第8版. Available from: http://hklitpub.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/pdf/journal/78/1968/216946p.pdf . Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 弓長張, 黐線記 [in Chinese].《學生叢書》第19期 (1969年3 月), 第50頁. Available from: http://hklitpub.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/pdf/journal/92/1969/274207.pdf . Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 德明夜中‧翠綠, 黐線 [in Chinese].《中國學生周報》第649期 (1964年12月25日), 第8版. Available from: http://hklitpub.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/pdf/journal/78/1964/205161p.pdf. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 小離, 喜歡奧圖怪 [in Chinese].《中國學生周報》第659期 (1965年 3月5日), 第11版. Available from: http://hklitpub.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/pdf/journal/78/1965/205864p.pdf . Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 海楓‧燕, 電話公司加價,黐線? (Telephone service providers increase charges, ‘Chi Sin’?) [in Chinese].《中國學生周報》第614 期 (1964年4月24日), 第12版. Available from: http://hklitpub.lib. cuhk.edu.hk/pdf/journal/78/1964/202946p.pdf. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 新孫子兵法, 一哀二駡三撒嬌 四諦五恐嚇 [in Chinese].《中國學 生周報》第616期(1964年5月8日), 第12版. Available from: http://hklitpub.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/pdf/journal/78/1964/203046.pdf. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 莊綺, 狂人迷與青春病 (Fans of insanity and the disease of the youth – schizophrenia) [in Chinese].《伴侶》第40期 (1964年8月 16日), 第21頁. Available from: http://hklitpub.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/pdf/journal/29/1964/580838.pdf . Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 莊洪當街暴露下體向兩少女作自瀆狀 向法庭自稱黐線願入院受 檢驗 (A man exposed himself in public, claimed himself is ‘Chi Sin’ and is willing to be examined by psychiatrists) [in Chinese]. Overseas Chinese Daily News 1964 Oct 21; Sect. 2:2. Available from the Multimedia Information System of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 電腦專家求職難 人腦黐線自斬死 (A computer expert who had difficulties in finding a job went “‘Chi Sin’ in his brain” and stabbed himself to death) [in Chinese]. Ta Kung Pao 1969 Jun 26; Sect. 1:4. Available from the Multimedia Information System of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- Rubinov M, Bullmore E. Schizophrenia and abnormal brain network hubs. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2013;15:339-49.

- Liu H, Kaneko Y, Ouyang X, Li L, Hao Y, Chen EY, et al. Schizophrenic patients and their unaffected siblings share increased resting-state connectivity in the task-negative network but not its anticorrelated task-positive network. Schizophr Bull 2012;38:285-94.

- Stephan KE, Friston KJ, Frith CD. Dysconnection in schizophrenia: from abnormal synaptic plasticity to failures of self-monitoring. Schizophr Bull 2009;35:509-27.

- Andreasen NC, Paradiso S, O’Leary DS. “Cognitive dysmetria” as an integrative theory of schizophrenia: a dysfunction in cortical- subcortical-cerebellar circuitry? Schizophr Bull 1998;24:203-18.

- 死者暴躁常打被告 且時外宿有些黐線 (The victim was always irritable, often beat the defendant, frequently lives at other places and is ‘Chi Sin’) [in Chinese]. The Kung Sheung Daily News 1968 Oct 23; p.6. Available from the Multimedia Information System of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 升中試害人佐證 少女讀書讀到黐線 昨突跳樓幸受篷阻 (A young girl went ‘Chi Sin’ because studied too hard for the Secondary School Entrance Examination and attempted suicide by jumping from height) [in Chinese]. Ta Kung Pao 1969 Oct 8; Sect. 2:5. Available from the Multimedia Information System of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 躲入廁所 呆若木雞 書院學生咪書咪到黐線 (A high school student studied too hard and went “Chi Sin”, hiding in the toilet in catatonic stupor) [in Chinese]. Ta Kung Pao 1968 Oct 11; Sect. 1:3. Available from the Multimedia Information System of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 醫務處精神病專科主任透露 黐線求診者增多 股市投機會引致 精神病 (Officers at psychiatry clinic reveal the number of ‘Chi Sin’ patients has been increasing and claims that investing in stock market will lead to psychiatric illnesses) [in Chinese]. Ta Kung Pao 1969 Oct 8; Sect. 2:5. Available from the Multimedia Information System of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 澳青年不堪被叫黐線仔 昨用菜刀割頸自殺重傷 (A Macau young man could not bear to be called “‘Chi Sin’ guy” so he cuts his own neck with a kitchen knife resulting in serious injury) [in Chinese]. Ta Kung Pao 1988 Jan 7; Sect. 2:5. Available from the Multimedia Information System of the Hong Kong Public Libraries. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

- 穿心刀殺妻 兇手疑黐線 (A man who murdered his wife by stabbing her in the heart was suspected to be ‘Chi Sin’) [in Chinese]. Wen Wei Po 2005 May 8; Sect. A:18.

- 弒母狂漢頻呼:「阿媽黐線」(A man who murdered his mother keeps yelling his mother is ‘Chi Sin’) [in Chinese]. Sing Tao Daily 2006 Mar 27; Sect. A:21.

- 一萬精神病患者獨居舊區 何喜華憶失常舅自殺亡 籲多關懷 (Over 10,000 patients with psychiatric illnesses live alone in the old districts in Hong Kong. Social activist Ho Hei-wah recalls his uncle who had psychiatric illness committed suicide and he encourages citizens to care patients with psychiatric illnesses more) [in Chinese]. Hong Kong Economic Times 2007 Apr 10; Sect. A:29.

- 林依麗叫對手「黐線科醫生」(Lam Yi-lai, an independent candidate of Kowloon West constituency of Legislative Council, called her rival who is a psychiatrist as “a doctor of ‘Chi Sin’ specialty”) [in Chinese]. Ming Pao 2012 Aug 20; Sect. A:18.

- 大鬧白雲機場黐線女失控 (A ‘Chi Sin’ woman was out of control at Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport) [in Chinese]. Hong Kong Commercial Daily 2013 Jul 27; Sect. A:13.