Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2009;19:72-7

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

尼日利亞醫學院學生對精神醫學的態度

Dr BA Issa, Department of Behavioural Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, PMB 1515, Ilorin, 240001, Nigeria.

Dr OA Adegunloye, Department of Behavioural Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, PMB 1515, Ilorin, 240001, Nigeria.

Dr AD Yussuf, Department of Behavioural Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, PMB 1515, Ilorin, 240001, Nigeria.

Dr OA Oyewole, Department of Psychiatry, College of Health Sciences, LAUTECH, Osogbo, Nigeria.

Dr FO Fatoye, Department of Mental Health, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Address for correspondence: Dr BA Issa, Department of Behavioural Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, PMB 1515, Ilorin, 240001, Nigeria.

Tel: (234) 8033559293;

E-mail: issababa2002@yahoo.com

Submitted: 27 August 2008; Accepted: 11 November 2008

Abstract

Objective: To report attitudes to psychiatry before and after their psychiatric posting, among final-year medical students of a Nigerian University using the 30-item Attitude To Psychiatry questionnaire.

Participants and Methods: A total of 126 students participated pre-clerkship, while 135 students participated in the post-clerkship phase of the study.

Results: Approximately 54% of the students scored above the Attitude To Psychiatry questionnaire midpoint (90) at the pre-clerkship assessment, while 41% of the students scored higher than 90 at the post-clerkship phase. The mean (± standard deviation) score also decreased significantly (p = 0.03) from 90.6 (± 9.4) pre-posting to 88.2 (± 8.2) at the end. Facets that showed appreciable decline were those that evaluated the teaching of the subject, symptom worry being made worse by treatment, and perceived job satisfaction of psychiatrists by the students.

Conclusion: The general attitude to psychiatry of this group of medical students witnessed an unfavourable trend after psychiatric exposure. Some of the areas that need to be improved upon undergraduate teaching in psychiatry.

Key words: Attitude of health personnel; Education, medical, undergraduate; Psychiatry; Students, medical

摘要

目的:用「精神醫學態度問卷」(ATP-30)探討尼日利亞醫學院即將畢業的醫科學生,在實習 前後對精神醫學的態度。

參與者與方法:實習前126位及實習後135位醫科學生參與本研究。

結果:實習前有54%學生取得問卷中位數(90分)以上的分數,實習後只有41%學生取得此分 數。實習後平均分數也明顯下降(p = 0.03):實習前90.6分(標準差:9.4),實習後88.2分(標準差:8.2)。分數明顯下降的有:教學課程方面、藥物治療後病人對其病況更為憂慮,及 作為精神科醫生所帶來的工作滿足感。

結論:醫科學生在實習後對精神醫學的態度有轉壞的趨勢。有需要在精神科教學課程上作出改 善。

關鍵詞:醫護人員的態度、醫科學生教育、精神科、醫科學生

Introduction

Mental disorders have been recognised for millennia, being initially considered to be physical ailments of the heart or uterus and therefore carried no stigma as there was no demarcation then between psyche and soma.1 Today, mental disorders carry a lot of stigmatising attitudes, which are often due to inaccurate information about mental illness or the lack of contact with individuals with mental illness. This was observed by Corrigan et al2 who indicated that those with more knowledge about mental illness were less likely to endorse negative or stigmatising attitudes.

Due to advances in neurosciences, neuroimaging and social sciences, nowadays the understanding of mental disorders is much improved. Notwithstanding better understanding and more effective interventions, attitudes towards mental disorders among the general public are still inappropriate.2 Medical students, being members of the larger general community, may also have such negative prejudices about mental disorders and psychiatric practice, despite having some contact with and knowledge of mental disorders. In 3 medical schools in North America, negative attitudes towards psychiatry were found to exist prior to formal medical training.3 Similarly, Furnham4 in London found that psychiatry was graded lowest among 8 other specialties and was given the most pejorative rating. It was considered the most ineffective, unscientific, and conceptually the weakest specialty.4 Interestingly, Reddy et al5 found that an 8-week clinical posting in psychiatry was associated with an increase in positive attitudes to mental illness and to psychiatry among female but not male students. Similarly, a study on Arabian Gulf University medical students also revealed moderately positive attitudes, which were also more evident in female than their male counterparts.6

Nigerian studies on the effect of the psychiatric clerkship on attitudes to psychiatry have indicated that over the period of posting to that specialty, attitudes were generally positive and remained fairly stable.7,8 These studies were undertaken 2 decades ago, hence there was a need for a re-appraisal. This study aimed at reporting the attitudes to psychiatry of final-year medical students of a Nigerian University medical college, prior to and after their clerkship.

Methods

A 2-stage cross-sectional study was carried out among final-year medical students in 2005 at the College of Health Sciences, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH), Osogbo, Southwest, Nigeria. This College serves Oyo and Osun, 2 of the 36 states in Nigeria, and the neighbouring Yoruba-speaking states, which forms the catchment area for the University. Students from other parts of Nigeria could also be admitted depending on merit.

The 6th-year psychiatric curriculum comprises 8 to 10 hours of didactic lectures per week. In addition, it includes 4 weeks of history taking, as well as sessions on mental status examination, communication skills, phenomenology, diagnostic classification, aetiology, clinical features, and the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Except when interviewing native Yoruba-speaking patients, all discussions and teaching materials were conducted in English. The psychiatry posting is in the final (6th) year, after exposure to other clinical specialties. These students formed the study population for this study. The department of psychiatry personnel included 4 board certified psychiatrists, physician psychiatrist trainees, psychiatric nurses, psychiatric social workers, and a clinical psychologist. Services rendered included: open inpatient acute– short stay assistance, substance abuse management, forensic psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatric services, geriatric psychiatric services, outpatient, community services and home visits, psychotherapy and counselling, and electro-convulsive therapy. Chronic, long-stay patients were not usually admitted but referred to a nearby Wesley Guild Hospital mental health department, under the care of one of the authors. Students were exposed to all the activities of these services units. The department enjoyed adequate liaison services with other medical, surgical, paediatrics, and obstetrics and gynaecology departments. There was also a working relationship with the local prison service and the local branch of the national drug law enforcement agency that covered appropriate forensic and drug exposure matters for the students.

We distributed questionnaires to all consenting students before the onset of posting (on their first day) and on the last day of the posting in psychiatry. Anonymity was maintained, because the respondents’ names or University matriculation numbers were not requested. We emphasised anonymity and confidentiality to overcome the possible tendency of the students to give answers perceived as acceptable to the investigators rather than representative of the respondents’ true opinions. It was explicitly stated that their responses would have no influence on their grades or examination performance. To avoid peer group influence, the students were not allowed to discuss their statements among themselves.

Measures

Demographic data measured included: age, gender, self- reported ethnicity and marital status. Attitudes to psychiatry were measured using the 30-item Attitudes to Psychiatry Scale (ATP-30).9 This Scale measures attitudes using a 5- point Likert scale (1 = agree strongly, 5 = disagree strongly) with questions about attitude to psychiatric patients, illness and treatment, psychiatrists, psychiatric institutions, teaching, knowledge, and career choice. The Scale had been used locally7 and internationally9 and had demonstrated good validity and reliability.9 It generates a global score between 30 and 150; a mid-score of 90, and higher scores indicate a relatively more favourable attitude to psychiatry.

For the purpose of this study we divided the ATP-30 into ‘domains’ and ‘facets’. Each question of the ATP-30 constituted a facet, while groups of facets formed a domain. Thus we had 4 domains: (1) attitude to psychiatry and mental illness; (2) attitude to psychiatric patients and psychiatric treatments; (3) attitude to psychiatrists and psychiatric institutions; and (4) attitude to psychiatric teaching and psychiatry as a career.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed to generate descriptive statistics, means and standard deviations using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version 11.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US).

Ethical Approval

The joint College of Health Sciences and LAUTECH Teaching Hospital Ethics Committee approved the study before commencement; a copy of the letter of approval can be obtained from the authors.

Results

A 100% response was achieved with a total of 126 students participating in the first part of the study. Four (3%) students did not indicate their gender, age, and marital status. Among the 126 students, 80 (63%) were males and 42 (33%) were females; 112 (89%) and 10 (8%) were single and married, respectively. The age distribution of the students indicated that 111 (88%) were in the range of 20 to 29 years, 10 (8%) were 30 to 39 years old, and 1 (1%) was older than 40 years. The majority of the students (n = 120) were of the Yoruba ethnic group.

A total of 135 students participated in the second phase of the study. These were made up of 87 (64%) males and 39 (29%) females, while 9 (7%) did not indicate their gender. A total of 116 (91%) were in the age range of 20 to 29 years, 10 (8%) were aged 30 to 39 years, and 1 (1%) was older than 40 years. Among the 135 students, 117 (87%) were single, 10 (7%) were married, and 8 (6%) did not indicate their marital status.

General Attitude to Psychiatry

Of the 126 students, 68 (54%) scored above the midpoint (90) pre-clerkship. Among the latter, 43 (63%) were males and 23 (34%) were females, while 2 (3%) indicated no gender.

Of the 135 post-clerkship students, 55 (41%) scored above 90 points, of which 33 (60%) were males and 18 (33%) were females, and 4 (7%) indicated no gender.

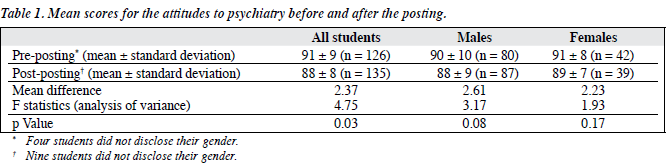

Table 1 shows that the proportion scoring above the neutral score (90) was higher at the beginning of the posting than the end, indicating that their general attitude declined over the posting, which was consistent with a significantly higher mean score at the beginning of the posting than at the end. The gender of the respondents did not seem to be the factor responsible for this change, as there was no statistically significant difference between gender-based mean scores before and after the posting.

This observed decline in attitude, however, was not universal with respect to all facets addressed by the questionnaire. For instance, in the domain ‘attitude to psychiatry and mental illness’ (Table 2), though not statistically significant, one of the factors actually showed a more positive attitude at the end of the posting. This was the belief that ‘the practice of psychiatry allows the development of really rewarding relationships with people’ about which a higher proportion of the students agreed after the posting, even though the percentage who agreed was already very high before the posting.

Three facets of the attitudinal questions showed a decline after the posting. These were ‘psychiatry is unappealing because it makes so little use of medical training’, ‘on the whole, people taking up psychiatric training are running away from participating in real medicine’, and ‘psychiatry is so amorphous that it cannot really be taught effectively’. The other facets in this domain showed a stable attitude before and after the posting, indicating that the training had little or no impact on the respondents’ beliefs.

Table 3 displays the attitudes to psychiatric patients and psychiatric treatments. There were more favourable responses on this domain after the posting than before. Only the facet, ‘psychiatric treatment causes patients to worry too much about their symptoms’ showed an appreciable and statistically significant increase in the proportions that agreed with this proposition after the posting. Other facets in this domain remained fairly stable after the posting. For example, approximately the same proportion believed there was little that psychiatrists could do for their patients, that the patients were often more interesting to work with than other patients, and that the practice of psychotherapy was not fraudulent.

On the domain that assesses the attitude to psychiatrists and psychiatric institutions (Table 3), only the facets ‘psychiatrists seem to talk about nothing but sex’ and ‘psychiatric hospitals have a specific contribution to make to the treatment of the mentally ill’ showed a rather marginal decline or incline in the responses. All other facets in this domain showed distinctly more positive attitudes at the end of the posting, though they were not statistically significant.

Table 3 shows that more students believed psychiatric teaching increased their understanding of medical and surgical patients and that the training in psychiatry had been valuable, and more wanted to become psychiatrists after the posting. This was against most respondents stating that they did not consider psychiatry to be among the 3 most exciting medical specialties.

Discussion

After the posting, there were 9 more students who responded to the same questionnaire than at the beginning. This was because some repeating students had to attend the end of posting examinations to boost their progressive assessment scores. According to College policy there was no way of excluding repeating students, since anonymity was maintained ab-initio and since technically they were all members of the class. Accordingly their answers were included and analysed with those of the original students.

This study found a generally poorer attitude to psychiatry at the end of the posting than before, as evident by significantly lower mean scores on the ATP-30. This was in contrast to earlier reports that attitudes to the specialty were positive over the period of the posting and remained fairly stable.7,8 It also contrasted with studies that reported a positive impact of undergraduate psychiatric attachments on medical student attitudes to psychiatry.5,10 This study, like another before it,10 did not find a significant gender difference in attitudes before or after the posting, which contrasted with reports that females had more favourable attitude to psychiatry.11,12 The performances of the students on each domain of the questionnaire provide probable reasons for the decline in attitude. On the domain ‘attitude to psychiatry and mental illness’, 3 of the 11 facets showed a downward trend while one showed an improvement and the remainder remained stable. The students’ responses could be interpreted as displeasure in terms of their expectations of psychiatry undergraduate training. The beliefs — that the subjects could not be taught effectively, that the discipline made little use of medical training, and that taking up psychiatric training was like running away from real medicine — all cast a shadow on the quality of the training they received. A possible explanation of this could be related to the way lectures were given. All the lectures with clinical activities could span from 8 am to as late as 6 pm. The duration of the posting was also short, lasting only 4 weeks. This could be stressful, as students often had to learn new terms to understand the psychopathology being described. This explanation appears supported by Dahlin and Runeson’s study13 that reported workload as one of the important factors responsible for stress and burnout among medical students. Similarly, there were few or no teaching aids to facilitate effective teaching and learning. This finding differed from that of a similar study in the United States,14 where students reported their psychiatric training as appealing. A change of lecture schedule and provision of learning incentives could help improve perceptions, by way of teaching aids such as slides, overheads, chalkboard and live patient presentations, so as to make didactic lectures more effective if properly used.15

The respondents showed a more positive attitude to psychiatric patients and psychiatric treatments (Table 3). These could be due to improvements in psychiatric treatments, especially the use of newer antipsychotic and anti-depressants drugs with reduced side-effect profiles. Better treatments had probably resulted in observable improvements in the symptoms of most patients. This observation therefore supports the World Health Organization summary in one of its technical reports.16 This stated that “Only when people are able to witness directly the efficacy of modern methods of treatment and the successful reintegration of the mentally ill person into society, will mental disorder lose its stigma. Health education campaigns to change public attitudes to mental illness are unlikely to be successful in the absence of adequate treatment services”. However, the observation that psychiatric treatment caused patients to worry too much about their symptoms could be due to the disturbing side-effects of these drugs, which can be more disabling than the primary symptoms of the illness.17 To improve on the attitude to psychiatric treatments, disabling drug side-effects should be effectively redressed. Certainly, the latter are reported to cause poor attitudes towards antipsychotic medication and the resulting quality of life of the patients.17

In this study, attitudes to psychiatrists and psychiatric institutions were generally positive. The respondents viewed psychiatrists to be as stable as other doctors and disagreed with the view that they were not equal to them. This positive attitude would go a long way towards reducing the stigma attached to people and facilities caring for patients with mental illness, and what Goffman18 referred to as “courtesy stigma”. This positive trend at the end of the posting, however, was contradicted by the downward trend in the views of the respondents, namely that psychiatrists get less satisfaction from their work than other specialists. This was possibly because psychiatrists in this hospital were not engaging in private practice outside the teaching hospital. Unlike other specialists, they were therefore unable to afford expensive cars and other luxuries. This low- pay status of psychiatry has been reported as a factor militating against recruitment to the specialty and also for the low rating of psychiatry as a career choice.19,20 Especially in this part of the world, where career success and satisfaction may be measured in material values, such factors could be very important.

In this study, the psychiatric ward was not viewed as akin to a prison. If the study had been conducted in a non- general hospital setting, such as a chronic long-stay psychiatric hospital, the views expressed might have been different.

On the possibility of pursuing psychiatry as a career, preferences were low, though there was an increase in the proportion of students who wanted to be psychiatrists after the posting. This low preference is similar to the findings reported in the UK,4,21 where psychiatry was the least popular clinical specialty. Reasons for such negative attitudes might include the perceived low respect for the discipline by other medical specialists and the low levels of remuneration.22 Although the psychiatry posting had a slight influence on the students’ willingness to specialise in psychiatry, the proportion not wanting to be psychiatrists also increased, as indicated by the increase in the proportions that disagreed with the statement ‘I would want to be a psychiatrist’. Similar findings were noted if students were asked to list the 3 most exciting medical specialties. The proportion of students that would exclude psychiatry increased marginally after the posting, which was at odds with other reports.5,10

Important findings in this study were that the majority of students reported psychiatric undergraduate training as valuable and that psychiatric teaching increased their understanding of medical and surgical patients. These observations were similar to earlier reports5,10 and like them showed improvement after psychiatric postings.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the general attitude to psychiatry by this group of medical students in this institution nose-dived after psychiatric exposure. Some of the areas that need to be improved include: the teaching of the subject, symptom worry being made worse by the treatment, and perceived job satisfaction of psychiatrists. The lessons to be drawn from this study are: psychiatry teachers should restructure the programme in a way as to make it more appealing, and consider the impact of having to assimilate new terms with which students are not familiar. An extension of the clerkship to between 6 and 8 weeks would allow students to learn the theory and practice of the subject better, as well as enable use of vignettes and trained simulators, as well as recorded tapes to demonstrate clinical skills. Teaching aids should also be available to the students in the form of audio- visual materials to assist learning. In this way the commonly held pessimistic attitudes towards the teaching of psychiatry could be challenged and help inspire more students to choose psychiatry as a career. Secondly the use of novel psychiatric drugs should be encouraged, because of their better side- effects profile and tolerability, and so as to reduce patient worry concerning drug side-effects. Thirdly, doctors who choose to specialise in psychiatry should be given more incentives, and perceived job satisfaction. By this means, psychiatrists as teachers and educationists might be able to influence more students to choose psychiatry as a possible career.

Limitations of the Study

One limitation of this study was that it was performed in a single institution, so that its findings may not be generalised to the entire country. Also it used internal controls (ie before versus after differences within the same group) rather than comparison with external controls. Similarly if the study had included students from other institutions, inter- institutional comparison might have been possible. The study participants were aware of our area of interests, which could have influenced some of the responses. The study was not longitudinal and therefore could not measure changes in attitudes and career choices later in life.

References

- Okasha A. Focus on psychiatry in Egypt. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:266-72.

- Corrigan PW, Green A, Lundin R, Kubiak MA, Penn DL. Familiarity with and social distance from people who have serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:953-8.

- Feifel D, Moutier CY, Swerdlow NR. Attitudes toward psychiatry as a prospective career among students entering medical school. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1397-402.

- Furnham AF. Medical students’ beliefs about nine different specialties. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:1607-10.

- Reddy JP, Tan SM, Azmi MT, Shaharom MH, Rosdinom R, Maniam T, et al. The effect of a clinical posting in psychiatry on the attitudes of medical students towards psychiatry and mental illness in a Malaysian medical school. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2005;34:505-10.

- Al-Ansari A, Alsadadi A. Attitude of Arabian Gulf University medical students towards psychiatry. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2002;15:180-8.

- Ekpo M, Ikkideh U. Attitude of medical students to psychiatry before and after a clerkship in psychiatry. Niger Med J 1989;19:185-8.

- Obembe JU. The attitudes of Nigerian fourth year students towards psychiatry. Niger Med J 1991;21:156-8.

- Burra P, Kalin R, Leichner P, Waldron JJ, Handforth JR, Jarrett FJ, et al. The ATP 30 — a scale for measuring medical students’ attitudes to psychiatry. Med Educ 1982;16:31-8.

- Samini M, Noroozi AR, Mottaghipour Y. The effects of psychiatric clerkship on fifth year medical students’ attitudes towards psychiatry and their intention to pursue psychiatry as a career. Iran J Psychiatry 2006;1:98-103.

- McParland M, Noble LM, Livingston G, McManus C. The effect of a psychiatric attachment on students’ attitudes to and intention to pursue psychiatry as a career. Med Educ 2003;37:447-54.

- Alexander DA, Eagles JM. Attitudes of men and women medical students to psychiatry. Med Educ 1986;20:449-55.

- Dahlin ME, Runeson B. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among medical students entering clinical training: a three year prospective questionnaire and interview-based study. BMC Med Educ 2007;7:6.

- Cutler JL, Alspector SL, Harding KJ, Wright LL, Graham MJ. Medical students’ perceptions of psychiatry as a career choice. Acad Psychiatry 2006;30:144-9.

- Gibbs G, Hobeshaw S, Habeshaw T. Improving student learning during lectures. Med Teach 1987;9:11-20.

- World Health Organization. Organization of Mental Health Services in Developing Countries: Sixteenth Report of the WHO Expert Committee on Mental Health. Geneva: WHO Technical Report. 1975. Report No. 564.

- Fleischhacker WW, Meise U, Günther V, Kurz M. Compliance with antipsychotic drug treatment: influence of side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1994;382:11-5.

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1963.

- Issa BA. Dearth of psychiatrists in Nigeria. Niger Med Pract 2005;47:127-8.

- Nielsen AC 3rd, Eaton JS Jr. Medical students’ attitudes about psychiatry. Implications for psychiatric recruitment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:1144-54.

- Rujagopal S, Rehill KS, Godfrey E. Psychiatry as a career choice compared with other specialties. Psychiatr Bull R Coll Psychiatr 2004;28:444-6.

- Balon R, Franchini GR, Freeman PS, Hassenfeld IN, Keshavan MS, Yoder E. Medical Students Attitudes and views of psychiatry 15 years later. Acad Psychiatry 1999;23:30-6.