Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2004;14(1):23-28

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

AJ Michael, S Krishnaswamy, F Badri-Alyeope, K Yusoff, TS Muthusamy, J Mohamed

Dr AJ Michael, BSc, Department of Biomedical Science, Faculty of Allied Health Science, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Professor

Dr S Krishnaswamy, MBBS, DPM, FRCPsych, AM, MSc, Professor and Senior Consultant, Department of Psychiatry, faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malayisa.

Dr F Badri-Alyeope, BSc, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malayisa.

Professor Dr K Yusoff, DPSK, MBBS, FAMM, FRCP (Edin), FRCP (Glasg), FRCP (Lond), FACC, Professor and Consultant, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malayisa.

Dr TS Muthusamy, MBBS, MRCP, CCST, Lecturer and Cardiology Physician, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malayisa.

Professor Dr J Mohamed, BSc, PhD, FABI, MACB, Professor and Deputy Dean (Academic and Student Affairs), School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Address for correspondence: Professor Dr Saroja Krishnaswamy, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Jalan Yaakob Latif, Bandar Tun Razak, 56000 Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Tel/Fax: (603) 9170 2665

E-mail: mailto:saroja@mail.hukm.ukm.my

Submitted: 28 December 2002; Accepted: 2 March 2004

Abstract

Objective: There is a significant correlation between stress and coronary artery disease when the stress is continuous and extreme. This study aims to determine the relationship between stress- related psychosocial factors, namely anxiety, depression, and life events, with ischaemic heart disease.

Patients and Methods: Two sets of questionnaires — The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Rahe’s Life Changes Stress Test — were administered to 3 groups comprising 36 patients with acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina, 38 outpatients from the Cardiology Clinic at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, and 25 healthy people from the community. All participants rated their feelings and reported any major lifestyle changes in the 6 months prior to interview.

Results: The study group had significantly higher odds of having had mild anxiety and depression and moderate-risk life events when compared to the healthy participants. There was no significant difference between the case group and the outpatients.

Conclusions: Psychosocial factors relating to stress is present in patients with acute ischaemic heart disease. Outpatients who have had long-term cardiac tribulation have the same odds for anxiety, depression, and life events as the patients with acute myocardial infarction.

Key words: Anxiety, Depression, Myocardial infarction, Psychological stress, Unstable angina

Introduction

The dramatic decline in cardiovascular disease in developed countries during the past 40 years is primarily due to the optimal intervention of traditional risk factors such as cigarette smoking, elevated total and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus.1 However, many of these patients continue to have cardiac events due to the emergence of other non-traditional predisposing factors such as psychosocial stress. Psychosocial stress worsens the risk associated with the traditional risk factors and contributes to mechanisms underlying cardiac events, especially endo- thelial dysfunction, myocardial ischaemia, plaque rupture, thrombosis, and malignant arrhythmias.2 Any programme designed to reduce morbidity and mortality of patients with coronary artery disease will be incomplete without addressing the relationship to stress.3

In Malaysia, the leading cause of death in government hospitals is cardiovascular disease, with coronary heart disease being the major cause of mortality (24.5% of all deaths in the government hospitals).4 Ischaemic heart disease such as acute myocardial infarction (MI) is a major health problem, with relatively high mortality and morbidity. Mental stress, in particular, has long been implicated as a potential trigger for MI and sudden cardiac death.5 Although risk of death or ischaemic complications with unstable angina is lower than with MI, patients with this condition were also included in the study as they tend to rapidly progress to MI and symptoms for most of these patients are caused by significant coronary artery disease.

Measuring psychological variables may address the mediators in which stress affects health or illness. Although the question of whether life events can increase the rate of psychiatric morbidity is still inconclusive, epidemiological studies attributed 32% of psychiatric illness to stressful life events.6 Developing either depression or anxiety has been linked to stressful life events involving loss (e.g., death of a loved one), which is more likely to lead to depression, while events involving threat (e.g., an accident) lead to anxiety.7 In this study, both anxiety and depression will be assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which establishes the presence and severity of both anxiety and depression simultaneously, while giving a separate score for each. Life events scores were measured using Rahe’s Life Changes Stress Test, a part of the Stress Coping Inventory.

Anxiety, through the activation of high-gain neuro- circuitry and the sympathetic nervous system, has been implicated in increased vulnerability to cardiac events.8 Phobic anxiety,9 especially among men,10 and generalised anxiety are predictors of MI and cardiac death.11 Depression is a psychiatric disorder caused by a combination of physical, emotional, biochemical, psychological, genetic, and social factors. Chronic stress and anxiety are known psychological risk factors for depression. Activation of the hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal axis is related to the stress response. However, recent findings show that similar activation of the axis plays a role in the onset of depression,12 especially in producing gender differences in the disorder.13 Although de- pression has not been linked with the initial onset of coronary disease, depressive symptoms contribute a significant independent risk factor for the onset of the disease, with a greater risk than passive smoking but lower than the risk caused by active smoking.14 However, the effects of the elevated levels of blood catecholamine that is caused by a dysregulated neurotransmitter system in depression could lead to endothelial injury, increased platelet aggregation, or electrical instability15 that tends to worsen the prognosis of patients with established coronary artery disease.16

This paper discusses the relationship between psycho- social factors, namely anxiety, depression, and life events, with ischaemic heart disease. Comparisons were made between patients with confirmed acute MI and unstable angina, cardiac clinic patients, and healthy controls.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The study group comprised patients admitted to hospital with acute MI or unstable angina referred by cardiologists from the cardiology wards of the Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Two groups of controls were included for comparison — the first were outpatients from the cardiac clinic who attended for follow up and the second were healthy volunteers from the community. The outpatients came from a pool of patients who had tested positive during stress echocardiography, and had undergone angioplasty or cardiac catheterisation. Some of these patients had a long history of cardiac tribulation, some dating back 11 years. The volunteers were people with no prior serious illness. All participants rated their feelings and recalled major events that had occurred during the past year of their lives using the HADS and the Life Changes Stress Test: Stress and Coping Inventory. The study group was interviewed with their consent 1 week after the cardiac events. Although the assessments were retrospective, reliability was improved by assuring confidentiality, administering simple objective questions, and confirming information with relatives. The confirmation with relatives is necessary to avoid distortion of recall among the patients. This effect is especially common among acutely ill cardiac patients who attempt to give meaning and explanation for their illness in terms of life experience.

Questionnaires

The HADS was used in this study for its ability to identify cases (possible and probable) of anxiety disorders and depression among patients in non-psychiatric hospital clinics.17 All symptoms of anxiety or depression relating to physical disorders such as dizziness, headaches, insomnia, and fatigue were excluded from the HADS. Symptoms relating to serious mental disorders that were less common in patients attending a non-psychiatric clinic were also excluded. The HADS was chosen due to its practicality and expediency.18 It is also self-rated; therefore, the rater’s bias is minimised. HADS scores for healthy individuals are below 8, while 8 to 10 indicates mild symptoms, 11 to 14 suggests moderate symptoms, and scores of 15 to 21 points suggest a severe state of depression/anxiety. The Life Changes Unit, which was taken from the Stress and Coping Inventory, has undergone reliability testing using Cronbach a correlations in a group of 1772 individuals.19 The scores for participants for ‘recent life changes’ were converted into the Life Changes Unit with several cut-off points to indicate susceptibility to illness. A total between 201 and 300 denotes a moderate risk and a total of 300 to 450 signifies an elevated risk for illness, although not specifically cardiac diseases. Total life events were divided into 4 domains of work, personal and social, financial, and home and family. Although health was also part of the Life Changes Stress Test, it was excluded in this study to avoid inclusion of factors due to cardiac events.

Statistical Analysis

The relationship between participants and anxiety or depression at 3 different categories of severity (8 to 10 = mild to moderate; 11 to 14 = moderate to severe; and >14 = severe) was determined using the Chi squared test. Total life events were grouped into 2 categories — the first was defined as scores above 201 (moderate to severe) and the second was defined as scores above 300 (severe). The odds ratio was estimated to establish the chances of patients in the study group developing these psychosocial factors compared with either or both of the control groups.

Characteristics

There were no significant differences in age for all 3 groups — study group (60 ± 12 years), control-outpatients (54 ± 16 years), and control-community (59 ± 11 years). The groups also displayed no significant differences in gender — study group (men, 52.8%; women, 47.8%), control- outpatients (50% for both men and women), and control- community (men, 36%; women, 64%) [Figure 1]. Regarding the ethnicity, the participants consisted of the 3 dominant races of Malaysia with a group total of 41% Malay, 26% Chinese, and 32% Indian. Although the Malays remained the dominant race for the study and community groups when considered separately, 50% of the outpatients were Indians (Figure 2). For the study group and the community group, there were more Chinese participants than Indians. The distribution according to ethnicity showed a significant association between the races and groups (Chi squared = 10.425, p < 0.05).

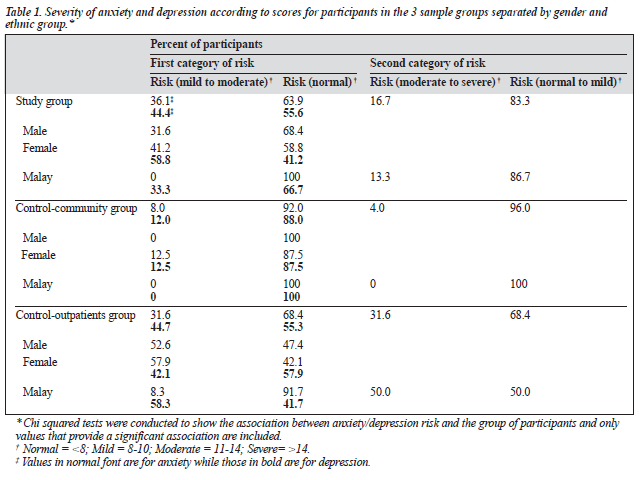

Anxiety

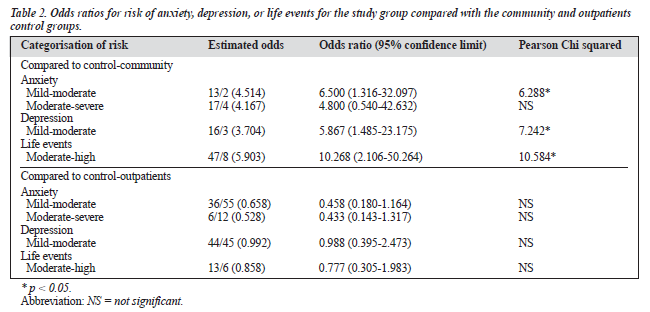

The study categorised anxiety risk into 3 sets depending on the scores. Sixty six percent of the participants had normal scores for anxiety (below 8), with the study group having 65% in this category, while the control-outpatients had less than half of its participants (45%) and the control-community had almost all the participants (92%) in this category. There was a similar distribution of participants for both mild and moderate risk for all 3 groups with the outpatients having 24% and 26% of its patients for these categories, respec- tively. No severe cases were reported for the community group while the other 2 groups each had a patient with anxiety scores >14. A significant association was found between the groups of patients and anxiety risk for mild to moderate risk (Chi squared = 14.558, p < 0.001) and moderate to severe risk (Chi squared = 7.628, p < 0.05) [Table 1]. When separated by gender, both men (Chi squared = 7.629, p < 0.05) and women (Chi squared = 7.641, p < 0.05) displayed a significant relationship between the 3 groups and anxiety risk for mild to moderate anxiety and there were more women in the study group (41%) at risk than men (32%). For ethnic group, only the Malays showed a significant association between the groups and anxiety at the mild to moderate risk (Chi squared = 7.264, p < 0.05) and moderate to severe risk (Chi squared = 8.251, p < 0.05). Study patients were 7-fold more likely (odds ratio, 6.500) than community participants to be at risk for mild to moderate anxiety. However, the odds of study patients and outpatients for this risk was the same and there was no significant difference between them (Table 2).

Depression

For depression scores, a similar categorisation to anxiety was performed with scores at 8 to 10 (mild to moderate), scores at 11 to 14 (moderate to severe) and scores above 14 (severe). Having a normal score of less than 8 was the commonest category for all 3 groups — study group (53%), control-community group (55%), and control-outpatients (58%). No severe cases were reported for the study and community groups, while there was 1 outpatient with depression scores >14. Only the community group had a significant difference in depression scores when compared to the study group (p < 0.001). Unlike anxiety, depression risk was significantly associated with group only when risk was defined at scores >8 (Chi squared = 8.580, p < 0.05) [Table 1]. When a more detailed grouping based on demographics was done, only women (Chi squared = 7.641, p < 0.05) and the Malays (Chi squared = 10.810, p < 0.05) showed a significant association. No association was found when the risk scores were increased to either >10 or >14. Participants in the study group had significantly higher odds of having depression (odds ratio, 5.867; Chi squared = 7.242) compared with the community group (Table 2).

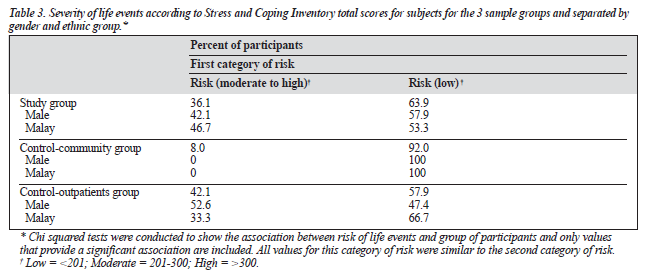

Life Events

Total life events were grouped into 2 categories of risk — the first was risk defined as scores >201 (moderate to severe) and the second as scores >300 (severe). Life events for low risk of scores <201 had the highest percentage (69%) for all 3 groups with the study group having 61%, 58% for the community group, and 55% for the outpatients in this category. There were 5 and 7 severe cases for the study and outpatient groups, respectively, with none for the commu- nity group. Only the community group had a significant difference in life events scores when compared with the study group (p < 0.001). Life events was equally significantly associated with group at both categories of risk (Chi squared = 8.761, p < 0.05) [Table 3]. A further analysis found that men (Chi squared = 7.355, p < 0.05), but not women, were significantly associated with grouping of subjects. Malays were the only ethnic group with a very significant association (Chi squared = 13.414, p < 0.001). Total life events were a sum of points from 4 areas in life — work, personal and social, financial, and home and family. When the study group was compared with the community group, the areas of personal and social (t = 4.14; p < 0.001); and home and family (t = 3.48; p < 0.001) were significantly different. Events encompassing financial and work were similar for all 3 groups. There was a 10-fold likelihood of a person in the study group having life events in the past year compared with the community group (Table 2). In the experience of life events, as for both anxiety and depression, there was no significant difference between study patients or outpatients groups.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to determine the association between stress-related psychosocial factors and the onset of either acute MI or unstable angina. Anxiety and depression were significantly different among the 3 groups when risk was set at >8.

For anxiety, there was a significant association when the scores for risk were increased to moderate to severe risk. However, when the odds ratio was tabulated, study patients were more likely than community participants, but not outpatients, to have low, but not moderate, anxiety. The similarity between study patients and outpatients was because anxiety was not only found to be prevalent at baseline in patients admitted to hospital for MI,20 but was also one of the psychosocial variables that predicted cardiac events occurring the first year after MI.21 More women than men had risk for anxiety in the study group. Women in the variety of cultures were found to have higher anxiety than men after acute MI, and this relationship was independent of age, education level, marital status, or presence of comorbidities or severity of the MI.22

For depression, only women displayed differences among the groups. Those with acute MI or unstable angina had higher chances of having mild depression compared with those without any type of cardiac disease. The equal chance of the study group and outpatients of having depression signifies that it is present in all types of cardiac tribulation. In our findings, 1 outpatient had severe risk for depression, in agreement with studies that found that major and clinical depression were significant predictors of cardiac events during the first year after MI.23 This could be caused by the patient’s sense of hopelessness and incapability of making behaviour changes to reduce cardiac mortality. When patients with a long history of cardiac events were inter- viewed they revealed that they were more tense, terrified, and depressed due to the poor state of their health. They also were more anxious and worried as they were aware of the seriousness of their illness.

For moderate to severe life events, unlike for depression, men exhibited differences among groups when separated by gender. Many different types of stressors independently contribute to poor health outcome.24 Stressful life events can trigger acute MI and sudden cardiac death.25 Major life changes and transitions are often viewed as stressors and require adjustments to one’s lifestyle.26

Clinical Implications

Psychosocial factors such as anxiety, depression, and life events have been linked to increased morbidity and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease.27 These findings have clinical applications for diagnosis, treatment, and the evaluation of medical care for cardiac patients. The impact of psychosocial stress on the development of acute ischaemic heart disease was similar to other cardiac complications. These patients showed significant differences from those without cardiac events for mild risk of anxiety, depression, and life events and this was similar to patients with congestive heart failure who experience moderate levels of depression, but not greatly heightened anxiety.28 Congestive heart failure is the end stage of heart failure and MI is one of the antecedents for the onset of this disease. Psychosocial treatment, which includes education, counselling, and psychosocial interventions, provides additional benefit over standard care.29 Cardiac rehabilitation practised in Malaysia focuses on improving the psychical, psychological, and social well-being of patients following an acute MI, which involves an inpatient and outpatient phase.30 However, reduction of anxiety and psychological disturbances are involved only at the inpatient phase. During the outpatient phase, follow-up includes promotion of healthy lifestyles but modification of risk factors, stress, and stress-related psychosocial factors are not specifically emphasised. Highly stressed patients with acute MI who underwent stress monitoring and intervention did not experience any significant long-term increased risk of cardiac mortality and MI recurrence.31 Stress management programmes, in particular those that focus on relaxation therapy, have significantly decreased cardiac events among patients after acute MI.32 Health practitioners and researchers should question patients about their recent history of stress events in addition to the examination of the biological aspects of the illness as both aspects may have notable effects on health status.

Acknowledgements

The research in this article was made possible by the IRPA 06-02-02-0121 project grant. We also thank the Ethical Committee, Faculty of Medicine, and the participants involved in the study.

References

- Stamler J. Epidemiology, established major risk factors, and the primary prevention of coronary artery disease. In: Chatterjee K, Cheitlin MP, Karlines J, editors. Cardiology: an illustrated text/reference. Vol 2 Part

- Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1991.

- Merz C, Bairey N, Dwyer J, et al. Psychosocial stress and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiological links. Behav Med 2002;27:141-147.

- Slay CL. Myocardial infarction and stress. Nurs Clin North Am 1976; 11:329-338.

- AMI death in the Government Hospital Malaysia 1990-1998. Unit Sistem Maklumat dan Dokumentasi, Bahagian Perancangan dan Pembangunan, Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Minstry of Health Malaysia.

- Krantz DS, Kop WJ, Howell RH, et al. Effects of mental stress on coronary epicardial vasomotion and flow velocity in coronary artery disease: relationship with hemodynamic stress responses. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:1359-1366.

- 6. Cooke DJ, Hole DJ. The aetiological importance of stressful life ev Br J Psychiatry 1983;143:397-400.

- Finley-Jones R, Brown GW. Types of stressful life event and the onset of anxiety and depression disorders. Psychological Med 1981;168:50-57.

- Verrier RL, Mittelman MA. Cardiovascular consequences of anger and other stress states. Baillieres Clin Neurol 1997;6:245-259.

- Haines AP, Imeson JD, Meade TW. Phobic anxiety and ischaemic heart disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;285(6593):297-299.

- Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, et al. Prospective study of phobic anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Circulation 1994;89:1992-1997.

- 11. Paterniti S, Zureik M, Ducimetiere P, Touboul PJ, Feve JM, Alperovitch Sustained anxiety and 4-year progression of carotid atherosclerosis Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001;21:136-141.

- Checkley S. The neuroendocrinology of depression. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996;8:373-378.

- 13. Halbreich U, Lumley LA. The multiple interaction biological processes that might lead to depression and gender differences in its J Affect Disord 1993;29:159-173.

- Pratt LA, Ford DE, Crum RM. Depression, psychotropic medication and risk of myocardial infarction: prospective data from the Baltimore ECA follow-up. Circulation 1996;94:3123-3129.

- Siever LJ, Davis KL. Overview: toward a dysregulation hypothesis of depression. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:1017-1031.

- Barefoot JC, Schroll M. Symptoms of depression, acute myocardial infarction, and total mortality in a community sample. Circulation 1996;93:1976-1980.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.An updated review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69-77.

- Roberts SB, Bonnici DM, Machinnon AJ, Worcester MC. Psychometric evaluation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) among female cardiac patients. Br J Health Psych 2001;6:373-383.

- Rahe RH, Veach TL, Tolles RL, Murakami K. The Stress and Coping Inventory: an educational and research instrument. Stress Med 2000; 16:199-208.

- Crowne JM, Runions J, Ebbesen LS, Oldridge NB, Streiner DL. Anxiety and depression after acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung 1996; 25:98-107.

- Frasure-Smith N, Prince R. The ischemic heart disease life stress monitoring program: impact on mortality. Psychosom Med 1995; 47(5):31-45.

- Moser DK, Dracup K, Mckinley S, et al. An international perspective on gender differences in anxiety early after acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med 2003;65:511-516.

- Conn V, Taylor S, Wiman P. Anxiety, depression, quality of life and self-care among survivors of myocardial infarction. Issues Ment Health 1999;12:321-331.

- Leserman J, Li Z, Hu YJ, Drossman DA. How multiple types of stressors impact on health. Psychosom Med 1998;39:158-177.

- Stalnikowicz R, Tsafrir A. Acute psychosocial stress and cardioavascular events. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:488-491.

- Euehun L, Moschis GP, Mathur A. A study of life events and changes in patronage preferences. J Business Res 2001;54:25-28.

- Buselli EF, Stuart EM. Influence of psychosocial factors and biopsychosocial interventions on outcomes after myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Nurs 1999;13:60-72.

- MacMahon KMA, Lip GYH. Psychological factors in heart failure: A review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:509-516.

- Cossette S, Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F. Clinical implications of a reduction in psychological distress on cardiac prognosis in patients participating in a psychosocial intervention program. Psychosom Med 2001;63:257-266.

- Fonaraw GC. UCLA Clinical Practice Guidelines on Acute Myocardial Infarction. Los Angeles: University of California (Clinical Guideline Committee, UCLA Division of Cardiology); 2001.

- Smith F. In-hospital symptoms of psychological stress as predictors of long-term outcome after acute myocardial infarction in men. Am J Cardiol 1991;67:121-127.

- Van Dixhoorn JJ, Duivenvoorden HJ. Effect of relaxation therapy on cardiac events after myocardial infarction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 1999;19:178-185.