Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2006;16:3-6

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

R Mahendran, M Hendriks, V Thambyrajah, T Vellayan, MS Maarof

Clin Assoc Prof Rathi Mahendran, M Med (Psychiatry), FAMS, Department of Psychiatry, Institute of Mental Health, Woodbridge Hospital, Singapore.

Ms Margaret Hendriks, BHS (Nursing), Adv Dip Adm Mgt, Case Management Unit, Institute of Mental Health, Woodbridge Hospital, Singapore.

Mr Vamadevan Thambyrajah, BHS (Nursing), Adv Dip Case Mgt, Case Management Unit, Institute of Mental Health, Woodbridge Hospital, Singapore.

Ms Thamilselvi Vellayan, RN (Psychiatry), Adv Dip Case Mgt, Case Management Unit, Institute of Mental Health, Woodbridge Hospital, Singapore.

Mr Mohammed Saifudin Maarof, RN (Psychiatry), Adv Dip Case Mgt, Case Management Unit, Institute of Mental Health, Woodbridge Hospital, Singapore.

Address for correspondence: Clin Assoc Prof Rathi Mahendran, Institute of Mental Health, Woodbridge Hospital, 10 Buangkok View, Singapore 539747.

Tel: (65) 6389 2000; Fax: (65) 6385 5900; E-mail: Rathi_MAHENDRAN@imh.com.sg

Submitted: 5 December 2005; Accepted: 22 May 2006

Abstract

Objective: Case management is a heterogeneous concept used in psychiatry and other health, welfare, and service sectors. The several models of case management in psychiatry can be viewed as arising from task areas of psychiatric care, namely medical, rehabilitation, social control, growth, and development. This study investigated the development of the brokerage model of case management in acute psychiatric care in a psychiatric hospital.

Patients and Methods: 227 patients referred to the psychiatric case managers between November 2003 and October 2004 were included in this health service review. The psychiatric case managers maintained their own databases as well as recording information in the patients' medical records. The information from these databases was collated for review.

Results: There was a significant decrease in the number of hospital readmissions, following the introduction of case management from 65 to 26 (p = 0.001). There was a decrease in the number of patients who defaulted follow-up appointments from 24.0% for all outpatients to 11.9% for patients receiving case management (p = 0.001). The average number of days per admission was reduced from 15.6 days to 4 days (p = 0.001).

Conclusion: The cost-effectiveness of the case management service is reflected by the reduc- tion in hospital readmission and duration of hospital stay.

Key words: Case management, Patient admission, Psychiatry

Introduction

Case management has been extensively studied in western countries. There has been debate about the effectiveness of psychiatric case management but recent meta-analyses have indicated effectiveness in various areas1,2 These areas include reduction in symptoms, reduced dropout rates, increased patient contact with services, improved social functioning, and reports of service satisfaction. There has been limited research on psychiatric case management in Asia and there are only a few reports of its efficacy and cost-effectiveness in Asian settings.3 The Commission for Case Management Certification defines case management as a collaborative process that assesses, plans, implements, coordinates, monitors, and evaluates the options and ser- vices required to meet an individual's health needs using communication and available resources to promote quality and cost-effective outcomes.4

The Institute of Mental Health, Woodbridge Hospital, Singapore, is a 2210-bed psychiatric hospital. The average bed occupancy is 1910 (from the average daily inpatient census taken from 1 August 2004 to 31 August 2004) and, together with general hospital psychiatric units, serves a population of 4.24 million.5

Case management was introduced in the hospital in 2000, first as part of an Early Psychosis Intervention Program and later for the general adult psychiatry service. The hospital's objective was to provide quality care that is comprehensive and effective for patients and to reduce the burden of chronic and severe mental illness on patients' families and society. Psychiatric patients in Singapore, similar to those in other countries, experience a wide range of debilitating psychi- atric problems, inadequate social support, and multiple stressors. Community resources tend to be fragmented and are limited in some areas, for example, housing. A second- ary objective was to use case management to expand and enhance community psychiatric services in Singapore.

Case management has been conceptualised in different ways.6 Mueser et al described 6 models of case manage- ment as: brokerage, clinical, strength, rehabilitation, assert- ive community, and intensive.7 For the service needs of the hospital, a brokerage model of case management was adopted. The brokerage model has sometimes been criticised for providing minimal direct service to patients. Despite this, the model was selected for its applicability to the hospital setting and it enabled services to be arranged from amongst those available in the community.8

Thornicroft's basic premise of case management as the coordination, integration, and allocation of individualised care within limited resources was used in planning the de- livery of care.9 The following functions delineated by Stein and Diamond were included: psychosocial needs assessment, individualised care plans, referral and linkage to appropri- ate community services and resources, monitoring of men- tal state and response to treatment, treatment compliance and side effects, establishing and maintaining a therapeutic relationship, counselling and supportive therapy, and psycho-education.10

Four psychiatric nurses were recruited as psychiatric case managers and underwent a 1-month training course in case management, practical supervision, and a part-time train- ing course (the Advanced Diploma in Case Management) at a local polytechnic. The nurses were assigned to the 3 general psychiatry departments, with one department in- volved in forensic psychiatry receiving an extra case manager. Case managers were accountable to their respect- ive department heads for all clinical matters and to the head of the Case Management Unit for administration and training.

The case managers' roles and responsibilities were clearly defined. Each case manager had to take responsibil- ity for a particular patient, involving the following:

- case management role: development of care plan, coordination, and continuity of care from hospital to community

- brokerage role: assessor, planner, evaluator

- therapeutic role: providing psycho-education for patients and their families, as well as counselling and supportive therapy.

In their daily activities, the case managers were expected to review admissions in their assigned wards, to identify patients' problems and determine their need for case man- agement services, and to manage patients referred by the inpatient ward staff (Figure 1).

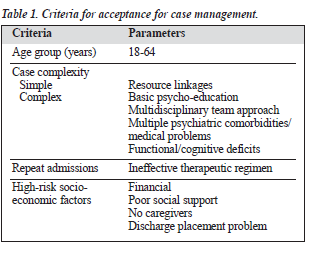

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for referral to the service were prepared, to assist hospital staff to make appropriate referrals to the case managers. These included: age 18 to 64 years (as the case managers provided services only in the adult general psychiatry wards) and those patients with a history of repeated admissions, functional and/ or cognitive deficits, or high-risk social factors (Table 1). The case managers also categorised the level of care and services provided. This ranged from level I case manage- ment, which involves assessment and counselling with minimal follow-up, to level IV case management, which entails intensive work with patients and their families, and telephonic case management.

Outcome measures were introduced at the outset to help review the service. These included: maintaining the unplanned readmission rate below the hospital rate of 10%, reducing the number of admissions requiring police assistance, monitoring the duration of hospital stay, reducing follow-up default, and reducing forensic complications.

This paper presents the outcomes of case management in the acute inpatient wards of a psychiatric hospital after 1 year and briefly outlines the changes made in the case management service following the review.

Patients and Methods

All patients referred to the psychiatric case managers be- tween November 2003 and October 2004 were included in this health service review. The psychiatric case managers main- tained their own databases as well as recording information in each patients'hospital medical records. The case managers were part of the multidisciplinary treatment team and coordinated the care and integrated the services of each patient in the acute psychiatric setting. The information from the case managers' databases were collated for the purpose of this review.

Results

Patients

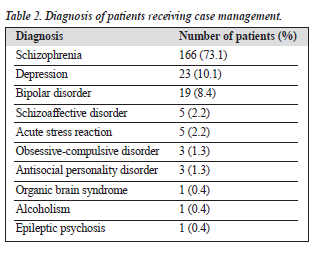

1191 patients were referred to the psychiatric case managers during the 12-month period. 227 patients (19.1%) were accepted for case management. The male-to-female ratio was 1.2:1. There was a predominance of Chinese patients (77.1%) followed by Malay (11.4%), Indian (10.6%), and other (0.9%); the racial distribution of the study patients closely follows that of the state. Regarding marital status, 72.7% of patients were single, 21.1% were married, 2.6% were widowed, and 3.6% were divorced. The predominant diagnosis was schizophrenia (73.1%), followed by de- pression (10.1%), bipolar disorder (8.4%), schizoaffective disorder (2.2%), and acute stress reaction (2.2%) [Table 2].

Service Provision

896 sessions of psycho-education were provided, compris- ing group and individual sessions. Standardised teaching materials were used. 377 individual counselling sessions were provided, averaging 1.6 sessions per patient. There were 103 family counselling sessions, with an average of 1 session for every 2 families.

The psychiatric case managers referred patients to other services provided by the hospital. Thirty two patients (14.1%) were referred to the Assertive Community Treat- ment (ACT) team and 35 patients (15.4%) were referred to the Community Psychiatric Nurses (CPNs). Referral to the ACT team and the CPNs is guided by the criteria set by these teams. As the ACT team is community based and provides psychosocial rehabilitation, the psychiatric case managers referred patients who would benefit from close supervision, support, and rehabilitation in the community. The other criteria for referral to the ACT team included significant disability from serious mental illness and more than 3 hospital admissions per year.

Ninety nine patients (43.6%) were referred to psycho- logists, medical social workers, and/or occupational thera- pists for assessment, counselling, and other interventions. Many referrals to the medical social workers were for finan- cial assistance. The psychiatric case managers provided crisis management for 14 patients (6.2%). Case managers also undertook telephonic case management for outpatients and made 1436 telephone calls, averaging 6.3 telephone calls per patient during the year. Twenty seven home visits were made and 37 patients (16.3%) were discharged during the year.

Hospital Admission

Unplanned hospital readmission within 28 days of discharge is a key performance indicator. The target incidence is less than 9%. Only 11 patients (4.8%) in the care of case managers were readmitted within 28 days of discharge; 15 patients (6.6%) were readmitted after 28 days. Only 4 patients (1.7%) receiving case management required police assistance for readmission compared with 16.4% of emergency room attendances.

There was a significant decrease in the number of hos- pital readmissions in the year following the introduction of case management, from 65 to 26 (p = 0.001). There was also a significant decrease in the number of patients who de- faulted follow-up appointments (11.9% for patients receiving case management compared with 24% for all outpatients; (p = 0.001). The case managers telephoned patients to remind them of their clinic appointments. The total duration of hospital stay decreased from 1014 days in the year before case management was instituted to 104 days the following year (p = 0.001); the average number of days per admission decreased from 15.6 days to 4.0 days (p = 0.001). In the comparison of duration of hospital stay, the index admis- sion when referrals to the case manager were made was excluded.

Other Outcomes

Sixteen patients attempted suicide. One patient with mul- tiple significant psychosocial problems successfully com- mitted suicide 3 weeks after discharge from hospital. Of the other patients, 4 had forensic complications, 2 committed theft, 1 assaulted a staff member at another hospital, and 1 was involved in a fight.

Discussion

These findings were derived from a health service audit and provide important baseline data for the introduction of a case management service in an acute psychiatric hospital. Based on these data, systems and processes can be improved upon. However, as this was a health service audit, there are limitations in the data available for analysis and there was no control group established for comparison. The focus was to assess the workload and patient outcomes.

Only 20% of patients referred to the case managers were accepted for case management. It is likely that at the start of a new service, patients were referred without consideration of the referral criteria. The criteria are important as they ensure that case managers are available to provide care for those who need it and are most likely to benefit. The pa- tients not accepted for case management were not denied help and were assisted by members of the multidisciplinary treatment team. However, a comparison with this group is unavailable.

It is evident that the case management service served to increase the number of patients who remained in contact with the psychiatric service compared with the outpatients department. Although the rate of unplanned readmissions within 28 days is already below the hospital's key perform- ance indicator of 9%, efforts to improve this rate will continue. Although the cost-effectiveness of the service was not definitively calculated, the effectiveness of the service was clearly demonstrated by the reduction in the number of readmissions and duration of hospital stay.

More rigorous data collection and good-quality outcome measures are necessary. Objective documentation of the symptomatology of the patients, including the use of appro- priate rating scales, which are considered useful measures of service outcomes would enhance the review findings. However, the overall results indicate that case management is successful in reducing the number and duration of hospi- tal admissions. The use of hospital re-admissions provides only indirect evidence of stabilisation of a patient's symptom- atology and the use of hospital admission as an outcome measure has been criticised.11 Quality of life and improve- ment in mental health will be monitored in the coming year. In addition, findings from patient- and family-satisfaction assessments will indicate the perceived value of the service.

The case management team has reviewed the service delivery system and this has been re-categorised to more accurately reflect the intensity and level of care and ser- vices provided. Similar to case management services in the UK, no one model has been strictly adhered to. Instead, the critical and most effective aspects of case management have been used. Difficulties were encountered with brokerage services, especially in the first year, as other members of the multidisciplinary treatment team had to adjust to the roles of case managers. This was resolved by face-to-face dis- cussions and delineating the roles of each member of the multidisciplinary team.

The case managers also felt the need to enhance their knowledge and have initiated monthly peer review sessions for case discussions and journal clubs. They attend bi- monthly meetings with case managers in other settings to exchange ideas and for training purposes. This is an impor- tant step as there is a paucity of research about good case management and the skills required for this role.12 There has been criticism that negative outcomes from case man- agement studies may have arisen because of a general lack of training and relevant interventions.13

This review has not addressed the issue of costs but focused entirely on service delivery. The case management service provided in the psychiatric hospital covered a contin- uum of care from inpatient acute wards to outpatient follow- up. Its broad and generalist goal is to identify the special needs of patients with severe mental illness, assist in their recovery and help them to maintain a stable life in the community. As highlighted by Sledge et al, as case manage- ment advances, there will be a need to identify which types of case management are useful for which patient population.14

References

- Ziguras SJ, Stuart GW, Jackson AC. Assessing the evidence on case management. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:17-21.

- Rosen A, Teeson M. Does case management work? The evidence and the abuse of evidence-based medicine. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2001;35: 731-46.

- Chan S, Mackenzie A, Jacobs P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of case management versus a routine community care organization for patients with chronic schizophrenia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2000;14:98-104.

- Commission for Case Management Certification, CCM Certification Guide. Rolling Meadows: Commission for Case Management; 2003.

- Health Facts Singapore 2005. Singapore: Health Information Manage- ment Branch, Ministry of Health; 2005.

- Solomon P. The efficacy of case management services for severely mentally disabled clients. Community Ment Health J. 1992;28: 163-80.

- Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE. Models of community care for se- vere mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:37-74.

- Bedell JR, Cohen NL, Sullivan A. Case management: the current best practices and the next generation of innovation. Community Ment Health J. 2000;36:179-94.

- Thornicroft G. The concept of case management for long-term mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1991;3:125-32.

- Stein L, Diamond J. A program for difficult-to-treat patients. New Dir Ment Serv. 1985;26:29-31.

- Bachrach L. Assessments of outcomes in community support systems: results, problems and limitations. Schizophr Bull. 1992;8:833-34.

- Sherlock-Storey M, Milne D. What makes a good care manager? An analysis of care management skills in the mental health services. Health Soc Care Community. 1995;3:53-64.

- Muijen M, Cooney M, Strathdee G, Bell R, Hudson A. Community psychiatric nurse teams: intensive support versus generic care. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;165:211-17.

- Sledge WH, Astrachan B, Thompson K, Rakfeldt J, Leaf P. Case man- agement in psychiatry: an analysis of tasks. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152:1259-65.