Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2007;17:10-2

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr S George, MRCPsych, Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Trust, Birmingham, England B37 7UR.

Dr Karen Moreira, MBBS, Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Trust, Birmingham, England B37 7UR.

Address for correspondence: Dr S George, MRCPsych, Consultant in Addiction Psychiatry, Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Trust, Birmingham, England B37 7UR.

Tel: 0121 6784900;

E-mail:sanju.george@talk21.com

Submitted: 29 January 2007; Accepted: 13 March 2007

Abstract

Objectives: Cultural sensitivity is key to understanding and treating patients in today's multi-cultural societies. In this study, we compared the characteristics of 2 hospital coffee shops in India and England and their attendees' opinions. We also discuss the results and their implications from a cross-cultural perspective.

Participants and Methods: Convenience samples of 50 attendees each from 2 hospital coffee shops in India and England were interviewed. A short, pre-designed questionnaire was used to collect information and rate their opinions.

Results: There were considerable differences between the English and Indian hospital coffee shops in their functioning and in the views of their attendees. Despite the objective evidence, attendees at the Indian coffee shop rated it higher on cleanliness and all other parameters than did those using the English coffee shop. It is also worth noting that attendees at both the hospital coffee shops preferred their own coffee shop when shown photographs of the other coffee shop.

Conclusions: What seems appropriate in one culture might not be so in another and it would be ethnocentric to assume otherwise. Cultural sensitivity is key to developing psychiatric services that adequately meet the needs of a culturally diverse population. Although this study only included hospital coffee shops in England and India, it is reasonable to argue that the findings may be generalisable in different cultural settings.

Key words: Acculturation; Cross-cultural comparison; Hospital shops

摘要

目的:在現今多元文化的社會,文化敏感度是了解及治療患者的關鍵。本研究比較印度和英國兩間醫院咖啡店的特性及顧客的意見,並以跨文化角度探討研究結果和其含意。

參與者與方法:以便利抽樣形式,分別訪問50名來自印度和英國醫院咖啡店的顧客,並以預先設計的簡短問卷蒐集資料及他們的意見以作評估。

結果:結果顯示,兩地醫院咖啡店在功能及顧客意見上有顯著的差異。儘管有客觀的憑證, 印度醫院咖啡店的顧客在清潔衛生及其他參數的評價都遠較英國的為高。值得一提的是,即使向受訪者出示另一國家醫院咖啡店的相片,他們仍願意選擇己國的醫院咖啡店。

結論:研究推測這種看似適合某一文化,而可能不適用於另一文化的情況。文化敏感度是發展迎合多元人口需要的精神病學服務的關鍵。雖然此項調查只包指英國和印度的醫院咖啡店,但仍可考慮將研究結果應用於其他文化背景上作分析研究。

關鍵詞:同化過程、跨文化比較、醫院商店

Introduction

“To try to understand the experience of another it is necessary to dismantle the world as seen from one’s own place within it, and to reassemble it as seen from his.”1

Mr A was early for his outpatient appointment and hence 1 of the authors (SG) suggested that he goes to the hospital coffee shop for a drink. He came back 5 minutes later and said “It’s not the same...I prefer the less glamorous and more traditional coffee shops outside hospitals in India.

It’s so much more personal...” That prompted the questions: Are hospital coffee shops in England and India any different? Did this patient’s comment mean that the cross- cultural underpinnings of hospital coffee shops need further exploration? Or had this man who had migrated to England in the 1970s still not acculturated to life in England?

Hospitals across the world have ‘in-house’ or attached coffee shops, yet their role and usefulness have not been previously studied. We set out to study the characteristics and attendees’ opinions of 2 hospital coffee shops: 1 in England (West Midlands) and the other in India (Kerala). The results are briefly discussed within the context of the cross-cultural lessons that clinicians and psychiatrists could learn and incorporate into their practice in today’s multicultural societies.

Methods

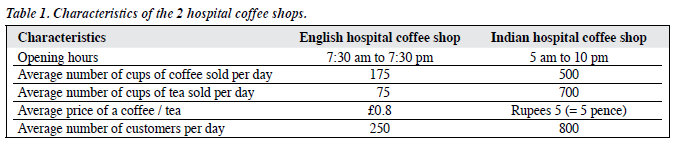

Two hospital coffee shops were studied: 1 in England (West Midlands) and the other in India (Kerala). Table 1 highlights some of the features of these 2 coffee shops. The hospital coffee shop in England caters to a 200-bed NHS hospital and is located inside the hospital building. The coffee shop in India is one of many, located just outside the hospital building (as most hospital coffee shops there are) and this hospital is a 1000-bed, privately-run hospital.

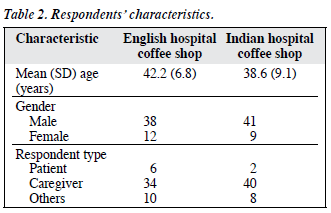

The authors interviewed 50 attendees at both coffee shops (convenience sampling done over 2 days), a month apart. Each interview lasted approximately 15 minutes. After being asked their age with their gender recorded, they were then asked to rate the local coffee shop (on a scale of 1 to 10) on the following 4 parameters: cleanliness, customer friendliness, quality of drinks / food, and overall satisfaction. They were also asked 2 open-ended questions: ‘Why do you come here?’ and ‘Would you like anything to change?’ Each respondent was then shown a picture of the hospital coffee shop in the other country and was asked ‘Which coffee shop would you prefer?’ Responses to all questions were recorded during the interview and were later analysed.

Results

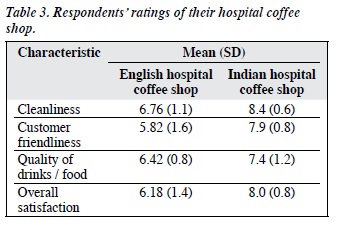

Descriptions of the attendees and their ratings of the local hospital coffee shops are given in Tables 2 and 3. Attendees at the Indian coffee shop gave a range of reasons for going there: have a drink (90%), to meet and talk to people (56%), and to relieve tension (20%). Those in England gave the following reasons: to have a drink (90%), to talk (42%), and to relax (24%). Despite the objective lack of cleanliness, none of those in India wanted any aspect of the coffee shop to change while those in England commented on the lack of cleanliness (28%), delay in service (16%), and the high noise levels (11%), and wanted these to change. Responses of the English sample on being shown the picture of the Indian coffee shop were as follows: almost all (95%) said they preferred their own coffee shop. More surprisingly, among the Indian hospital coffee shop attendees, all (100%) preferred their coffee shop.

Discussion

There were considerable differences between the English and Indian hospital coffee shops in their functions and views of their attendees. Despite the objective evidence, attendees at the Indian coffee shop rated it higher on cleanliness and all other parameters than did attendees in the English coffee shop. It is also worth noting that attendees at both hospital coffee shops preferred their own coffee shop when shown pictures of the other coffee shop.

It seems that hospital coffee shops mean much more to their attendees than merely a place to have a drink. Significant numbers (42% in India and 24% in England) used them as a venue to meet and talk to people, and to relax. This has important practical implications, as much more could be done to facilitate this highly valued function of hospital coffee shops. Yet another interesting difference was that those in India preferred to meet and talk to people (56%) but this was not so for those in England, suggesting a culturally determined social norm.

From a cross-cultural perspective, it was also interesting to note that attendees at both coffee shops preferred their local coffee shops to the one in the other country. This might indicate resistance to shift / change one’s cultural sets and attitudes. What seems appropriate in one culture might not be so in another and it would be ethno-centric to assume otherwise. Clinicians / psychiatrists and managers in today’s multi-cultural societies need to remember the cultural appropriateness of services offered to the very large number of ethnic minority patients and caregivers. Cultural sensitivity is key to developing psychiatric services that adequately meet the needs of a culturally diverse population. The key theme emerging from this study — the relative appropriateness and acceptability of services can vary across cultures — could inform development of culturally sensitive psychiatric services. To further extrapolate our findings to implications for psychiatric practice and service development, it could be inferred that it is not just the perceived quality or content of services (such as treatments, therapies, clinicians, etc.) that matter but also the settings and the cultural appropriateness and sensitivity of the form in which they are delivered.

Before drawing any generalisable conclusion from these findings, it is important to acknowledge some important limitations of our study. First, we recognise that our means of assessing respondents’ preferences for a hospital coffee shop in a particular setting as an indicator of reflecting patient preferences for a particular style of psychiatric service is indeed an indirect measure. Second, the design of the questionnaire and the subject area explored limit us to drawing only broad, but important conclusions. Third, we did not specifically attempt to address the possible heterogeneity of the attendees within the 2 settings. For example, their own degree of acculturation, place of birth, duration of years spent in the country, etc. It was the authors’ overall impression that most, if not all of those interviewed in the 2 countries, were native and locally born and raised, hence minimising the risk of attendees’ heterogeneity confounding the results.

Mr A was right after all when he said, “it’s not the same.” Hospital coffee shops in England and India are different. In both countries, hospital coffee shops seemed popular and served an important role as a setting for patient- visitor interactions and relaxation. In recognition of this important function of hospital coffee shops, much more could be done. Although this study only included hospital coffee shops in England and India, it is reasonable to argue that the findings are generalisable in different cultural settings.

Acknowledgements

We thank all those who participated in this study.

Reference

- Berger J. Seventh man. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1975.