Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2008;18:87-91

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

帕金森症狀與社區居住的車華裔老人微細功能衰退相關

Dr CWC Tam, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, Tai Po Hospital, Tai Po, New Territories, Hong Kong, China.

Dr VWC Lui, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, Tai Po Hospital, Tai Po, New Territories, Hong Kong, China.

Dr WC Chan, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Castle Peak Hospital, Tuen Mun, New Territories, Hong Kong, China.

Prof SSM Chan, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, New Territories, Hong Kong, China.

Prof LCW Lam, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, New Territories, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Cindy Tam, Department of Psychiatry, Tai Po Hospital, Tai Po, New Territories, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 2607 6731; Fax: (852) 2662 3568; E-mail: tamwoonchi@hotmail.com

Submitted: 21 February 2008; Accepted: 23 April 2008

Abstract

Objective: To report the prevalence of mild Parkinsonian signs and their association with functional impairment in a population-based study of clinically non-demented Chinese persons.

Participants and Methods: A random sample of 765 Chinese older persons from a thematic household survey was recruited. There were 389 normal elderly controls (Clinical Dementia Rating = 0), 291 with mild cognitive impairment, and 85 with very mild dementia. The prevalence of mild Parkinsonian signs and its association with everyday functional performance were investigated.

Results: Mild parkinsonian signs were defined as a score of 2 or more in the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale-motor section. The prevalence of mild parkinsonian signs was 16.5%, 33.0% and 49.4% in the normal controls, those with mild cognitive impairment and very mild dementia, respectively. In each group, subjects with mild parkinsonian signs had lower functional scores than those without such signs, even after adjusting for the effect of age, sex, and education. Abnormality in axial function, bradykinesia, and rigidity were associated with lower scores for Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, and rigidity was associated with lower Basic Activities of Daily Living scores.

Conclusion: The prevalence of mild parkinsonian signs increased with the severity of cognitive impairment in clinically non-demented older persons. Such signs were associated with functional impairment in older persons with mild cognitive impairment and very mild dementia.

Key words: Cognition disorders; Parkinsonian disorders

摘要

目的:本研究針對臨床上屬非痴呆的華裔長者,報告輕度帕金森症狀在這群長者中的普遍程度及其與日常生活功能缺損的關連。

參與者與方法:從一個主題性住戶統計調查中隨機抽樣765位華裔長者,其中389人認知正常的為對照組(臨床痴呆症評估量表分數= 0),291 人有輕度認知障礙, 85人有極輕度痴呆。研究探討了輕度帕金森症狀的普遍程度及其與日常生活功能的關係。

結果:在「統一帕金森病等級量表一動作評估」中,總分為2分或以上被定為有輕度帕金森症狀。在正常對照組、輕度認知障礙組和極輕度痴呆組,輕度帕金森症狀的普遍程度按序分別為16. 5% 、33. 0%和49.4%。針對年齡、性別、教育所致的效果作調整後,在各組中,有輕度帕金森症狀的日常生活功能得分較無帕金森症狀的要低。結果亦顯示,調節軸功能異常、動作遲緩和僵硬與工具性日常生活能力評定得分低相關,而僵硬又和基礎性日常生活能力評定得分低相 關。

結論:在沒有痴呆診斷的長者中,輕度帕金森症狀的現患率隨著認知功能受損程度而增加,而這些症狀與日常生活功能缺損有關。

關鍵詞:認知異常、帕金森症

Introduction

Mild parkinsonian signs (MPSs), which include rigidity, changes in axial function and resting tremor, occur in 15 to 50% of community-dwelling older people.1-3 Mild parkinsonian signs have been found to associate with cognitive decline, dementia, and mortality in non-demented elderly.4-6 Although these signs are mild, they are not prognostically benign.

It is widely held that disability in motor function is a late symptom of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).7 Yet, over the years, the presence of motor symptoms has been reported in moderate and mild AD.8-10 Several recent studies reported that MPSs were associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI)1,11,12 and increased risk of incident dementia.5,6 Mild cognitive impairment has been conceptualised as a transitional stage between normal ageing and early dementia.13 Subtle changes in daily function in MCI have attracted increased clinical attention.14,15 We hypothesised that MPSs were associated with functional impairment in older persons without clinical dementia, for instance, in MCI. Given the prevalence of these signs in older persons, MPSs as a potential indicator of disability should be further explored. In this study, we reported the prevalence of MPSs in a group of randomly recruited community-dwelling Chinese older persons in Hong Kong. Furthermore, the association between domains of MPSs and functional impairment in basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL) were explored and evaluated.

Methods

Participants

The study sample consisted of community-dwelling older persons who participated in a population survey for dementia conducted in Hong Kong. Detailed methodology of the survey was reported elsewhere.16 In summary, the study was conducted from October 2005 to July 2006. Phase 1 screening was conducted via the Thematic Household Survey commissioned by the Census and Statistics Department of the Hong Kong SAR. A total of 6100 persons aged 60 years and above were successfully screened in Phase 1. Participants who scored below the cutoff value were invited to Phase 2. In Phase 2, consenting subjects underwent an interview for diagnosis of dementia by an experienced psychiatrist. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Department of Health. Written informed consent was obtained independently for each subject in each phase.

The screening tools in Phase 1 comprised the Cantonese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (CMMSE),17 and a short memory questionnaire (Abbreviated Memory Inventory for the Chinese, AMIC).18 Three groups of subjects were invited for Phase 2 assessment. The first group consisted of subjects with CMMSE scores below the local cutoff for dementia (< 19 for illiterate persons; 20 for those with 1 to 2 years of education; and 22 for those with more than 2 years of education). The second group comprised subjects with CMMSE scores above the cutoff for dementia, but with significant memory complaints as evaluated by AMIC. The cutoff scores were determined in an independent sample of 396 community-dwelling Chinese elders. The third group consisted of 5% of a randomly selected screen-negative elderly subjects. Of 6100 subjects, 2073 (33.9%) failed the screening test and were considered as screen-positive; 737 (35.6%) agreed to have Phase 2 assessment. An additional group of 194 subjects from the screen-negative group were assessed as controls at Phase 2. The present study was based on information obtained from Phase 2 assessments.

Diagnostic Criteria for Cognitive Impairment

In Phase 2, the psychiatrist conducted an evaluation using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale.19 The CDR consists of a semi-structure interview (comprised 5 global ratings) to determine the diagnosis and severity of dementia. It entailed 6 sets of questions assessing different areas to form a global clinical impression. Subjects with a global score of 0 were classified as cognitively normal (NCs). Subjects with a global CDR of 0.5 were classified as having very mild dementia (VMD) if their memory and 3 or more boxes were rated as 0.5 or above.20 Subjects with a global CDR of 0.5 were classified as having MCI if their memory and less than 3 other CDR boxes were rated as 0.5. In the present study, data pertaining to the NC, MCI, and VMD groups were analysed.

Assessment

Parkinsonian Signs

Motor symptoms were assessed by the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale–motor section (UPDRS III).21 Mild parkinsonian signs were defined as present when any one of the following conditions was applicable11: (1) 2 or more UPDRS III ratings of 1, (2) 1 UPDRS III rating of 2 or higher, or (3) a UPDRS III resting tremor rating of 1. Mild parkinsonian signs were stratified into 4 subscales: axial function (changes in speech, facial expression, posture and gait), rigidity, tremor, and bradykinesia. An abnormality in UPDRS III subscale was considered present when the participants had either (1) UPDRS III ratings of 1 in 2 or more items of that subscale, or (2) 1 UPDRS III rating of 2 or higher.

Cognitive Function

Global cognitive assessments were estimated using the CMMSE and the Chinese version of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment scale–cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog).22 To test for episodic memory, subjects were examined using a 10- minute delayed recall of a word list from the ADAS-Cog.

Functional Assessment

Functional performance was assessed by the Chinese version of the Disability Assessment in Dementia (DAD).23 It evaluates instrumental ADL (IADL) and basic ADL (BADL) through the caregiver observations of the subjects’ actual performance in the previous 2 weeks. The DAD score was expressed as a percentage, with higher scores indicating better functioning. Apart from the total DAD score, the scores for BADL and IADL domains can also be analysed.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 11.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], United States). The demographic data, cognitive and functional measures were analysed using analysis of variance with a post-hoc Tukey HSD test. The Chi-square statistic was used to compare the frequencies of MPSs and individual MPS domains in different groups. The functional scores of subjects with and without MPSs were compared after adjusting for the effect of age, gender, and education. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to examine the effect of cognitive impairment, age, gender, education, and the scores of the 4 MPS subscales on the IADL and BADL scores.

Results

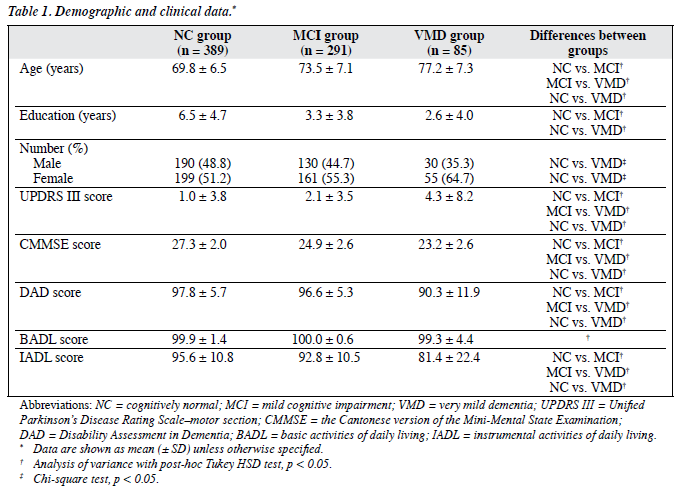

The sample size consisted of 765 subjects, with a mean age of 72.0 (standard deviation [SD], 7.3) years, and a mean of 4.8 (SD, 4.6) years of formal education. In all, 389 subjects belonged to the NC group, 291 to the MCI group, and 85 to the VMD group. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these subjects are summarised in Table 1. The MCI group had significantly better performance than the VMD group in CMMSE (post-hoc Tukey HSD test, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of ADAS-Cog and delayed recall test (post- hoc Tukey HSD test, p = 0.56 and p = 0.98, respectively). The mean scores for delayed recall in both the MCI and VMD groups were 1.5 SDs below that of the NC group.

There were significant differences in total DAD scores (F = 32.33, p < 0.001), IADL scores (F = 32.68, p < 0.001), and UPDRS III scores (F = 7.56, p = 0.001) among the 3 groups with different cognitive functions (after controlling for the effects of age, gender, and education). Gender and education did not contribute significantly to the variance of DAD, IADL, and UPDRS III scores. There was no significant difference in BADL scores among the 3 groups. In the whole sample, UPDRS III scores correlated negatively with CMMSE scores (r = –0.18, p < 0.001) after controlling for age and education.

Prevalence of Mild Parkinsonian Signs

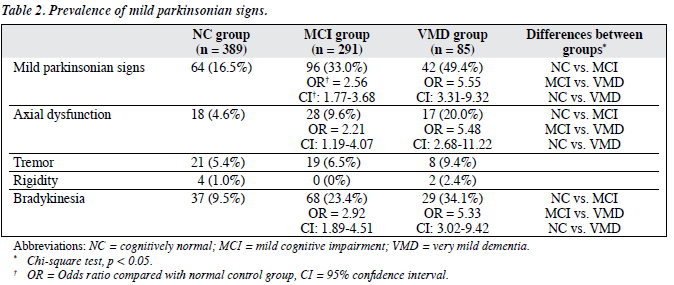

The prevalence of subjects with MPSs was 16.5%, 33.0% and 49.4% in the NC, MCI and VMD groups, respectively. Mild parkinsonian signs were more common in subjects with MCI (Chi-square statistics, odds ratio [OR] = 2.56) and those with VMD (Chi-square statistics, OR = 5.55) when compared with NC subjects. The most prevalent of these signs were bradykinesia and changes in axial function; both were present in a higher proportion of subjects with MCI and VMD than in NC subjects. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of tremor and rigidity among the 3 groups. Four subjects in the NC group, 2 in the MCI group, and 1 in the VMD group had a known diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. The prevalence was about 1% (Table 2).

Functional Impact of Mild Parkinsonian Signs

After adjusting for the effect of age and education in each group, subjects with MPSs had significantly lower DAD scores than those without MPSs (ANCOVA, F = 15.91, p < 0.001 for NC group; F = 7.32, p = 0.01 for MCI group; F = 17.01, p < 0.001 for VMD group).

The ANCOVA was performed to examine the effect of the diagnostic group, which reflected the level of cognitive impairment, age, gender, and education and the scores of the 4 MPS subscales on the IADL and BADL scores. The diagnostic group (F = 17.50, p < 0.001), abnormality in axial function (F = 9.24, p = 0.002), rigidity (F = 6.20, p = 0.01), and bradykinesia (F = 18.99, p < 0.001) all contributed to the variance of IADL scores. Rigidity (F = 192.82, p < 0.001) contributed to the variance of BADL scores.

Discussion

The association of MPSs with both MCI and clinical dementia has been demonstrated in previous studies.4-6,11,12 Our study reported that MPSs were 2.5 to 5.5 times more common in community-dwelling Chinese older people with MCI and VMD. Mild parkinsonian signs remained more common in the MCI and VMD groups after accounting for age, gender and education, which suggests that MPS seems to be a common phenomenon in older persons with subtle cognitive impairment in different ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Axial dysfunction and bradykinesia were more common than rigidity and tremor in the subjects with MCI and VMD. This result was similar to the observations that bradykinesia and gait disturbance were more frequent extrapyramidal signs in the patients with MCI and AD.8,12

The prevalence and severity of MPSs increased as the severity of global cognitive impairment increased. Louis et al1 reported a prevalence of MPSs of 22.0% in older people with amnestic MCI and 15.7% in those without MCI. The prevalence of subjects with MPSs was comparable in our NC subjects, even after we excluded those with a known history of stroke and Parkinson’s disease. However, higher prevalence of subjects with MPSs was reported in our MCI subjects compared to that in Louis et al’s study.1

These differences might be due to the adoption of different definitions of MCI, and some of our subjects having undiagnosed silent stroke, Parkinson’s disease or Parkinsonism plus syndrome, or in receipt of antipsychotic medications. Moreover, we included the assessment of appendicular bradykinesia in our motor assessment, while it was not included in the modified UPDRS III in Louis et al’s study.1

Subjects with MCI and VMD had subtle but significant impairment in functional performance compared with those in the NC group, which was consistent with previous studies.14,15 Our results also supported the association of MPSs and functional impairment in clinically non-demented older persons (after adjusting for age, gender and education). Our results suggest that different domains of MPSs have differential patterns of influence on daily functioning. The abnormality in axial function, bradykinesia, and rigidity were independently associated with functional impairment in IADL, while rigidity was associated with impairment in BADL. Louis et al1 also suggested that axial dysfunction and rigidity were associated with functional disability in MCI subjects.

One limitation of our study was that it was cross- sectional. Further prospective study is needed to elucidate the causal relationship. Future clinicopathological studies are needed to investigate the underlying mechanism or shared pathogenesis of cognitive impairment and parkinsonian signs.

The strengths of our study were that we recruited a random sample of community-dwelling older persons and used standardised assessment for cognitive, functional and motor assessment. Given the high prevalence of these signs and the association with functional impairment in older persons, MPSs could be a significant indicator of disability in elderly persons. A prospective study is needed to assess the functional consequences and prognostic value of parkinsonian signs in predicting incident dementia.

Acknowledgements

The project is supported in part by the Mr Lai Seung Hung & Mrs Lai Chan Pui Ngong Dementia in Hong Kong Research Fund, and an educational fund from Eisai. We are thankful to the Novartis and AstraZeneca for their sponsor of souvenirs for the participants. Finally, we are also grateful to the social centres for their assistance in the Phase 2 assessment.

References

- Louis ED, Tang MX, Schupf N, Mayeux R. Functional correlates and prevalence of mild parkinsonian signs in a community population of older people. Arch Neurol 2005;62:297-302.

- Louis ED, Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Mayeux R. Parkinsonian signs in older people: prevalence and associations with smoking and coffee. Neurology 2003;61:24-8.

- Bennett DA, Beckett LA, Murray AM, Shannon KM, Goetz CG, Pilgrim DM, et al. Prevalence of parkinsonian signs and associated mortality in a community population of older people. N Engl J Med 1996;334:71-6.

- Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Parkinsonianlike signs and risk of incident Alzheimer disease in older persons. Arch Neurol 2003;60:539-44.

- Louis ED, Tang MX, Mayeux R. Parkinsonian signs in older people in a community-based study: risk of incident dementia. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1273-6.

- Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Motor dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1763-9.

- Cummings JL. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. In: Cummings JL, Miller BL, editors. Alzheimer’s disease: treatment and long-term management. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1990:3-19.

- Lopez OL, Wisnieski SR, Becker JT, Boller F, DeKosky ST. Extrapyramidal signs in patients with probable Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1997;54:969-75.

- Goldman WP, Baty JD, Buckles VD, Sahrmann S, Morris JC. Motor dysfunction in mildly demented AD individuals without extrapyramidal signs. Neurology 1999;53:956-62.

- Pettersson AF, Olsson E, Wahlund LO. Motor function in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2005;19:299-304.

- Louis ED, Schupf N, Manly J, Marder K, Tang MX, Mayeux R. Association between mild parkinsonian signs and mild cognitive impairment in a community. Neurology 2005;64:1157-61.

- Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, Arvanitakis Z, Kelly J, Bienias JL, et al. Parkinsonian signs in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2005;65:1901-6.

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 2004;256:183-94.

- Perneczky R, Pohl C, Sorg C, Hartmann J, Komossa K, Alexopoulos P, et al. Complex activities of daily living in mild cognitive impairment: conceptual and diagnostic issues. Age Ageing 2006;35:240-5.

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, Cahn-Weiner D, Decarli C. MCI is associated with deficits in everyday functioning. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:217-23.

- Lam LC, Tam CW, Lui VW, Chan WC, Chan SS, Wong S, et al. Prevalence of very mild and mild dementia in community-dwelling older Chinese people in Hong Kong. Int Psychogeriatr 2008;20:135- 48.

- Chiu HF, Lee HC, Chung WS, Kwong PK. Reliability and validity of the Cantonese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination — a preliminary study. Journal of Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists 1994;2:25-8.

- Lam LC, Lui VW, Tam CW, Chiu HF. Subjective memory complaints in Chinese subjects with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:876-82.

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982;140:566-72.

- Storandt M, Grant EA, Miller P, Morris J. Rates of progression in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2002;59:1034-41.

- Stern MB. The clinical characteristics of Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonian syndromes: diagnosis and assessment. In: Stern MB, Hurtig HI, editors. The comprehensive management of Parkinson’s disease. New York, NY: PMA Publishing Corp; 1978:34-9.

- Chu LW, Chiu KC, Hui SL, Yu GK, Tsui WJ, Lee PW. The reliability and validity of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog) among the elderly Chinese in Hong Kong. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2000;29:474-85.

- Mok CC, Siu AM, Chan WC, Yeung KM, Pan PC, Li SW. Functional disabilities profile of Chinese elderly people with Alzheimer’s disease — a validation study on the Chinese version of the disability assessment for dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2005;20:112-9.