J.H.K.C. Psych. (1993) 3, 39-42

SPECIAL TOPIC: CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

Summary

The characteristic of 200 children attending the Centre of Marriage and Child Guidance during a 12-month period in 1990 are examined. The implications for service provision are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The Centre of Marriage and Child Guidance was inaugurated in February, 1985 and registered as a charitable organization since 1st July, 1988. It is run by a group of Christian medical doctors and related professionals with the aim of providing holistic counselling services to individuals, couples, children and families. In the area of child guidance, the Centre provides assessment and therapy to children with developmental, behavioral, emotional and learning problems. In the year of 1990, the Centre was staffed with 2 part-time psychiatrists, 3 part-time clinical psychologists, 2 part-time educational psychologists, 1 part-time speech therapist, 1 part-time counsellor and 1 part-time occupational therapist. The Centre's service is open to the public, accepting self-referrals and referrals from professionals and organizations. Although the Centre has a Christian background, our clientele does not show a predominance over the Christian faith. Fees are charged according to the nature of service requested. The Centre is self-financing and non-profit making.

The characteristics of children attending child guidance and child psychiatric clinics have been studied in the U.K. (Thomas and Hardwick, 1989, Thompson and Parry, 1991). Similar studies have been performed in Hong Kong (S.C.L. Chen, 1986; Chung, Luk & Soo, 1991). The study by Chung, Luk & Soo supported the need for self-referred specialist service by a child mental health clinic.

The aims of the present study are:

- to examine the characteristics of children attending the Centre of Marriage and Child Guidance;

- to compare the present findings with those of the previous studies; and

- to suggest implications for future services

METHOD

All the child cases (16 years and under) seen at the Centre from January 1, 1990 to December, 31, 1990 were in- eluded as subjects in the present study. The referral patterns and case characteristics were coded from a standardized intake form and the case notes by one of the Centre's staff, who was an occupational therapist.

RESULTS

PATTERN Of REFERRAL

Source of Referral

By far, the majority of cases (25%,, N = 200) were referred by friends and relatives. 22.5% were referred by medical doctors, 20% were from social service agencies, 12.5% from schools (including nurseries and kindergartens), and 6.5% self-referred.

Monthly Referral Rate

The peak of the referrals (26.5'X, ) came in the summer months of June & July. The Centre did not keep any waiting list, and new cases were seen within 1-2 weeks' time upon referral.

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

Sex and Age

200 children under the age of 16 were seen during the 12-month period. The mean age of children referred was 7.1 years (S.D: 3.91). The median age was 6.5 years. The 2-5 years old constituted 34% of the cases seen. Another main bulk of cases (39°/.,) fell between the age of 6-11. The 12-13 year age group formed another peak of referrals (7.5%). 75.5% of the cases were boys and 24.5% of them were girls.

Birth order of Child-in-question

58% of the children referred were the first born in the family, of these 20% came from single child families.

Structure of family

An over whelming majority, i.e. 186 (93% ) of the 200 cases came from intact families. 6 came from reconstituted families, 2 from single parent families and 6 unknown.

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

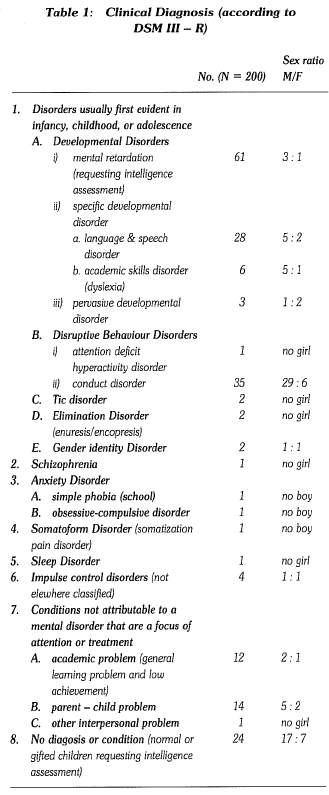

The breakdown of the clinical diagnosis is presented in Table 1.

Mental retardation and other cases requiring intelligence assessment formed the main request (42.5%} among all the referrals. Language and Speech problems (14%} came next. Conduct disorders such as stealing/lying/fighting and aggression were another main cause for seeking child guidance (17.5%}. Parents were seeking advice on their parenting skills and improving their relationship with their children (parent-child problems 7%}. In addition, academic problems such as general learning problems and low achievement are also the focus of the parents' attention (6%).

PATTERN OF ATTENDANCE

Parents at the first interview

The mother is still the major primary person responsible for the child's welfare. Only 11.5% were not accompanied by their mother at the first interview. About 19% of the father showed up at the first interview.

Total No. of interviews attended

56.5% of all the 200 cases only attended the centre once, of which 42.5% came for intelligence assessment. 25% came for 2 to 3 sessions. 18.5% of cases attended 4 or more sessions. 11 cases attended more than 10 sessions and 2 cases are still attending at the time of this study, i.e. after 2 years. There are a total of 7 default cases which represented 3.5% of all the cases where follow-up treatment was originally planned.

Therapist's discipline at the first interview

162 (81%} of all the 200 cases were attended to by psychologist at their first interview, 26 cases (13%} by speech therapist, 6 cases by psychiatrist, 5 cases by occupational therapist and 1 case by counsellor.

Clients can make their own choice about who they would like to see at the time they make their first appointment over phone. If they have no preference about the therapist's discipline, they would normally be seen by a clinical psychologist. After the first interview, cases would be referred to the other experts in the team for further assessment or therapy.

DISCUSSION

The source of referrals probably reflected the administration pattern and networking of the child guidance centre/ clinic concerned. In a U.K. study reported by Thomas and Hardwick (1989), the majority of cases (79%} referred to a small child psychiatric clinic are from general practitioners and hospitals. However, in a study similar to the present one conducted in Hong Kong by Chung, Luk, & Soo (1989), 81% of the cases referred to the child mental health clinic were self-referred, and these non-screened cases were considered as serious enough to deserve psychiatric intervention. In the present study, a total of 34.5% of the cases approached the Centre without any referral from any agencies. They knew the service through either their friends, relatives, or the mass media like the newspaper where the Centre was the contributor of special features on child issues. In Hong Kong, direct specialist services for children were rare, if not absent.Psychological service, speech therapy services, or occupational therapy services often are only available with referrals and long waiting periods are required.

The mean age of the children seen in the present study was 7.1 years, whkh was about 1 year younger than the study by Chung, Luk & Soo (1989) (mean age 8 years 2 months). This differs from the studies reported in the U.K. by Thomas & Hardwick (1989) in which the majority of the referrals were adolescents, In the study by Thompson & Parry, (1991) conducted in the U.K., the mean age was 11 years. The two main bulk of cases seen were the 2-5 year olds as well as the 6-11 year olds. The first peak could be considered as at 2-3 years and the second peak at 6-7 year old. Pre-school children, upon starting their nursery school at the age of two to three, were often detected by parents or kindergarten/nursery teachers to have problems. As the child leaves pre-school and enters primary school, at the age of six to seven, there occurs another surge of problems. Much younger children were brought to speicalist's services by local parents. This is a good sign if we view it from the point of early detection and intervention, and destigmatization of child guidance services. Similar to the findings found in other studies (Chung, Luk & Soo, 1989; Thomas & Hardwick, 1989; Thompson & Parry, 1991), the majority of the cases in the present study, were boys 75.5%, 70% and about 60% were respectively reported by the other studies. (Chung et. al, 1989, Thomas et. al, 1989, Thompon et. al, 1991). The provision of psychological assessment and speech therapy services may also account for the reason for the young age of the children in the present study. Boys predominatd over all the age groups, with the exception at the 11-12 year age group, where an equal split occurred. About 42.5% of all the cases requested intelligence assessment. Conduct problems and learning related problems ranked the 2nd and 3rd on the list of problems. If not for the presence of psychologists in the Centre where assessment could be performed, the present pattern would be similar to that reported by Luk et. al, (1989) where conduct problem and school performance formed the majority of the reasons for referral. Emotional and mood problems did not constitute the primary reasons for referrals. School difficulties only constitute a neglible 0.9% in the study reported by Thomas et. al in the U.K.

All the cases paid fees for the services they received and they were voluntary clients. As the Centre is self-financing, the fees charged are much higher than that of the government which is considered as nominal. Almost all came from intact families (93%) and about 19% of the fathers were involved in bringing the children to attend the first session. The majority of cases had only a very brief contact with the Centre. 82.5% the cases attended 1-3 sessions only. In the study by Thomas et. al, (1989), 65% of the families only came for 3 sessions or under. Similarly, brief contact therapy was reported in the study reported by Thompson et. al, (1991). In the present study, the % of short-term contact was even higher.

Analysis of the one session cases revealed that the majority were cases requesting for intelligence assessment for placement, immigration or other purposes. Only 1% of the cases were still attending the Centre after 2 years.

CONCLUSION

An audit of our cases helps us to know our clients' needs and how we can meet them better. Parents are requesting specialist services for their children at a young age. Intelligence and academic related problems are their primary concern, followed by their children's conduct and behaviour. Brief therapy is expected and the mother is still the primary person responsible for the child's welfare, although we are glad to see one fifth of the fathers participate in bringing their children to see the specialists. Boys are the more vulnerable group.

REFERENCES

Chung, S.Y., Luk, S.L., & Sao, J. (1991) Characteristics of children Attending a Primary Care Psychiatric Clinic. Journal of the Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists 1, 47-49.

Thomas, H.J. & Harwick, P.F. (1989) An Aduit of a Small Child Psychiatry Clinic. Newsletter Association for Child Psychology and Psychiatry 11, 10-14.

Thompson, M.F.F. & Parry, G. (1991) A Comparative Audit of Referrals to a Child Guidance Clinic 1981-1987. Vol 13, 15- 23.

Chen, C.L. (1986) Child Psychiatric Cases attending a Government Psychiatric Out-Patient Clinic Over Six years. Mental Health in Hong Kong, 1986. Mental Health Association of Hong Kong, 107-119.

L.K.Chung B.Soc.Sc., M.Soc.Sc. Clinical Psychologist, Centre of Marriage and Child Guidance, 10/F., Breakthrough Centre, 191, Woosung Street, Kowloon, Hong Kong.