Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry (1995) 5, 5-17

SPECIAL TOPIC: FORENSIC PSYCHIATRY

Summary

The issue of Patient’s Consent is a complex matter, with numerous factors requiring consideration. In this paper, these factors are discussed in detail one by one. In addition, 2 algorithms have been drawn up for the guidance of the Clinician in how to make up his decision during his day-to day practice.

Keywords: consent, treatment, investigation, research

THE FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPT ---"RESPECT FOR AUTONOMY"

Faden & Beauchamp (1986) summarised the concept as such : "'Autonomy 'and 'respect for autonomy' are terms loosely associated with several ideas, such as privacy, voluntariness, self-mastery, choosing freely, the freedom to choose, choosing one’s own moral position, and accepting responsibility for one’s choices… The moral demand that we respect the autonomy of persons can be formulated as a principle of respect for autonomy. Persons should be free to choose and act without controlling constraints imposed by others. The princi ple provides the justificatory basis for the right to make autonomous decisions, which in turn takes the form of specific autonomy-related rights."

Consent then is much more than a medicolegal concept, as it encompasses a number of moral precepts relating to freedom of choice and the right to decide whether or not to accept advice and treatment.

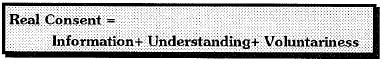

COMPONENTS OF A VALID CONSENT

The Department of Health and Welsh Office (1990) have proposed a helpful definition of consent, which is: "the voluntary and continuing permission of the patient to receive a particular treatment, based on adequate knowledge of the purpose, nature, likely effects and risks of that treatment, including the likelihood of its success and any alternatives to it."

INFORMATION

There is more to consent than getting a patient's signature on a consent form. In seeking consent the doctor is required to provide sufficient details and infom1ation about what is proposed to enable the patient to form a proper decision. Misinformed consent or consent given without proper understanding of what is involved is of little legal value. Whilst it might protect against allegations of assault or battery, it would not afford a defence against allegations of inadequate counselling or failure to warn.

The extent of the explanation which the doctor should give when seeking consent will depend on many factors and may pose considerable problems, calling for fine clinical judgment. Factors to be taken into account include the patient's age and maturity, physical and mental state, intellectual capacity and the reason for the procedure, operation or treatment. For example, a routine cosmetic procedure may need to be discussed far more extensively than an emergency operation for a life-threatening condition in an ill patient. The explanation which the doctor gives will also depend upon the questions the patient asks, some patients requiring to know far more than others about side-effects, complications etc. A careful and truthful answer must be given to a particular request by a patient for information.

English law has rejected the doctrine of "informed consent", and instead merely requires that the patient knows in broad terms what he is consenting to {Mackay, 1990), As a matter of fact, patients may be put at 1isk by being given so much information that they refuse necessary treatments (Heneghan, 1991).

Two dicta are particularly relevant. The first is by Lord Templeman (1979):

A patient may make an unbalanced judgment because he is deprived of adequate information. A patient may also make an unbalanced judgment if he is provided with too much information and is made aware of possibilities which he is not capable of assessing because of his lack of medical training, his prejudices or his personality ... At the end of the day, the doctor, bearing in mind the best interests of the patient and beating in mind the patient's right to information which will enable the patient to make a balanced judgment, must decide what information should be given to the patient and in what terms that information should be couched.

In the second dictum Lord Scarman ( 1981) said: 'And it is plainly right that a doctor may avoid liability for failure to warn of a material risk if he can show that he reasonably believed that communication to the patient of the existence of the risk would be detrimental to the health (including of course the mental health) of his patient'. It is clear, therefore, that a doctor has something in the nature of a 'therapeutic privilege' relating to the non-disclosure of material risks. The exercise of th.is p1ivilege is available provided the doctor has made a reasonable decision that to inform his patient of the risks would be positively prejudicial to his mental or physical health.

However, it is submitted that a blanket decision not to disclose material risks merely because the patient is considered to be incapable of making a 'balanced' judgment should not of itself relieve the physician from attempting a simple straightforward explanation unless such an explanation is of itself considered detrimental to health. Each individual case will of course turn on its own facts.

UNDERSTANDING = MENTAL COMPETENCY

As a rule of thumb, this can be assessed by checking whether the patient knows, "in broad terms", all of the followings: (a) What, (b) How, (c) Consequences, & (d) Why. In other words, he knows what he is consenting to, he knows how to convey his consent (oral, written, or implied by his actions), he knows the consequences of giving or refusing the consent, and he can give a rational reason for his consent or refusal. (Thus, a patient who refuses an operation because he thinks the surgeon is part of his persecutory delusion is mentally incompetent to give the consent, even though he is fully cognizant of the What, How & Consequences. However, if the patient refuses the treatment because of some cultural, religious, or socially understandable reason, however idiosynoratic it may appear to the doctor, this patient may still be regarded as mentally competent.)

The Level of Competency Expected by Society in general is Not High.

As already noted, English law has rejected the doctrine of 'informed consent' and instead merely requires that the patient 'knew in broad terms what he was consenting to'. It follows from this that 'if only a "broad terms" explanation is required in order for consent to be "real", the corollary should be that the patient is capable of giving such consent if he is capable of understanding such a "broad terms" explanation' (Haggett, 1984, p.196). As a result, the English approach may in fact 'help to preserve the autonomy of some mental patients, particularly those who are mildly mentally handicapped', for such patients are much more likely to be able to give 'real' consent to the recommended treatment and also to refuse their consent (Haggett, 1984).

Competency of a person is not All-or-None; it depends on the complexity of the task in question.

A patient may be mentally competent to give consent for a simple dressing to a visible wound, but hardly competent to do the same for a complex surgery involving multiple organs and a delicate balance of benefits and risks.

Refusing to give Consent requires a higher level of competency than merely giving consent.

The consequences of withholding consent to treatment are usually much more significant and potentially dangerous than simply giving consent - unless one believes that most treatments are either unnecessary or are likely to be more dangerous than the condition for which they were prescribed. Refusal to consent to treatment suggests that the patient has knowledge or beliefs that conflict with expert medical advice. Thus it can be argued that refusing to give consent is a higher order of decision-making than merely giving consent (MaCall-Smith, 1992). A more stringent test should therefore be applied when assessing a person's ability to refuse consent than when assessing competence to consent. Some pointed to the "Catch 22" created - patents whose competence is in question are found rational and able to give consent if they accept the advice of the doctor; but are judged incompetent if they reject that same advice (Devereux et al, 1993).

Serious Decisions require a Higher Level of Competency than Less Serious Decisions.

People in our society might agree with those like Professor J. F. Drane (1985) who proposes that required standards of "competence" to make decisions on medical care for oneself should vary with the seriousness of those decisions. Thus to be respected as competent to make decisions that are "very dangerous and run counter to both professional and public rationality"- for example, a decision to refuse lifesaving treatment- would require a far higher standard of manifest competence to make informed, voluntary, deliberated, and thus autonomous decisions than would less dangerous decisions, including a decision to accept the same treatment (Eth, 1985).

Competency is not a Fixed State.

English law, unlike many other jurisdictions including in particular the United States {Brakel et al 1986), has no legally recognised competency hearings in relation to either detention (under the Mental Health Act 1983) or treatment without consent. There is good reason for this since 'competency is not necessarily a fixed state that can be assessed with equivalent results at one of a number of times. Like the patient's mental status as a whole, a patient's competency may fluctuate as a function of the natural course of his or her illness, response to treatment, psychodynamic factors... metabolic status, intercurrent illnesses, or the effects of medication' (Applebaum & Roth, 1981). In consequence, a determination of a patient's general incompetency has no special legal significance, although clearly it may be highly influential from a practical point of view in reaching a decision as to whether detention as an inpatient is required. By the same token neither does a determination of special incompetency relating to consent to treatment have any particular legal status.

VOLUNTARINESS

When force, fraud, coercion, duress, undue influence, deceit, constraint, mistake or deception are present (Someurille, 1980), this is not true consent.

However, the decision is not always clear-cut. Clearly, an agreement to participate in some clinical trial would hardly be voluntary if the "volunteer" and his family were threatened with death if he refused. But what about an offer of payment? Most of our decisions are subject to some degree of external pressure. At one end of the spectrum such pressures are clearly powerful enough grossly to impair our autonomy of will or intention; at the other end they are equally clearly within the normal range of "pros and cons", consideration of which necessarily plays a part in voluntary choice.

In situations such as inside a prison, where the coercion may be subtle and covert, the clinician has to be particularly careful when more risky procedures are being consented to.

LEGAL LIABILITY: BATTERY OR NEGLIGENCE

The common law has developed in such a way as to give a patient two possible causes of action surrounding the absence of consent or lack of information relating to consent. The first is battery, the second an offshoot of the tort of negligence.

According to Robert Goff L J in Collins v Wilcock( l984), "Battery is the infliction of unlawful force on another person. The fundamental p1inciple, plain and uncontestable, is that every person's body is inviolate. It has long been established that any touching of another person, however slight, may amount to a battery .... The effect is that everybody is protected not only against physical injury but against any form of physical molestation". Liability to Battery presupposes no consent whatsoever (Skegg 1984). For example, in the case of Odam v Young (1955), a 15- year-old boy who was sent by his parents to accompany his younger brother to a clinic where the latter was to receive an injection, was also injected, against his will. The court had no difficulty in concluding that on these facts the tort of battery had been committed.

Negligence, on the other hand, is applied where the doctor has already got the general consent of his patient before he begins treatment, and he fails to execute his duty adequately, such as his duty to disclose important information before obtaining consent. In the words of Lord Fraser in the famous case of Whitehouse v Jordan (1981) : "The true position is that an error of judgment may, or may not, be negligent; it depends on the nature of the error. If it is one that would not have been made by a reasonably competent professional man professing to have the standard and type of skill that the defendant held himself out as having, and acting with ordinary care, then it is negligent. If, on the other hand, it is an error that a man, acting with ordinary care, might have made, then it is not negligence". In Maynard v West Midlands Regional Health Authority (1985), Lord Scarman added : "It is not enough to show that there is a body of competent professional opinion which considers that theirs was a wrong decision, if there also exists a body of professional opinion, equally competent, which supports the decision as reasonable in the circumstances. It is not enough to show that subsequent events show that the operation need never have been performed, if at the time the decision to operate was taken it was reasonable in the sense that a responsible body of medical opinion would have accepted it as proper I would only add that a doctor who professes to exercise a special skill must exercise the ordinary skill of his specialty. Differences of opinion and practice exist, and will always exist, in the medical as in other professions. There is seldom any one answer exclusive of all other to problems of professional judgment. A court may prefer one body of opinion to the other, but that is no basis for a conclusion of negligence."

WHERE "RESPECT FOR AUTONOMY" IS NOT THE ANSWER

Although I have emphasized the centrality of the principle of Respect for Autonomy, there are clinical circumstances in which Respect for Autonomy does not seem to be the most important or relevant moral principle. They include examples in which patients have given prior consent for their doctors to make decisions on their behalf; in which respect for the autonomy of a particular patient conflicts with respect for the autonomy of others or causes harm to others or conflicts with considerations of justice; in which the patient has either no autonomy or too little autonomy for the principle of respect for autonomy to apply; and of emergencies in which it is not possible to find out what the patient himself would wish to happen.

Often patients positively and deliberately delegate doctors to make decisions and manage their case. Provided the patients have made an autonomous choice then the doctor who accedes to their request and makes the decisions is indeed respecting their autonomy. In these circumstances the Hippocratic principles of medical beneficence and non-maleficence to the patient are the main moral determinants, though they may have to be constrained by considerations of justice.

A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR CLINICIAN

Clinicians, psychiatrists or non-psychiatrists, often have to face various practical issues concerning consent to various medical procedures. Here I have drawn up 2 algorithms, 1for minor patients and 1 for adult patients for the clinicians' practical guidance (see Algorithms 1and 2). I shall further elaborate on the salient points in the 2 algo1ithms in the rest of this paper.

PATIENTS INVOLUNTARILY DETAINED UNDER MHO

WHO ARE THE DETAINED PATIENTS ?

This category of patients are at present detained only in 2 kinds of places, viz. (a) Mental Hospitals declared as such in the government gazettes (currently Castle Peak Hospital, and some wards of Kwai Chung Hospital and Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital), and (b) Psychiatric Centre in the Correctional Services Department (CSD) (currently Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre).

Voluntary patients in Mental Hospitals, and informal mental patients outside Mental hospitals are not in this category. (For the purpose of the present topic, voluntary and informal patients may be regarded as identical.).

Some mental patients are involuntarily detained in Mental Hospitals or CSD Psychiatric Centre under the

Criminal Procedure Ordinance. However, these patients are treated in the eyes of the Law as if they are admitted under the Mental Health Ordinance.

LEGAL POSITION OF DETAINED PATIENTS

Once a person has been lawfully detained under the Mental Health Ordinance, the legal position relating to consent to treatment changes dramatically. The first and most important point is that the patient's consent is not generally required for any medical treatment for mental disorder. Thus, although it may and should be good medical practice to obtain, wherever possible, a detained patient's 'real' consent to treatment for the mental disorder from which he is suffering, this is no longer a legal requirement. In short, a patient's common-law right to refuse treatment, including the protection of the tort of battery, has been eclipsed. Thus, although the patient may be quite competent, and the mere fact of his detained status is no indication to the contrary, then his refusal to accept treatment so long as it is for his mental disorder may be, at worst, ignored and over-ridden. The only qualification is that the decision to treat without consent must not be reached in bad faithor without reasonable care.

The Mental HealthAct (1983) of UK has a specific Part IV which deals with "Consent to Treatment" and stipulates the legal requirements in relation to specific psychiatric treatments, including psychosurgery, surgical implantation of hormones to reduce male sexual drive, electroconvulsive therapy, medication for more than 3 months, 'urgent' treatments, etc. The Mental Health Ordinance of Hong Kong does not have such a specific Section. Nevertheless, I have modelled my algorithm along the spirit of the Mental Health Act of UK.

However, it must be borne in mind that the provisions of the Mental Health Act cover only treatment for mental disorders or for physical conditions causing/contributing to the mental disorders, but do not cover treatment for any other physical conditions.

In its Draft Code of Practice, the Mental Health Act Commission(1985) states :

"If however the proposed treatment for a 'refusing' patient is for a physical condition which is neither causing nor contributing to the mental disorder, (even if it is caused by, or contributed to by, the mental disorder), the following principles of good practice should be observed.

No treatment can be given under the Mental Health Act because the treatment is not 'for' mental disorder.

If the treatment can properly be deferred, an opportunity or opportunities should be given for the patient to change his mind. If the treatment cannot be deferred, or if the patient does not change his mind, the following

principles should apply: If the physical condition is a serious one, or is causing or is likely within the near future to cause pain or distress, and if the doctor's view is that the patient's 'refusal' to have the treatment is the result of his mental disorder, the treatment may be given .

If however it is clear that the patient's refusal is not the result of his mental disorder, but is the result for instance of religious or cultural views, the refusal should be respected and the treatment not given."

COMPULSORY TREATMENT IN THE COMMUNITY (IN NON-EMERGENCY SITUATION)

The Mental Health Ordinance allows compulsory treatment in community by the following Sections :

Section 34 (Guardianship) :confers on the guardian "the power to require the patient to attend at places and times so specified for the purpose of medical "

Section 39 (Absence on Trial): "A medical superintendent may from time to time permit a certified patient or a patient under observation to be absent from the mental hospital on trial for such periods as the medical superintendent may think proper. Any absence on trial under this section shall be subject to such conditions as the medical superintendent may "

c) Section 42B (Conditional discharge of patients with propensity to violence) : may require the conditionally discharged patient "to attend at an out-patient department of a hospital or at a clinic specified by the medical superintendent" and "to take medication as prescribed by a medical "

Patients who contravene the above 3 Sections may be liable to be admitted to a mental hospital.

AGE OF CONSENT

Another issue often encountered is the age for consent. Each case must be carefully considered on its own merits, but the general situation can be summarised as in Table 1.

It can thus be seen that the minors (i.e. below age 18) are sub-divided into 2 groups using the age of 16.

MINORS BELOW AGE 16

Here the position remains governed by the common law and is subject to the decision of the House of Lords in Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority and another (1985), where it was held that a girl under 16 years old did not, merely by reason of her age, lack legal capacity to consent to contraceptive advice and treatment by a doctor. Although this case related exclusively to the issue of contraceptive advice and treatment, there seems no reason to suppose that the decision should not be applied to other forms of treatment, including that required for mental disorder. Indeed, the following statement by Lord Scarman (1981) is clearly wide enough to encompass this :

"I would hold that as a matter of law the parental right to determine whether or not their minor child below the age of 16 will have medical treatment terminates if and when the child achieves a sufficient understanding and intelligence to enable him or her to understand fully what is proposed. It will be a question of fact whether a child seeking advice has sufficient understanding of what is involved to give a consent valid in law. Until the child achieves the capacity to consent, the parental right to make the decision continues save only in exceptional circumstances. Emergency, parental neglect, abandonment of the child or inability to find the parent are examples of exceptional situations justifying the doctor proceeding to treat the child without parental knowledge and consent; but there will arise no doubt, other exceptional situations in which it will be reasonable for the doctor to proceed without the patient's consent."

The right of the minor, therefore, to consent to treatment depends entirely on his intellectual capacity to understand what is proposed. If he has this capacity then the normal legal requirements of obtaining 'real' consent along with the duty to disclose information apply equally to him. If on the other hand a minor of whatever age lacks capacity to consent, then the parents must be approached in order that they may consent on the child's behalf. Should the parents unreasonably refuse to consent, then the solution may be in wardship proceedings thus allowing the court to authorise treatment (Re B: a minor (1987)).

MINORS OF AGE 16 OR OVER

In Hong Kong, the Mental Health Ordinance (Cap 136) allows a minor who has attained the age of 16 to become a voluntary patient of a mental hospital by his own accord. With regard to treatment, an analogous provision was enacted by the Family Law Reform Act 1969, s. 8(1) of

- which provides that once 16, a minor's consent to 'any surgical, medical or dental treatment ... shall be as effective as if he were of full age'. The combined effect of these statutory provisions is to ensure that the competent 16- or 17-year-old may lawfully become a voluntary patient and may lawfully consent to treatment for both mental and physical

Having said this, however, one very fundamental difference between a minor of age 16-17 and a major of age 18 or above can be seen in rulings at the Court of Appeal by Lord Donaldson (re R, 1991; re W, 1992). In both cases the Judge ruled that young people under the age of 18 years have no absolute right to give or refuse consent to treatment. Parents, local authorities and others with parental responsibilities also have the right to give and refuse consent. This means it is possible for a 17-year-old who has sufficient understanding of the issues, and is therefore 'Gillick competent', to refuse treatment and then be overruled by the teenager's parents, the local authority or the court.

HOW TO ASSESS COMPETENCE OF A CHILD ?

It makes little sense to have a magic age when children suddenly become competent to give consent. A number of factors must be taken into account when assessing a child's ability to consent to treatment. The central issue concerns the child's stage of cognitive development. In order to give valid consent, children must have reached the stage of maturity where they have a clear concept of themselves in relation to other people, including an ability to recognise their own needs and the needs of others. Competent children will have an ability to understand the nature of their disorder and know why treatment is deemed to be necessary. They should be able to understand the significance of the risks and benefits of having or not having the treatment. In addition, the competent child will be able to understand these issues in relation to the passage of time and be fully aware of what might happen in the future as a result of having or foregoing the treatment. Most children below eight years of age have not yet developed a good understanding of time, nor have they gained a clearly defined self-concept. It is hence inappropriate to give any responsibility for consent to treatment to children below this age. Children of around 14 year-old are normally able to grasp the more subtle and wider aspects of giving consent and the effect that this might have on themselves and other people. But whatever their age and level of maturity, the views of school-age children should always be sought and taken into account when treatment decisions are made.

It is between the ages of eight and sixteen years where difficulties can arise when deciding if a child has sufficient understanding to give consent. The context in which consent to treatment is given or refused is of critical importance. The quality of the relationship between the parent and the child is highly influential, as is the doctorpatient relationship. The majority of young people will normally go along with their parents' wishes and do what they advise, but some children will deliberately do the opposite. Which way this goes will be chiefly influenced by the child's emotional state at the time. Relatives and others who play a significant role in the child's life may also be very influential. Grandparents, teachers, other patients, and non-medical staff sometimes play a crucial role in shaping a child's thinking. Consequently it is essential to try to secure a consensus from all the relevant adults concerned about the proposed treatment before obtaining consent from the child. Unless the child's carers are able to reach a reasonable level of agreement, there is an ethical, moral and possibly legal risk of giving a treatment to which the child alone has consented. This risk recedes as children approach adulthood and independence.

CONTRACEPTION

ADULTS

There is no legal requirement to seek the consent of the spouse/co-habitee. Many practitioners prefer to ask for the consent of both parties before fitting an intra-uterine contraceptive device and, whilst there is no legal requirement to do so, it is sound medical practice.

MINORS

Ordinarily, the proper course for the doctor is first to seek to persuade the girl to bring her parents into consultation, and, if she refuses, not to prescribe contraceptive treatment unless the doctor is satisfied that the patient's circumstances are such that the treatment may proceed without parental knowledge and consent. Lord Scarman acknowledged that a criticism of this view of the law is that it will result in uncertainty and leave the law in the hands of the doctors.

Somewhat more detailed guidance was given in the House of Lords by Lord Fraser of Tullybelton who said that the doctor will be justified in proceeding without the parents' consent or even knowledge provided the doctor is satisfied :

- that the girl will understand the advice;

- that he cannot persuade her to inform her parents or to allow him to infom1 her parents that she is seeking contraceptive advice;

- that she is very likely to begin or to continue having sexual intercourse with or without contraceptive treatment;

- that, unless she receives contraceptive advice or treatment, her physical or mental health, or both, are likely to suffer;

- that her best interests require the doctor to give her contraceptive advice and/or treatment without parental

Lord Fraser commented that this result ought not to be regarded as a licence for doctors to disregard the wishes of parents on the matter whenever they find it convenient to do so.

TREATMENTS OF UNORTHODOX AND CONTROVERSIAL NATURE

According to Section 57 of Mental Health Act (1983) of UK., psychosurgery or surgical implantation of hormones to reduce male sexual drive cannot be done even if the patient consents. A special second medical opinion is also needed as an additional

For similarly unorthodox and controversial therapies in physical medicine, a similar double requirement should be made.

Treatments of such nature should not be given to the following 2 kinds of patients : mentally incompetent adults, or non-consenting patients detained under the Mental Health Ordinance.

JEHOVAH'S WITNESSES AND BLOOD TRANSFUSION

Problems of consent can arise for the doctor faced with a patient, usually a Jehovah's Witness, who refuses to receive blood when, in the doctor's opinion, it is necessary. However, the above principles and the law on consent would be meaningless if the doctor could force blood into an unwilling patient. Competent adults are entitled to refuse treatment.

For the adult Jehovah's Witness a doctor must first decide whether he or she is willing to treat the patient at all in circumstances where a blood transfusion may be necessary. If the doctor is not prepared to allow the patient to die as a result of his or her religious convictions then it might be better not to accept the patient for treatment. If the doctor is willing to undertake treatment then the nature of foe illness and foe need for possible blood transfusion should be explained to foe patient in the presence of a witness who should be warned, in clear terms, of the possible consequences of refusal.

If, despite an unambiguous warning, the patient adheres to his or her refusal to receive blood, he or she should be asked to sign a written declaration of refusal. Alternatively, oral refusal should be recorded by the doctor in the notes and countersigned by the witness.

There is no doubt that many Jehovah's Witnesses appreciate the difficulties for doctors of their religious convictions and a pamphlet was published setting out their position in 1977 which was dist1ibuted to members of the medical profession. This stated that Jehovah's Witnesses are ready and willing to bear responsibility for their refusal to accept blood and to sign legal waivers which relieve medical staff from any concern about legal actions. Similar categrnical assurances were repeated in a 1990 booklet.

For the children of Jehovah's Witnesses, however, the position is not so simple. No signed waiver can protect the doctor from c1iminal proceedings, and it is a criminal offence for anyone over sixteen who has foe custody, charge or care of a child under sixteen willfully to ill-treat, neglect or abandon that child or to expose him to unnecessary suffeiing or injury to health. Should the child die as a result of ill treatment or neglect, foe facts could give 1ise to a charge of manslaughter.

Some years ago it was common practice for the hospital or health aufoority to apply to magistrates for the child to be taken into care when blood transfusion was deemed necessary but parental consent was refused. These care proceedings are seldom needed. Rather it should be for the doctor in charge of the care of the child-patient to do what he or she genuinely believed to be best for the child. These decisions are not easy and should not be left to junior medical staff . Whilst the doctor concerned will hesitate before overriding the wishes of the parents, ultimately a decision will have to be made on the basis that it is the child and not the parent who is the patient.

In reaching a decision the doctor will need to have due regard to all the circumstances relevant to the individual case, and to consider possible alternatives to transfusion of blood or its products. The doctor may also wish to consult with medical and nursing colleagues and perhaps others. If the doctor decides to proceed with a transfusion he or she should of course document the decision, the reasons for it and the fact that one or more colleagues concur.

POST-MORTEM EXAMINATION

There is still some doubt in law as to who - if anyone - is the lawful owner of a dead body. Some have argued that no-one can claim to own a corpse and that, at best, the issue is one of possession rather than ownership. In the case of coroners' post-mortem examinations there is no problem over consent. The coroner's order is a complete

authority to the pathologist to perform the post-mortem examination. In the case of hospital post-mortem examination performed for the purpose of establishing the cause of death or of investigating the existence or nature of abno1mal conditions, the law does require that the authority must be obtained of 'the person lawfully in possession of the body'. It is the health authority or board of governors who are prima facie in lawful possession at the moment of death and remain so until a near relative or executor comes forward to claim the body, and the health authority or board of governors will delegate one or more persons to give authority on their behalf. In the case of a p1ivate institution or a Services hospital the person lawfully in possession would be the managers and commanding officer, respectively.

DEAD DONORS OF ORGAN

The advice of the BMA (1990) on this is as follows:-

(a) If any person, either in writing at any time, or orally in the presence of 2 or more witnesses during his last illness, has expressed a request that his body or any specified part of his body be used after his death for therapeutic purposes or for the purposes of medical education or research, the person in possession of the body after his death may, unless he has reason to believe that the request was subsequently withdrawn, authorise the removal from the body of any part or, as the case may be, the specified part, for use in accordance with the

(b) If the person has not expressed his request as above, the person lawfully in possession of the body can auth01ise the removal of any part of the body for the same purposes as mentioned above if, having made such reasonable enquiry as may be practicable, he has no reason to believe :

1) that the deceased had expressed an objection to his body being so dealt with after his death, and had not withdrawn it; or

2) that the surviving spouse or any surviving relative of the deceased objects to the body being so dealt with.

Where there is any reason to believe that the coroner may require an inquest or a post-mortem examination to be held, authority to remove tissue may not be given nor may tissue be removed without the consent of the coroner.

BODY SEARCH AND BODY SAMPLES FOR POLICE

The Laws on Police and Criminal Evidence contain provision for intimate body searches to be carried out and for intimate samples to be obtained at the request of a senior police officer (superintendent or above) provided that he or she is satisfied that the person concerned is suspected of involvement in a serious arrestable offence and that the sample to be obtained will tend to confirm or disprove such suspicions. However, doctors should be careful in taking such samples if the person does not consent, and they are not required to do so under the Law. Refusal to consent may provide corroboration of evidence subsequently given in court and adverse inferences can be drawn from refusal when there is no good cause for it. Doctors may also be asked to take blood samples under the drinking and driving legislation but should again be careful without the consent of the driver. Penalties are provided for those drivers who unreasonably refuse to provide a sample, and special safeguards are built into the legislation to ensure that the doctor-patient relationship is not compromised.

In cases of doubt, the sample should be taken by a police surgeon with experience in such cases.

SURGICAL IMPLANTS

Any device or prosthesis implanted surgically and intended to remain within a patient's body becomes, in English law, the property of the person in whom it has been implanted. Following a patient's death such implants form part of the estate unless there is specific provision to the contrary.

RADIOISOTOPES

In general, the use of radioisotopes for diagnostic purposes does not come within the definition of a hazardous procedure and employing the minimal radioactivity requires no special consideration concerning the advice and information to be provided to patients. The use of radioisotopes for diagnostic purposes requires that an appropriate explanation be given to patients. The principles involved are the same as for any other radiodiagnostic procedure. It is impo1tant that an adequate note is made of the advice and information provided to the patient. A written consent form is not necessary.

If a radiotherapeutic procedure is to be used which involves the implantation of a radioactive source which could become detached from the patient, and thus present a hazard to the general public, this fact should be clearly explained to the patient and an appropriate entry made in the clinical records. It may be prudent to ask the patient to sign a consent form in respect of such a therapeutic procedure, or when radioisotopes are used for treatment, for example, radio-iodine for thyrotoxicosis.

RESEARCH AND CLINICAL TRIALS

Non-therapeutic procedures, research and trials pose very special problems over consent. The problems are much easier for adults than for minors, the mentally ill or

subnormal. Guidance on research involving patients was published by the Royal College of Physicians of London in January 1990 and includes a section on consent. It is important that patients should know that they are taking part in research. In general, research involving a patient should only be carried out with that patient's consent although there are a few exceptions to this general rule (ibid. section 7.7). Research involving patients should be subject to independent ethical review and it must be made clear to patients that participation in research is entirely voluntary and they may decline to participate without giving a reason, without prejudice to their future care. Patients should also be assured that they may withdraw from research, without the need to give a reason, at any time.

The moral differences between patients and research subjects relate not to respect for autonomy but to two quite different issues. The first is that there is a substantial danger that research subjects will assume that doctors' normal beneficent Hippocratic concern to do their best for their particular patients will also apply to their research subjects. In the case of non-therapeutic research this cannot be the case (by definition), and doctors therefore have a particularly strong moral obligation to make this clear to such subjects. The second, though related, point is that in the normal therapeutic relationship patients can properly assume that any 1isks to which the doctor proposes to subject them will be proposed only in the light of an analysis of risk and benefit that is favourable for the particular patient. Such an assumption would again be quite mistaken in the case of non-therapeutic research (in which the benefits, if any, will accrue to future patients, while the 1isks are taken by the research subjects). Both these points indicate that doctors should make it crystal clear to patients when they are not acting in a therapeutic role.

Research on healthy volunteers poses special problems over consent. The problems are more easily resolved for adults than for minors, the mentally ill or mentally impaired. Guidance on research on healthy volunteers was published by the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1986. There is also advice on medical research involving nonpatient and patient volunteers published in a working party report of the Royal College of Physicians.

ADULTS

A special consent form should be drawn up, with expert advice, tailored to the particular features and requirements of the procedure or research. Very great care is needed in explaining the nature, purpose and effects to the subjects if the practitioner is to avoid accusations of duress, coercion etc. Indeed it may be wise for consent to be obtained by someone wholly independent of the research. The doctors involved with the research may think it wise to tap several sources for advice, including colleagues, ethics committees, research bodies, royal colleges and professional associations. Since the topic is so specialised and individual, further general advice is not likely to be helpful.

MINORS, THE MENTALLY ILL OR SUBNORMAL

Even greater problems are posed for such subjects. Legal opinion is divided about whether or not a parent or guardian can give lawful consent for a non-therapeutic procedure or for research and there are few legal cases on the subject in English law. However, the case of Re D (section lOB) is some authority for the proposition that nontherapeutic procedures on minors may be unlawful if they are irreversible and of no direct benefit to the subject.

OTHER EXECUTIVE DETAILS

IMPLIED OR EXPRESS CONSENT

Legally valid consent may be implied or express. In many consultations and procedures the patient rarely agrees explicitly but will, instead, give implied consent, e.g. the patient will undress and lie on the examination couch when the doctor indicates a wish to conduct an examination; or the patient may roll up a sleeve and offer an arm when the doctor indicates a wish to measure the blood pressure or take a blood sample. Express consent, of course, is given when a patient states agreement in clear terms, orally or in writing, to a request.

ORAL OR WRITTEN CONSENT

A perfectly valid consent may be given orally and there is no absolute need for it to be in writing. However, written consent is sometimes preferable since it provides documentary evidence of the agreement. The problem is a practical one; disputes over consent may arise months or years after the event, by which time memories of an oral consent are unreliable. A witness to an oral consent may be dead or untraceable by the time an allegation of assault is made. Thus, for purely evidential reasons, it is wiser to obtain a signed consent form, duly witnessed.

There is no 'magic', legal or otherwise, in a consent form. It is simply a piece of documentary evidence of the fact that consent was sought and obtained. It is the reality of consent which is important. A consent form signed without knowledge about and/or understanding of the procedure to be performed is valueless.

It would be unrealistic to insist upon a written request for all examinations and procedures and common sense is required in deciding when the consent should be evidenced in writing. As a general rule, a consent form should be completed for any procedure involving a general anaesthetic (which includes most operations) and for many

procedures involving invasive techniques such as endoscopies, biopsies and angiography. It would also be sensible to seek w1itten consent in the case of those whom the practitioner regards as 'difficult' patients.

OBTAINING CONSENT

However consent is obtained, whether express or implied, oral or written, the paramount consideration is that care should be taken to explain the intention, nature and purpose of what is proposed so that the patient truly comprehends that for which his or her agreement is sought. Time so spent is time well spent for the avoidance of future medico-legal complications. In many cases obtaining consent is really too important to be delegated to junior staff or others since it often calls for careful clinical judgment and explanation. For example, junior staff may be unaware of the teclmical details, risks and complications in more specialised surgical procedures, and consent is best obtained by the specialist.

It is necessary to obtain appropriate consent. Consent to 'sterilisation' is not a licence to perform a bilateral salpingectomy, for example, and where two or more procedures are planned it is necessary to have consent for each. Sometimes the procedure which was envisaged is amended and the original description of it is crossed through and the amended procedure added to the consent form without the form being re-signed by the patient. If a change is made to a planned procedure it must be explained to the patient and a new form should be completed, signed and witnessed.

OTHER PROPOSED INNOVATIONS TO HELP MENTALLY INCOMPETENT

ADVANCE DIRECTIVES ABOUT MEDICAL TREATMENT

An advance directive is a statement made by a person when fully competent about the health care that that person would want to receive (under certain circumstances) if he or she were to become incompetent. A "living" will is usually taken to be a special kind of advance directive concerned with refusing life prolonging treatment.

The central argument in favour of advance directives is that they extend patients' control over their health care (Hackler et al, 1989). It is accepted that competent patients have a 1ight to refuse medical treatment and to choose from among the available treatments; advance directives extend such autonomy to incompetent patients who were previously competent. The main argument against advance directives is that competent people are not well placed to make decisions concerning their future incompetent selves. At its most extreme an argument can be made that the incompetent person is, in many of the situations envisaged, quite literally a different person from the person who completed the directive (Dresser, 1989) (Buchanan et al, 1989). The less extreme view is that a fully competent person cannot imaginatively identify with a future incompetent self sufficiently for the advance directive to be relevant.

This doubt is given substance by clinical experience. For example, a woman who many years ago may have made it known that she would not want aggressive life prolonging treatment should she become severely incapacitated may since have suffered several strokes, leaving her aphasic and unable to walk. Yet despite her disabilities and her previous injunction a strong will to live may be obvious.

ENDURING POWER OF ATTORNEY (POA)

It is possible for those who know that they suffer from a disease which will prove mentally incapacitating (eg through the early identification of dementia at a Memory Clinic) to give an enduring POA to a trusted agent, who might be aware, through previous knowledge of the patient, of what their wishes about a particular treatment would be likely to be.

New legislation could be passed to extend the scope of an Endu1ing POA to cover healthmatters but it is likely that only a minority would actually use such a mechanism.

The question that arose in the two cases that went to the High Court was : if a person is already incapable of managing his affairs can he still have the legal capacity to enter into a power of attorney ? In both the cases the master of the Court of Protection found that, although the donors were incapable of managing their own affairs, they were able to understand what an enduring power of attorney was and that the relatives who were given the power were to be their attorneys under an enduring power of attorney. The master referred the question of the validity of the power to the court. Mr. Justice Hoffman ruled that a

. person may validly create an enduring power of attorney even if he is already incapable of managing his property and affairs by reason of mental disorder. It is necessary only that he understands the nature and effect of the power.

GUARDIAN OR ADVOCATE WITH "PARENS PATRIAE" POWERS

The Parens Patriae were the statutory powers under which the Crown used to take responsibility for those who cannot look after their own affairs. The nomination of a responsible guardian, who can give consent to treatment as a responsible parent can for a child, through the endowment of restored "parens patriae" powers to a

guardian appointed by a Guardianship order, could facilitate some of the more difficult treatment decisions.

PANEL OF INFORMED REFEREES

Difficult treatment decisions may be referred to a special panel, which may consist of relatives or f1iends of the patient, lay members, lawyers and independent doctors. This may take the place of the colllis as arbiters of the controversial cases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to express my appreciation to Miss Gloria Wong for preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Applebaum, P. S. & Roth, L. R. (1981) Clinical issues on the assessment of competency. American Journal of Psychiatry, 138: 1462-1465.

Brake!, J. B., Parry, J. & Weiner, B. A. (1986) The mentally disabled and the law. American Bar Foundation, Chicago.

British Medical Association (1990) Rights & responsibilities of doctors. Pages 8-9.

Buchanan, A.E., Brock& D.W. (1989) Deciding for others: the ethics of surrogate decision making. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Collins v. Wilcock (1984) 1WLR 1172; (1984) 3 All ER 374

Department of Health and Welsh Office (1990) A Guide to Consent for Examination or Treatment. London: DoH NHS Management Executive.

Devereux, J. A., Jones, D.P.H. & Dickenson, D.L. (1993) Can children withhold consent to treatment? British Medical Journal, 307: 1459-61.

Drane, J.F. (1985) The many faces of competency. Hastings Center Report, 15: 17-21.

Dresser, R.S. (1989) Advance directives, self-determination, and personal identity. In: Hackler C, Moseley R, Vawter DE, (eds.) Advance directives in medicine. New York: Praeger. Page 155-170.

Eth, S. (1985) Competency and consent to treatment. Journal of American Medical Association;,253: 778-9.

Faden, R R. & Beauchamp, T. L/ (1986) A history and theory of informed consent. Oxford University Press, New York.

Gostin, L (1983) Contemporary social historical perspectives on mental health reform. Journal of Law and Society, 10: 47- 70.

Hackler, C., Moseley, R. & Vawter, D.E. (1989) Introduction: advance directives -- an overview. In: Hackler C, Moseley R, Vawter DE, (eds.) Advance directives in medicine. New York: Praeger. Pagel-8.

Heneghan, C. (1991) Consent to medical treatment. Lancet 337: 421.

Haggett, B. (1984) Mental health law, 2nd edn. Sweet & Maxwell, London.

In re B (1987) 2 All ER 206.

MaCall-Smith, I. (1992) Consent to treatment in childhood. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 67: 1247-1248.

Mackay, R. (1990) Consent to treatment. In Bluglass, R. & Bowden, P. (Eds) Principles & Practice of Forensic Psychiatry. Churchill Livingstone

Maynard v. West Midlands Regional Health Authority (1984) 1 WLR 634; (1985) 1 All ER 635, HL

National Consumer Council of UI{(1990) Patients' Rights. Page 19-22

Odam v. Young (1955) 2 BMJ, 1453.

R v, B; R v. A (1979) 1WLR 1185; (1979) 3 All ER 460.

Re D (1976) 1 All ER 326.

Re F (1989) 2 WLR 1025; (1989) 2 All ER 545.

Re R (1991) (A Minor) (Wardship: Consent to Treatment) 3 WLR 592.

Re W (1992) 4 All ER 627.

Royal College of Physicians of London (1990). Guidelines on the practice of ethics committees in medical research involving human subjects. 2nd ed. London

Royal College of Physicians of London (1990) Research involving patients. London

Royal College of Psychiatrists (1989) Consent of non-volitional patients & de facto detention of informal patients. Council Report CR6: 4.

Scarman Lord (1981) The Scarman report: the Brix.ton disorders 10-12 April 1981. Penguin, Harmondsworth.

Skegg, P. D. G. (1984) Law, ethics and medicine, studies in medical law. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Somerville, M. A. (1980) Consent to medical care. Protection of life series study paper. Law Reform Commission of Canada, Ottawa

Templeman, T. L. & Wollersheim, J. P. (1979) A cognitivebehavioural approach to the treatment of psychopathy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 16:132- 139.

Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania (1977) How

can blood save your life? New York: Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania.

Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania (1990) Jehovah's Witnesses and the Question of Blood. London: Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania.

Whitehouse v. Jordan (1981) 1 WLR 246; (1981) 1 All ER 267, HL

Cheung Hung-Kin MBBS, FRCPsych, FHJ{AM(Psychiatry) Chief of Service, Castle Peak Hospital, Tuen Mun, N. T.,

Hong Kong.