Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2003;13:8-11

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Abstract

Objective: To compare executive function and attention of patients with schizophrenia, their siblings, and healthy controls.

Patients and Methods: The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and Continuous Performance Test were administered to 50 patients with schizophrenia, 50 unaffected siblings of patients with schizophrenia, and 45 healthy controls.

Results: Patients and their siblings performed worse than the healthy controls in the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (p < 0.05). Compared with the healthy controls, patients, but not their siblings, had impaired Continuous Performance Test performance (p < 0.05). Siblings of patients who had significantly higher executive function impairment also tended to have executive function impairment. There was no significant relationship between Wisconsin Card Sorting Test perseverative errors and Continuous Performance Test performance.

Conclusion: The results support not only that patients with schizophrenia have attention and executive function impairments, but also their unaffected siblings have some cognitive function impairments.

Key words: Attention, Cognitive function, Schizophrenia, Siblings

Dr Z Liu, Department of Psychiatry, Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China.

Dr J Zhao, Department of Psychiatry, Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China.

Dr WCC Tam, Department of Psychology, Chung Yuan Christian University, Chung Li, Taiwan.

Address for correspondence: Dr Zhening Liu, Department of Psychiatry, Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410011, China.

E-mail: zheningl@hotmail.com.

Submitted: 6 January 2003; Accepted: 8 September 2003

Introduction

The symptoms of schizophrenia can be divided into 4 dimensions: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, cognitive deficits, and affective symptoms.1 Although cognitive deficits have not yet been included in the diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia, they are one of the important core manifestations of this disorder and provide important diagnostic information, both in the phenotypic and pro- dromal phases. In addition, they may also lead to new clues to the treatment of this disorder.

Genetics is an important aspect in the study of schizo- phrenia. With the use of neuropsychological testing in- struments, the phenotype of the cognitive deficits of patients with this disorder, which is regarded as independent of positive and negative symptoms, may be investigated.2,3 The results of previous studies indicate that the siblings of patients with schizophrenia possess similar cognitive deficits to those manifested in patients with schizophrenia.4-6 However, there has been little research in this area in Chinese people.

In this study, attention and executive function of patients with schizophrenia, their siblings, and healthy controls were investigated. It is hypothesised that both the patients with schizophrenia and their siblings manifest cognitive deficits compared to normal controls.

Patients and Methods

Participants

There were 3 groups of participants, as shown below. All participants were interviewed by 2 psychiatrist investigators who made the diagnoses.

Group 1 comprised 50 patients with schizophrenia recruited from the inpatient and outpatient units of the Department of Psychiatry of the Second Xingya Hospital of Central South University in Changsha, China. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- patients met the diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder described in DSM-IV

- age within 18 to 50 years

- no history of receiving electroconvulsive therapy

- no chronic neurological disorders or severe medical disorders

- no history of alcohol- or substance-abuse

- no colour blindness.

All patients were taking antipsychotic medication, with 22 taking clozapine and 28 taking risperidone. The illness duration of the patients varied from 1 to 375 months (median, 5 months).

Group 2 comprised 50 siblings of patients with schizophrenia, with 1 sibling from each family of 1 patient with schizophrenia. The inclusion criteria were the same as for group 1 except that they were not required to meet the diagnostic criteria of any psychiatric disorders. Each participant and his/her corresponding sibling with schizophrenia had the same biological parents.

Group 3 comprised 45 healthy controls, who were physicians, nurses, or employees from the Second Xingya Hospital. The inclusion criteria were the same as for group 2, with the addition that their first-degree relatives had no history of any psychiatric disorders.

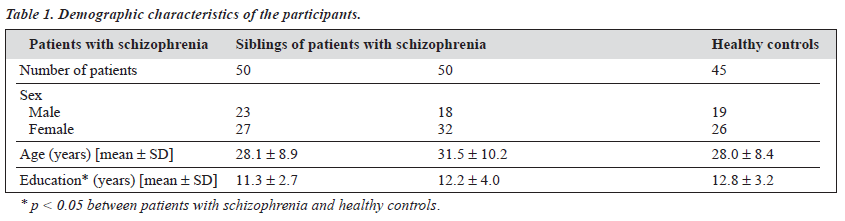

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the 3 groups regarding sex and age (p > 0.05). The educational level of the patients with schizophrenia was significantly lower than that of the healthy controls (p < 0.05).

Methods

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) was used to evaluate the executive function of the participants. The test demanded that the participants discerned through trial and error 3 sorting parameters (colour, number, and shape). Feedback of ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ was provided for each card sorted. After 10 correct sorts, the relevant sorting parameter changed. The test terminated after 5 parameter rules were correctly sorted, or after 128 trials (whichever occurred first).7

A revised version of the Continuous Performance Test (CPT) was used to assess the attention of the participants. The participant was to watch the screen for a specified target digit and press a button when it appeared. Target and distractor digits were presented for 128 milliseconds at the rate of 1 per second. In the first condition, targets and distractors were presented 1 digit at a time. In the second condition, an array of 8 digits was presented, which might or might not contain the target digit. The third condition was the same as the second condition, except that the participant had to respond to a new target digit. There were 11 target digits in each condition.

The data collected were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 10.0. Matched-pair comparisons and correlative analysis were used where appropriate. In addition, analysis of variance (ANCOVA) was used to balance out the effects of the demographic variables.

Results

The correlations between age and educational level with the results of the WCST and CPT are shown in Table 2. The number of perseverative errors of the WCST had significant negative correlation with the educational level of the participants (r = -0.32; p < 0.01). Moreover, the number of correct responses of the CPT had significant negative correlations with age (r = -0.39; p < 0.01) and significant positive correlation with educational level (r = 0.29, p < 0.01). In addition, there was no significant correlation between the results of the WCST and CPT (r = -0.13, p > 0.05).

The results of the WCST and CPT of the 3 groups are shown in Table 3. It was found that education had significant effects on the results of the total trial, perseverative errors, and random errors of WCST (F = 28.96,11.56, 25.74, p < 0.05) and CPT (9.53, p < 0.05). ANCOVA analysis found that for the number of perseverative errors in the WCST, patients with schizophrenia and their siblings had no significant differences, but both groups showed significant differences compared with the healthy controls (p < 0.05). Regarding the number of correct responses of the CPT, the patients with schizophrenia patients showed significant differences compared with their siblings and the healthy controls (p < 0.05), while the latter 2 groups were not significantly different. For the number of total trials and random errors of WCST, each group showed significant differences (p < 0.05). It was found that medication had no

significant effects on the results of total trials, correct responses, perseverative errors, random errors, and categories completed of the WCST (F = 0.07, 0.18, 0.01, 0.04, 0.24, p > 0.05) and CPT (F = 0.08, p > 0.05). Similarly, it was found that sex and age had no significant effects on the results of both WCST (p > 0.05) and CPT (p > 0.05).

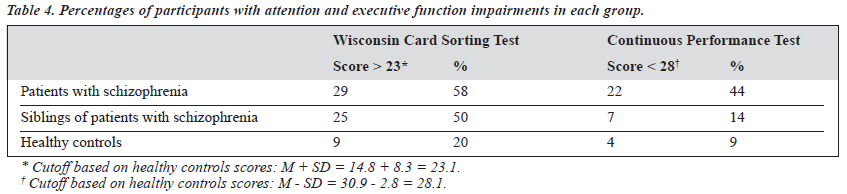

Participants with perseverative errors of the WCST 1 standard deviation above the mean number of the healthy control group (14.8 + 8.3 = 23.1) are regarded to have executive function impairments. In this study, 58% of the patients with schizophrenia (29 participants), 50% of their siblings (25 participants), and 20% of healthy controls (9 participants) showed executive function impairments. Of the 29 patients with schizophrenia with this impairment, 19 of their siblings also had the same impairment (66% of the 29 patients with schizophrenia). On the other hand, of the 21 patients with schizophrenia with no executive function impairments, 6 of their siblings (29% of the 21 patients with schizophrenia) had this impairment. There was a significant difference (c2 = 6.65, p < 0.01) between the percentages of the siblings with executive function impairments and the patients with schizophrenia having the same impairments and the siblings with the impairments from patients with schizophrenia without this impairment. In addition, participants with correct responses of the CPT 1 standard deviation below the mean number of the healthy control group (30.9-2.8 = 28.1) were regarded to have attention deficit. In this study, 44% of the patients with schizophrenia (22 participants), 14% of their siblings (7 participants), and 9% of the healthy controls (4 participants) showed attention deficits. Of the 22 patients with schizophrenia with this impairment, 2 of their siblings also had the same impairment (9% of the 22 patients with schizophrenia). On the other hand, of the 28 patients with schizophrenia with no attention deficits, 5 of their siblings (18% of the 28 patients with schizophrenia) had this impairment. There was no significant difference (c2 = 0.23, p > .05) between the percentages of the siblings with attention deficits from patients with schizophrenia with the same impairment and the siblings with the impairments from patients with schizophrenia with- out this impairment. These results were shown in Table 4.

Discussion

In this study, cognitive functions of patients with schizophrenia and their siblings were investigated using neuropsychological assessment instruments. There were 3 major findings. First, attention and executive function of the patients with schizophrenia were significantly worse than that of the healthy controls, which was compatible with the results of many previous studies.4,5,8-10 In addition, the executive function of the siblings of the patients with schizophrenia was also significantly worse than that of the healthy controls. Second, the proportion of patients with schizophrenia with attention and executive function impairments were significantly higher than those of the healthy controls. The proportion of the siblings of patients with schizophrenia with executive function impairments was also significantly higher than that of the healthy controls. In addition, based on the 2 groups of patients with schizophrenia — with or without executive function impairments — the proportion of siblings from the former

group was significantly higher than the proportion of siblings from the latter group in having the same impairment. This implies the possibility of the heritability of executive function impairments, which might be used in the classification of schizophrenia subtypes. Third, since there was no significant correlation between attention and executive function, the executive function impairments of both the patients with schizophrenia and their siblings might not be due to attention problems.

Research shows that the WCST assesses the cognitive functions of the frontal lobe, including abstraction, concept formation, selective memory, and flexibility, and the number of perseverative errors is a useful index of the frontal lobe function.11 The CPT assesses attention, which includes conditions with or without interference. The results of the study by Egan et al indicated that compared with normal controls, patients with schizophrenia had attention deficits, and the proportion of siblings having attention deficits from affected schizophrenic patients was high.9 Chen et al obtained similar results,8 except that the proportion of first- degree relatives (including parents) with attention deficits was higher than that of Egan et al.9

Using WCST, Egan et al showed that the proportions of patients with schizophrenia and their siblings with executive function impairments were significantly higher than those of the healthy controls.9 Moreover, the proportion of affected siblings of patients with schizophrenia with the same impairment was the highest. The results of this study were compatible with that of Egan et al.9 However, the proportion of siblings with attention deficits from patients with schizophrenia with the same deficit was not the highest in this study.

In addition, the attention of the male participants was significantly better than that of the female participants. Age and educational level also had significant effects on attention. That is, the attention of older participants was worse than that of the younger participants, while the attention of the participants with higher educational level was better than that of those with lower educational level. These are similar to the results of the study by Chen et al.8 On the other hand, executive function measured by the number of perseverative errors of the WCST seemed to be affected by educational level but was independent of sex and age. In other words, participants with a higher educational level showed better executive function performance.

In conclusion, the results of this study support the herita- bility of the cognitive deficits of patients with schizophrenia, and these deficits may exist in relatives without the diagnosis of this disorder. Further research may increase the sample size, perform risk evaluation, or conduct genetic analysis, with the goal of identifying the possible affected genes.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr Eric YH Chen for his comments on the manuscript.

References

- Yager J, Gitlin MJ. Clinical manifestation of psychiatric In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehen- sive textbook of psychiatry. 7th ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:789-823.

- Nieuwenstein MR, Aleman A, de Haan, EHF. Relationship between symptom dimensions and neurocognitive functioning in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of WCST and CPT studies. J Psychiat Res 2001;35:119-125.

- Schatz J. Cognitive processing efficiency in schizophrenia: generalized vs domain specific deficits. Schizophr Res 1998;30:41-49.

- Finkelstein JRJ, Cannon TD, Gur RE, Gur RC, Moberg P. Attentional dysfunctions in neuroleptic-naive and neuroleptic-withdrawn schizo- phrenic patients and their siblings. J Abnorm Psychol 1997;106: 203-212.

- Keri S, Kelemen O, Benedek G, Janka Z. Different trait markers for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a neurocognitive approach. Psychol Med 2001;31:915-922.

- Waldo MC, Freedman R. Neurobiological abnormalities in the relatives of schizophrenics. J Psychiat Res 1999;33:491-495.

- Heaton RK. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1981:39-52.

- Chen WJ, Hsiao CK, Hsiao LL, Hwu HG. Performance of the Continuous Performance Test among community samples. Schizophrenia Bull 1998; 24:163-174.

- Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Gscheidle T, et al. Relative risk of attention deficits in siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1309-1316.

- Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Gscheidle T, et al. Relative risk for cognitive impairments in siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2001;50:98-107.

- Liu Z. The clinical usage of Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Foreign Medical Sciences 1999;26:6-9.