Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2003;13(4):6-13

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

A Malhotra, D Basu, SK Mattoo, N Gupta, R Malhotra

Abstract

Objective: Naltrexone is reported to be a reasonably effective treatment for relapse prevention for patients with opioid dependence. However, there is a lack of data on outcome and acceptability for Indian patients.

Patients and Methods: A prospective, longitudinal, open-label, intent-to-treat study was performed in which 106 patients with opioid dependence were given naltrexone 50 mg daily for 6 months.

Results: Fifty eight patients (55%) were followed up and reassessed after 6 months. The follow- up and drop-out groups were comparable. Using last outcome carried forward analysis, the overall abstinence rate was 52% (55 of 106 patients). Side effects were uncommon, mild, and transient, with bitter taste being the commonest, and there was no hepatic dysfunction. Level of satisfaction and perception regarding naltrexone as treatment for opioid dependence was reported to be satisfactory and reasonably high by the patients and their attendants/relatives, respectively.

Conclusion: Naltrexone appears to be an acceptable treatment for opioid-dependent patients in India. However, controlled and randomised trials are warranted to evaluate associated factors.

Key words: Acceptability, Naltrexone, Opioid dependence, Outcome

Dr A Malhotra, DM & SP, PhD, Additional Professor, Drug De-Addiction and Treatment Centre, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Dr D Basu, MD, DNBE, MAMS, Associate Professor, Drug De-Addiction and Treatment Centre, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Dr SK Mattoo, MD, Additional Professor, Drug De-Addiction and Treatment Centre, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Dr N Gupta, MD, Assistant Professor, Drug De-Addiction and Treatment Centre, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Mr R Malhotra, MA, Social Scientist, Drug De-Addiction and Treatment Centre, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Address for correspondence: Dr A Malhotra, Additional Professor of Clinical Psychology, Drug De-addiction and Treatment Centre, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh-160 012, India.

Tel: (0172) 274 7585, ext 6220

Fax: (0172) 744 401

E-mail: ddtc1@sify.com

Submitted: 5 April 2002; Accepted: 28 December 2003

Introduction

Opioid dependence is a significant medical and social problem, with such patients being at significant risk for developing human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis.1 A promising treatment for relapse prevention in patients with opioid dependence is naltrexone. Naltrexone is a long-acting competitive opioid antagonist that blocks the reinforcing effects of opioids and eliminates opioid self-administration.2 It is reported to be well tolerated with few or no agonist effects at therapeutic doses.1

Numerous open-label, placebo-controlled, and double- blind trials of naltrexone have been performed.1,3,4 However, due to variable sample sizes and outcome parameters, the results obtained have been ambiguous in terms of the clinical effectiveness of naltrexone for relapse prevention.2,3 The major limitations associated with naltrexone are low retention rates, with most patients stopping treatment within 2 months,4 and absence of studies assessing outcome and compliance at or beyond 6 months.

Many studies are available from the West assessing the efficacy and retention rates with naltrexone. Outcomes have been fair to good with retention rates ranging from 0% to 50%.4 A recent study from China reported abstinence rates of approximately 25% using both double-blind and open- label methodologies.5 However, there is only 1 study from India evaluating the efficacy of 3 months of naltrexone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence.6 This is intriguing, bearing in mind the high prevalence (and associated complications) of opioid dependence in India where methadone maintenance therapy for opioid depen- dence is not available. Also, use of buprenorphine sublingual tablets is not regular, the cost is reasonably high, and efficacy studies are lacking.

Naltrexone, on the other hand, has been available in India for at least 5 years. Although, the high price during the initial years precluded its use by clinicians and patients alike, the cost has substantially reduced in the past 24 months. In India, naltrexone is frequently used as a relapse prevention strategy for opioid dependence. However, the efficacy, outcome, and retention rates are unknown, highlighting the importance of developing a database of the efficacy and acceptability of naltrexone therapy in India.

With these issues in mind, this study, with an open- label, naturalistic treatment design, was planned to broadly assess the acceptability of naltrexone for opioid-dependent patients in India. The following are the objectives of the study:

- to characterise the acceptance of naltrexone for relapse prevention of patients with opioid dependence

- to compare the follow-up and drop-out groups

- to evaluate the acceptability and tolerability of naltrexone during a 6-month period.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The study group comprised patients attending the Drug De- addiction and Treatment Centre (DDTC), Department of Psychiatry at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh, India, with a primary International Classification of Diseases-10 diagnosis of opioid dependence syndrome.7 Patients were recruited from both outpatient and inpatient facilities of the DDTC between August 1999 and December 2000.

All patients who were cooperative and expressed a willingness to participate in the study were recruited. The presence of hepatic dysfunction and major physical ill- ness served as exclusion criteria. However, patients with comorbid substance abuse and psychiatric illnesses were included as this study aimed at assessing the acceptability of naltrexone for patients with opioid dependence seeking treatment from a specialty service.

Setting

The DDTC is a specialist centre for treating addiction-related problems and disorders. It is located in a tertiary care referral hospital setting in North India with a catchment area catering to approximately 40 million people. The DDTC provides both outpatient and inpatient services with the focus on both detoxification and relapse prevention management strategies. The treatment model is based on an integrated biopsycho- social approach to addiction.

Instruments

The following instruments were administered to the patients and their relatives.

- The Sociodemographic Profile Sheet was developed by the Department of Psychiatry. The instrument comprises variables such as age, sex, education, occupation, marital status, and locality.

- The Clinical Profile Sheet was developed by the investigators for the purpose of this study. The sheet comprises variables such as the nature of the substance used, duration of dependence, relapse-related history, comorbidity, and side effects.

- The Attitudes and Perception Scale for Naltrexone (APSN) is a 10-item scale developed by the investigators, and aimed at assessing the attitude to and perception about naltrexone. Each item is scored from 0 to 2, with a maximum possible score of 20. A higher score indicates better attitude to and perception about naltre

- The Multiphasic Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) is derived from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory.8 The questionnaire was developed and validated in 9 It is a 100-item forced choice true/ false inventory that evaluates the personality profile for anxiety, depression, mania, paranoia, schizophrenia, hysteria, psychopathic deviation and lie scale, and repressor-sensitiser scales.

- The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was developed for this study. The scale is a linear scale, ranging from 0 to 10, for assessing the overall level of satisfaction with the treatment methods.

Procedure

All patients underwent detoxification for the management of their withdrawal symptoms. The detoxification process was carried out using clonidine, analgesics, and nitrazepam for a period of 10 to 14 days. All patients had to be opioid free (as reported by self, family, or staff report and presence of negative urinary thin layer chromatography [urine TLC]) for at least 7 days prior to initiation of therapy.

During recruitment, baseline assessment was carried out. The patients and their attendants or relatives were counselled about the need for naltrexone and a brief summary was provided about the mechanism of action and cost. Thereafter, patients were administered the instruments in order, while the attendants or relatives were administered instruments 3 and 5. Baseline liver function tests (LFT) were also obtained and naltrexone 50 mg/day was initiated for a period of at least 6 months.

Follow-up was arranged in the first 3 to 4 weeks, although flexibility was ensured for individual patients. During the follow-up, an independent clinician enquired as to the patients’ status and the exact clinical status was recorded in the file. Attempts were made by the investigators to counsel the patients and attendants during these visits.

Additionally, to ensure the authenticity of the information provided in relation to abstinence or naltrexone use, urine- screening assays (urine TLC) were requisitioned. Although urine toxicology is the most common and preferred method for opioid detection, it is limited by the fact that it only determines the absolute amount of drug present in the urine — excretion and concentration of a drug in urine is affected by several factors such as the dilution and acidity of the urine — and the form in which the drug was originally taken or when and how much was taken cannot be determined from a positive urine test.10 However, amongst the various urine toxicology methods, TLC is the least expensive and is reliable.10

Subsequently, patients were re-assessed after completion of the 6-month period following initiation of naltrexone. Patients were administered instruments 1 to 5 and attendants and relatives were administered instruments 3 and 5.

Definitions used in the study include the following:

- drug-free period — the time elapsed between the first day of naltrexone administration and the first evidence of opiate use (either by positive urine test for opiate or the day on which the patient reported opiate use)3

- relapse — routine use of opiates since detoxification lasting for at least 2 weeks of daily use4

- non-relapse/lapse — no return to a period of routine opiate use, but may have had occasional episodes of opiate use.4

Statistical Analysis

Discrete (categorical) variables were analysed using Chi- square of Fisher’s Exact Probability Test. Continuous variables were analysed using Students’ t-test and paired t-test (for repeat measures). To compare time until the patient was compliant with naltrexone versus those non- compliant with naltrexone, a survival curve was plotted for the follow-up group. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 7 for Windows.

Results

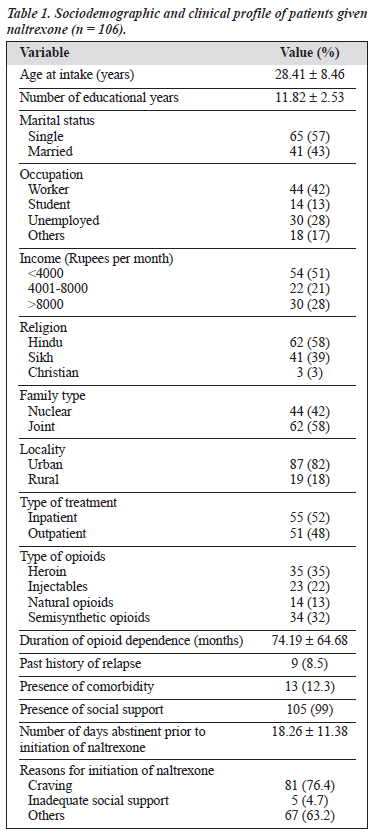

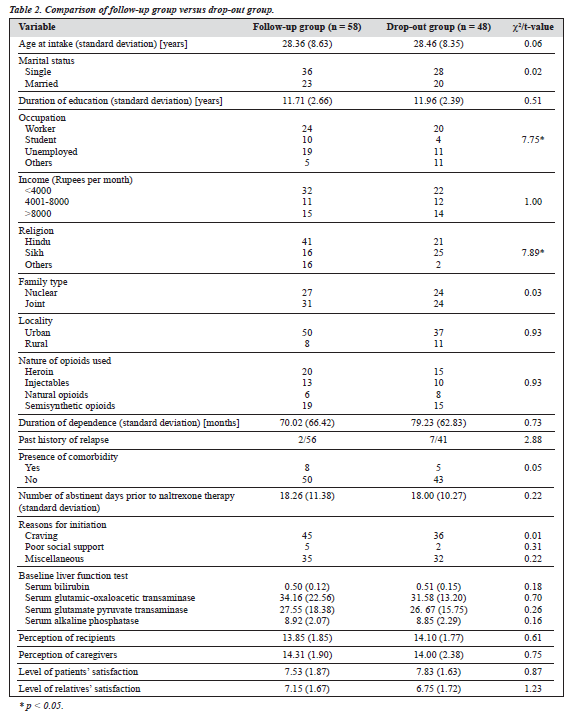

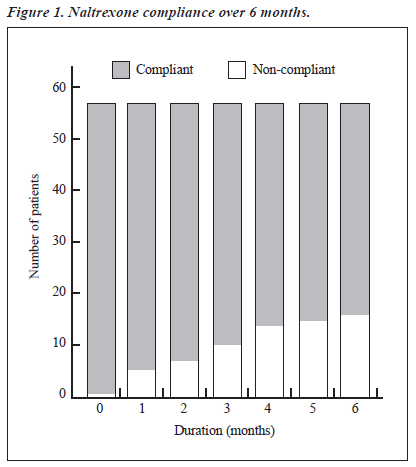

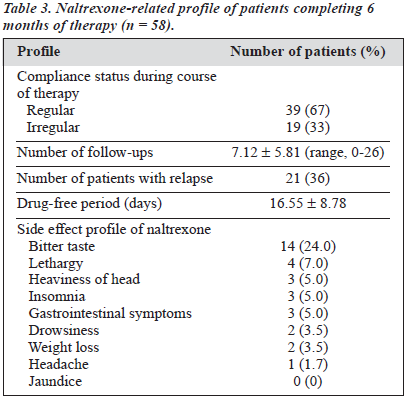

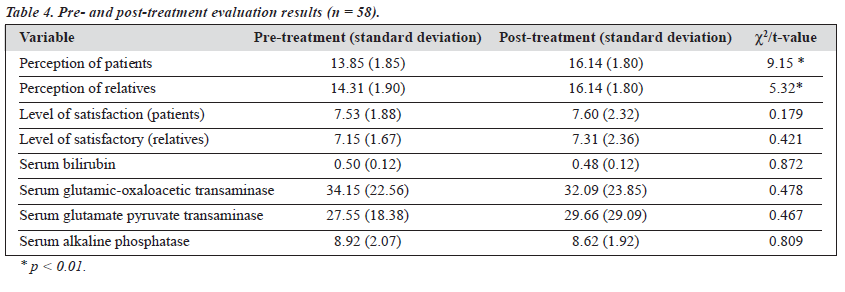

The study group comprised 106 males with various types of opioid dependence seeking treatment from a tertiary care specialty clinic. The characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1. All 106 patients were given naltrexone and followed up for 6 months. At the end of the 6-month period, only 58 patients (55%) were re-assessed; the remaining 48 (45%) had dropped out or were untraceable. Various socio-clinical variables of the 2 groups were compared (Table 2). Both groups were nearly comparable on all the socio-clinical variables. A survival curve was charted for the ‘follow-up’ group in relation to compliance status when taking naltrexone (Figure 1). The follow-up group of 58 patients was then subject to further analysis to assess therapy-related parameters (Table 3). Additionally, to evaluate the acceptability of naltrexone as a mode of relapse prevention for opioid dependence, a pre- and post-treatment comparison was carried out (Table 4).

Overall analysis of patients taking naltrexone therapy showed that, of the 58 patients completing the protocol of assessment, 32 (55%) were abstinent and 26 (45%) had relapsed. Intent-to-treat analysis was performed for the drop-out group. The last outcome was carried forward, taking this as equivalent to the possible outcome measure at 6 months, thereby generating outcome data for this group. Of the 48 patients not completing the protocol of assessment, 23 (48%) were deemed abstinent and 25 (52%) relapsed. Hence, the cumulative outcome status was 55 patients (52%) being abstinent and 51 (48%) having relapsed at re-assessment 6 months after the start of naltrexone therapy.

Discussion

This prospective follow-up study attempts to characterise patients with opioid dependence (with or without other substance dependence) taking naltrexone therapy. The study participants were all men of a relatively young age and educated for approximately 10 years. Predominance of single persons of low socio-economic status, Hindu, unmarried, urban men were seen. The socio-demographic profile of these patients was similar to that of the population attending the DDTC during 1999.11 Regarding the type of opioids,

there were fewer patients using heroin compared with the DDTC population, the reasons for which are unclear. Patients had a mean duration of at least 6 years of dependence with psychosocial complications in various areas. However, 90% had never sought treatment for their drug dependence. Comorbidity was reportedly higher than that seen in the DDTC clinic population, and could be attributable to the selection procedure. An important aspect was the presence

of social support for nearly all patients; this finding is contrary to patients taking naltrexone in the West.4

Despite a minimum 10- to 14-day detoxification period, patients were opioid-free for a mean of 18 days, thereby ensuring absence of any withdrawal symptoms precipitated by use of naltrexone. Amongst the reasons for initiation of naltrexone, craving was predominant. Various other factors included presence of comorbidity, past history of relapse, and ability to afford naltrexone. Although social support was available for 99% of patients, 5% had inadequate support (from a clinical impression) as a reason for naltrexone therapy.

At the end of the 6-month study period, only 58 patients (55%) could be contacted and re-assessed. Hence, the retention rate was 55%, which is reasonably high compared with studies from the West4 and the study from China.5 Previous open-label trials of 6 months duration have generally reported retention rates ranging from 5%12 to 80%.13 Reasons given for the high retention rates were that patients were highly motivated to succeed due to being health care professionals,14,15 having their employment in jeopardy, or were stopping opioid use as the result of legal programs.13 Other reasons include the presence of supplementary family therapy,12 counselling for relapse prevention,4 and contin- gency management.1

Our study shows a reasonably high overall retention rate bearing in mind that no specific psychosocial interventions were supplemented to naltrexone therapy apart from specific pre-treatment counselling. In fact, most studies from the West included supplementary psychological interventions.4

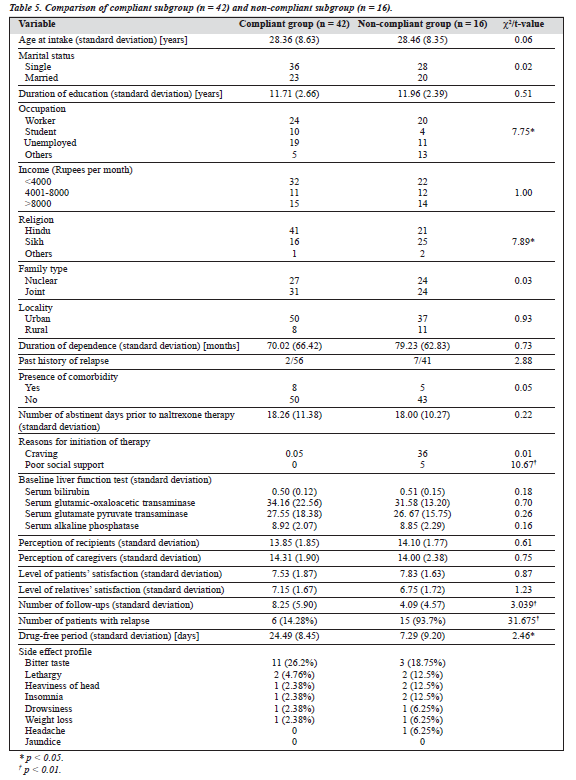

Of the total number of patients, 58 (55%) were reassessed at 6 months. Figure 1 shows the compliance status on a monthly basis. As can be seen, regular compliance was maintained by 83% at 3 months, 76% at 5 months, and 72% at 6 months. In contrast, the study by Rabinowitz et al reported that at least 50% of non-relapse patients continued naltrexone therapy at 5 months, which declined to 20% by the end of 9 months.4 Hence, the results obtained for regular compliance with naltrexone over a period of 6 months were better in this study. On comparing the compliant subgroup (n = 42) with the non-compliant subgroup (n = 16), it was noted that the patients in the compliant subgroup were more likely to be unmarried, with poor social support, without

lapses during therapy, and experienced fewer side effects than the non-compliant subgroup. Also, the compliant subgroup had more follow-up visits and drug-free periods than the non-compliant subgroup (Table 5). Although the study design did not permit a proper and detailed evaluation of the factors associated with compliance status, considera- tion may be given to the following speculative factors:

- the study by Rabinowitz et al evaluated patients who had undergone a different detoxification therapy;4 the type of detoxification has been shown to have a bearing on compliance to naltrexone2

- compliant patients in our study had good social support, which was not commented upon in the other study

- compliant patients probably experienced a lesser degree of side effects and cravings.

In the only Indian study, Shah et al reported a 24% retention rate at the end of a 3-month period despite a reduction in craving and lack of side effects.6 Hence, reasonably heartening results relating to overall compliance in patients completing the 6-month protocol are seen in this study.

An intent-to-treat analysis was planned, in which the last outcome was carried forward (LOCF) for the attrition group as the follow-up and attrition (drop-out) groups were comparable. Hence, outcome status for the whole group (n = 106) was 52% abstinent and 48% relapsed. This figure of 52% for abstinent patients at 6 months was higher than the 32% abstinence reported by Greenstein et al16 and that of 23% to 31% reported by Guo et al5 but less than the rates at 1-year follow-up reported by other authors.13,15,17 The higher rates in these studies are probably attributed to having more motivated groups of patients.

The second objective of the study was to compare the follow-up (n = 58) and drop-out (n = 48) groups. Both groups were comparable except for over-representation of students/ unemployed persons and Hindus in the follow-up group. It could be speculated that the lack of a regular occupation was a strong motivating factor for ensuring follow-up. However, the difference in religion is difficult to explain. Importantly, the presence of previous relapse, comorbidity, type of opioids, duration of dependence, and presence of craving did not lead to any significant differences in the 2 groups. The baseline LFT was also comparable, eliminating the possibility of pre-evaluation hepatic dysfunction contributing to dropping out. Assessment of personality profile (based on the MPQ) also revealed comparable psychopathology across all the scales, ruling out the role of personality in contributing to the drop-out rate. To evaluate whether the treatment parameters were contributing to the drop-out rate, level of satisfaction of patients (in relation to management already carried out, i.e. detoxification) was evaluated and found to be comparable. Additionally, the perception of patients (after counselling) regarding naltrexone was comparable. In India, the family has an important role to play in the management.18 Since adequate social support was available for nearly all the patients, the level of satisfaction and perceptions of the key caregivers (attendants or relatives) was also assessed. Both groups were comparable for these parameters.

Hence, it may be concluded that socio-clinical profile, personality traits, and treatment perception and satisfaction could not explain drop-out status. It is possible that a com- plex interplay of individual, social, and cultural factors could be determining poor compliance. A similar finding has been reported in other studies,4,19 in which unmarried status (with associated lack of stable relationships) and longer naltrexone use was associated with a higher relapse rate.

The third and final objective was to assess the tolerability and acceptability of naltrexone, Regarding the tolerability of naltrexone, the emergence of side effects during therapy and baseline and final LFT scores was evaluated. The commonest side effect reported was bitter taste (24%), followed by occasional nausea, headache, lethargy, and gastrointestinal upset. All the side effects were mild and transient, similar to other studies.1,3-6 None of these side effects led to any modification in the naltrexone regimen. The duration of the drug-free period was 16.55 ± 8.78 days for 21 patients (36%) who reported opioid use during naltrexone therapy. Such a high rate of opioid use during naltrexone therapy could be due to the lack of euphorogenic effects of naltrexone during periods of abstinence2 or the presence of cravings leading to experimentation with opioids during naltrexone therapy. Additionally, this experimentation was seen during the initial 2 to 3 weeks of the start of naltrexone therapy, lending credence to the possibility of the latter hypothesis.

The patients and their caregivers had reported a reasonably high level of satisfaction with the detoxification treatment (or treatment carried out prior to initiation of naltrexone). Even after completion of 6 months of therapy, this level of satisfaction was maintained (Table 4), reflecting that naltrexone was found to be a satisfactory, if not effective, mode of therapy for patients with opioid dependence. The heartening feature to highlight is that the patients continued to maintain a reasonable degree of confidence and satis- faction with the treatment team and treatment strategies. This could possibly be due to the known fact that more intensive input and frequent therapeutic contact improves compliance (and motivation) for these patients.1,4 The second factor assessed for acceptability of naltrexone was the perception of patients and their caregivers regarding the drug. Both groups showed a significant and positive difference in perception relating to naltrexone (Table 4). One may extrapolate that this significant positive change indicates a positive attitude, better acceptability, and higher degree of confidence towards naltrexone for relapse prevention; however, the exact reasons cannot be ascertained. Overall, in relation to tolerability and acceptability of naltrexone, favourable results were obtained. This high degree of satisfaction and positive attitude is additionally heartening bearing in mind the high cost of naltrexone therapy (approximately Rupees 40/day; Rupees 1200/month; and Rupees 7200 for 6 months). Hence, it can be seen that family members and/or patients were willing to bear the high cost of treatment and were not disappointed with the results obtained with naltrexone. Possibly, the model of ‘harm minimisation’ with the use of naltrexone may have operated even for the relapsed patients.

To summarise, naltrexone use for relapse prevention in opioid dependence over a 6-month period is associated with a moderate retention rate (55%) and abstinence (52%). However, no variables could predict whether a patient would stay in treatment or drop out of therapy. The retention rate and compliance to naltrexone of patients receiving therapy showed a steady decline over the study period. However, side effects were mild, transient, and uncommon (except for bitter taste). No hepatic dysfunction was observed. A positive and better attitude towards naltrexone with a high degree of acceptability and satisfaction for the treatment provided was seen. However, these results should be interpreted in light of certain limitations, including lack of a comparison group, probable selection bias in taking better motivated patients, lack of structured assessment for outcome status at periodic (monthly) intervals, a reasonably high drop-out rate, and possible role of other psychosocial interventions in contributing to the favourable results.

It can be concluded that, unlike in the West,1 naltrexone is an acceptable, safe, and reasonably effective mode of relapse prevention therapy for patients with opioid de- pendence in the Indian setting. There is a need for controlled trials on this aspect. The high cost of naltrexone is a factor operating against its regular use by clinicians and easy acceptability by patients. Hence, there is a need to evaluate further the factors affecting the acceptability of naltrexone in this setting.

References

- Preston KL, Silverman K, Umbricht A, Dejesus A, Montoya ID, Schuster CR. Improvement in naltrexone treatment compliance with contingency management. Drug Alcohol Depend 1999;54:127-135.

- Gonzalez JP, Brogden RN. Naltrexone: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in the management of opioid dependence. Drugs 1988;35:192-213.

- Shufman EM, Parat S, Witztum E, Gandacu D, Hamburger RB, Ginath Y. The efficacy of naltrexone in preventing reabuse of heroin after detoxification. Biol Psychiatry 1994;35:935-943.

- Rabinowitz J, Cohen H, Tarrasch R, Kotler M. Compliance to naltrexone treatment after ultra-rapid opiate detoxification: an open label naturalistic study. Drug Alcohol Depend 1997;47:77-86.

- Guo S, Jiang W, Wu Y. Efficacy of naltrexone hydrochloride for preventing relapse among opioid-dependent patients after detoxification. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2001;11(4):2-8.

- Shah LP, Patil JV, Hanumata K, et al. An open clinical trial of naltrexone in patients suffering from opioid dependence. Indian J Psychiatry 1995;37(Suppl):25.

- World Health Organization. ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

- Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1955.

- Murthy HN. Multiphasic Personality Questionnaire. Bangalore: Trans AIIMH; 1970.

- Kapur BM. Drug-testing methods and clinical interpretations of test results. Bull Narc 1983;XLV(2):115-154.

- Department of Psychiatry. Annual patient statistics. Chandigarh: Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research; 1999.

- Anton RF, Hogan I, Jalali B. Multiple family therapy and naltrexone in the treatment of opiate dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 1981;8: 157-168.

- Gold MS, Dackis CA, Washton AM. The sequential use of clonidine and naltrexone in the treatment of opiate addicts. Adv Alcohol Sub Abuse 1984;3:19-39.

- Ling W, Wesson DR. Naltrexone treatment for addicted health-care professionals: a collaborative private practice experience. J Clin Psychiatry 1984;45:46-48.

- Washton AM, Gold MS, Pottash AC. Successful use of naltrexone in addicted physicians and business executives. Adv Alcohol Sub Abuse 1984;4:89-96.

- Greenstein RA, Arndt IC, McLellan T, O’Brein CP, Evans B. Nal- trexone: a clinical perspective. J Clin Psychiatry 1984;45:25-28.

- Judson BA, Goldstein A. Naltrexone treatment of heroin addiction: one year follow-up. Drug Alcohol Depend 1984;13:357-365.

- Lobana A, Mattoo SK, Basu D, Gupta N. Quality of life in schizophrenia in India: comparison of three approaches. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;104:51-55.

- Lewis DC, Mayer J, Hersch RG, Black R. Narcotic antagonist treat- ment: Clinical experience with naltrexone. Int J Addictions 1978;13: 961-973.