East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018;28:9-16

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Sinha Preeti, MD, Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India.

Dr Shetty Disha Jayaram, MD, Department of Pharmacology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka, India.

Dr Andrade Chittaranjan, MD, Department of Psychopharmacology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India.

Address for correspondence: Dr Sinha Preeti, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Hosur Road, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India-560029. Tel: (91) 8026995273 / 9243328988; Email: drpreetisinha@gmail.com

Submitted: 20 February 2017; Accepted: 14 August 2017

Abstract

Objective: To investigate early evolution, tolerability, and predictors of antidepressant-emergent sexual dysfunction in patients with anxiety or depressive disorder.

Methods: Patients with anxiety or depressive disorders who were prescribed antidepressant monotherapy (mirtazapine, sertraline, desvenlafaxine, escitalopram, or fluoxetine) at the discretion of the treating clinician were recruited from July 2012 to June 2014 from a hospital outpatient service. All were free of psychotropic medication for least 1 month. Sexual function was assessed at baseline, week 2, and week 6 using the Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction Questionnaire (PRSexDQ). A PRSexDQ score of ≥ 2 was considered to indicate sexual dysfunction. Sexual function was dichotomised to ‘favourable’ or ‘impaired’.

Results: Of 230 patients recruited, 209 were assessed at baseline of whom 184 were assessed at week 2; of these, 154 were also assessed at week 6. At baseline, 138 (66%) of the 209 patients were diagnosed with depressive disorder and 71 (34%) with anxiety disorder; 29% of patients had sexual dysfunction (in any domain of PRSexDQ). By week 6, the percentage had increased to 41%, although the change in the mean PRSexDQ score was only marginal (from 1.04 at baseline to 1.55 at week 6). With regard to individual questionnaire items, by week 6, sexual desire improved, but erectile and ejaculatory function in men and orgasmic function in women worsened. Fluoxetine and sertraline were associated with impaired sexual function, whereas mirtazapine was associated with favourable sexual function. In a logistic regression analysis, at week 2, mirtazapine and desvenlafaxine were predictors of favourable sexual outcome, whereas fluoxetine and higher baseline PRSexDQ score were predictors of impaired sexual outcome. At week 6, mirtazapine remained a predictor of favourable sexual outcome, whereas fluoxetine, higher 2-week PRSexDQ score, and adequate dose were predictors of impaired sexual outcome.

Conclusions: In patients with anxiety or depressive disorder, the risk of antidepressant-emergent sexual dysfunction at 6 weeks is low when drug doses are initially low with gradual up-titration. Baseline sexual dysfunction was independently associated with impaired sexual outcome. Men may be more likely than women to experience impaired sexual outcome. In patients with baseline sexual dysfunction, prescription of mirtazapine might be preferable to fluoxetine.

Key words: Anxiety; Depressive disorder; Sexual dysfunctions, psychological

Introduction

Sexual dysfunction is common in patients with psychiatric disorders.1 Its prevalence can be increased by psychotropic drugs.2-4 Sexual adverse effects of antidepressants are distressing and can compromise adherence to treatment.2,5 Meta-analyses of antidepressant-emergent sexual dysfunction have identified bupropion and nefazodone, and possibly mirtazapine, to be associated with a lower risk of sexual symptoms.6-9 Nonetheless, the risk of various selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors is not well known; some meta-analyses have reported that certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have higher rates of sexual adverse effects,6,8 whereas one study reported that fluvoxamine is nearly as benign as bupropion.7

Many studies have been limited by a variety of factors including a lack of baseline evaluation of sexual function, cross-sectional nature, comparison of 2 or 3 antidepressants only, and use of inappropriate instruments to determine sexual function.2,8,10 In addition, patient tolerance of sexual adverse effects, despite playing a key role in treatment adherence, has been rarely reported. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study using multivariable analysis to determine the predictors of antidepressant-emergent sexual dysfunction. This study aimed to investigate early evolution, tolerability, and predictors of antidepressantemergent sexual dysfunction in patients with anxiety or depressive disorder.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Kasturba Hospital, Manipal, Karnataka, India. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Patients with anxiety or depressive disorder were recruited by convenience sampling from the adult outpatient service of the Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Hospital from July 2012 to June 2014. All were free of psychotropic drug treatment for least 1 month before recruitment. None was pregnant or postpartum, or had any significant neurological or psychiatric comorbidity.

Assessments were conducted at baseline and after 2 weeks (± 2 days) and 6 weeks (± 4 days) by a physician who was blinded to the diagnosis and treatment. Before the follow-up visits, a reminder telephone call was made. Patients who missed their follow-up visits were again contacted by telephone. Patients were instructed to return for assessment if there was any treatment-emergent adverse event; they were offered the option of continuing or stopping treatment. During the reminder call, if patients reported the appearance of any adverse events, the same approach was followed. Those who missed their follow-up or opted to stop treatment were considered as dropouts, with reasons recorded.

Diagnosis according to ICD-1011 was established by a qualified psychiatrist through a clinical interview and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus.12 Patients were then prescribed antidepressant monotherapy (mirtazapine, sertraline, desvenlafaxine, escitalopram, or fluoxetine) at the discretion of the treating clinician. For the purpose of this study, the prescribed dose was deemed to be low if <15 mg/day for mirtazapine, <50 mg/day for sertraline, <25 mg/day for desvenlafaxine, <5 mg/day for escitalopram, and <10 mg/day for fluoxetine. Higher doses were deemed to be adequate.

Sexual function was assessed using the Psychotropic- Related Sexual Dysfunction Questionnaire (PRSexDQ),13 which comprises 2 introductory items and 5 items pertaining to sexual dysfunction and its tolerability. In each of the 5 items, a score of 0 indicates no dysfunction; scores of 1, 2, and 3 indicate dysfunction on ≤25%, 25%-75%, and >75% of occasions, respectively. The total score ranges from 0 to 15: scores 1-5 (with no item equal 2) indicate mild dysfunction, scores 6-10 (with any item equal 2 and no item equal 3) indicate moderate, and scores 11-15 (with any item equal 3) indicate severe. A PRSexDQ score of ≥2 was considered to indicate sexual dysfunction. Sexual dysfunction may be present before antidepressant treatment or it might be improved, worsened, or unchanged after antidepressant treatment. Thus, sexual function outcome was dichotomised to ‘favourable’ or ‘impaired’. Favourable sexual function was defined as no sexual dysfunction or improved sexual function relative to the previous visit. Impaired sexual function was defined as unchanged or worsened sexual dysfunction relative to the previous visit or new-onset sexual dysfunction.

Patients were also assessed using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,14 Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale,15 and Clinical Global Impression Severity and Improvement scales (CGI-S and CGI-I).16

Statistical Analysis

Last-observation-carried-forward analysis was not used because there was a possibility of change in sexual function between visits owing to either improvement in sexual function secondary to improved depression / anxiety or worsening sexual dysfunction secondary to antidepressant- emergent adverse effects. The chi-square test was used to compare proportions between groups. For variables that were not normally distributed, the Friedman test was used to compare changes in PRSexDQ score across time, and the Cochran test was used to compare changes in sexual function across time dichotomised as favourable or impaired. Backward-stepwise logistic regression analysis was used to determine predictors of sexual outcome at weeks 2 and 6; independent variables included age, gender, diagnosis, individual antidepressant, dose of antidepressant (low vs. adequate), PRSexDQ score, and CGI-S and CGI-I scores. All tests were two-sided. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 230 patients recruited, 209 (91%) were assessed at baseline: 123 women and 86 men, with a mean ± standard deviation (SD) age of 36.5 ± 12.7 years. All 209 patients (25 of them had stopped medication) were assessed at week 2, of whom 184 (30 of them had stopped medication) were also assessed at week 6 (Figure 1). Of the 209 patients, 138 (66%) were diagnosed with first-episode (n = 64), recurrent (n = 31), or dysthymia (n = 43) depressive disorder, and 71 (34%) were diagnosed with social (n = 20), generalised (n = 32), or panic (n = 19) anxiety disorder.

Patients were prescribed antidepressant monotherapy with mirtazapine (n = 28), sertraline (n = 56), desvenlafaxine (n = 37), escitalopram (n = 47), or fluoxetine (n = 41). Between baseline and week 2, the dose was deemed to be adequate in 28 (100%) patients prescribed mirtazapine, 2 (4%) prescribed sertraline, 26 (70%) prescribed desvenlafaxine, 26 (55%) prescribed escitalopram, and 15 (37%) prescribed fluoxetine. Overall, 46% of patients were taking an adequate dose. Between weeks 2 and 6, the dose was deemed adequate in 28 (100%) patients prescribed mirtazapine, 14 (25%) prescribed sertraline, 37

(100%) prescribed desvenlafaxine, 40 (85%) prescribed escitalopram, and 29 (71%) prescribed fluoxetine. Overall, 80% of patients were taking an adequate dose.

Adequacy of Treatment

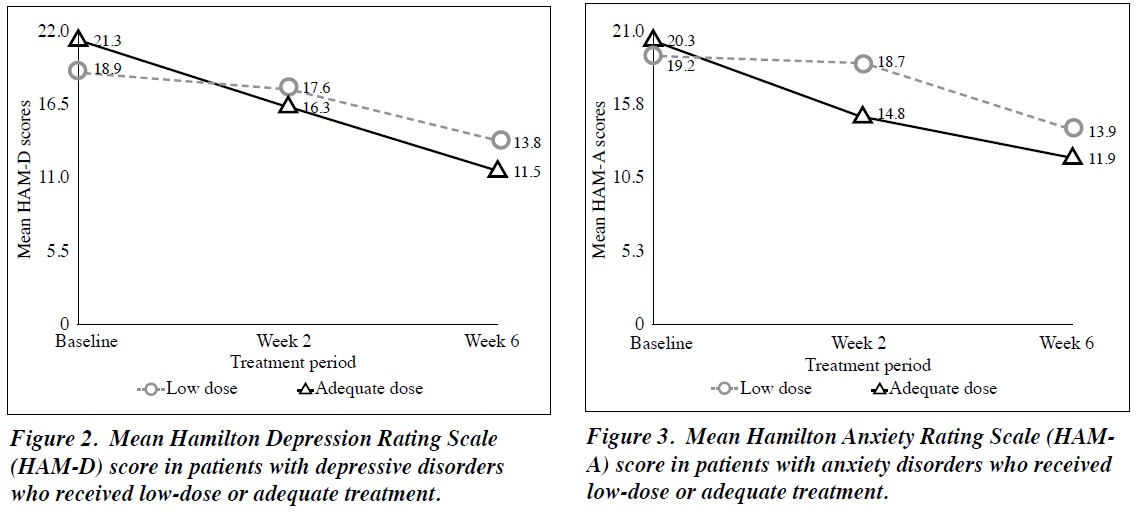

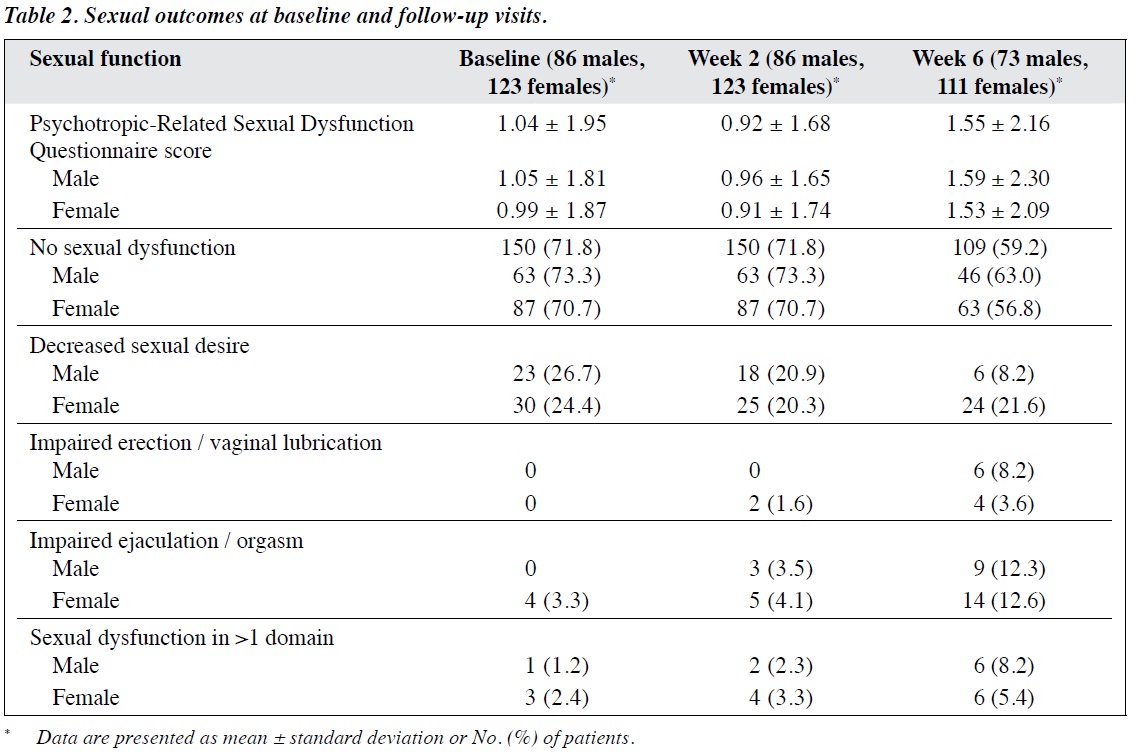

In patients with depressive disorders who received low- dose treatment, the mean ± SD Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score decreased from 18.9 ± 3.6 at baseline to 17.6 ± 3.2 at week 2 and 13.8 ± 4.2 at week 6; the corresponding values in those who received an adequate dose were 21.3 ± 3.5, 16.3 ± 3.9, and 11.5 ± 4.4 (Figure 2). In patients with anxiety disorders who received low-dose treatment, the mean ± SD Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale score decreased from 19.2 ± 3.0 at baseline to 18.7 ± 4.7 at week 2 and 13.9 ± 4.4 at week 6; the corresponding values in those who received an adequate dose were 20.3 ± 4.5, 14.8 ± 3.2, and 11.9 ± 4.6 (Figure 3). Patients who started treatment at an adequate dose seemed to have more severe illness at baseline and improve more at 2 weeks compared with those who started with low-dose treatment. Patients who started with low-dose treatment, however, seemed to narrow the difference in clinical score at 6 weeks when compared with the adequately treated group. Data were not inferentially analysed, because different patients were taking different doses at different time points.

Sexual Dysfunction

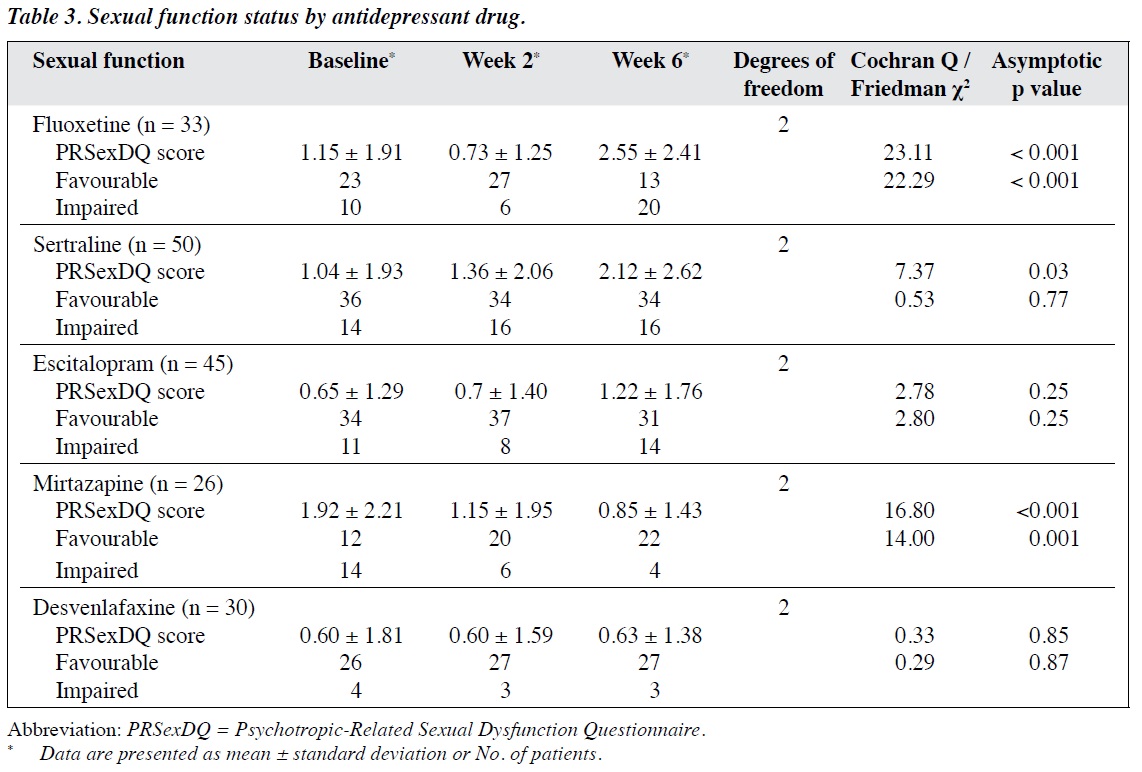

At baseline, 29% of patients had sexual dysfunction (in any domain of PRSexDQ). By week 6, the percentage had increased to 37% in men and 43% in women, with an overall of about 41% (35.3% + 5.4% of mild and moderate sexual dysfunction, respectively) [Table 1]. With regard to individual questionnaire items, by week 6, sexual desire improved, but erectile and ejaculatory function in men and orgasmic function in women worsened (Table 2). When sexual outcomes were dichotomised as favourable or impaired, there was a significant change across time in men (Cochran Q = 7.16; p = 0.03) but not in women (Cochran Q = 2.00; p = 0.37). The ratio of men with favourable sexual function to those with impaired sexual function increased from baseline (50 : 23) to week 2 (60 : 13) but decreased markedly by week 6 (49 : 24). In women, the ratio did not change significantly from baseline (82 : 29) to week 2 (85 : 26) or week 6 (78 : 23). Similarly, the changes in mean PRSexDQ score were significant for men (χ2 = 6.80; p = 0.03) but not for women (χ2 = 3.56; p = 0.17), although the

change was only marginal (from 1.04 at baseline to 1.55 at week 6) [Table 2].

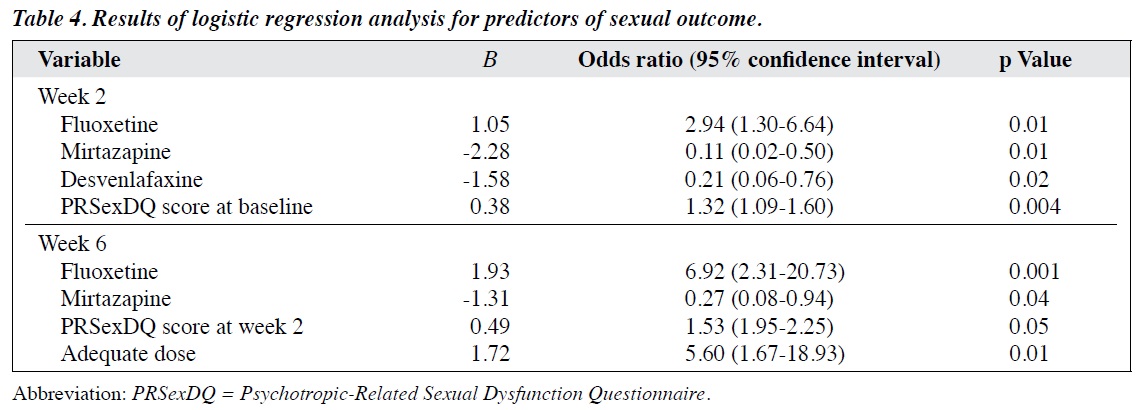

Fluoxetine and sertraline were associated with impaired sexual function, whereas mirtazapine was associated with favourable sexual function, and escitalopram and desvenlafaxine resulted in no changes (Table 3). In a logistic regression analysis, at week 2, mirtazapine and desvenlafaxine were predictors of favourable sexual outcome, whereas fluoxetine and higher baseline PRSexDQ score were predictors of impaired sexual outcome. At week 6, mirtazapine remained a predictor of favourable sexual outcome, whereas fluoxetine, higher 2-week PRSexDQ score, and adequate dose were predictors of impaired sexual outcome (Table 4).

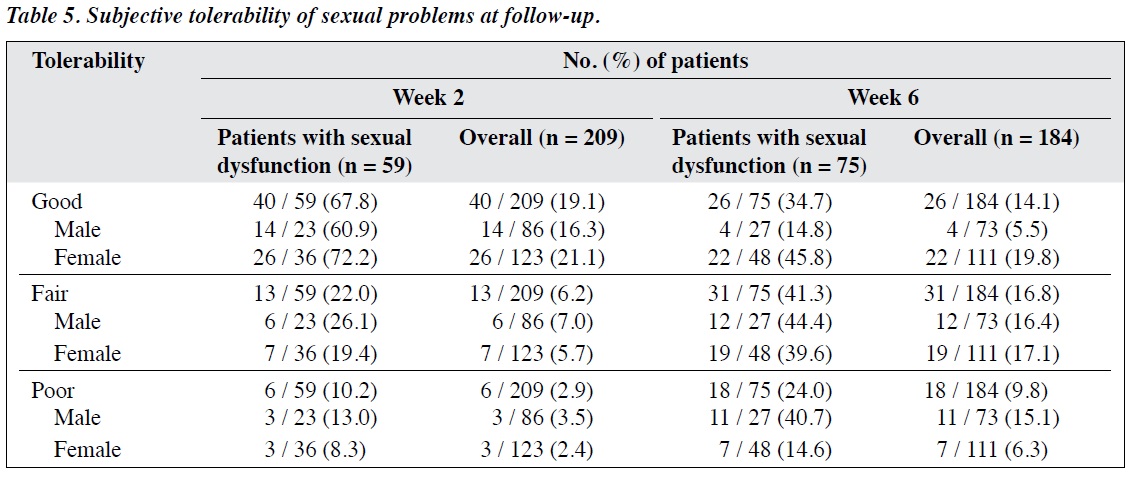

The proportion of patients who tolerated sexual problems poorly increased from 2.9% at week 2 to 9.8% at week 6; tolerability was poorer in men (increasing from 3.5% to 15.1%) than in women (increasing from 2.4% to

6.3%) [Table 5], and the difference in the proportions of men and women (15.1% vs. 6.3%) was significant at the trend level (χ2 = 3.831, degrees of freedom = 1; p = 0.05).

Discussion

In our study, 29% of patients had baseline sexual dysfunction (mostly decreased sexual desire). This finding enabled prospective evaluation of the prevalence of sexual dysfunction at weeks 2 and 6. Other studies have reported antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in about 40% to 60% of patients,5,17,18 but their data were cross-sectional. Most prospective studies of antidepressant-emergent sexual adverse effects either did not report the change in the overall prevalence of sexual dysfunction19,20 or excluded patients with baseline dysfunction.21 One study reported an unusual finding of low baseline orgasmic dysfunction.22

In our study, the change in sexual function from baseline to week 2 was negligible. By week 6, the prevalence of sexual dysfunction had increased by about 11%; the increase in the prevalence of mild and moderate sexual dysfunction was 12% and 1%, respectively. One study reported that the effects of antidepressants (bupropion and sertraline) on sexual function peaked at around week 4 and remained relatively stable until week 8.22 Similarly, another study reported improvement in sexual function with bupropion (300-450 mg/day) from week 5 onward.23 However, in our study, impaired sexual function with sertraline (50-150 mg/day) and fluoxetine (20-60 mg/day) was evident as early as week 2. For sertraline, it did not worsen much thereafter, whereas for fluoxetine the sexual dysfunction continued to increase until 6 weeks. None of our patients had severe sexual dysfunction during 6 weeks of treatment. We hypothesise 2 reasons for an increased rate of sexual dysfunction at week 6 (rather than week 2). One is that the resolution of anxiety or depression by 6 weeks might have increased interest in sexual activity, and thus awareness of any sexual problems might have become apparent by week 6 only. Another is that there were fewer patients at week 2 than week 6 in whom drug dose had been up-titrated to an adequate dose (46.4% vs. 80.4%). When the dose is adequate, antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction may emerge as early as by week 2.23

With regard to individual questionnaire items of sexual dysfunction, at week 6, the greatest increase in prevalence was for orgasmic dysfunction, followed by arousal dysfunction. This finding has been reported in other studies.17,19,24 Orgasmic delay is a known adverse effect of serotonin reuptake inhibitor,25 which is a component of 4 of the 5 antidepressants studied. Importantly, the mean PRSexDQ score worsened only marginally (from 1.04 at baseline to 1.55 at week 6). This change does not seem to be clinically significant,17 highlighting the importance of tolerance of sexual dysfunction. Nonetheless, 15 patients discontinued antidepressants owing to sexual adverse effects, accounting for 7% of 209 patients and 20% of those with sexual problems (n = 75). Had the 6-week PRSexDQ score been available for these 15 patients, the mean worsening in score might have been higher.

There is a possibility of gender-based pharmacokinetic differences in response to psychotropic drugs and the effect of physiological variation in sex-related hormones in women.26 In our study, at week 6, the increased prevalence of impaired sexual function was significant in male patients only. A possible explanation is that there was an increase in favourable sexual outcome at week 2 in men only. We thus considered that there may not be gender differences in overall sexual outcome, as gender was not a predictor of sexual function in logistic regression analysis. The decrease in impaired sexual desire at 6 weeks (from about 27% to 8%) and the development of erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction in men (from about 0% to 21%) also warrant further studies. Two Indian studies suggested worse sexual outcome in antidepressant-treated women (relative to men), but neither study used a longitudinal design.27,28

We found that the proportion of patients who tolerated sexual problems poorly increased from 2.9% at week 2 to 9.8% at week 6. The true value at week 6 could have been as high as 16.3% if data for the 15 patients who dropped out owing to sexual problems had been included. Tolerability was poorer in men (increased from 3.5% to 15.1%) than in women (increased from 2.4% to 6.3%). Although the gender difference was significant at the trend level only, worsening of the PRSexDQ score was significant in men only. In a large cross-sectional study of 10 antidepressants, a higher rate of poor tolerance (38%) was reported but there was no significant gender difference in tolerance to antidepressant- related sexual dysfunction.17

We found that fluoxetine and mirtazapine were associated with worsened and improved sexual outcomes, respectively. This finding refers to the change in intra-individual outcomes rather than between-drug comparisons.2,10,20,29,30 Higher (adequate) antidepressant doses were associated with greater sexual dysfunction; the dose-dependence of antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction has been reported,18,31 but it is not well established as a risk factor.10 Existing sexual dysfunction was a risk factor of antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction; this finding is consistent with that in a prospective study.20

Baseline severity of psychopathology and improvement in psychopathology have been reported to be associated with better sexual outcome in univariate analyses.20,21,32 It seems that the contribution of psychopathology, if any, is factored in when baseline sexual dysfunction or medication dose are considered.

Limitations

Our study had limitations. Patients were not randomised in terms of treatment, and thus between-drug comparisons could not be made. Nonetheless, within-drug comparisons revealed that mirtazapine was associated with favourable sexual outcome, and that fluoxetine was associated with impaired outcome. There was no placebo-controlled group; this limitation was partly offset by the longitudinal design, which could factor out the impact of baseline sexual dysfunction. However, the sample size was relatively large and included patients with or without sexual dysfunction at baseline; 91% of the sample provided reasons for dropout and 80% of sample remained at the 6-week follow-up. These aspects strengthen internal validity. Another study strength is the use of the structured PRSexDQ, which includes subjective tolerance of sexual dysfunction.

Although 5 commonly prescribed antidepressants were included, other newer antidepressants and other psychiatric disorders (e.g. obsessive-compulsive disorder) were not included in analysis. The lower than customary doses and slower-than-usual up-titration may have been further limitations, but efficacy outcome did not seem to be compromised. Nonetheless, this limitation helped identify the importance of dose in the prevalence and evolution of impaired sexual outcome. Finally, the study period was only 6 weeks, but there may have been further changes in sexual function across time. Other studies, however, have reported no change in sexual outcome at 8 weeks compared with 4 weeks22 and no change in sexual outcome at 8 months compared with 8 weeks.21 Those findings support the supposition that the effect of an antidepressant on sexual function should be evident within the first 6 weeks of treatment.

Conclusions

In patients with anxiety or depressive disorder, the risk of antidepressant-emergent sexual dysfunction at 6 weeks was low when drug doses were initially low and gradually up-titrated. Mirtazapine was associated with favourable sexual outcome, whereas fluoxetine was associated with impaired sexual outcome. Baseline sexual dysfunction was independently associated with impaired sexual outcome. Men may be more likely than women to experience impaired sexual outcome. In patients with baseline sexual dysfunction, prescription of mirtazapine might be preferred and that of fluoxetine avoided, particularly when up-titration of dose is planned.

Acknowledgement

The writing of this manuscript was supported by the Fogarty International Training Program in Chronic Non- Communicable Diseases and Disorders at the University of Florida (Grant No. 1D43TW009120).

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Lewis RW, Fugl-Meyer KS, Corona G, Hayes RD, Laumann EO, Moreira ED Jr, et al. Definitions / epidemiology / risk factors for sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2010;7(4 Pt 2):1598-607. cross ref

- La Torre A, Giupponi G, Duffy D, Conca A. Sexual dysfunction related to psychotropic drugs: a critical review — part I: antidepressants. Pharmacopsychiatry 2013;46:191-9. cross ref

- La Torre A, Conca A, Duffy D, Giupponi G, Pompili M, Grözinger M. Sexual dysfunction related to psychotropic drugs: a critical review part II: antipsychotics. Pharmacopsychiatry 2013;46:201-8. cross ref

- La Torre A, Giupponi G, Duffy DM, Pornpili M, Grözinger M, Kapfhammer HP, Conca A. Sexual dysfunction related to psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Part III: mood stabilizers and anxiolytic drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry 2014;47:1-6.

- Williams VS, Edin HM, Hogue SL, Fehnel SE, Baldwin DS. Prevalence and impact of antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in three European countries: replication in a cross-sectional patient survey. J Psychopharmacol 2010;24:489-96. cross ref

- Gregorian RS, Golden KA, Bahce A, Goodman C, Kwong WJ, Khan

- Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Ann Pharmacother 2002;36:1577-89. cross ref

- Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;29:259-66. cross ref

- Schweitzer I, Maguire K, Ng C. Sexual side-effects of contemporary antidepressants: review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:795-808. cross ref

- Reichenpfader U, Gartlehner G, Morgan LC, Greenblatt A, Nussbaumer B, Hansen RA, et al. Sexual dysfunction associated with second-generation antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder: results from a systematic review with network meta-analysis. Drug Saf 2014;37:19-31. cross ref

- Montgomery SA, Baldwin DS, Riley A. Antidepressant medications: a review of the evidence for drug-induced sexual dysfunction. J Affect Disord 2002;69:119-40. cross ref

- 1 World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1993.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59 Suppl 20:22-33.

- Montejo AL, Garcia M, Espada M, Rico-Villademoros F, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA. Psychometric characteristics of the psychotropic-related sexual dysfunction questionnaire. Spanish work group for the study of psychotropic-related sexual dysfunctions [in Spanish]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2000;28:141-50.

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56-62. cross ref

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959;32:50-5. cross ref

- Guy W. Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Scale. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology — Revised. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

- Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, Rico-Villademoros F. Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62 Suppl 3:10-21.

- Clayton AH, Pradko JF, Croft HA, Montano CB, Leadbetter RA, Bolden-Watson C, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among newer antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:357-66. cross ref

- Labbate LA, Grimes JB, Arana GW. Serotonin reuptake antidepressant effects on sexual function in patients with anxiety disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1998;43:904-7. cross ref

- Khazaie H, Rezaie L, Rezaei Payam N, Najafi F. Antidepressant- induced sexual dysfunction during treatment with fluoxetine, sertraline and trazodone; a randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2015;37:40-5. cross ref

- Clayton A, Kornstein S, Prakash A, Mallinckrodt C, Wohlreich M. Changes in sexual functioning associated with duloxetine, escitalopram, and placebo in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. J Sex Med 2007;4:917-29. cross ref

- Coleman CC, Cunningham LA, Foster VJ, Batey SR, Donahue RM, Houser TL, et al. Sexual dysfunction associated with the treatment of depression: a placebo-controlled comparison of bupropion sustained release and sertraline treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1999;11:205-48. cross ref

- Thase ME, Clayton AH, Haight BR, Thompson AH, Modell JG, Johnston JA. A double-blind comparison between bupropion XL and venlafaxine XR: sexual functioning, antidepressant efficacy, and tolerability. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26:482-48. cross ref

- Corona G, Ricca V, Bandini E, Mannucci E, Lotti F, Boddi V, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor–induced sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2009;6:1259-69. cross ref

- Werneke U, Northey S, Bhugra D. Antidepressants and sexual dysfunction. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2006;114:384-97. cross ref

- Romans SE. Gender issues in psychiatry. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2000;10:7-11.

- Grover S, Shah R, Dutt A, Avasthi A. Prevalence and pattern of sexual dysfunction in married females receiving antidepressants: An exploratory study. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2012;3:259-65. cross ref

- Krishna K, Avasthi A, Grover S. Prevalence and psychological impact of antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a study from North India. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;31:457-62. cross ref

- Behnke K, Søgaard J, Martin S, Bäuml J, Ravindran AV, Agren H, et al. Mirtazapine orally disintegrating tablet versus sertraline: a prospective onset of action study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23:358-64. cross ref

- Wade A, Crawford GM, Angus M, Wilson R, Hamilton L. A randomized, double-blind, 24-week study comparing the efficacy and tolerability of mirtazapine and paroxetine in depressed patients in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;18:133-41.

- Sidi H, Asmidar D, Hod R, Guan NC. Female sexual dysfunction in patients treated with antidepressant-comparison between escitalopram and fluoxetine. J Sex Med 2012;9:1392-9. cross ref

- Michelson D, Schmidt M, Lee J, Tepner R. Changes in sexual function during acute and six-month fluoxetine therapy: a prospective assessment. J Sex Marital Ther 2001;27:289-302. cross ref