East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2022;32:57-61 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2227

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Athena KY Chan, Department of Psychiatry, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong SAR

Terence TY Yeung, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong SAR

Min-Yi Sum, Department of Psychiatry, The LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR

Jessie SC Xiong, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR

Sherry KW Chan, Department of Psychiatry, The LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR

Kin-Shing Cheng, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong SAR

Address for correspondence: Sherry KW Chan, Department of Psychiatry, The LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR. Email: kwsherry@hku.hk

Submitted: 11 May 2022; Accepted: 5 August 2022

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the Mental Health Youth Ambassador Programme between 2016 and 2019 in terms of participants’ improvement in attitudes towards individuals with depression or psychosis. Methods: This anti-stigma programme was provided to secondary students (form 3 and above) and comprised three levels. Level 1 involved attending lectures about mental health; level 2 and level 3 involved social contact with persons-in-recovery. Students’ attitudes towards those with depression and those with psychosis were assessed at baseline and after completion of each level of programme using the Chinese version of the Social Distance Scale.

Results: Only 25 students who were assessed at all four time points were included in analysis. The mean Social Distance Scale scores for attitudes towards depression and psychosis improved significantly across all time points. Specifically, significant improvement occurred after completion of level 2 and level 2 but not after completion of level 1.

Conclusion: Social contact with people with mental illness (rather than attending lectures about mental health) contributed significantly to the improvement in students’ attitude towards depression and psychosis. With the positive preliminary results, the Mental Health Youth Ambassador Programme should be extended to more students.

Key words: Adolescent; Mental health; Social stigma

Introduction

Stigma comprises three components: stereotype, prejudice, and discrimination. Stereotype is a means of categorising social groups and is considered a belief, whereas prejudice is an attitude with a negative component. Stereotype and prejudice can lead to the behavioural reaction of discrimination (the act of exclusion or rejection).1 Stigmatisation and discrimination (of people with mental illness) can adversely affect such peoples’ personal relationship, education, work, and accessibility to healthcare resources as well as their family member and carers.2 In Hong Kong, stigma about psychosis and mental health illness is high, particularly among the younger population.3,4

Anti-stigmatisation should be included when promoting mental health in the community.

According to the World Health Organization, mental health promotion involves creating environments that support mental health and allowing people to adopt lifestyles for mental wellbeing. This involves the health sector, the legislation sector to implement policies to safeguard the fundamental civil and socio-economic rights of people with mental illness, and the education sector to promote mental health, in particular interventions to reduce stigma towards individuals with mental illness for young people.5

Educational programmes for young people are effective in promoting the awareness of mental health and in improving attitudes towards those with mental health issues.6 Such benefits remain significant in long term.7-13

For mental health promotion to be effective, interventions must have adequate support and be consistent, rigorous, and faithful in attaining its goals.14 In addition, social contact– based interventions for students should be included,2 because young people can have a positive change in level of stigma and discrimination towards people with mental illness by interacting with them and listening to their sharing.15

This study aims to evaluate the Mental Health Youth Ambassador Programme between 2016 and 2019 in terms of

participants’ improvement in attitudes towards individuals with depression or psychosis.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (reference: UW 21-109). Since 2016, the Mental Health Youth Ambassador Programme has been implemented by the Public Awareness Committee of the Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists. This anti-stigma programme is provided to secondary students (form 3 and above) who are interested in promoting mental health in the community or pursuing a career related to mental health in future. All secondary schools in Hong Kong are invited to participate. The programme aims to promote the understanding of mental illness and to reduce the stigma to mental illness by providing opportunities of personal contact with individuals with mental illness and by allowing students to organise programme to promote mental health awareness.

There are three levels of participation. At level 1 (one star), students attend at least three lectures organised by the Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists or other associations about various mental disorders, common myths, and stigma and discrimination issues. Topics include common mental disorders (depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder), severe mental illness (psychosis, bipolar affective disorder), old-age psychiatry (dementia, elderly depression), child and adolescent psychiatry (autism, attention-deficit hyperactive disorder), and alcohol and substance abuse problems, as well as ways to promote mental health and wellness.

At level 2 (two stars), students volunteer to participate in services to persons-in-recovery organised by the programme or in collaboration with non-government organisations such as Mental Health Association, New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association, Baptist Oi Kwan Social Service, Richmond Fellowship of Hong Kong Radio i-care of Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, and Caritas Hong Kong. Participants also work with persons-in-recovery to provide services to other groups such as the older people. Those who achieve 20 hours of volunteer work are awarded two stars.

At level 3 (three stars), students organise projects to promote mental health to the general public or to provide service to persons-in-recovery. Participants work in groups and submit proposals to organisers who oversee the projects. Examples include a project for stress management among students and an event for mental health awareness to the general public. Participants who completed the project are awarded three stars.

Students usually take 1 year to complete all three levels. Students who are more interested in mental health are expected to participate in higher levels of programme, and thus fewer participants are expected in higher levels of programme. Achievers of three stars may join an attachment programme to the department of psychiatry of local universities or hospitals. Participants with outstanding performance are enrolled to a mentorship programme with psychiatrists as mentors.

Students’ attitudes towards those with depression and those with psychosis was assessed at baseline and after completion of each level of programme using the Chinese version of the Social Distance Scale,16,17 which comprises seven items measured in a four-point Likert scale. Its internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) is 0.92.17 The Chinese version was modified for secondary students by changing the question “whether the respondent is interested to work with a patient” to “whether the respondent is interested to be a classmate of a patient”.16 Higher scores indicate more willing to participate in social contacts with individuals with mental illness.

Characteristics of those who completed level 1 and those with missing data were compared using the Mann- Whitney U test or Chi-squared test, as appropriate. Only students who were assessed at all four time points were included in further analysis. Non-parametric tests were used owing to the small sample size. Students’ attitude towards depression and psychosis across all four time points was compared using the Friedman test, followed by pairwise comparisons of different time points using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS (Windows version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). A p value (two-tailed) of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons.

Results

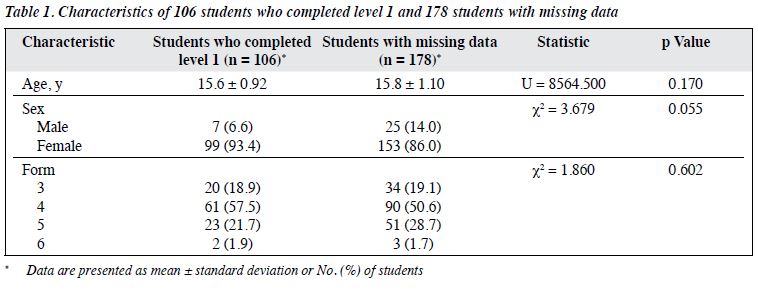

Between 2016 and 2019, 340 students enrolled in the programme. 329 (96.8%) of them were assessed for their attitudes towards depression and psychosis. Of the 340 students, 226, 65, and 48 completed level 1, level 2, and level 3, respectively. Of those who completed level 1, level 2, and level 3, 106 (46.9%), 42 (64.6%), and 29 (60.4%), respectively, were assessed again for their attitudes towards depression and psychosis. 106 students (93.4% were female and 57.5% were in form 4) who completed level 1 were compared with 178 students with missing data. The two groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, and form level (Table 1).

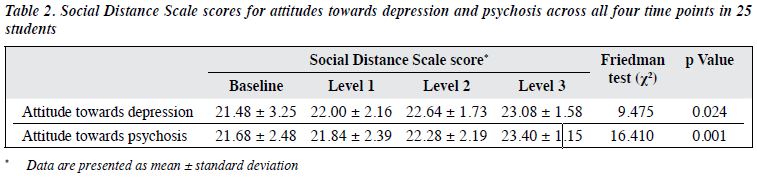

Only 25 students completed all three levels and were assessed at all four time points. The mean Social Distance Scale scores for attitudes towards depression and psychosis improved significantly across all time points (Table 2).

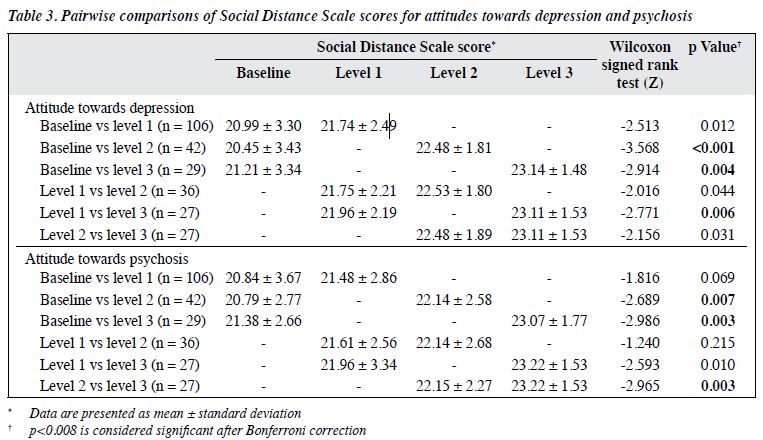

In pairwise comparisons after Bonferroni correction, the Social Distance Scale scores for attitudes towards depression and psychosis improved significantly after completion of level 2 and level 3 but not after completion of level 1 (Table 3). The attitude towards psychosis (but not depression) improved significantly from completion of level 2 to completion of level 3.

Discussion

Students’ attitudes towards depression and psychosis improved significantly after completion of all three levels of the Mental Health Youth Ambassador Programme. Specifically, significant improvement occurred after completion of level 2 and level 3 but not after completion of level 1 (attending lectures). Significant improvement occurred from completion of level 2 to completion of level 3 for attitude towards psychosis but not for attitude towards depression. Our findings suggest that longer and more in- depth involvement and contribution to the anti-stigma programme result in more improvement in attitudes towards depression and psychosis among students.

Most anti-stigma programmes involve education- alone or contact-alone interventions or both.18,19 In the present study, significant improvement in attitudes towards depression and psychosis occurred after social contact with persons-in-recovery but not after attending a series of mental health lectures. Social contact with those with mental illness is the key component to improve attitude toward mental illness among the general population.13

Combining education with direct or indirect social contact is more effective to improve attitudes of high-school students, compared with education alone.20,21 Social contact decreases the desire for imposing social distance and social restrictions on those diagnosed with serious mental illness22 and improves people’s willingness to care for individuals with mental illness.23

In the present study, attending ≥3 lectures on mental illnesses alone could not significantly improve students’ attitude towards mental illness. This finding is in contrast with that in previous studies.8,24-26 One possible reason may be related to the lack of sensitivity in our questionnaire, which focused mainly on the attitudes towards depression and psychosis. Students might have attended lectures on mental illnesses other than depression and psychosis. In addition, the information provided in the lectures was not assessed. Education campaigns that provide information on genetic components of schizophrenia may reduce the blame placed on people with mentally illness.27 However, this may unintentionally enhance the notion of ‘differentness’ of people with mentally illness, aggravating anticipations of unexpected behaviour and diverting attention from the possibility of recovery, which in turn intensified negative attitudes and behaviour.27 The small sample size may limit the power of the study to detect the improvement. Nonetheless, attending lectures on mental illnesses still has value on reducing stigmatisation, as subsequent activities were built on top of the education component. Education followed by contact-based interventions is more effective in improving attitudes among high school students, compared with education alone.20

The present study has several limitations. The sample size was small, especially for those who completed all three levels of the programme and were assessed across all four time points. Students who completed level 2 and level 3 were more likely to change their attitudes and beliefs. This might result in a bias towards a favourable outcome of the programme. There may have been a social desirability bias, as the questionnaire was self-reported and respondents may tend to provide socially desirable answers. Comparison with a control group was not performed owing to pragmatic constraints.

Conclusions

Social contact with people with mental illness (rather than attending lectures about mental health) contributed significantly to the improvement in students’ attitudes towards depression and psychosis. With the positive preliminary results, the Mental Health Youth Ambassador Programme should be extended to more students.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

AKY Chan was the Mental Health Youth Ambassador Taskforce Convener. TTY Yeung, JSC Xiong, and SKW Chan were Taskforce members. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (reference: UW 21-109).

References

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2002;9:35-53. Crossref

- Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet 2016;387:1123-32. Crossref

- Chan SK, Tam WW, Lee KW, et al. A population study of public stigma about psychosis and its contributing factors among Chinese population in Hong Kong. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2016;62:205-13. Crossref

- Lo LLH, Suen YN, Chan SKW, et al. Sociodemographic correlates of public stigma about mental illness: a population study on Hong Kong’s Chinese population. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:274. Crossref

- World Health Organization. Mental Health: Strengthening our Response. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact- sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response.

- Wells J, Barlow J, Stewart-Brown S. A systematic review of universal approaches to mental health promotion in schools. Health Educ 2003;103:197-220. Crossref

- Corrigan P, Michaels PJ, Morris S. Do the effects of antistigma programs persist over time? Findings from a meta-analysis. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:543-6. Crossref

- Pinfold V, Toulmin H, Thornicroft G, Huxley P, Farmer P, Graham T. Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:342-6. Crossref

- Schulze B, Richter-Werling M, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Crazy? So what! Effects of a school project on students’ attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003;107:142-50. Crossref

- Wong PWC, Arat G, Ambrose MR, Xie KQ, Borschel M. Evaluation of a mental health course for stigma reduction: a pilot study. Cogent Psychol 2019;6:1595877. Crossref

- Fung E, Lo TL, Chan RW, Woo FC, Ma CW, Mak BS. Outcome of a knowledge contact-based anti-stigma programme in adolescents and adults in the Chinese population. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2016;26:129-36.

- Fang Q, Zhang TM, Wong YLI, et al. The mediating role of knowledge on the contact and stigma of mental illness in Hong Kong. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2021;67:935-45. Crossref

- Hui CLM, Leung WWT, Wong AKH, et al. Destigmatizing psychosis: investigating the effectiveness of a school-based programme in Hong Kong secondary school students. Early Interv Psychiatry 2019;13:882-7.Crossref

- Langford R, Bonell CP, Jones HE, et al. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;4:CD008958. Crossref

- Pinfold V, Thornicroft G, Huxley P, Farmer P. Active ingredients in anti-stigma programmes in mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry 2005;17:123-31. Crossref

- Chow Y. Stigma towards individuals with mental illness: a comparison of staff members of two non-governmental organizations and a mental hospital in Hong Kong [unpublished observations].

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF. The social rejection of former mental patients: Understanding why labels matter. Am J Sociol 1987;92:1461-1500. Crossref

- Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, et al. Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophr Bull 2001;27:187-95. Crossref

- Gronholm PC, Henderson C, Deb T, Thornicroft G. Interventions to reduce discrimination and stigma: the state of the art. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017;52:249-58. Crossref

- Chan JY, Mak WW, Law LS. Combining education and video-based contact to reduce stigma of mental illness: “The Same or Not the Same” anti-stigma program for secondary schools in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1521-6. Crossref

- Meise U, Sulzenbacher H, Kemmler G, Schmid R, Roessler W, Guenther V. [“…not dangerous, but nevertheless frightening”. A program against stigmatization of schizophrenia in schools [in German]. Psychiatr Prax 2000;27:340-6.

- Covarrubias I, Han M. Mental health stigma about serious mental illness among MSW students: social contact and attitude. Soc Work 2011;56:317-25. Crossref

- Gu L, Xu D, Yu M. Mediating effects of stigma on the relationship between contact and willingness to care for people with mental illness among nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2021;103:104973. Crossref

- Lanfredi M, Macis A, Ferrari C, et al. Effects of education and social contact on mental health-related stigma among high-school students. Psychiatry Res 2019;281:112581. Crossref

- Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rusch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:963-73. Crossref

- Watson AC, Otey E, Westbrook AL, et al. Changing middle schoolers’ attitudes about mental illness through education. Schizophr Bull 2004;30:563-72. Crossref

- Schomerus G, Schwahn C, Holzinger A, et al. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2012;125:440-52. Crossref