East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2024;34:3-8 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2255

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Jalal Doufik, Laila Lahlou, Mustafa al’Absi, Jamaleddine Benhamida, Hicham Laaraj, Mina Ouhamou, Omar El oumary, Zineb Salehddine, Khalid Mouhadi, Ismail Rammouz

Abstract

Background: During the COVID-19 pandemic, social-distancing and confinement measures were implemented. These may affect the mental health of patients with mental disorders such as schizophrenia. This study examined the clinical course of patients with schizophrenia at a public hospital in Morocco during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: This longitudinal observational study was conducted across three periods in 15 months: 1 April 2020 (start of strict home confinement) to 30 June 2020 (T1), 1 July 2020 to 31 January 2021 (corresponding to the Delta wave) [T2], and 1 February 2021 to 30 June 2021 (corresponding to the Omicron wave) [T3]. Patients aged 18 to 65 years with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (based on DSM 5) made before the pandemic who presented to the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Rabat were invited to participate. Psychotic symptomatology was evaluated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Severity and improvement of mental disorder were evaluated using the Clinical Global Impression (CGI)-Severity and -Improvement subscales. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Calgary Depression Scale (CDS). Adherence to treatments was assessed using the Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS). All assessments were made by psychiatrists or residents face-to-face (for T1) or via telephone (for T2 and T3).

Results: Of 146 patients recruited, 83 men and 19 women (mean age, 39 years) completed all three assessments. The CGI-Severity score was higher at T2 than T1 and T3 (3.24 vs 3.04 vs 3.08, p = 0.041), and the MARS score was higher at T1 and T2 than T3 (6.80 vs 6.83 vs 6.35, p = 0.033). Patient age was negatively correlated with CDS scores for depressive symptoms at T1 (Spearman’s rho = −0.239, p = 0.016) and at T2 (Spearman’s rho = −0.231, p = 0.019). The MARS score for adherence was higher in female than male patients at T1 (p = 0.809), T2 (p = 0.353), and T3 (p = 0.004). Daily tobacco consumption was associated with the PANSS total score at T3 (p = 0.005), the CGI-Severity score at T3 (p = 0.021), and the MARS score at T3 (p = 0.002). Patients with a history of attempted suicide had higher CDS scores than those without such a history at T1 (p = 0.015) and T3 (p = 0.018) but not at T2 (p = 0.346).

Conclusion: Home confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic had limited negative impact on the mental health of patients with schizophrenia in Morocco.

Key words: COVID-19; Longitudinal studies; Observational study; Schizophrenia

Jalal Doufik, Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, REGNE Research Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco

Laila Lahlou, Laboratory of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco

Mustafa al’Absi, Department of Family Medicine and Biobehavioral Health, University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth, Minneapolis, United States

Jamaleddine Benhamida, Department of Family Medicine and Biobehavioral Health, University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth, Minneapolis, United States

Hicham Laaraj, Department of Psychiatry. Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco

Mina Ouhamou, Department of Psychiatry. Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco

Omar El oumary, Department of Psychiatry. Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco

Zineb Salehddine, Department of Psychiatry. Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco

Khalid Mouhadi, Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, REGNE Research Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco

Ismail Rammouz, Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, REGNE Research Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco

Submitted: 4 November 2022; Accepted: 11 December 2023

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Morocco declared a state of emergency on 20 March 2020 and required closure of establishments, ceasing all but essential activity, and home confinement of the population (which ended on 28 May 2020). Unlike other countries, Morocco experienced only two waves: the first between August 2020 and January 2021 and the second between July 2021 and October 2021.

Home confinement can result in deleterious psychological impacts such as mood disorders, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder. Such risk increases with the duration of isolation, along with poor housing conditions, loss of income, lack of information, and boredom. Different people have varying degrees of adaptation to confinement, depending on underlying personality traits and the presence of a psychiatric disorder.1

Patients with schizophrenia have less access to information, worry excessively about contagion, are more susceptible to infection, and have poorer COVID-19– related outcomes including increased mortality.2-4 Psychotic relapse is associated with non-adherence to treatment, comorbid depression, substance abuse, and stressful life events.5 In patients with schizophrenia, social isolation may increase suicide risk,6 and increased stress is associated with aggressive behaviour.7 Stressors can aggravate symptoms even patients adhere treatment adequately.8 The impact of social distancing is greater on patients with schizophrenia due to their greater needs for community services and income support.9 This study examined the clinical course of patients with schizophrenia at a public hospital in Morocco during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This longitudinal observational study was conducted across three periods in 15 months: 1 April 2020 (start of strict home confinement) to 30 June 2020 (T1), 1 July 2020 to 31 January 2021 (corresponding to the Delta wave) [T2], and 1 February 2021 to 30 June 2021 (corresponding to the Omicron wave) [T3]. Patients aged 18 to 65 years with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (based on DSM 5) made before the pandemic who presented to the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Rabat were invited to participate. Patients were excluded if they had brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder/paranoia, psychotic disorder due to a medical condition or induced by substance/medication, or neurological or neurodegenerative disorders.

Patients’ sociodemographic and clinical data were collected, including personal history, substance use status, home environment, number of household members, and whether they or their family members had been infected with COVID-19. Psychotic symptomatology was evaluated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).10 Severity and improvement of mental disorder were evaluated using the Clinical Global Impression (CGI)-Severity and -Improvement subscales.11 Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Calgary Depression Scale (CDS).12 Adherence to treatments was assessed using the Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS).13 All assessments were made by psychiatrists or residents face- to-face (for T1) or via telephone (for T2 and T3).

Jamovi software (www.jamovi.org/) was used for statistical analyses. Data distribution was determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Quantitative variables with normal distribution were compared using the Student’s t test. Qualitative variables with normal distribution were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Qualitative variables with non-normal distribution were compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For comparisons of more than two groups, a Kruskal-Wallis test or repeated measures analysis of variance was used.

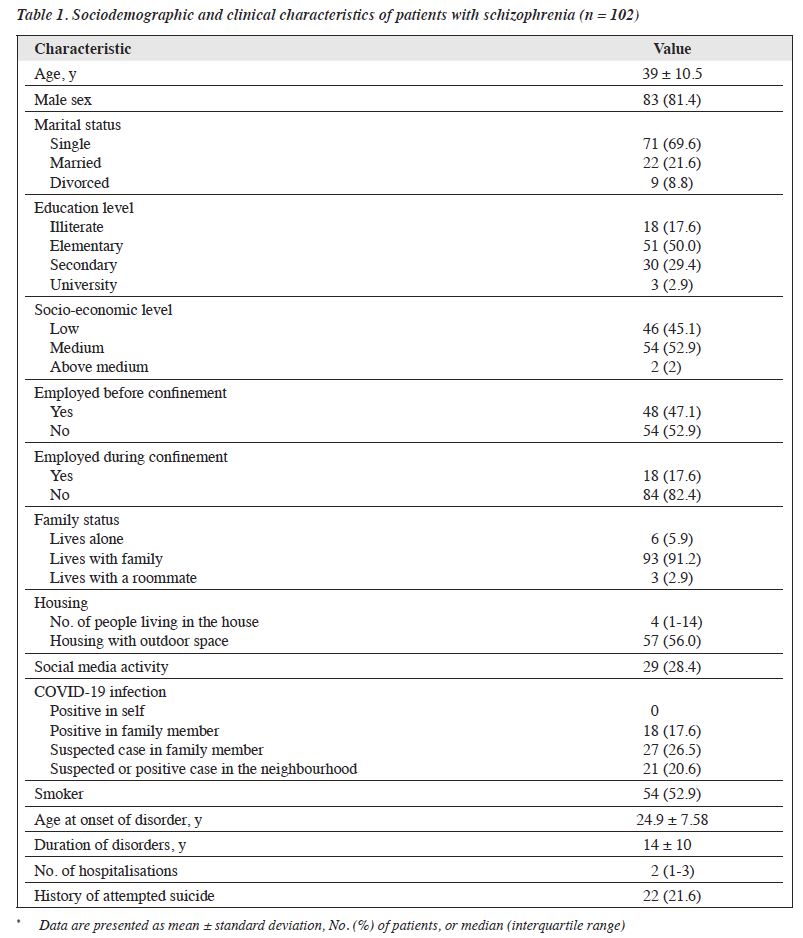

Of 146 patients recruited, 83 men and 19 women (mean age, 39 years) completed all three assessments (Table 1). Most patients were single (69.6%), smokers (52.9%), living with their families (91.2%), and unemployed during the confinement period (82.4%). No patient had COVID-19 infection, and 18 patients had family members infected.

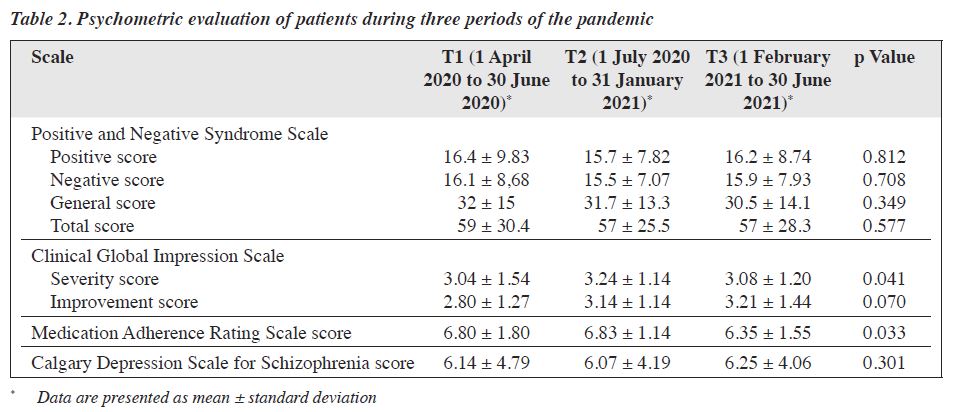

The CGI-Severity score was higher at T2 than T1 and T3 (3.24 vs 3.04 vs 3.08, p = 0.041), and the MARS score was higher at T1 and T2 than T3 (6.80 vs 6.83 vs 6.35, p = 0.033) [Table 2]. Scores of other evaluations did not differ significantly between the three periods.

Patient age was negatively correlated with CDS scores for depressive symptoms at T1 (Spearman’s rho = −0.239, p = 0.016) and at T2 (Spearman’s rho = −0.231, p = 0.019). The MARS score for adherence was higher in female than male patients at T1 (p = 0.809), T2 (p = 0.353), and T3 (p = 0.004). Daily tobacco consumption was associated with the PANSS total score at T3 (p = 0.005), the CGI-Severity score at T3 (p = 0.021), and the MARS score at T3 (p = 0.002). Patients with a history of attempted suicide had higher CDS scores than those without such a history at T1 (p = 0.015) and T3 (p = 0.018) but not at T2 (p = 0.346).

Although a systematic review reported deterioration of mental health in the general population and in patients with mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic,14 the present study did not find any association between the pandemic and an overall increase in relapses among patients with schizophrenia in Morocco. Younger patients were at greater risk of having depressive symptoms at T1 and T2; this could be due to less tolerance to the social- distancing measures. Female patients were more adherent to medication regimens. There was no correlation between patient sex and PANSS, CGI, or CDS scores, probably owing to the small sample size of female patients, although one study reported higher levels of wellbeing in women than men during the pandemic.15

It is controversial about the association between smoking status, psychiatric symptoms, and extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia. A meta-analysis in 2019 concluded that smoking was not associated with changes in depressive, anxiety, and negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. However, smoking was found to increase the intensity of positive symptoms and alleviate extrapyramidal side effects.16 Tobacco use was found to be associated with higher levels of physical aggression and suicidal behaviour.17,18

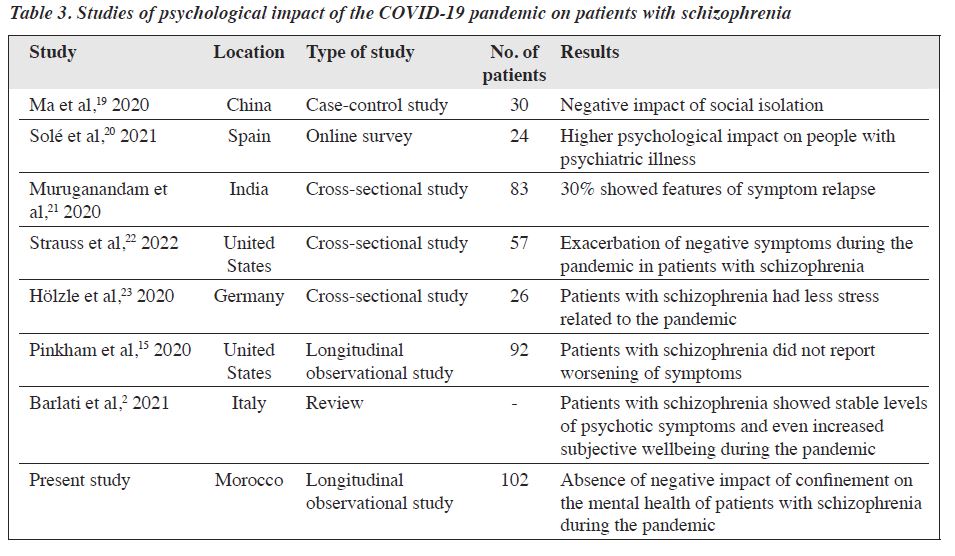

Table 3 shows studies of the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with schizophrenia.2,15,19-23 In a study at the Wuhan Hospital in 2020 examining the psychological impact of quarantine on patients with schizophrenia, scores of the Chinese Perceived Stress Scale, the Hamilton Depression Scale, and the Hamilton Anxiety Scale were higher in those under quarantine than in those without quarantine.19 Similarly, a study in Spain with 619 participants (206 of whom had depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, or schizophrenia and related disorders) revealed that levels of self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression during confinement were higher in patients with psychiatric illness than in the general population.20 In a study of 132 patients with severe mental disorders (59.1% had schizophrenia and 3.8% had schizoaffective disorder), 30% of patients had a relapse of psychiatric symptoms during the confinement period.21 Compared with pre-pandemic levels, severity of negative symptoms increased substantially during the pandemic, with exacerbation of anhedonia, avolition, and asociality.22 A study in Germany found that patients with affective disorder reported greater stress related to COVID-19 than patients with schizophrenia; this was hypothesised to be due to the protective role of preoccupation with severe intrinsic problems in patients with schizophrenia.23 Similarly, social isolation and physical distancing affect patients with schizophrenia differently, as these patients may have already led solitary lives. The low levels of worry and awareness in patients with schizophrenia may have contributed to their stability. In a longitudinal observational study of 92 patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder and 56 patients with affective disorders between April 2020 and June 2020, patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder remained stable over time in terms of severity of affective experiences, psychotic symptoms, and sleep disturbances.15 During the pandemic, severity of psychotic symptoms was stable among patients with schizophrenia, and subjective wellbeing did not deteriorate significantly; this is likely due to the autistic characteristics and tendency that characterise patients with schizophrenia.2 In the present study, the impact of social isolation may have been mitigated, as 91% of patients were living with their family (with a mean of four people per household) and 56% of patients were living in dwellings with an outdoor space. Furthermore, 72% of patients were not active on social media, which is a source of exacerbation of mental disorders.24 In addition, no patient was infected and only 17.6% of patients had family members infected; this may have introduced bias.

There are limitations to the present study. 30% of patients were lost to follow-up because of the confinement measures and the heavy workload of the healthcare teams. These patients may have changed their care provider and treated by psychiatrists in the private sector. Many patients were considered in remission by their families, and their prescriptions were renewed without assessment. The sample was recruited in a single institution and is not representative of the Moroccan population. The sample size of female patients is small; this may reflect a cultural reality that the demand for care and hospitalisation among women with psychotic disorders is low. Indeed, >80% of hospital admissions are for male patients.

Home confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic had limited negative impact on the mental health of patients with schizophrenia in Morocco.

JD, KM, and IR designed the study. JD, HL, MO, OE, ZS, KM, and IR acquired the data. LL analysed the data. JD, MA, JB, and IR drafted the manuscript. JD and IR critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Mohammed V University, Rabat, Morocco (reference: CERB D-23). The patients were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020;395:912-20. Crossref

- Barlati S, Nibbio G, Vita A. Schizophrenia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2021;34:203-10. Crossref

- Nemani K, Li C, Olfson M, et al. Association of psychiatric disorders with mortality among patients with COVID-19. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:380-6. Crossref

- Tzur Bitan D, Krieger I, Kridin K, et al. COVID-19 prevalence and mortality among schizophrenia patients: a large-scale retrospective cohort study. Schizophr Bull 2021;47:1211-7. Crossref

- Kazadi N, Moosa M, Jeenah FY. Factors associated with relapse in schizophrenia. S Afr J Psychiatry 2008;14:52-62. Crossref

- Montross LP, Zisook S, Kasckow J. Suicide among patients with schizophrenia: a consideration of risk and protective factors. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2005;17:173-82. Crossref

- Volavka J, Citrome L. Pathways to aggression in schizophrenia affect results of treatment. Schizophr Bull 2011;37:921-9. Crossref

- Fusar-Poli P, Tantardini M, De Simone S, et al. Deconstructing vulnerability for psychosis: meta-analysis of environmental risk factors for psychosis in subjects at ultra high-risk. Eur Psychiatry 2017;40:65-75. Crossref

- Hakulinen C, Elovainio M, Arffman M, et al. Employment status and personal income before and after onset of a severe mental disorder: a case-control study. Psychiatr Serv 2020;71:250-5. Crossref

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987;13:261-76. Crossref

- Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4:28- 37.

- Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the Calgary Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1993;22:39-44. Crossref

- Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res 2000;42:241-7. Crossref

- Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun 2020;89:531-42. Crossref

- Pinkham AE, Ackerman RA, Depp CA, Harvey PD, Moore RC. A longitudinal investigation of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of individuals with pre-existing severe mental illnesses. Psychiatry Res 2020;294:113493. Crossref

- Huang H, Dong M, Zhang L, et al. Psychopathology and extrapyramidal side effects in smoking and non-smoking patients with schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2019;92:476-82. Crossref

- Mallet J, Le Strat Y, Schurhoff F, et al. Tobacco smoking is associated with antipsychotic medication, physical aggressiveness, and alcohol use disorder in schizophrenia: results from the FACE-SZ national cohort. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019;269:449-57. Crossref

- Cassidy RM, Yang F, Kapczinski F, Passos IC. Risk factors for suicidality in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 96 studies. Schizophr Bull 2018;44:787-97. Crossref

- Ma J, Hua T, Zeng K, Zhong B, Wang G, Liu X. Influence of social isolation caused by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the psychological characteristics of hospitalized schizophrenia patients: a case-control study. Transl Psychiatry 2020;10:411. Crossref

- Solé B, Verdolini N, Amoretti S, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Spain: comparison between community controls and patients with a psychiatric disorder. Preliminary results from the BRIS-MHC STUDY. J Affect Disord 2021;281:13-23. Crossref

- Muruganandam P, Neelamegam S, Menon V, Alexander J, Chaturvedi SK. COVID-19 and severe mental illness: impact on patients and its relation with their awareness about COVID-19. Psychiatry Res 2020;291:113265. Crossref

- Strauss GP, Macdonald KI, Ruiz I, Raugh IM, Bartolomeo LA, James SH. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis and outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2022;272:17-27. Crossref

- Hölzle P, Aly L, Frank W, Förstl H, Frank A. COVID-19 distresses the depressed while schizophrenic patients are unimpressed: a study on psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res 2020;291:113175. Crossref

- Zhong B, Huang Y, Liu Q. Mental health toll from the coronavirus: social media usage reveals Wuhan residents’ depression and secondary trauma in the COVID-19 outbreak. Comput Hum Behav 2021;114:106524. Crossref