East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2024;34:103-8 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2431

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Abstract

Background: Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and COVID-19 are both highly infectious diseases that cause severe respiratory illness. This study aimed to compare survivors of SARS and COVID-19 and identify factors associated with long-term psychiatric comorbidities.

Methods: This was a retrospective cohort study of adult Chinese survivors of SARS and COVID-19 who had been admitted to the United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong. In total, 90 SARS survivors and 60 COVID-19 survivors agreed to participate, and their data at 30 months post-infection were retrieved.

Results: Compared with SARS survivors, COVID-19 survivors had a lower prevalence of psychiatric disorder at 30 months post-infection (6.7% vs 33.3%, p <0.001). Higher levels of anxiety and depression were independently associated with greater perceived functional impairment, higher average pain intensity level in the past month, and less use of rational problem solving.

Conclusion: Experience of SARS might be a protective factor to combat COVID-19 in the Hong Kong population. Potential treatment strategies include optimisation of pain management, physical rehabilitation, and enhancing effective coping strategies.

Mimi MC Wong, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

SH Tsoi, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Nora BW Lai, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, The Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

YL Wong, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

KW Yip, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

YY Fung, Specialist Out-patient Department, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Eugene YK Tso, Department of Medicine & Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Ivan WC Mak, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

CM Chu, Department of Medicine & Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

PF Pang, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Address for correspondence: Dr Mimi MC Wong, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: wmc009@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 8 July 2024; Accepted: 10 September 2024

Both severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and COVID-19 are highly infectious diseases that cause severe respiratory illness. The SARS epidemic spread to 29 countries, infected 8096 people, and resulted in 774 deaths and a mortality rate of 9.2%.1 In Hong Kong, 1755 people were infected and nearly 300 died.2 The COVID-19 pandemic spread much faster globally. Only 4 months after the first recorded case in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, there were over 118 000 cases and 4291 deaths across 114 countries.3,4 By June 2024, there had been over 775 million cases and 7 million deaths worldwide.5 In Hong Kong, over 3 million people were infected and approximately 13 825 people died6 out of a population of approximately 740 million.7

In Hong Kong, the SARS epidemic was quickly curbed within 3 months after its outbreak in March 2003,8 whereas the COVID-19 pandemic lasted for 3 years. Hong Kong had been successful in containing the Alpha and Delta variants,9 but the fifth wave caused by the Omicron variant resulted in over 9000 deaths 10 with >70% among those aged ≥80 years.9 The pandemic gradually subsided with enhanced population immunity secondary to immunisation, natural infection, and hybrid immunity.11 In March 2023, the Hong Kong government lifted all infection control measures. In 2020, the unemployment rates surged to a 16-year high of 6.6%.12 The pandemic and strict control measures (such as universal masking, social distancing, isolation of confirmed cases, and quarantine of contacts in healthcare facilities) had unfavourable socioeconomic effects.13

Regarding clinical presentations and long-term outcomes, patients with SARS usually have a dry cough 2 to 7 days post-infection and subsequently develop pneumonia.14 On the contrary, 4% to 41% of patients with COVID-19 are asymptomatic,15 whereas others had mostly flu-like symptoms and occasionally loss of taste or smell. Both SARS and COVID-19 affect respiratory, cardiac, haematological, gastrointestinal, and neurological systems. Acute respiratory distress syndrome is the most common sequela and cause of death among both patients.16 Severe sequelae of SARS include pulmonary fibrosis and femoral head necrosis as a result of large doses of steroid pulse therapy.17 ‘Long COVID’ was estimated to occur in at least 10% of those infected, with symptoms of cough, dyspnoea, palpitations, fatigue, memory loss, cognitive impairment, and disordered sleep,18 whereas ‘long SARS’ was coined to describe fatigue, respiratory symptoms, impaired cognition, and sleep disturbances post-SARS.19

Regarding psychiatric comorbidities, during the post- SARS period, the point prevalence was 32.2% for post- traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 14.9% for depression, and 14.8% for anxiety disorder.20 In Hong Kong, PTSD was the most prevalent long-term psychiatric condition, followed by depressive disorders.21 During the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall prevalence was 23.9% for depression symptoms, 23.4% for anxiety symptoms, 14.2% for stress, 16.0% for distress, 26.5% for insomnia symptoms, 24.9% for post-traumatic stress symptoms, and 19.9% for poor mental health. Both the SARS and COVID-19 outbreaks led to similar prevalences of depression, features of anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and poor mental health.22

A population-based study in Hong Kong showed that people who were not affected by SARS in 2003 had poorer mental health status during the COVID-19 pandemic. This suggests that those who were affected by SARS might have been more resilient or psychologically prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic.23 Therefore, this study aimed to compare survivors of SARS and COVID-19 and identify factors associated with long-term psychiatric comorbidities.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of adult Chinese survivors of SARS and COVID-19 who had been admitted to the United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong. Of 119 survivors of SARS, 90 were eligible and agreed to participate, and their data at 30 months post-infection were retrieved.21 We also recruited 42 survivors of COVID-19 who attended the post-COVID-19 clinic of our hospital between September 2022 and November 2023, as well as 18 survivors of COVID-19 who were recalled for interview at 30 months post-infection.

Participants’ sociodemographic and biopsychosocial data were collected. The Chinese version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV was administered by psychiatrists to ascertain major Axis I DSM-IV diagnoses of participants.24 The Multidimensional Health Locus of Control scales25 were used to assess the degree to which participants attributed the influences of themselves, others, and chance on their health and illness.26 The Chinese Ways of Coping Questionnaire was used to indicate which coping activities participants used to deal with the events of daily life.27 Within this, ‘rational problem solving’ and ‘seeking support and ventilation’ are regarded as the active problem-focused categories, whereas ‘resigned distancing’ and ‘passive wishful thinking’ are regarded as avoidance categories. The Post-COVID-19 Functional Status scale was used as a patient-report tool to evaluate the consequences of COVID-19 and their effect on functional status.28 The Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) was used to assess the distress level. It comprises the domains of intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal to parallel the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD.29 A score of 2 in each subscale was the cut-off point to indicate a moderate level of distress. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to assess both anxiety and depression levels. It consists of two independent subscales for anxiety and depression.30

A score of 11 in respective subscales was the cut-off point to indicate a moderate level of anxiety or depression.31

Results

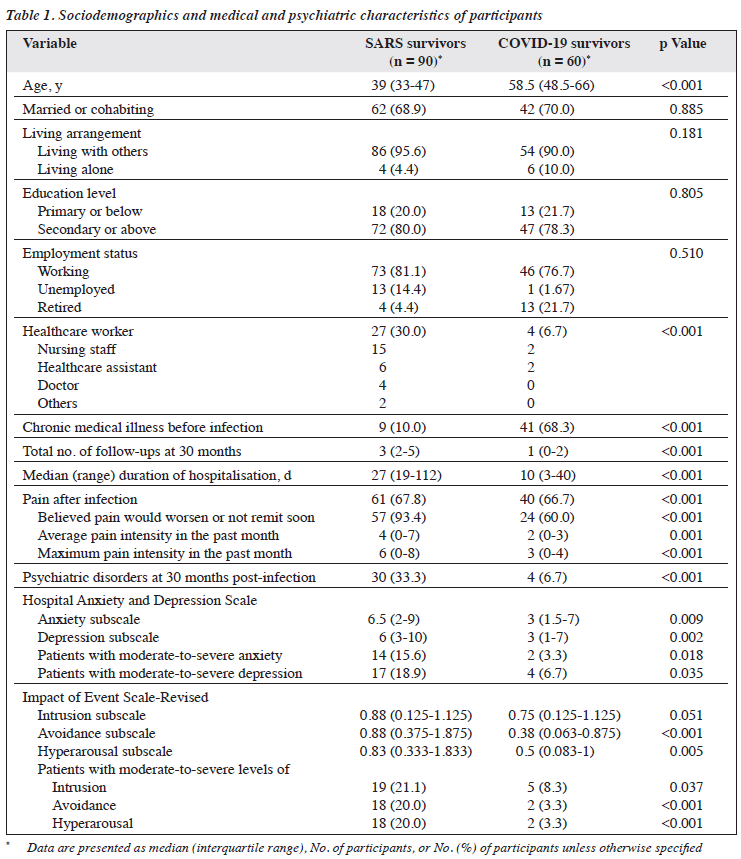

In total, 52 female and 38 male survivors of SARS and 32 female and 28 male survivors of COVID-19 were included in the analysis. COVID-19 survivors were older than SARS survivors (58.5 vs 39.0 years, p < 0.001, Table 1), with a higher proportion of those aged ≥65 years (31.7% vs 5.6%, p < 0.001). A higher proportion of SARS survivors were healthcare workers (30.0% vs 6.7%, p < 0.001). A higher proportion of COVID-19 survivors had chronic medical illnesses before infection (68.3% vs 10%, p < 0.001). However, at 30 months after hospitalisation, SARS survivors had more follow-up visits (median: 3 vs 1, p < 0.001) and longer duration of hospitalisation (median: 27 vs 10 days, p < 0.001). In both groups, approximately two- thirds of participants had distressing pain after infection. SARS survivors reported higher average (median: 4 vs 2, p = 0.001) and maximum (median: 6 vs 3, p < 0.001) pain intensity levels in the past month. A higher proportion of SARS survivors who reported pain believed that their pain would worsen or not remit soon (93.4% vs 60.0%, p<0.001).

Before infection, among 90 SARS survivors, five were retrospectively diagnosed with depressive disorder and one with alcohol dependence, whereas among 60 COVID-19 survivors, one was diagnosed with depressive disorder and one with adjustment disorder. At 30 months post-infection, a higher proportion of SARS survivors had psychiatric disorders (33.3% vs 6.7%, p < 0.001). The most common diagnoses were PTSD (n = 23) and depressive disorders (n = 12) among SARS survivors, whereas only four COVID-19 survivors had psychiatric disorders (two with generalised anxiety disorder, one with depressive disorder, and one with panic disorder). The pattern of psychiatric disorders differed significantly between groups (p < 0.001).

SARS survivors had higher HADS median subscale scores for anxiety (6.5 vs 3, p = 0.009) and depression (6 vs 3, p = 0.002), with a higher proportion having moderate- to-severe levels of anxiety (15.6% vs 3.3%, p = 0.018) or depression (18.9% vs 6.7%, p = 0.035) at 30 months post- infection. COVID-19 survivors had lower IES-R median subscale scores for avoidance (0.38 vs 0.88, p < 0.001) and hyperarousal (0.5 vs 0.83, p = 0.005), with a lower proportion having moderate-to-severe levels of intrusion (8.3% vs 21.1%, p = 0.037), avoidance (3.3% vs 20.0%, p < 0.001), and hyperarousal (3.3% vs 20.0%, p < 0.001) at 30 months post-infection.

Among COVID-19 survivors, none had been infected with SARS, whereas two had family members and three had friends died of SARS. Using a five-point Likert scale, COVID-19 survivors perceived SARS to be more deadly than COVID-19 (median: 4 vs 3, p < 0.001). They found their experience living through the SARS endemic was helpful in dealing with COVID-19, with a median rating of 3. They also believed that their experience with SARS helped to increase their alertness to COVID-19 symptoms, personal hygiene, and appreciation of the importance of personal protective equipment. 88.3% perceived their emotional support was enough; 26.7% worried that COVID-19 would lead to death. SARS survivors had higher stigmatisation rating (median: 3 vs 1, p = 0.002), with a higher proportion having experienced serious to very serious stigma after discharge (47.5% vs 25%, p = 0.005).

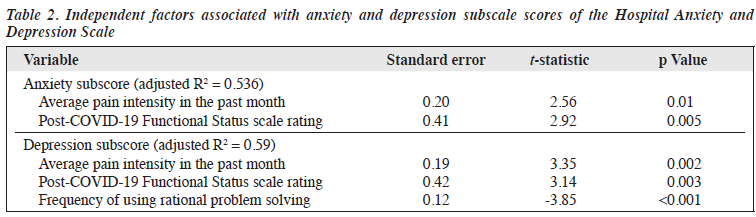

In the univariate analysis, higher HAD subscale scores for anxiety or depression were associated with higher average and maximum pain intensity levels in the past month, greater perceived functional impairment, higher perceived inadequacy of social support, more symptoms during and after COVID-19, more follow-up visits after COVID-19, higher perceived dangerousness of COVID-19, more use of resigned distancing and passive wishful thinking and less use of rational problem solving, and weaker belief that health status is linked to own actions and stronger belief that health status is linked to nothing in particular.

In the multiple linear regression analysis, higher HADS subscale score for anxiety was independently associated with greater perceived functional impairment and higher average pain intensity level in the past month, whereas higher HAD subscale score for depression was independently associated with greater perceived functional impairment, higher average pain intensity level in the past month, and less use of rational problem solving (Table 2).

Discussion

COVID-19 survivors had lower prevalence of psychiatric disorders at 30 months post-infection, and none had PTSD. This can be explained by the findings that SARS survivors had a longer hospital stay, more complications requiring more follow-up visits, a higher level of chronic pain, and more stigmatisation associated with infection. The overall case fatality rate was higher for SARS than for COVID-19 (14%-15% vs 2%).16,32 Among patients with SARS, 50% to 85% needed oxygen supplementation, and there were more steroid-associated complications.16 The proportion of deaths among the younger population and healthcare workers was also higher for SARS; this caused panic and despair.16 Inflammatory cytokines and the presence of ACE-2 receptors on the cell surface are common pathophysiological mechanisms between COVID-19 and depression.33 Similarly, SARS patients with severe symptoms had a positive correlation between the presence of immunoglobulin G antibodies against the virus and the occurrence of psychiatric diseases such as depression.34 Mood-related disorders are multifactorial diseases, and various factors can cause their onset and maintenance. The isolation and hospitalisation periods as well as the fear of death can also cause stress.

Those who survived COVID-19 are at risk of psychiatric sequelae, but symptoms generally improve over time.35 COVID-19 has significantly lower odds of leading to anxiety disorder (odds ratio = 0.55, p = 0.01) than other respiratory infections. COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk of psychiatric sequelae within 3 months of infection but has a lower risk of developing new psychiatric sequelae 4 to 6 months after infection.36 Among individuals diagnosed with COVID-19, the increased incidence of mood and anxiety disorders is transient, with no overall excess, compared with other respiratory infections. The risk of common psychiatric disorders returns to baseline after 1 to 2 months; the incidence is equal to that of the matched group (mood disorders at 457 days, anxiety disorders at 417 days).37

The prevalence of PTSD related to the COVID-19 pandemic varies greatly from 8% to 50%; this suggests that the local context affects psychological responses.38 In Hong Kong, the prevalence of PTSD symptoms is generally lower 1 year after the pandemic began, compared with the early stages of the pandemic.39 This may reflect that people have learned to cope with the impacts of the pandemic, or that they have become increasingly insensitive to its volatility. In Hong Kong, 12.4% of participants scored ≥33 on the IES-R, which indicates possible PTSD, 1 year after the start of the pandemic,39 compared with the 28.6% soon after the first community outbreak occurred.40 As the pandemic worsens, people have learned to cope better. In our study, only 6.7% of COVID-19 survivors had an IES-R score of ≥33 at 30 months post-infection. Previous experience of SARS might be a protective factor.23 The development of vaccines and antiviral drugs, effective Chinese medicine for symptom relief, and availability of isolation facilities all help to allay fear among the people of Hong Kong.41 Most people either experience no significant decline in their mental health or have a recovery of mental health with the progression of time; only 5% to 10% show long-term distress.39

In our study, anxiety and depression were associated with pain level, functional impairment, and rational problem solving. A high incidence of non-localised chronic pain syndromes is reported in the post-COVID-19 period.42 Post-COVID chronic pain may be construed as a newly developed chronic pain associated with post-viral syndrome or worsening of pre-existing chronic pain. Therefore, patients with chronic pain should receive effective treatment according to their specific needs. Mild-to-moderate pain associated with post-COVID symptoms can be relieved with simple analgesics. For patients with moderate-to- severe pain, opioids with minimal immune-suppression effects are recommended. For neuropathic pain symptoms, gabapentinoids are suitable options.42

Clinicians could consider factors identified in this study (ie, having significant pain and functional disability) to help detect hidden psychiatric disorders in patients with previous infection. Functional impairment could be a result of depressed mood, as low mood plays a predominant role in activating both anxiety symptoms and functional impairment.43 Potential treatment strategies include optimisation of pain management, physical rehabilitation, and enhancing effective coping strategies. Problem-solving therapy (ie, learning the skills to find solutions to their problems in an objective way) is effective for managing depression.44

There were limitations to the study. First, the sample size was small, especially for the COVID-19 group, which may have limited the statistical power. Only 60 COVID-19 survivors were recruited out of the 3 million people infected in Hong Kong; all contracted COVID-19 during the first to fourth waves when inpatient treatment was arranged. Second, there was no matching of the participants. Those in the COVID-19 group were older than those in the SARS group. At 30 months post-infection, many patients did not require follow-up; younger patients who were working declined to come back for interview, whereas those who were retired were willing to return for interview. Third, discrimination and stigmatisation of patients with COVID-19 might have resulted in under-reporting of their psychopathology to avoid ‘double stigmatisation’. However, the investigators were not involved in the clinical care of the patients; this may have ameliorated the issue of under-reporting. Fourth, participants were recruited from a single hospital, and the results are therefore not generalisable to all patients with COVID-19 in Hong Kong. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital beds were allocated centrally rather than according to the catchment area. Therefore, our sample was representative of the entire Hong Kong population.

Conclusion

Compared with SARS survivors, COVID-19 survivors had a lower prevalence of psychiatric disorders at 30 months post-infection (6.7% vs 33.3%). Higher levels of anxiety and depression were independently associated with greater perceived functional impairment, higher average pain intensity level in the past month, and less use of rational problem solving. Potential treatment strategies include optimisation of pain management, physical rehabilitation, and enhancing effective coping strategies.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Kowloon Central / Kowloon East Cluster Research Ethics Committee (reference: KC/ KE-22-0122/ER-3). The participants provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Yiu Gar Chung, Michael, Dr Cheung Pik Shan, Dr Chan Shut Wah, Kenneth, Ms Sammi Ho, and staff of the post-COVID-19 clinic and Department of Psychiatry in the United Christian Hospital.

References

- World Health Organization. Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003-24 July 2015. Accessed 8 July 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/ publications/m/item/summary-of-probable-sars-cases-with-onset-of- illness-from-1-november-2002-to-31-july-2003.

- Shung ECCW. Data cleaning, maintenance, and analysis of the HA SARS Collaborative Groups database. Hong Kong Med J 2008;14(Suppl 1):S11-3.

- Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed 2020;91:157-60.

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Accessed 8 July 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/director- general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at- the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 deaths | WHO COVID-19 dashboard. Accessed 8 July 2024. Available from: https://data.who.int/ dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=o

- Real-time dashboard. Coronavirus disease 2019. 2020. Accessed 8 July 2024. Available from: https://covid19.sph.hku.hk/

- Census and Statistics Department. Population and Household Statistics Analysed by District Council District. Accessed 8 July 2024. Available from: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/wbr.html?ecode=B1130301202 3AN23&scode=150.

- Zhong NS, Wong GW. Epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): adults and children. Paediatr Respir Rev 2004;5:270-4.

- Cheung PH, Chan CP, Jin DY. Lessons learned from the fifth wave of COVID-19 in Hong Kong in early 2022. Emerg Microbes Infect 2022;11:1072-8.

- Centre for Health Protection. Statistics on 5th wave of COVID-19. Accessed 8 July 2024. Available from: https://www.covidvaccine.gov. hk/pdf/5th_wave_statistics.20230727.pdf.

- Del Rio C, Malani PN. COVID-19 in 2022 - the beginning of the end or the end of the beginning? JAMA 2022;327:2389-90.

- Hong Kong Monetary Authority. Economic and Financial Environment. Accessed 8 July 2024. Available from: https://www.hkma.gov. hk/media/eng/publication-and-research/annual-report/2020/12_ Economic_and_Financial_Environment.pdf.

- Wong SC, Au AKW, Lo JYC, et al. Evolution and control of COVID- 19 epidemic in Hong Kong. Viruses 2022;14:2519.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. SARS Basics Fact Sheet. Accessed June 5 2022. Available from: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_ cdc_gov/sars/about/fs-sars.html.

- Byambasuren O, Cardona M, Bell K, Clark J, McLaws ML, Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Assoc Med Microbiol Infect Dis Can 2020;5:223-34.

- Keshta AS, Mallah SI, Al Zubaidi K, et al. COVID-19 versus SARS: a comparative review. J Infect Public Health 2021;14:967-77.

- Zhang P, Li J, Liu H, et al. Long-term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital-acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: a 15-year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Res 2020;8:8.

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023;21:133-46.

- Patcai J. Is ‘Long Covid’ similar to ‘Long SARS’?. Oxf Open Immunol 2022;3:iqac002.

- Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID- 19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:611-27.

- Mak IW, Chu CM, Pan PC, Yiu MG, Chan VL. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:318-26.

- Zhao YJ, Jin Y, Rao WW, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities during the SARS and COVID-19 epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Affect Disord 2021;287:145-57.

- Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3740.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, William JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002.

- Wallston KA, Wallston BS, DeVellis R. Development of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) Scales. Health Educ Monogr 1978;6:160-70.

- Au A, Li P, Chan J, et al. Predicting the quality of life in Hong Kong Chinese adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2002;3:350-7.

- Chan DW. The Chinese Ways of Coping Questionnaire: assessing coping in secondary school teachers and students in Hong Kong. Psychol Assess 1994;6:108-16.

- Klok FA, Boon GJAM, Barco S, et al. The post-COVID-19 functional status scale: a tool to measure functional status over time after COVID-19. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2001494.

- Wu KK, Chan KS. The development of the Chinese version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised (CIES-R). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38:94-8.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361-70.

- Leung CM, Ho S, Kan CS, Hung CH, Chen CN. Evaluation of the Chinese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. A cross-cultural perspective. Int J Psychosom 1993;40:29-34.

- Pormohammad A, Ghorbani S, Khatami A, et al. Comparison of confirmed COVID-19 with SARS and MERS cases — clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, radiographic signs and outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol 2020;30:e2112.

- da Silva Lopes L, Silva RO, de Sousa Lima G, de Araújo Costa AC, Barros DF, Silva-Néto RP. Is there a common pathophysiological mechanism between COVID-19 and depression? Acta Neurol Belg 2021;121:1117-22.

- Severance EG, Dickerson FB, Yolken RH. Autoimmune phenotypes in schizophrenia reveal novel treatment targets. Pharmacol Ther 2018;189:184-98.

- Schou TM, Joca S, Wegener G, Bay-Richter C. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19: a systematic review. Brain Behav Immun 2021;97:328-48.

- Murata F, Maeda M, Ishiguro C, Fukuda H. Acute and delayed psychiatric sequelae among patients hospitalised with COVID-19: a cohort study using LIFE study data. Gen Psychiatr 2022;35:e100802.

- Taquet M, Sillett R, Zhu L, et al. Neurological and psychiatric risk trajectories after SARS-CoV-2 infection: an analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies including 1 284 437 patients. Lancet Psychiatry 2022;9:815-27.

- Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2021;295:113599.

- Cao Y, Siu JY, Shek DTL, Shum DHK. COVID-19 one year on: identification of at-risk groups for psychological trauma and poor health-protective behaviour using a telephone survey. BMC Psychiatry 2022;22:252.

- Lau BHP, Chan CLW, Ng SM. Resilience of Hong Kong people in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from a survey at the peak of the pandemic in Spring 2020. Asia Pac J Soc Work Dev 2020;31:105-14.

- Cheung YYH, Lau EHY, Yin G, Lin Y, Cowling BJ, Lam KF. Effectiveness of vaccines and antiviral drugs in preventing severe and fatal COVID-19, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis 2024;30:70-8.

- El-Tallawy SN, Perglozzi JV, Ahmed RS, et al. Pain management in the post-COVID era - an update: a narrative review. Pain Ther 2023;12:423-48.

- Zhou J, Zhou J, Feng L, et al. The associations between depressive symptoms, functional impairment, and quality of life, in patients with major depression: undirected and Bayesian network analyses. Psychol Med 2022;53:1-13.

- Cuijpers P, de Wit L, Kleiboer A, Karyotaki E, Ebert DD. Problem- solving therapy for adult depression: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2018:48-27-37/