East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2023;33:107-13 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2336

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Abstract

Background: Asthma is a common respiratory disease in children. Family factors play a role in its incidence and severity. This study investigated the effect of parental psychological flexibility, parental psychological adjustment to the child’s illness, and parental psychological distress on the severity of asthma symptoms of children through mediating child anxiety.

Methods: A total of 216 parents of children with asthma were asked to complete the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire, the Parent Experience of Child Illness, the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale - 21 Items, and the parent-report Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. Severity of asthma symptoms was assessed by spirometry.

Results: The highest path coefficient was between parental psychological flexibility and the severity of paediatric asthma symptoms (β = 0.34). Parental psychological distress was found to affect the severity of asthma symptoms of children (β = -0.21) and also mediate child anxiety and then affect the severity of asthma symptoms of children (β = -0.25).

Conclusion: Parental psychological flexibility, parental psychological adjustment to the child’s illness, and parental psychological distress had significant effects on the severity of asthma symptoms of children through mediating child anxiety.

Mehri Parvane, Department of Psychology, Lorestan University, Khoramabad, Iran

Fatemeh Rezaei, Department of Psychology, Lorestan University, Khoramabad, Iran

Address for correspondence: Dr Fatemeh Rezaei, Department of Psychology, Lorestan University, Khoramabad, Iran. Email: rezaei.f@lu.ac.ir

Submitted: 5 July 2023; Accepted: 24 November 2023

Introduction

Asthma affects 36% of children and adolescents worldwide; it is the most common chronic health problem among this group and can be lifelong.1 In the United States, the prevalence of asthma was 8.9% in 2018.2 Asthma causes chronic inflammation of the lower airways and bronchoconstriction, with chest tightness, wheezing, and coughing being the main symptoms.3

Psychological factors can lead to the development, exacerbation, and improvement of asthma. Family is the closest and most intimate system for a child and, therefore, two-way communication plays an important role in understanding the psychological processes that affect the health of children with asthma.4

Parental psychological flexibility involves parenting and bringing up children and is associated with the prevalence of paediatric asthma. It is the ability to endure unpleasant experiences and private events, fully and consciously, with acceptance-based coping strategies.5 Emotional suppression and avoidance coping plans have paradoxical effects.6 Improving parental psychological flexibility significantly reduces the symptoms of asthma in children.7 When negative emotions arise while caring for a child with asthma, parents who are less psychologically flexible may try to respond to their problems through experimental avoidance, which can have a negative impact on the child’s symptoms.7 Low levels of parental psychological flexibility cause anxiety, depression, chronic pain, and negative psychological symptoms in children with asthma.8

Inhaled corticosteroid is a long-term treatment for asthma, but many parents are concerned about its adverse effects such as growth disorder.9 Therefore, these parents may have poor flexibility regarding the use of medications and thus exacerbate asthma symptoms in their children. Parents also often fear that their child will die from recurrent asthma attacks.10 Caregivers of children with asthma suffer more physiologic stress, psychological stress, intellectual stress, anxiety, and depression than parents of healthy children.11 Parental psychological distress is a contributor to poor asthma control in children.7 Parental anxiety and depression can reduce their sense of responsibility for caring, educating, and feeding their children.

Parents play the most important role in supporting their children, but they can also transfer their anxiety to them. Children whose parents have mental health problems are more likely to exhibit mental disorders.12 Children with asthma whose parents have a high level of psychological distress (including anxiety, depression, and stress) have more asthma symptoms, use more oral corticosteroids and emergency care services, and have more hospital admissions due to asthma attacks.13

Parents who are not psychologically adjusted to their child’s asthma cannot manage the disease well. Adjustment to a child’s chronic disease is a continuous process that parents face at every stage of the diagnosis-treatment process. Eventually, these parents experience psychological problems that affect asthma management behaviours.14

Theories of anxiety development during childhood postulate that parental characteristics such as overprotection, control, criticism, and rejection are associated with anxiety symptoms in their children.15 Parents of children with chronic conditions may inadvertently pass on their anxiety to their child, especially if their child is already anxious. One in five children with asthma has an anxiety disorder; the rate is three times that of healthy children.16 Children with asthma who have anxiety experience more severe asthma symptoms than those without anxiety, resulting in decreased physical and emotional functioning and increased utilisation of emergency services.17

Identifying these psychological factors in parents helps to improve the symptoms and psychological condition of their children. Acceptance commitment therapy helps to improve the health and relationships of parents and their children by strengthening parental flexibility.7 Mindfulness activities, such as yoga, reduce heart rate and blood pressure and increase feelings of happiness and relaxation in children with asthma.18

We developed a conceptual model to investigate associations between exogenous, mediating, and endogenous variables based on three hypotheses: (1) parental psychological flexibility contributes to the development of asthma symptoms in children through mediating child anxiety; (2) parental psychological adjustment contributes to the development of asthma symptoms in children through mediating child anxiety; and (3) parental psychological distress contributes to the development of asthma symptoms in children through mediating child anxiety.

Methods

Parents of children aged 7 to 16 years diagnosed with asthma who were referred to the Asthma and Allergy Clinic of the Shahid Rahimi Hospital in Khorramabad between 2019 and 2020 were invited to participate using convenience sampling. Children or parents who had a diagnosis of mental disorders or chronic physical problems were excluded.

Parents were asked to complete the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II (AAQ-II),19 the Parent Experience of Child Illness (PECI),20 the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 Items (DASS-21),21 and the parent-report version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS).22

Parental psychological flexibility was assessed using the AAQ-II, which consists of seven questions that measure reluctance to experience unwanted thoughts and feelings and the inability to pay attention to inner values using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true). Total scores range from 7 to 49; higher scores indicate higher psychological inflexibility; a cut-off score of ≥25 indicates psychological inflexibility. Its test-retest reliability is 0.81 and its internal consistency is 0.84.19

Parental psychological adjustment in the care of a child with asthma was assessed using the PECI, which consists of 25 items in four subscales: guilt and worry, unresolved sorrow and anger, long-term uncertainty, and emotional resources.20 Each item is measured using a five- point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Its internal reliability varies from 0.72 to 0.89, and its Cronbach’s alphas for the four subscales range from 0.67 to 0.87.

Parental psychological distress was assessed using DASS-21, which comprises 21 items that assess depression, anxiety, and stress using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. Cut-off scores for extreme severity in the respective subscales are 28, 20, and 34; higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. The Cronbach’s alphas for depression, anxiety and stress subscales are 0.82, 0.88, and 0.90, respectively.21

Child anxiety was assessed using the parent-report SCAS, which consists of 38 items measured on a four- point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always).22 Maximum score is 114; a percentile score of ≥85% suggests elevated anxiety.

The severity of asthma symptoms was assessed using a spirometer. According to the Australian National Asthma Campaign, symptoms of asthma include wheezing and shortness of breath during walking and at night. Pulmonary function is categorised as mild, moderate, or severe based on the percentage of the predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).23 In mild asthma, symptoms occur sometimes but not during walking or at night; medications are used less than twice a week, and the FEV1 is >80%. In moderate asthma, symptoms occur most of the time but less than once a week during walking or at night; medications are used often, and the FEV1 is between 60% and 80%. In severe asthma, symptoms occur every day and more than once a week during walking or at night; medications are taken >3 times a week, and the FEV1 is <60%.

The Pearson’s correlation test was used to determine associations between variables. Owing to the existence of latent variables and their indirect effects, the three hypotheses were investigated using structural equation modelling. Mediation effect was determined using the bootstrapping method. According to criteria set out by Kline,24 the goodness of fit was determined by indices of Chi-squared divided by degrees of freedom (CMIN/df), comparative fit index (CFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). The model is deemed fit when the CMIN/df is ≤3.0, CFI is ≥0.95, GFI is ≥0.95, NFI is ≥0.95, TLI is ≥0.95, and RMSEA is ≤0.08.

Results

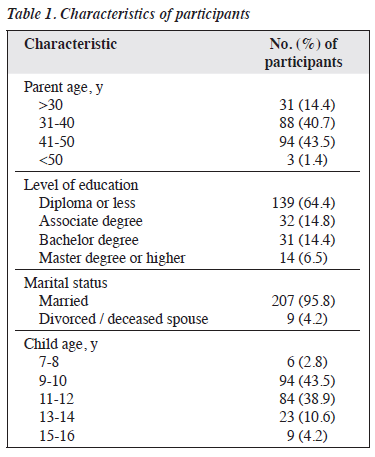

Of the 280 children with asthma selected, 22 were excluded because of mental disorders such as depression, intellectual disability, and chronic physical disorders; a further 42 were excluded because of their parents having mental disorders or chronic physical problems. The remaining 216 children (75 boys and 141 girls) and their parents (67 males and 149 females) were included in the analysis (Table 1).

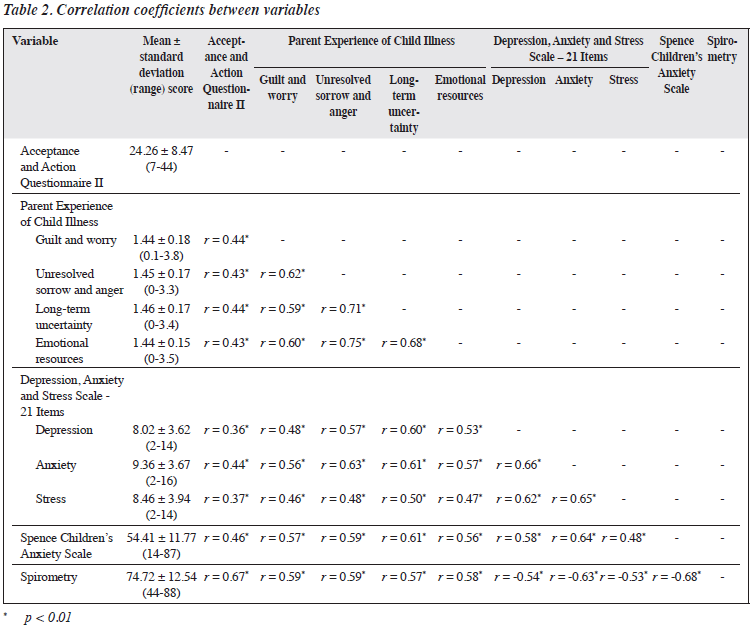

The mean AAQ-II score for parental psychological flexibility was 24.26. The mean DASS-21 subscale scores for parental stress, depression, and anxiety were 8.46, 8.02, and 9.36, respectively (mild). The mean PECI for parental psychological adjustment to the child’s illness was 1.44. The mean SCAS score for child anxiety was 54.41 (moderate). The mean severity of asthma symptoms of children was 74.72 (moderate) [Table 2].

Correlations between variables were all significant (p < 0.01) and ranged from 0.36 (between parental psychological flexibility and parental depression) to 0.75 (between PECI subscales of unresolved sorrow and anger and long-term uncertainty) [Table 2].

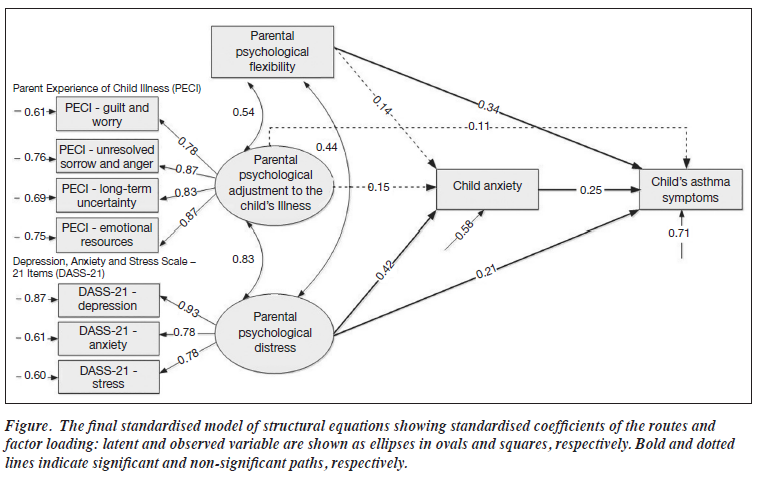

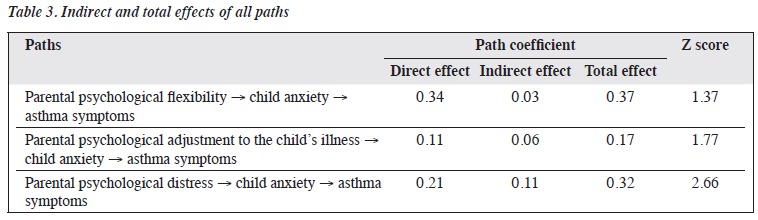

The proposed model demonstrated good fit, with CMIN/df = 1.13 (χ2 = 30.649, p = 0.001), CFI = 0.99, GFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.99, and RMSEA = 0.029 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.312-0.991). It explained 58% of the variance of child anxiety and 71% of the variance of asthma symptoms (Figure). Correlation was highest between parental psychological flexibility and severity of paediatric asthma symptoms (β = 0.34, 95% CI = 0.27-0.15, p = 0.01). Parental psychological distress contributed to severity of paediatric asthma symptoms (β = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.61-0.07, p = 0.01).

Parental psychological flexibility contributed to child anxiety (β = -0.21, construct reliability [CR] = 3.05, p = 0.002) and parental anxiety about asthma symptoms (β = -0.25, CR = 3.73, p < 0.001). The indirect coefficient was 0.05 (0.21 × 0.25), and this hypothesis was rejected.

Parental psychological adjustment contributed to child anxiety (β = -0.15, CR = 2.43, p = 0.015) and parental anxiety about asthma symptoms (β = 0.25, CR = 3.73, p = 0.001). The indirect coefficient was 0.03 (0.23 × 0.25), and this hypothesis was rejected.

Parental psychological distress contributed to child anxiety (β = 0.42, CR = 3.80, p = 0.001) and parental anxiety about asthma symptoms (β = 0.25, CR = 3.73, p = 0.001). The indirect coefficient was 0.11 (0.42 × 0.25). This hypothesis was confirmed because 95% of the lower (0.022) and upper (0.242) limits were of equal sign and did not include 0 (Table 3).

Discussion

Parental psychological flexibility had a direct and significant effect on the severity of asthma symptoms in children, consistent with the findings of a study.7 Flexible parents who are aware of and accept their own care experience are more likely to look for opportunities to improve their management behaviours for their child’s asthma rather than avoiding problems. Parental psychological flexibility makes children more flexible. When parents are less avoidant of their children’s asthma, the child will become more flexible in responding to health problems and eventually take a role in actively managing their asthma symptoms with parents.

Parental psychological distress (anxiety, stress, and depression) had a direct and significant effect on the severity of asthma symptoms in children, consistent with the results of two studies.25,26 When parents have depression, anxiety, stress, or chronic anger, the child’s physical health may be affected. The psychological health and characteristics of parents are associated with longitudinal changes in inflammatory markers in children with asthma.25 Higher levels of perceived parental stress are associated with increased interleukin-4, and parental depression is associated with increased eosinophil cationic protein.25 These findings suggest that parents may transfer stress or depression to their children and result in allergic reactions in children.25 Parents who are less aware (because of stress or depression) are more likely to allow their children with asthma to be exposed to cigarette smoke, viruses, or other asthma triggers.27 Moreover, depressed parents may forget to administer inhaled corticosteroids to their children.28

Child anxiety had a direct and significant effect on the severity of asthma symptoms in children, consistent with results of a study.29 This is of relevance because the severity of anxiety is moderate in people with asthma; anxiety and depression are associated with poor asthma control; and improving anxiety is almost four times more effective in controlling asthma than improving depression.30

Parental psychological distress had an indirect and significant effect on the severity of asthma symptoms in children through mediating child anxiety. However, association between parental anxiety and child anxiety is complex. Different levels of parental depression, anxiety, and worry are associated with child anxiety. Examining parental anxiety and depression is important because children can learn anxiety and stress from their parents, depending on their developmental stage. Children with asthma who also have stress and anxiety tend to have more asthma symptoms.

Parental psychological adjustment to the child’s illness did not contribute to asthma symptoms of children or child anxiety. One reason for rejecting this hypothesis may be related to the characteristics of the sample, because we included the parents of children with asthma in an outpatient clinic; association may be higher in inpatient settings.

The present study had limitations. Most parents referred to the clinic were mothers and therefore the results may be biased. Self-report questionnaires were used to measure parental psychological distress, parental psychological flexibility, parental psychological adjustment to the child’s illness, and parent-report child anxiety, but interviews by researchers would be more objective. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, convenience sampling, rather than random sampling, was used. The sample was selected from a charitable clinic and thus the socioeconomic status of most families was low. It would be more representative if the sample included a wider variety of socioeconomic backgrounds. Other variables such as types of medicine used to treat the asthma, psychological status of parents, and levels of parental awareness of asthma should have been included in the analysis.

Conclusion

Parental psychological flexibility, parental psychological adjustment to the child’s illness, and parental psychological distress affect child anxiety in children with asthma.

Attention should be paid to the mental health of parents who have children with asthma in order to improve their children’s respiratory condition. Children’s asthma symptoms can be positively affected by strengthening parental psychological flexibility and reducing parental psychological distress.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences (reference: IR.LUMS. REC.1398.065). The patients were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

References

- Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G. Worldwide asthma epidemiology: insights from the Global Health Data Exchange database. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2020;10:75-80. Crossref

- Liu W, Wei J, Cai M, et al. Particulate matter pollution and asthma mortality in China: a nationwide time-stratified case-crossover study from 2015 to 2020. Chemosphere 2022;308:136316. Crossref

- Saglani S, Menzie-Gow AN. Approaches to asthma diagnosis in children and adults. Front Pediatr 2019;7:148. Crossref

- Srour-Alphonse P, Cvetkovski B, Azzi E, et al. Understanding the influences behind parents’ asthma decision-making: a qualitative exploration of the asthma network of parents with children with asthma. Pulm Ther 2021;7:151-70. Crossref

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: the Process and Practice of Mindful Change. Guilford Press; 2011.

- Flujas-Contreras JM, García-Palacios A, Gómez I. Parenting intervention for psychological flexibility and emotion regulation: clinical protocol and an evidence-based case study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:5014. Crossref

- Chong YY, Mak YW, Loke AY. The role of parental psychological flexibility in childhood asthma management: an analysis of cross- lagged panel models. J Psychosom Res 2020;137:110208. Crossref

- Stotts AL, Villarreal YR, Klawans MR, et al. Psychological flexibility and depression in new mothers of medically vulnerable infants: a mediational analysis. Matern Child Health J 2019;23:821-9. Crossref

- Said ASA, Hussain N, Abdelaty LN, Al Haddad AH, Mellal AA. Inhaled corticosteroid phobia among parents of Egyptian asthmatic children. Clin Epidemiol Global Health 2021;12:100810. Crossref

- Goddard BMM, Hutton A, Guilhermino M, McDonald VM. Parents’ decision making during their child’s asthma attack: qualitative systematic review. J Asthma Allergy 2022;15:1021-33. Crossref

- Foronda CL, Kelley CN, Nadeau C, et al. Psychological and socioeconomic burdens faced by family caregivers of children with asthma: an integrative review. J Pediatr Health Care 2020;34:366-76. Crossref

- Wiegand-Grefe S, Sell M, Filter B, Plass-Christl A. Family functioning and psychological health of children with mentally ill parents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:1278. Crossref

- Bartlett SJ, Kolodner K, Butz AM, Eggleston P, Malveaux FJ, Rand CS. Maternal depressive symptoms and emergency department use among inner-city children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:347-53. Crossref

- Chong YY, Mak YW, Loke AY. Psychological flexibility in parents of children with asthma: analysis using a structural equation model. J Child Fam Stud 2017;26:2610-22. Crossref

- Allen JL, Sandberg S, Chhoa CY, Fearn T, Rapee RM. Parent- dependent stressors and the onset of anxiety disorders in children: links with parental psychopathology. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;27:221-31. Crossref

- Sicouri G, Sharpe L, Hudson JL, et al. Threat interpretation and parental influences for children with asthma and anxiety. Behav Res Ther 2017;89:14-23. Crossref

- Studnek JR, Bentley M, Crawford JM, Fernandez AR. An assessment of key health indicators among emergency medical services professionals. Prehosp Emerg Care 2010;14:14-20. Crossref

- Lack S, Schechter MS, Everhart RS, Thacker Ii LR, Swift-Scanlan T, Kinser PA. A mindful yoga intervention for children with severe asthma: a pilot study. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2020;40:101212. Crossref

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther 2011;42:676-88. Crossref

- Bonner MJ, Hardy KK, Willard VW, Hutchinson KC, Guill AB. Further validation of the parent experience of child illness scale. Child Health Care 2008;37:145-57. Crossref

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2005;44:227-39. Crossref

- Nauta MH, Scholing A, Rapee RM, Abbott M, Spence SH, Waters A. A parent-report measure of children’s anxiety: psychometric properties and comparison with child-report in a clinic and normal sample. Behav Res Ther 2004;42:813-39. Crossref

- Karkhanis VS, Joshi JM. Spirometry in chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD). J Assoc Physicians India 2012;60(Suppl):22-6.

- Kline RB. Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling. In: Handbook of Methodological Innovation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011:562-89. Crossref

- Yamamoto N, Nagano J. Parental stress and the onset and course of childhood asthma. Biopsychosoc Med 2015;9:7. Crossref

- Wood BL, Brown ES, Lehman HK, Khan DA, Lee MJ, Miller BD. The effects of caregiver depression on childhood asthma: pathways and mechanisms. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;121:421-7. Crossref

- Leiferman J. The effect of maternal depressive symptomatology on maternal behaviors associated with child health. Health Educ Behav 2002;29:596-607. Crossref

- Bartlett SJ, Krishnan JA, Riekert KA, Butz AM, Malveaux FJ, Rand CS. Maternal depressive symptoms and adherence to therapy in inner-city children with asthma. Pediatrics 2004;113:229-37. Crossref

- Pappalardo AA, Weinstein S. The anxiety-asthma relationship: risk or resilience? J Pediatr 2019;214:8-10. Crossref

- Sastre J, Crespo A, Fernandez-Sanchez A, Rial M, Plaza V; investigators of the CONCORD Study Group. Anxiety, depression, and asthma control: changes after standardized treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:1953-9. Crossref