East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2023;33:120-5 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2334

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Abstract

Objective: To identify factors associated with the use and duration of physical restraint (PR) in a psychiatric unit in Japan.

Methods: Medical records of 1308 patients admitted first time to the psychiatric emergency unit of Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2021 were retrospectively reviewed. Data collected included patient age, sex, outpatient treatment, living arrangements, disability pension status, diagnosis (based on ICD-10), and psychotropic medication use at admission (chlorpromazine equivalent dose, imipramine equivalent dose, diazepam equivalent dose, and number of mood stabilisers administered). Logistic regression analysis and multiple regression analysis were used to identify factors associated with the use and duration of PR, respectively.

Results: Of 1308 patients, 399 (30.5%) were subjected to PR and 909 (69.5%) were not. Among the 399 patients subjected to PR, 54 were excluded from the multiple regression analysis for duration of PR as they remained subject to PR on the day of discharge. The remaining 345 patients were subject to PR for a median of 10 days. PR utilisation was associated with male sex (odds ratio [OR] = 1.420), treatment at our hospital (OR = 0.260), treatment at other hospitals (OR = 0.645), F3 diagnosis (depression) [OR = 0.290], F4-9 diagnosis (OR = 0.309), and imipramine equivalent dose at admission (unit OR = 0.994). The log-transformed duration of PR was independently associated with the age group of 50 to 69 years (β = 0.248), the age group of ≥70 years (β = 0.274), receiving a disability pension (β = 0.153), an F1 diagnosis (β = -0.187), an F4-9 diagnosis (β = -0.182), chlorpromazine equivalent dose at admission (β = 0.0004), and number of mood stabilisers administered at admission (β = −0.270).

Conclusion: Identifying factors associated with the use and duration of PR may lead to reduction in the use and duration of PR.

Keita Kawai, Mental Care Center, Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan and Department of Psychiatry, Showa University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

Hiroki Yamada, Mental Care Center, Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan and Department of Psychiatry, Showa University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

Hiroi Tomioka, Mental Care Center, Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan and Department of Psychiatry, Showa University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

Akira Iwanami, Department of Psychiatry, Showa University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

Atsuko Inamoto, Mental Care Center, Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan and Department of Psychiatry, Showa University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

Address for correspondence: Dr Keita Kawai, Mental Care Center, Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital, 35-1 Chigasakichuo, Yokohama Tsuzuki Ward, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, 224-8503. Email: kawai.keita@med.showa-u.ac.jp

Submitted: 5 July 2023; Accepted: 18 October 2023

Introduction

Coercive measures such as physical restraint (PR) and seclusion are used in psychiatric practice worldwide. However, the negative ramifications of such measures have garnered increasing attention,1-6 and efforts to decrease their usage have been implemented, particularly in developed nations.7 Owing to the varying types of such measures and the legal and clinical requirements governing their use, consensus is difficult to achieve, and heterogeneity is substantial across studies.8-10 Such measures must be individualised, considering the circumstances of their usage, purpose, and effect.

PR carries severe risks such as physical injury, thrombosis, and aspiration pneumonia.3,4,6 Identifying the risks of PR and evaluating the use and duration of PR could help to develop comprehensive treatment plans and reduce the use of PR.8

Immigrants, individuals with mood disorders and/or schizophrenia, and patients in rural hospitals are at increased risk of PR,8 whereas male sex, young age, involuntary hospitalisation, and a diagnosis of schizophrenia are associated with increased risks of mechanical restraint.11

Duration of PR is associated with male sex, younger age, involuntary hospitalisation, concomitant pharmacological restraint, nationality, race, neurodevelopmental disorder, psychotic disorders, number of beds in a unit, a multidisciplinary working group, and the number of psychologists in a unit.12-15

In Japan, the use of PR is common and the duration is long.1,4,16-19 A multicentre study of 146 patients in Japan revealed that duration of PR was longer for men and for those with schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (F2 diagnoses) than for those with mental and behavioural disorders secondary to psychoactive substance use (F1 diagnoses).16 However, the study did not consider pharmacotherapy or differentiate depression from bipolar affective disorder. In a study of 241 restrained and 1093 unrestrained patients in Japan, the use of PR was associated with male sex, number of previous hospitalisations, organic (including symptomatic) mental disorders (F0 diagnoses), F1 and F2 diagnoses, lack of treatment history, transfer from other departments, admission after hours, involuntary admission, complications (such as neoplasms, diseases of the circulatory, respiratory, digestive or musculoskeletal systems, infectious diseases, and pregnancy), and history of suicide attempt, whereas the longer duration of PR was associated with complications.17 However, this study used univariate analysis only and did not control for confounders. In a multivariate analysis of 58 patients in Japan, prolonged seclusion and PR was associated with Alzheimer disease and major depressive disorder.18 However, the study did not differentiate seclusion from PR owing to the small sample size.

In Japan, only mental health professionals designated by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare can initiate PRs; other physicians can terminate their use. Therefore, initiation and termination of PRs are different clinical decisions. This study aimed to identify factors associated with PR utilisation and duration in a psychiatric unit in Japan.

Methods

Medical records of patients admitted to the psychiatric emergency unit (42 beds, 1 nurse per 10 patients) of Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2021 were retrospectively reviewed. Of 1699 admissions, 1308 were first-time admissions and were included in analysis.

PR was defined as a restriction of behaviour where the patient’s body is temporarily restrained using clothing or a cotton belt to restrain movement.20 In Japan, PRs are commonly lifted for a limited time during the day. Thus, even if PR was used for a short period in a single day, this was counted. When PR duration could not be measured in manner deemed suitable, these cases were excluded from the analyses. Data regarding PR duration were not normally distributed and therefore were log transformed in the multivariate analysis.

Age was categorised as ≤29 years, 30 to 49 years, 50 to 69 years, and ≥70 years because age may not have been linearly proportional to PR utilisation or duration. Living situation before admission was categorised as living alone and living with someone. Diagnoses were made in accordance with the ICD-10 as F0, F1, F2, F3 (bipolar affective disorder), F3 (depression), and F4-9. Usage of psychotropic drugs (chlorpromazine, imipramine, and diazepam) at admission was collected, as was the number of mood stabilisers administered at admission.

Logistic regression analysis was performed using the forced-entry method, with PR utilisation as the dependent variable, after adjustment for confounders. Dummy variables were created as covariates for categorical variables with ≥3 groups. The variance inflation factor was calculated, and multicollinearity was examined. Multiple regression analysis using the forced-entry method was performed for the PR group, with the log-transformed duration of PR as the dependent variable, after adjustment for confounders. All tests were two-tailed, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (Windows version 25.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], USA).

Results

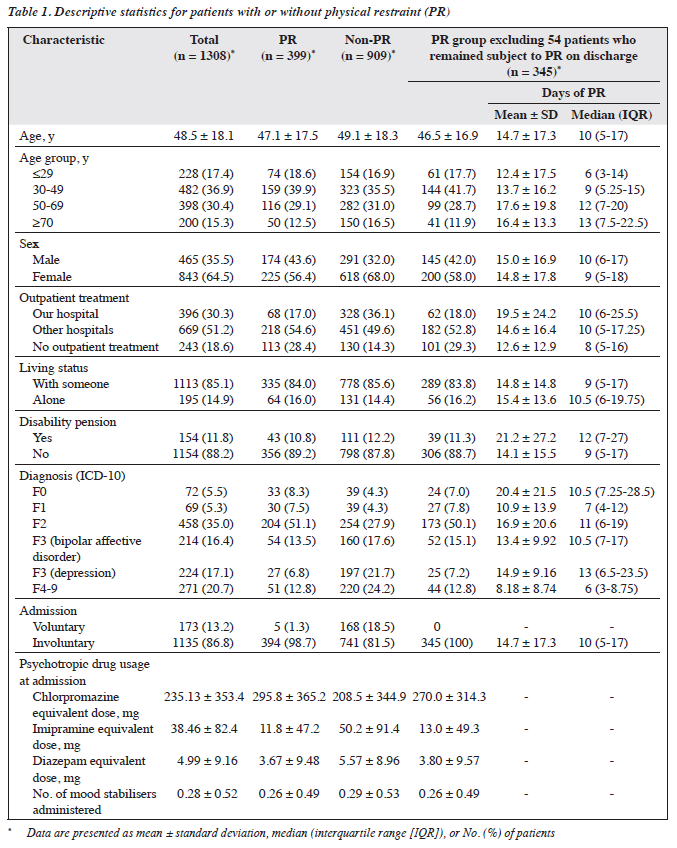

Of 1308 patients, 399 (30.5%) were subjected to PR and 909 (69.5%) were not (Table 1). Among the 399 patients subjected to PR, 54 were excluded from the multiple regression analysis for duration of PR as they remained subject to PR on the day of discharge. The remaining 345 patients were subject to PR for a mean ± standard deviation of 14.7 ± 17.3 days and a median (range) of 10 (5-17) days.

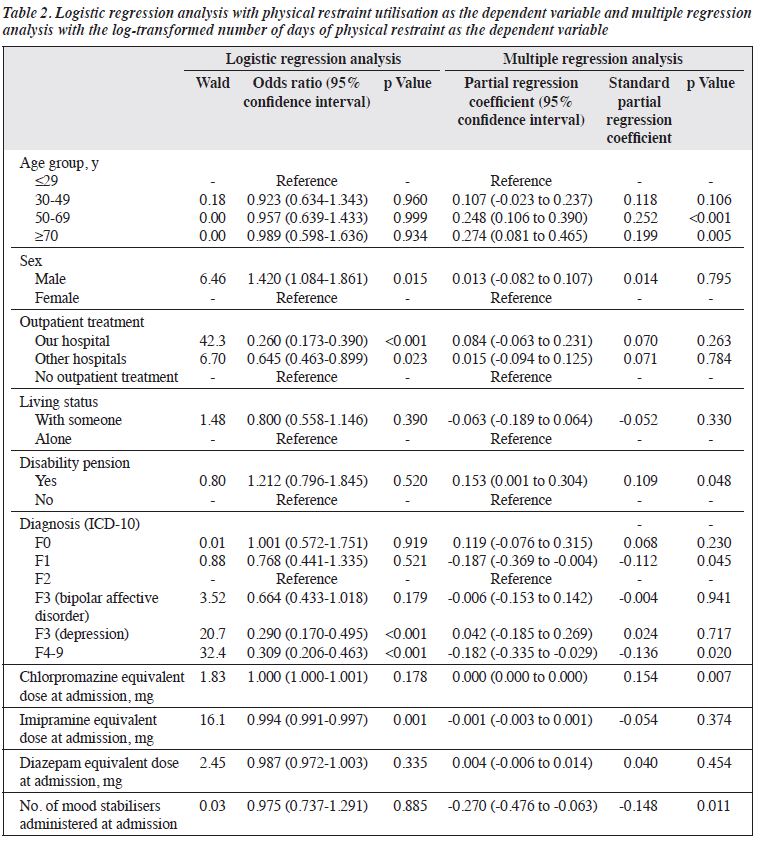

In a logistic regression analysis, PR utilisation was associated with male sex (odds ratio [OR] = 1.420, p = 0.02), treatment at our hospital (OR = 0.260, p < 0.001), treatment at other hospitals (OR = 0.645, p = 0.02), F3 diagnosis (depression) [OR = 0.290, p < 0.001], F4-9 diagnosis (OR = 0.309, p < 0.001), and imipramine equivalent dose at admission (unit OR = 0.994, p = 0.001) [Table 2]. The maximum variance inflation factor value was <2.2, which indicated that multicollinearity was not a concern.

In a multiple regression analysis of the 345 patients who were subject to PR (excluding those who remained subject to PR on discharge), the log-transformed duration of PR was independently associated with the age group of 50 to 69 years (β = 0.248, p < 0.001), the age group of ≥70 years (β = 0.274, p = 0.01), receiving a disability pension (β = 0.153, p = 0.048), an F1 diagnosis (β = -0.187, p = 0.045), an F4-9 diagnosis (β = -0.182, p = 0.02), chlorpromazine equivalent dose at admission (β = 0.0004, p = 0.007), and number of mood stabilisers administered at admission (β = -0.270, p = 0.01) [Table 2].

Discussion

PR utilisation and duration is high in Japan.1,4,16-19 In the present study, 30.5% of patients were subject to PR for a median 10 days, which was higher than the rates of 12.0% for a median of 82 hours16 and 18.1% for 4 to 7 days17 reported in other studies in Japan. The rate of PR use was also high in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan; it appears to be a common trend in East Asia.21-23 This might be due to a lower nurse-patient ratio.16

In the present study, the higher PR utilisation may be due to the high number of patients at imminent risk of suicide or violence, after-hour admissions, complications, involuntary admissions, and unit structure.11,12,17 In our unit, all 42 beds were in closed units and 86.8% of admissions were involuntary. However, in a similar study in Japan, 28 of 50 beds were in open units and 65.8% of admissions were involuntary.17 In addition, the longer PR duration in the present study may be due to the use of a whole-day increment, rather than the use of 4-, 12-, 20-, and 24-hour increments in a study in Japan.16 Standardising measurements across studies may help determine associations between hospital characteristics and PR utilisation.

In the present study, male sex was associated with PR utilisation but not duration. Results remain inconsistent owing to the limited research on PR duration.11-13,16-18,24-26 Although there were no sex disparities in observed violent conduct,27,28 the higher likelihood of PR use among male patients might be attributed to a perception among healthcare staff that male patients were more predisposed towards violence. Therefore, staff education may help to reduce PR use among male patients.

In the present study, older age groups were associated with PR duration but not utilisation, consistent with findings from a study in Japan.17 In contrast, studies in other countries reported that younger individuals were at a higher risk of PR11 and a longer duration of PR.12 Financial disincentives may have reduced PR utilisation among older people in acute general care wards in Japan.29 Similarly, PR duration may be shortened by optimisations in the healthcare system. The use of PR was lower if patients had received outpatient treatment before admission or had been treated in our hospital. However, this was not associated with duration of PR. This may be because our healthcare staff are familiar with the patients and have more clinical information about them. People are wary of strangers and thus ascribe a higher risk to them; this may lead to higher use of PR in patients from ethnic minority backgrounds.8,14 Furthermore, outpatient treatment was not associated with duration of PR. Vigilance is usually high during admission (because of limited patient information) but is relaxed after admission.

In the present study, disability pension status was associated with duration of PR but not utilisation of PR. In Japan, disability pensions are categorised based on the chronicity and severity of impairments in daily living and work-related capabilities, rather than the diagnosis or symptoms of the individuals. Diminution of these capabilities does not affect PR initiation but may prolong the duration of recovery in patients subject to PR.

In the present study, PR utilisation was lower in those with F3 (depression) and F4-9 diagnoses, compared with those with F2 diagnosis, whereas duration of PR was shorter in those with F1 and F4-9 diagnoses. PR was deemed not necessary in patients with an F3 (depression) diagnosis who have a likelihood of suicide attempts; seclusion is preferred. However, major depressive disorder is associated with prolonged duration of seclusion and PR.18 F4-9 diagnoses tend to be mild and thus PR utilisation is lower and PR duration is shorter.17 An F1 diagnosis was associated with a shorter PR duration but not PR utilisation. Substance abuse diagnoses can cause severe acute symptoms that require PR utilisation, but such patients recover sooner.16

In the present study, chlorpromazine equivalent dose was positively associated with PR duration. Patients who require higher doses of antipsychotics tend to have a longer recovery period. However, higher imipramine equivalent dose was associated with reduced PR utilisation, consistent with a study reporting association between antidepressant use and reduced PR utilisation.18 The number of mood stabilisers administered at admission was associated with PR duration but not utilisations, whereas medications at admission were associated with both PR utilisation and duration. In acute psychiatric settings, treatment is often initiated without a clear diagnosis. Medications at admission may be used to predict PR utilisation and duration regardless of the diagnosis.

Identifying factors associated with PR utilisation can help prevent incidents that may affect both patients and healthcare personnel, whereas identifying factors associated with duration of PR enables timely implementation of customised care.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a study of an emergency psychiatric unit in a general hospital, and thus the findings may not be generalisable to other settings. Multicentre studies are needed. Second, comorbidities were not included as variables in analysis. Third, the reasons for PR (such as violence, suicide, and treatment of physical illness) were not included in analysis. Inclusion of these variables may yield divergent results.

Conclusion

Identifying factors associated with the use and duration of PR may lead to reduction in the use and duration of PR.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by Showa University Research Ethics Review Board (reference: 2023-016-A). The patients were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eisuke Inoue for advice on statistical analysis.

References

- Hatta K, Shibata N, Ota T, et al. Association between physical restraint and drug-induced liver injury. Neuropsychobiology 2007;56:180-4. Crossref

- Rakhmatullina M, Taub A, Jacob T. Morbidity and mortality associated with the utilization of restraints: a review of literature. Psychiatr Q 2013;84:499-512. Crossref

- Poremski D, Loo E, Chan CYW, Li LD, Fung D. Reducing injury during restraint by crisis intervention in psychiatric wards in Singapore. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2019;29:129-35. Crossref

- Funayama M, Takata T. Psychiatric inpatients subjected to physical restraint have a higher risk of deep vein thrombosis and aspiration pneumonia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2020;62:1-5. Crossref

- Wu KK, Cheng JP, Leung J, Chow LP, Lee CC. Patients’ reports of traumatic experience and posttraumatic stress in psychiatric settings. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2020;30:3-11. Crossref

- Lee CC, Fung R, Pang SW, Lo TL. Pulmonary embolism as a cause of death in psychiatric inpatients: a case series. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2019;29:136-7. Crossref

- LeBel JL, Duxbury JA, Putkonen A, Sprague T, Rae C, Sharpe J. Multinational experiences in reducing and preventing the use of restraint and seclusion. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2014;52:22-9. Crossref

- Beames L, Onwumere J. Risk factors associated with use of coercive practices in adult mental health inpatients: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2022;29:220-39. Crossref

- Luciano M, Sampogna G, Del Vecchio V, et al. Use of coercive measures in mental health practice and its impact on outcome: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother 2014;14:131-41. Crossref

- Jacobsen TB. Involuntary treatment in Europe: different countries, different practices. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012;25:307-10. Crossref

- Beghi M, Peroni F, Gabola P, Rossetti A, Cornaggia CM. Prevalence and risk factors for the use of restraint in psychiatry: a systematic review. Riv Psichiatr 2013;48:10-22.

- Välimäki M, Lam YTJ, Hipp K, et al. Physical restraint events in psychiatric hospitals in Hong Kong: a cohort register study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:6032. Crossref

- Knutzen M, Bjørkly S, Eidhammer G, et al. Mechanical and pharmacological restraints in acute psychiatric wards--why and how are they used? Psychiatry Res 2013;209:91-7. Crossref

- Porat S, Bornstein J, Shemesh AA. The use of restraint on patients in Israeli psychiatric hospitals. Br J Nurs 1997;6:864-73. Crossref

- Sangiorgio P, Sarlatto C. Physical restraint in general hospital psychiatric units in the metropolitan area of Rome. Int J Ment Health 2008;37:3-16. Crossref

- Noda T, Sugiyama N, Sato M, et al. Influence of patient characteristics on duration of seclusion/restrain in acute psychiatric settings in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2013;67:405-11. Crossref

- Odawara T, Narita H, Yamada Y, Fujita J, Yamada T, Hirayasu Y. Use of restraint in a general hospital psychiatric unit in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005;59:605-9. Crossref

- Narita Z, Inagawa T, Yokoi Y, et al. Factors associated with the use and longer duration of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient settings: a retrospective chart review. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2019;23:231-5. Crossref

- Hübner-Liebermann B, Spiessl H, Iwai K, Cording C. Treatment of schizophrenia: implications derived from an intercultural hospital comparison between Germany and Japan. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2005;51:83-96. Crossref

- Bleijlevens MH, Wagner LM, Capezuti E, Hamers JP, International Physical Restraint Workgroup. Physical restraints: consensus of a research definition using a modified Delphi technique. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:2307-10. Crossref

- An FR, Sha S, Zhang QE, et al. Physical restraint for psychiatric patients and its associations with clinical characteristics and the national mental health law in China. Psychiatry Res 2016;241:154-8. Crossref

- Wu WW. Psychosocial correlates of patients being physically restrained within the first 7 days in an acute psychiatric admission ward: retrospective case record review. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:47-57.

- Chien CF, Huang LC, Chang YP, Lin CF, Hsu CC, Yang YH. What factors contribute to the need for physical restraint in institutionalized residents in Taiwan? PLoS One 2022;17:e0276058. Crossref

- Zhu XM, Xiang YT, Zhou JS, et al. Frequency of physical restraint and its associations with demographic and clinical characteristics in a Chinese psychiatric institution. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2014;50:251-6. Crossref

- Migon MN, Coutinho ES, Huf G, Adams CE, Cunha GM, Allen MH. Factors associated with the use of physical restraints for agitated patients in psychiatric emergency rooms. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008;30:263-8. Crossref

- Green-Hennessy S, Hennessy KD. Predictors of seclusion or restraint use within residential treatment centers for children and adolescents. Psychiatr Q 2015;86:545-54. Crossref

- Mellesdal L. Aggression on a psychiatric acute ward: a three-year prospective study. Psychol Rep 2003;92:1229-48. Crossref

- Barlow K, Grenyer B, Ilkiw-Lavalle O. Prevalence and precipitants of aggression in psychiatric inpatient units. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2000;34:967-74. Crossref

- Nakanishi M, Okumura Y, Ogawa A. Physical restraint to patients with dementia in acute physical care settings: effect of the financial incentive to acute care hospitals. Int Psychogeriatr 2018;30:991-1000. Crossref