East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2024;34:134-40 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2451

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Abstract

Background: The use of actors as standardised patient-instructors (SPI) in clinical interview training in the psychiatry module of the medical curriculum is welcomed by medical students. This study aims to examine the effectiveness of this training in enhancing medical students’ psychiatric interview skills.

Methods: This was a single-blind randomised controlled study with two arms. Between 17 July 2023 and 26 January 2024, year 5 medical students of The Chinese University of Hong Kong who were studying the psychiatry module and had completed the introductory lecture on clinical interview skills were invited to participate. Participants were asked to rate (1) the helpfulness and adequacy of the existing clinical interview training and (2) their confidence in implementing the clinical interview skills. Participants were then randomly assigned to the intervention group or the control group. Participants in the intervention group received a single clinical interview training workshop through a teleconference platform around mid-module, whereas participants in the control group received teaching as usual. Each workshop involved one trained SPI and two students and lasted for 2 hours. Students engaged in two psychiatric scenarios (post-traumatic stress disorder and delusional disorder). The actor interacted with the students and then provided feedback and guidance based on the four key learning points, namely respectful and sincere attitude, attunement, reflective listening, and empathetic understanding. While one student was practising with the actor, the other student observed and provided peer feedback. Outcome measures included the interview skill sub-score and total score of the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) at the end of the module, as well as perceptions of participants on the workshop.

Results: Of 279 eligible students, 112 were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=58, 52% female) or the control group (n=54, 52% female). The intervention and control groups were comparable in terms of module-end written examination score, interview skill sub-score of OSCE, and total score of OSCE. Despite this, participants provided highly positive feedback for the clinical interview training using the SPI approach, and 98.3% considered that the session had a positive effect on clinical communication skills. Nonetheless, the post-workshop confidence levels of participants were not correlated with the interview skill sub-score or the total score of OSCE. Similarly, participants’ perceived positive feedback of the workshop was not correlated with the Interview skill sub-score or the total score of OSCE.

Conclusion: Small-group online clinical interview training using the SPI approach is welcomed by students. Positive subjective outcomes may not match with objective outcomes. Further studies are needed to establish the benefit of the SPI approach.

Alice Ling Tsui, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Steven Wai Ho Chau, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Address for correspondence: Dr Steven Wai Ho Chau, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: stevenwhchau@gmail.com

Submitted: 24 September 2024; Accepted: 8 November 2011

Clinical interview enables physicians to obtain detailed and accurate medical histories from patients. Clinical interview skills are particularly important for psychiatrists, because success in diagnosing and treating patients relies heavily on clinical interviews and trustful doctor-patient rapport. In medical education curricula, standardised patients (SP) trained to portray specific medical scenarios are often involved in clinical training and examination, interacting with students and training their history-taking and counselling skills.1-4 SP provide a controlled environment for healthcare professionals to practise and refine their communication skills and diagnostic reasoning during clinical interviews.5 The use of SP is effective in enhancing the clinical interview skills of trainees and their confidence in conducting such interviews.3,6-11 In a review comparing the SP approach with other approaches (including role-play, mannequin, and visual SP), subjective outcomes in terms of skills improvement and attitude adjustment are usually positive, but improvement in objective outcomes is seldom found.12 Using professional actors as SP in clinical interview training has prompted positive participant feedback.13

In the standardised patient-as-instructor (SPI) approach, SP can become instructors and provide feedback as patients as well as guidance for improvement during clinical interview and communication training.14-23 Nonetheless, randomised controlled studies of the SPI approach with objective outcome measures using validated instruments are limited.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, clinical attachments were disrupted. We explored innovative teaching approaches using trained professional actors as SPIs to provide students with direct observation and guidance via teleconference platforms. In our pilot study, a small-group online clinical interview training using the SPI approach was rated favourably by students across subjective measures.24 The present study aims to examine the effectiveness of this training in enhancing medical students’ psychiatric interview skills. Our findings may provide evidence supporting the use of such training in the standard medical curriculum.

Methods

This was a single-blind randomised controlled study with two arms. Between 17 July 2023 and 26 January 2024, year 5 medical students of The Chinese University of Hong Kong who were studying the psychiatry module and had completed the introductory lecture on clinical interview skills were invited to participate via emails, which directed them to an online survey platform.

Participants were asked to rate on a five-point Likert scale regarding (1) the helpfulness and adequacy of the existing clinical interview training and (2) their confidence in implementing the clinical interview skills. Participants were then randomly assigned to the intervention group or the control group using a computer-generated blocks-of-four sequence. Participants in the intervention group received a single clinical interview training workshop through a teleconference platform around mid-module, whereas participants in the control group received teaching as usual. Each workshop involved one trained SPI and two students and lasted for 2 hours. Two actors delivered all workshops; both had participated in the pilot study. Students engaged in two psychiatric scenarios (post-traumatic stress disorder and delusional disorder). The actor interacted with the students and then provided feedback and guidance based on the four key learning points, namely respectful and sincere attitude, attunement, reflective listening, and empathetic understanding. While one student was practising with the actor, the other student observed and provided peer feedback.

The primary outcome measure was the interview skill sub-score of the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) at the end of the module. Students were required to take a focused history and perform a mental state examination for a SP, each within 8 minutes. Total interview skill sub-scores range from 0 to 20 and account for 20% of the total OSCE scores (the other two subscores are ‘content and approach’ and ‘presentation and viva’). Secondary outcome measures were immediate post-workshop perceptions of participants measured on a five-point Likert scale in terms of (1) realism and relevancy of the given clinical scenarios, (2) realism and helpfulness of the actor’s performance, (3) delivery of the four key learning points, (4) positive impact and expectation fulfilment, and (5) confidence to implement clinical interviews. The two groups were compared using the independent t-test.

Results

Of 279 eligible students, 112 were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=58, 52% female) or the control group (n=54, 52% female). One participant in the intervention group did not attend the workshop without any reason.

The intervention and control groups were comparable in terms of module-end written examination score (22.4±1.7 vs 22.4±1.8, t(110)= –0.055, p=0.956, d= –0.010), interview skill sub-score of OSCE (14.0±1.3 vs 13.8±1.3, t(110)= –0.546, p=0.586, d= –0.103), and total score of OSCE (41.3±3.8 vs 41.2±3.7, t(110)= –0.123, p=0.903, d= –0.023).

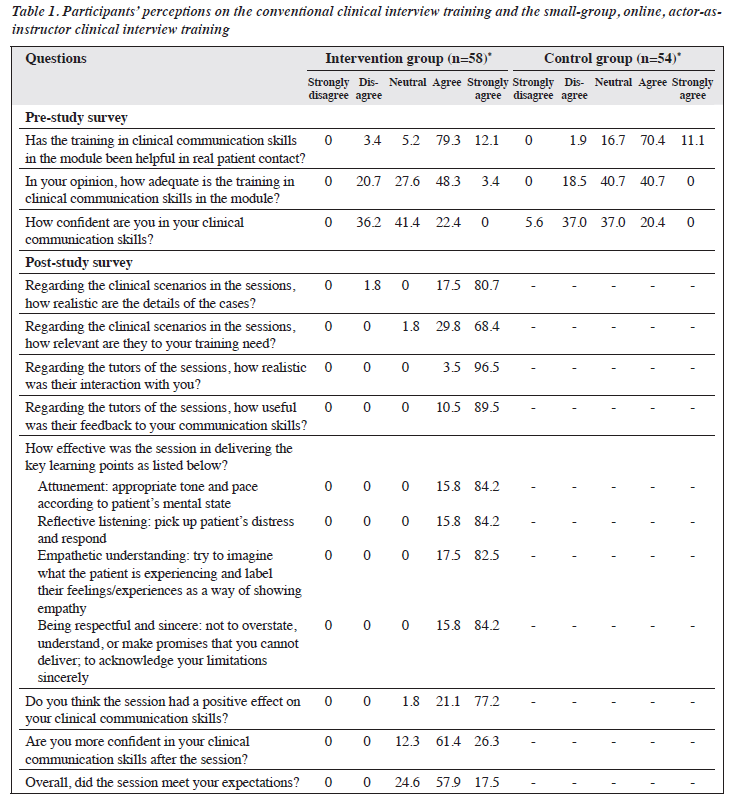

In the pre-study survey, respectively in the intervention and control groups, 91.4% and 81.5% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the conventional clinical interview training was helpful in real-life patient encounters, whereas 51.7% and 40.7% agreed or strongly agreed that the training to be inadequate, and 22.4% and 20.4% agreed or strongly agreed that they lacked confidence in conducting clinical interviews (Table 1).

In the post-study survey, participants in the intervention group expressed highly positive feedback regarding the training workshop conducted by the SPIs: 98.2% agreed or strongly agreed that the details were realistic and the training relevant; all participants agreed or strongly agreed that the interactions with the SPI were realistic and that the feedback from the SPIs on communication skills was useful; 98.3% considered that the session had a positive effect on clinical communication skills; 87.7% believed that they were more confident in conducting clinical interviews; and all considered that the workshop met their expectations (Table 1).

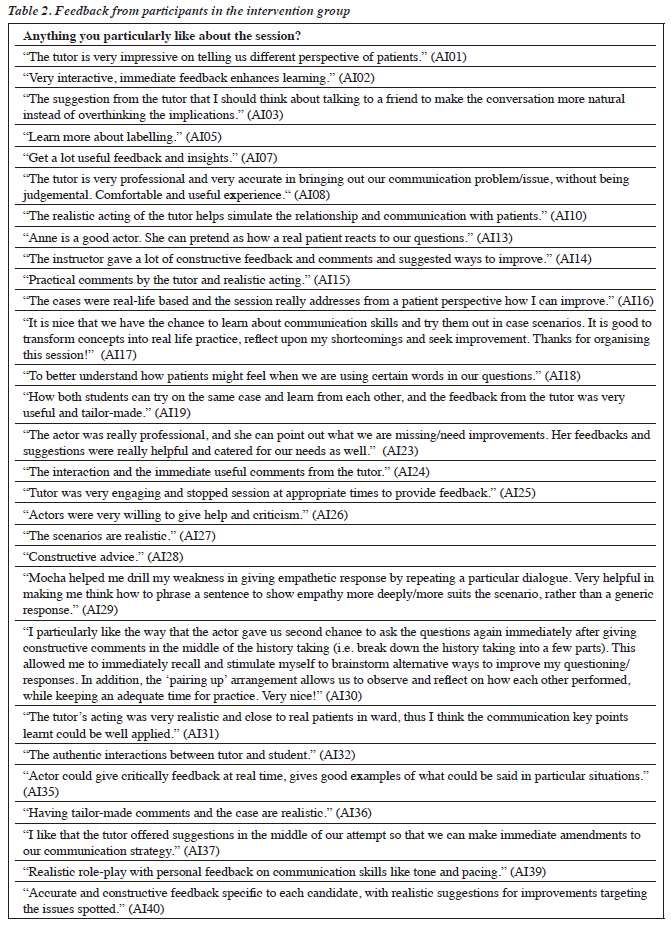

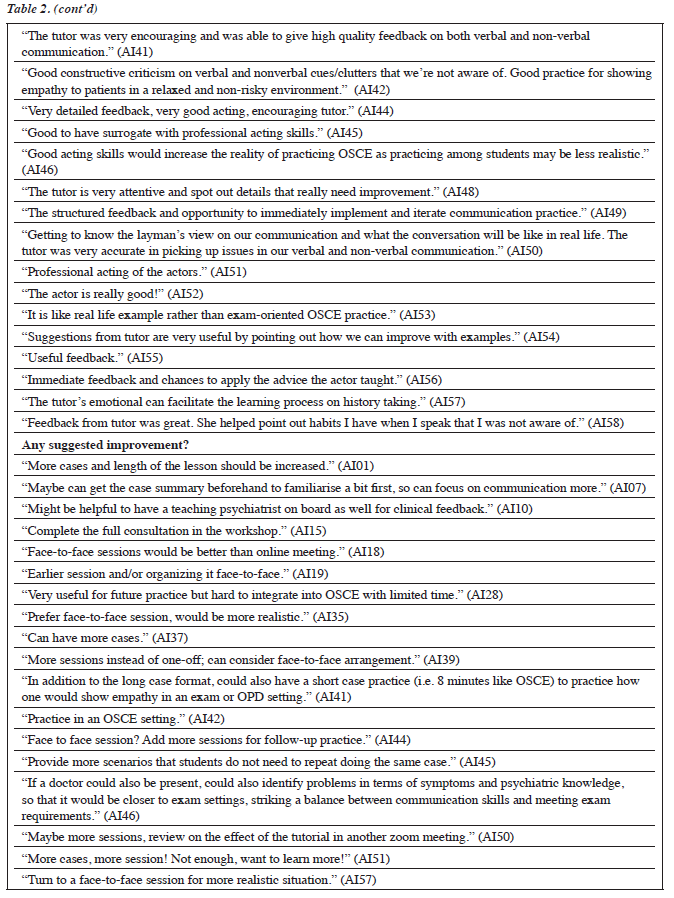

Participants provided positive feedback for the workshop (Table 2). They appreciated that the scenarios were realistic and that the feedback from the SPIs was useful and constructive. The realistic acting and feedback effectively guided participants to “transform concepts into real-life practice”, and “understand how patients might feel”. They were allowed to “drill the weakness in giving empathetic responses by repeating a particular dialogue” during the workshop. Additionally, participants provided suggestions for improvements such as “including more cases”, “having a teaching psychiatrist on board”, “adding more sessions”, and “practising in OSCE settings”. Some pointed out that the intervention was “very useful for future practice but hard to integrate into OSCE with limited time”.

The post-workshop confidence levels of participants were not correlated with the interview skill sub-score of OSCE (r= –0.092, p=0.495) or the total score of OSCE (r=0.011, p=0.934). Similarly, participants’ perceived positive feedback of the workshop was not correlated with the Interview skill sub-score of OSCE (r= –0.123, p=0.36) or the total score of OSCE (r= –0.091, p=0.503).

Discussion

Our medical students perceived that the conventional clinical interview training was inadequate and that they lacked confidence in conducting clinical interview. The ever-increasing content that needs to be taught in the medical curriculum may explain the lower priority assigned to clinical interview skills. Yet, in the field of psychiatry, communication skills affect clinical outcomes. The SPI approach, combined with teleconference technology, enhanced the conventional curriculum without adding a significant teaching burden, allowing for more flexible scheduling to prevent clashes in teaching timetables.

Participants enthusiastically embraced the small- group clinical interview training using the SPI approach delivered via a teleconference platform. They expressed satisfaction with the clinical scenario design. They appreciated the SPI approach for the acting, guidance, and feedback, acknowledging a positive effect on clinical interview skills. Most participants reported increased confidence in clinical interview skills. According to the feedback, the SPI approach in a small-group setting allowed students to practise and adjust their clinical interview style in a less stressful manner. The SPIs could provide immediate feedback on verbal and non-verbal expressions and facilitate empathetic understanding of the psyche of patients. The SPI approach also enabled greater flexibility in the pace of the practice, allowing students to stop and start at any point and repeat and try different approaches.

The use of professional actors was the key to success. Theatre training had equipped the actors to simulate the characters in given circumstances. This is particularly valuable, as it is difficult to portray a naturalistic clinical interview using prescribed scripts only, and improvisation is necessary. Participants commented that the actors could interact as patients with realistic acting, pinpoint communication problems during interactions, and provide constructive feedback.

Despite the positive subjective outcomes, the intervention and the control groups did not differ significantly in terms of the interview skill sub-score and total score of the OSCE. This may be due to the intervention design and the choice of objective outcome measures. The single workshop might not be enough to consolidate the skills learned; we also did not keep track of the post- workshop progress of participants. The workshops covered two scenarios only, rather than all scenarios in the syllabus and the OSCE. Similar interventions from other studies are generally more intensive and comprehensive.15,16 The workshop was a supplementary session to the curriculum, as a multiple-session programme could clash with the tight teaching schedule. Additionally, students are under great time pressure during the OSCE and therefore often prioritise information gathering over the more time-consuming clinical interview that addresses patients’ feelings and concerns to make a diagnosis. It is difficult to know whether the OSCE examiners, who are clinicians, evaluated students’ performance based solely on the interview skills. Supplementation with the patient’s opinion, for example, how comfortable they felt when talking to the students would provide an alternative perspective that is less influenced by the level of medical knowledge of the student. The use of tools that rate communication skills such as the Calgary Cambridge Checklist is suggested.7,15

The present study has several limitations. The small sample size may have resulted in inadequate statistical power. The sample may also be biased, as only about 40% of the eligible students signed up for the study. However, the randomised controlled design may have minimised selection, allocation, experimenter, and subject biases.

Conclusion

Small-group online clinical interview training using the SPI approach is welcomed by students. Positive subjective outcomes may not match with objective outcomes. Further studies are needed to establish the benefit of the SPI approach.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / support

This study was funded by the Course Development Grant Scheme (2022-25) by The Chinese University of Hong Kong (reference: 168-CDG-S3). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Faculty Sub-committee, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (SBRE- 22-0693A), and the study protocol was registered in the OSF Registries (DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/JT68N). The participants provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

References

- May W, Park JH, Lee JP. A ten-year review of the literature on the use of standardized patients in teaching and learning: 1996-2005. Med Teacher 2009;31:487-92.

- Adamo G. Simulated and standardized patients in OSCEs: achievements and challenges 1992-2003. Med Teacher 2003;25:262- 70.

- Flanagan OL, Cummings KM. Standardized patients in medical education: a review of the literature. Cureus 2023. Accessed 13 May 2024. Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/167496-standardized-patients-in-medical-education-a-review-of-the-literature

- Carroll JG, Monroe J. Teaching clinical interviewing in the health professions: a review of empirical research. Eval Health Prof 1980;3:21-45.

- Howley LD. Standardized patients. In: The Comprehensive Textbook of Healthcare Simulation. 2013: 173-90.

- Birndorf CA. Teaching the mental status examination to medical students by using a standardized patient in a large group setting. Acad Psychiatry 2002;26:180-3.

- Geoffroy PA, Delyon J, Strullu M, et al. Standardized patients or conventional lecture for teaching communication skills to undergraduate medical students: a randomized controlled study. Psychiatry Investig 2020;17:299-305.

- Piette A, Muchirahondo F, Mangezi W, et al. Simulation-based learning in psychiatry for undergraduates at the University of Zimbabwe medical school. BMC Med Educ 2015;15:23.

- Doyle Howley L, Martindale J. The efficacy of standardized patient feedback in clinical teaching: a mixed methods analysis. Med Educ Online 2004;9:4356.

- Robins LS, Alexander GL, Dicken LL, Belville WD, Zweifler AJ. The effect of a standardized patient instructor experience on students’ anxiety and confidence levels performing the male genitorectal examination. Teaching Learning Med 1997;9:264-9.

- Himmelbauer M, Seitz T, Seidman C, Löffler-Stastka H. Standardized patients in psychiatry: the best way to learn clinical skills? BMC Med Educ 2018;18:72.

- Rutherford-Hemming T, Herrington A, Ngo TP. The use of standardized patients to teach communication skills—a systematic review. Sim

Healthcare 2024;19(1S):S122-8.

- Siemerkus J, Petrescu AS, Köchli L, Stephan KE, Schmidt H. Using standardized patients for undergraduate clinical skills training in an introductory course to psychiatry. BMC Med Educ 2023;23:159.

- Sharp PC, Pearce KA, Konen JC, Knudson MP. Using standardized patient instructors to teach health promotion interviewing skills. PubMed 1996;28:103-6.

- Shirazi M, Sadeghi M, Emami A, et al. Training and validation of standardized patients for unannounced assessment of physicians’ management of depression. Acad Psychiatry 2011;35:382-7.

- Levenkron JC, Greenland P, Bowley N. Using patient instructors to teach behavioral counseling skills. Acad Med 1987;62:665-72.

- Wagenschutz H, Ross P, Purkiss J, Yang J, Middlemas S, Lypson M. Standardized patient instructor (SPI) interactions are a viable way to teach medical students about health behavior counseling. Patient Educ Counseling 2011;84:271-4.

- Hardee JT. From standardized patient to care actor: evolution of a teaching methodology. Perm J 2005;9:79-82.

- Mavis B, Turner J, Lovell K, Wagner D. Developments: faculty, students, and actors as standardized patients: expanding opportunities for performance assessment. Teaching Learning Med 2006;18:130-6.

- Williams BC, Hall KE, Supiano MA, Fitzgerald JT, Halter JB. Development of a standardized patient instructor to teach functional assessment and communication skills to medical students and house officers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1447-52.

- Henry SG, Fenton JJ, Campbell CI, et al. Development and testing of a communication intervention to improve chronic pain management in primary care. Clin J Pain 2022;38:620-31.

- Bagacean C, Cousin I, Ubertini AH, et al. Simulated patient and role play methodologies for communication skills and empathy training of undergraduate medical students. BMC Med Educ 2020;20:491.

- Mert Karadas M, Terzioglu F. The impact of the using high-fidelity simulation and standardized patients to management of postpartum hemorrhage in undergraduate nursing students: a randomized controlled study in Turkey. Health Care Women Int 2019;40:597-612.

- Chau SWH. Can actors act as tutors for psychiatric clinical skills? Med Educ 2023;57:476-7.