East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2025;35:37-49 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2449

REVIEW ARTICLE

Suciwati Santoso, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia

Kenneth Tan, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia

Steffanie Irena Sidharta, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia

Naufal Rafif, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia

Tyasno Koeshermanto, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia

Theda Renanita, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia

Benedictus, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia

Muhana Fawwazy Ilyas, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia

Address for correspondence: Ms Suciwati Santoso, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia. Email: suci.r3dk@student.uns.ac.id

Submitted: 9 September 2024; Accepted: 19 February 2025

Abstract

Objectives: To review the literature regarding psychotherapeutic modalities for phantom limb pain (PLP).

Methods: The PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Scopus databases were searched to identify English- language studies, including review articles, related to psychotherapeutic modalities for PLP published before December 2024. Non-English-language studies, books, book chapters, or unpublished literature were excluded.

Results: In total, 55 studies were included in the analysis. There were 28 original studies (such as randomised controlled trials, clinical trials, observational studies, experimental studies, pilot studies, cohort studies, etc), 16 case reports or case series, nine systematic or narrative reviews, one case report with review, and one Delphi study. The most commonly used modality for PLP was mirror therapy, followed by virtual reality or augmented reality therapy, motor imagery, hypnotherapy, eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, graded motor imagery, virtual feedback, biofeedback, imaginative resonance training, cognitive behavioural therapy, auditory feedback, neurofeedback, thermal biofeedback, illusory touch, mental imagery, group therapy, and phantom exercises.

Conclusion: PLP is a complex condition encompassing physiological, psychological, and social factors. Due to its biopsychosocial nature, pharmacological treatments alone provide limited relief. Psychotherapeutic modalities have demonstrated effectiveness in treating PLP. Mirror therapy and virtual/augmented reality therapy are among the most commonly used modalities. The combined use of multiple psychotherapeutic modalities is more beneficial than standalone approaches.

Introduction

The phenomenon of phantom limb pain (PLP) is characterised by a painful sensation in an amputated limb, through which muscle motion is governed by a perception of that motion. Amputees continue to perceive pain and a sense of the amputated limb’s position.1 Other terms for this phenomenon include phantom sensation, phantom pain, and stump pain. Phantom sensation refers to any non-painful sensation occurring in the missing limb or organ, whereas phantom pain refers to painful sensations, and stump pain refers to pain at the site of amputation. Phantom limb sensation is most pronounced in individuals with above- the-elbow amputations and least pronounced in those with below-the-knee amputations. It occurs in 85% to 95% of amputees within the first 3 weeks after amputation; in some cases, it occurs between 1 and 12 months post-amputation, with a large percentage of cases progressing to PLP.2 Other pain conditions associated with PLP include headache or joint pain (35%), sore throat (28%), abdominal pain (18%), and back pain (13%).3

A meta-analysis estimated that the prevalence of PLP in amputees was 64%, with significantly lower prevalence in developing countries, possibly owing to under-reporting.4 Persistent PLP is associated with reduced quality of life and mental well-being.

Treatment modalities for PLP focus on symptomatic management; they include pharmacological interventions, non-invasive procedures, and psychological therapies. The most commonly used pharmacological intervention involves non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.5 Opioids such as tapentadol may be combined with neural-modulating agents.6,7 Antidepressants, particularly amitriptyline, have shown mixed results.8 Anticonvulsants,9,10 N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists such as ketamine,11 and topical analgesics12,13 have also shown mixed results.

Psychotherapeutic modalities address behavioural, cognitive, emotional, and social factors closely linked to pain perception; therefore, they are both effective and cost-effective.14-16 Such modalities include mirror therapy17 and virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR).18,19 This study aimed to review the literature regarding psychotherapeutic modalities for PLP.

Methods

This scoping review followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews.20 The PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Scopus databases were searched using the following keywords: ‘Phantom limb pain’ AND ‘Psychotherapy’ OR ‘Psychotherapy, psychodynamic’ OR

‘Imagery, psychotherapy’ OR ‘Psychotherapy, rational- emotive’ OR ‘Psychotherapy, multiple’ OR ‘Psychotherapy, brief’ OR ‘Psychotherapy, group’ OR ‘Person-centered psychotherapy’ OR ‘Interpersonal psychotherapy’ OR ‘Equine-assisted therapy’ OR ‘Cognitive behavioral therapy’ OR ‘Dignity therapy’.

English-language studies, including review articles, published before December 2024 were included. Non- English-language studies, books, book chapters, or unpublished literature were excluded. Studies were screened for duplicates; abstracts were screened by two groups of two reviewers to determine inclusion status. Differing opinions were discussed; in the event of a stalemate, a fifth reviewer determined study inclusion. For review articles, quality, risk of bias, and clarity were independently assessed by each reviewer using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist.21-25

Results

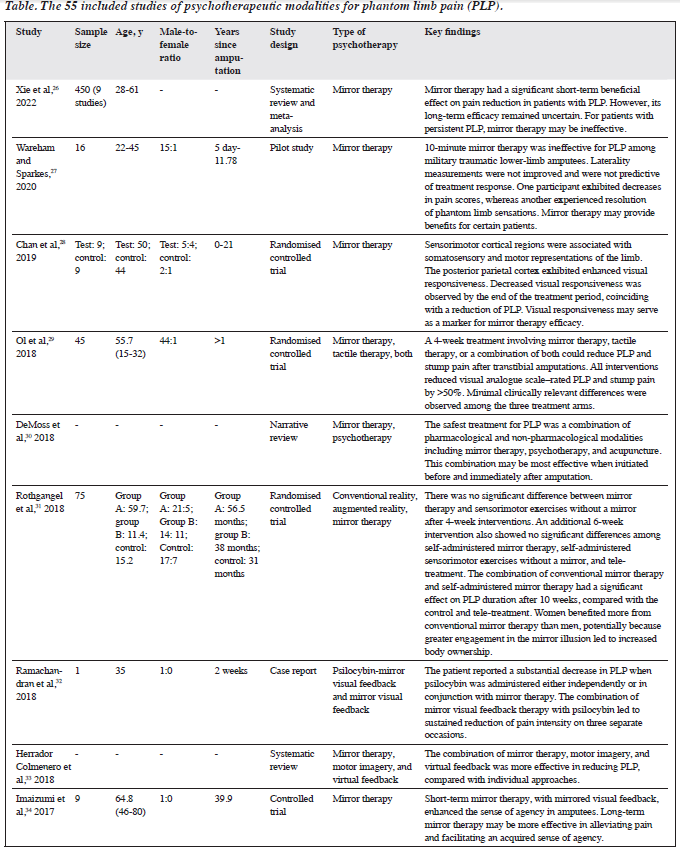

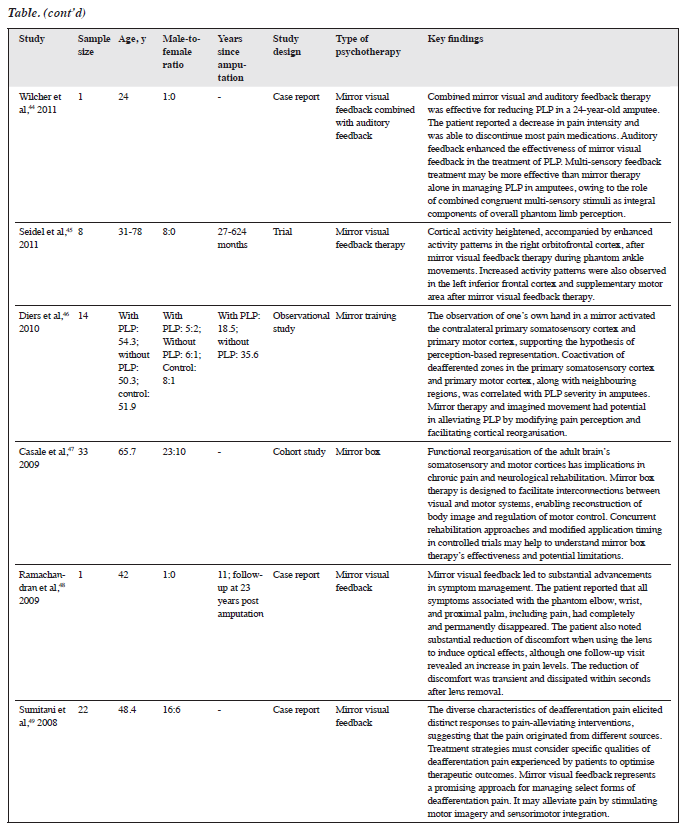

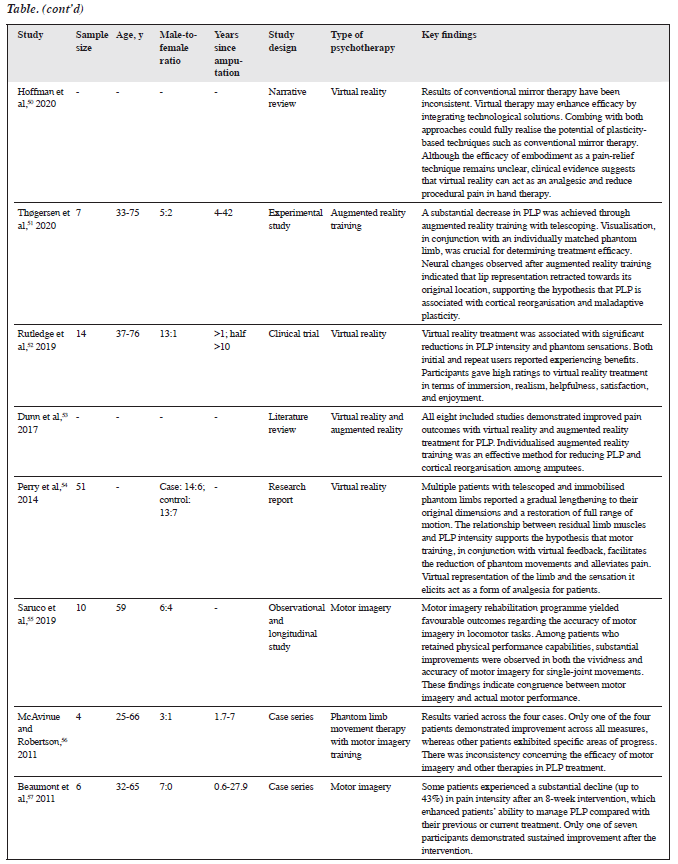

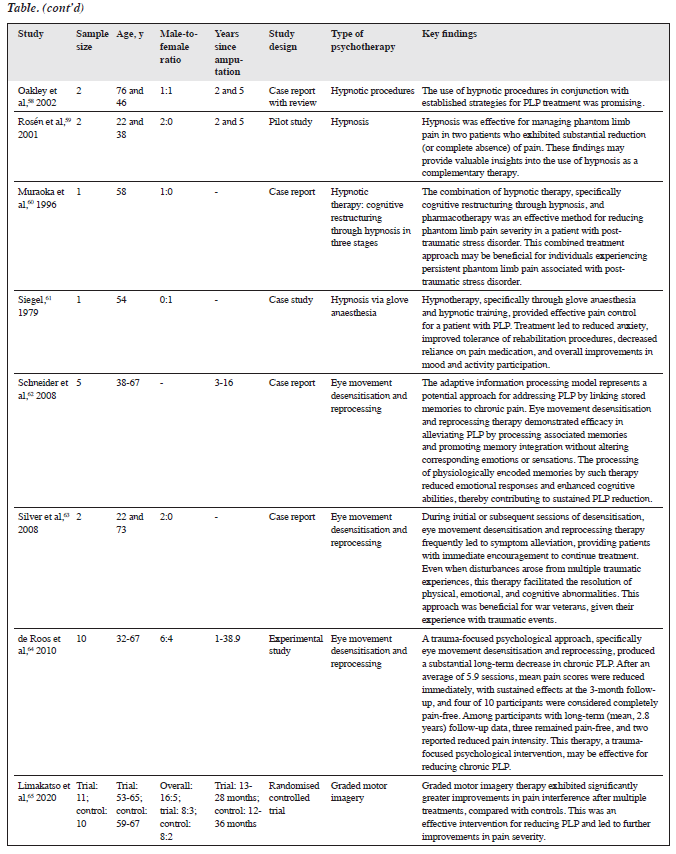

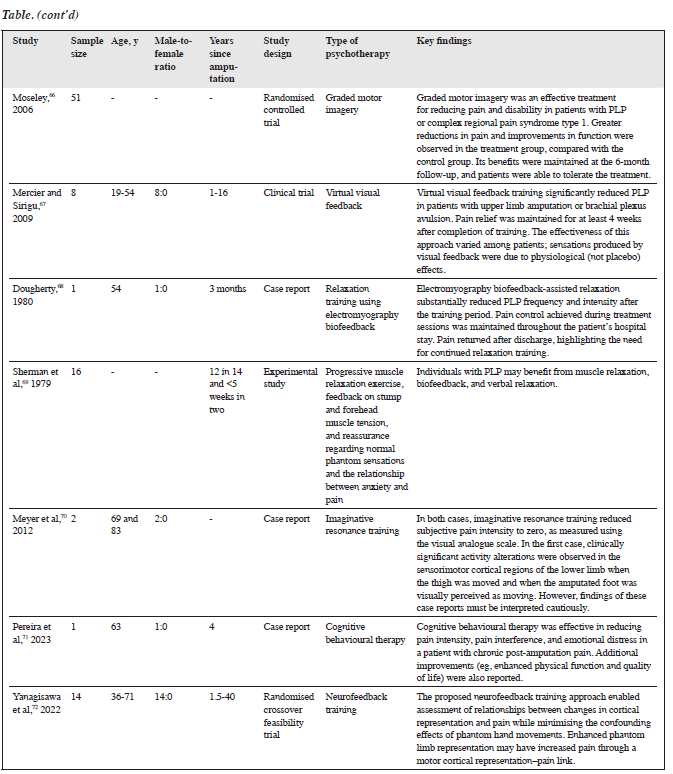

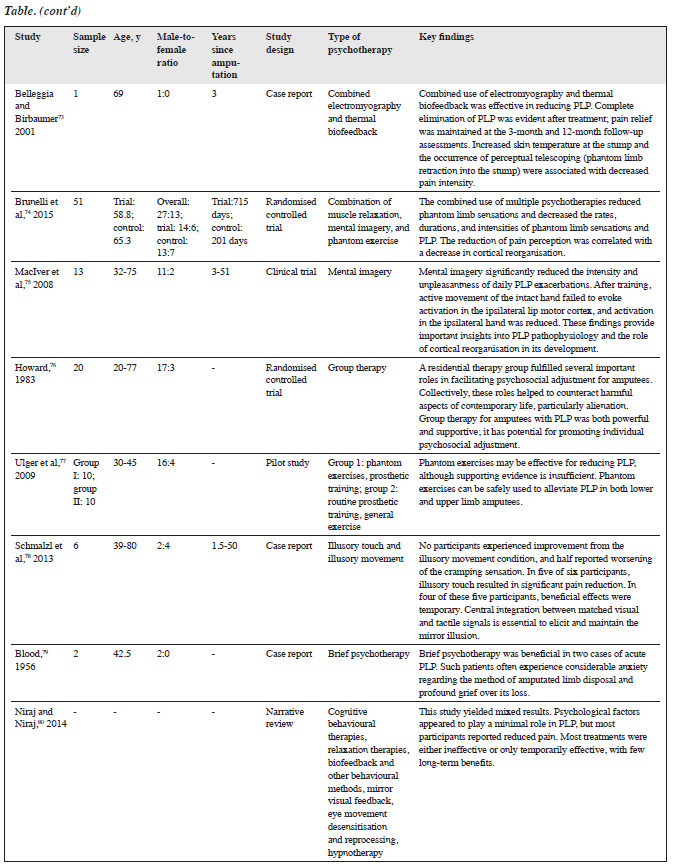

Of 994 studies identified (23 from PubMed PMC, 170 from PubMed, 680 from ScienceDirect, and 121 from Scopus), 169 were duplicates and therefore removed. The remaining 825 studies were screened. Of these, 332 did not target patients with PLP, 125 did not investigate psychotherapy, 157 were of inappropriate publication types, 20 were not written in English, and 136 investigated multiple modalities separately without comparisons (individual analyses of each modality were repetitive of other studies). The remaining 55 studies were included in the analysis (Table).26-80

There were 28 original studies (such as randomised controlled trials, clinical trials, observational studies, experimental studies, pilot studies, cohort studies, etc),27-29,31,34,36,39,40,42,43,45-47,51,52,54,55,59,64-67,69,72,74-77 16 case reports or case series,32,44,48,49,56,57,60-63,68,70,71,73,78,79 nine systematic or narrative reviews,26,30,33,35,37,38,50,53,80 one case report with review,58 and one Delphi study.41

The most commonly used modality for PLP was mirror therapy, also known as mirror visual feedback,26-49 followed by VR or AR therapy,31,40,42,50-54 motor imagery,33,55-57 hypnotherapy,58-61 eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR),62-64 graded motor imagery,65,66 virtual feedback,33,67 biofeedback,68,69 imaginative resonance training,70 cognitive behavioural therapy,71 auditory feedback,44 neurofeedback,72 thermal biofeedback,73 illusory touch,78 mental imagery,74,75 group therapy,76 and phantom exercises.77

Discussion

Most studies revealed positive effects of psychotherapy modalities on reducing PLP; however, some studies found no significant effect on pain alleviation,27,56,72,78 transient effects,57,78,80 or mixed results.80

From the 1950s to the 2000s, individual modalities such as hypnotherapy and group therapy were commonly used. Since 2010, a combination of multiple modalities has been used to improve efficacy. A 1956 study showed that patients experienced anxiety regarding disposal of the amputated limb and grief over its loss.79 Psychotherapies appear to be a means of reducing anxiety and grief. From the 1980s to the 2000s, biofeedback in conjunction with hypnotherapy and group therapy became more prevalent. Biofeedback can be combined with muscle relaxation and verbal relaxation, if necessary, for synergistic benefits.69 It appears to reduce the frequency and intensity of PLP after treatment; however, pain may recur, indicating the need for continued relaxation practice to maintain results.68 Group therapy has been shown to facilitate psychosocial adjustment and reduce anxiety.76 Hypnotherapy may decrease anxiety and improve mood, reduce PLP severity in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder, and be effectively combined with other treatments.60,61

From 2000 to 2010, mirror therapy, EMDR, graded motor imagery, phantom exercises, mental imagery, thermal biofeedback, and virtual feedback became more widely used. Mirror therapy has been the most utilised modality. EMDR has been shown to alleviate pain and is suitable for trauma-focused psychological interventions.62-64 Phantom exercises may reduce PLP, although the level of evidence is low. Thermal biofeedback operates by increasing skin temperature at the stump and inducing perceptual telescoping; temperature may play a role in pain intensity.73 Mental imagery operates by avoiding activation of the ipsilateral lip motor cortex and reducing activity in the ipsilateral hand.75 Cortical reorganisation may play an important role in these processes. Graded motor imagery, a combination of mirror therapy and motor imagery, is effective in alleviating pain and disability among patients with complex regional pain syndrome type 1 and those with PLP.66 Virtual feedback has demonstrated variable efficacy.67

2.png)

From 2010 to 2020, VR or AR was increasingly incorporated into other modalities such as motor training with virtual feedback51 and virtual advanced mirror therapy.28,37,39 All these modalities have shown positive effects, except for one that showed no significant effect relative to a mirror therapy-based approach lacking a mirror.31 VR has been shown to increase patient satisfaction by enhancing interactions between therapist and patient. Virtual feedback is complementary to other modalities; it reduces PLP when combined with mirror therapy and motor imagery.30 Motor imagery and graded motor imagery continue to be used in combination with other modalities.30 Effects on movement such as single-joint movements have been investigated.52 Graded motor imagery has demonstrated efficacy in alleviating pain and improving pain severity scores.

New modalities include auditory feedback, illusory touch, imaginative resonance training, neurofeedback, and cognitive behavioural therapy. Auditory feedback is effective when combined with mirror visual feedback. Combined congruent multisensory stimuli are more effective than mirror therapy without auditory feedback. Illusory touch is a potentially effective approach for PLP. Central integration between matched visual and tactile signals is crucial for eliciting the mirror illusion.78 Imaginative resonance training has been shown to reduce subjective pain intensity to zero, and changes in sensorimotor cortical activity are observed as the visual image of the amputated foot moves.70 Neurofeedback is associated with altered cortical representation in pain management and may minimise the effects of phantom movements.69 Cognitive behavioural therapy—as a standalone or combined modality—has demonstrated efficacy in reducing pain intensity, pain interference, and emotional distress, which may contribute to PLP.68,77,79

Mirror therapy

Mirror therapy is an inexpensive and simple technique for alleviating PLP symptoms81,82 and may be combined with other modalities.29,30,33,40,44 Also known as mirror visual feedback, it represents the third step of graded motor imagery after laterality training and imagined hand movements.83 In this approach, a mirror is positioned between the arms or legs to create the illusion of normal movement in the affected limb by reflecting the non-affected limb.84

Mirror therapy has been effective in managing complex regional pain syndrome type 1,82 as well as certain types of deafferentation pain, by stimulating motor imagery and sensorimotor integration in PLP;49 however, its effectiveness has been inconsistent.48 In some cases, mirror therapy permanently eliminates pain and associated PLP, whereas in others, the effects are transient. When a lens is used to trigger optical effects, the positive effects are often brief. Although pain reduction is clinically significant while the lens is in place, the effects do not persist after its removal. Mirror box therapy had limitations in its early development due to the lack of clinical results, undefined adverse effects, urgency of concurrent rehabilitation, and timing of application.47 From 2010 onwards, studies of mirror therapy for adjusting the brain’s perception of pain have shown that it can alter pain perception and facilitate cortical reorganisation.46 Activation of the contralateral primary somatosensory cortex and primary motor cortex suggests a perception-based representation associated with PLP severity in amputees,46 which is supported by findings of increased cortical activity in the right orbitofrontal cortex, left inferior frontal cortex, and supplementary motor area.45 Cortical reorganisation appears to restore the somatosensory cortices of both hemispheres to their presumed normal state.43

Mirror therapy is advantageous in terms of patient education and preparation, individual setup, face-to- face guidance, and reassessment.41 Sex also exhibits a relationship with its benefits.31 The intensity of mirror therapy affects its effectiveness in pain alleviation,34 although contradictory findings have been reported.26 Evidence regarding its efficacy remains low to moderate.38,39 Low- intensity mirror therapy has shown no significant outcome differences compared with non-mirror interventions and is therefore considered ineffective.27,31

Future studies should investigate intermediate variables in mirror therapy to identify factors that may enhance or diminish its benefits. Conflicting findings regarding the efficacy of mirror therapy warrant further studies to determine whether variables such as patient education affect efficacy. Additionally, increased intensity might enhance its effectiveness. One potential approach could involve incorporating VR or AR technology, which may simplify therapy.

Virtual/augmented reality therapies

VR and AR facilitate integration of psychotherapies while increasing accessibility, particularly with mirror therapy.31,40,50 Various training exercises have been facilitated by VR/AR including motor training42,54 and imagery training.42 The application of VR has demonstrated effects similar to those of conventional psychotherapies,40 and some evidence suggests superior efficacy. VR/AR systems are advantageous not only because they can implement conventional psychotherapies in a standardised manner but also because they enable automatic assessment of parameters for tracking performance and compliance.42 VR facilitates visualisation in relation to individually matched phantom limbs.51 VR/AR overcome limitations in plasticity-based approaches such as conventional mirror therapy, which may otherwise hinder effectiveness.50 VR/AR enhance efficacy, procedural accuracy, and assessment processes while serving as a platform for the integration of multiple psychotherapies.

VR is particularly suitable for visual applications and may be recommended in conjunction with EMDR. The use of EMDR-VR for PLP warrants further investigation. VR mirror therapy may enhance patient engagement. VR technology offers greater flexibility and control, potentially increasing the intensity and effectiveness of mirror therapy.

Combinations of psychotherapies

The most commonly used modality for combination is mirror therapy,29,30,33,40,42,44 followed by VR/AR therapy40,42 and muscle relaxation.73,74 Combined modalities have demonstrated significantly greater effectiveness than single therapies, especially mirror therapy or training. Although mirror therapy is often effective, it remains a limited sensory approach in which the patient perceives an imaginary movement of the amputated body part as if it were moving normally through the reflection of a mirror.85

The combination of virtual feedback, motor imagery, and auditory feedback enhances the efficacy of mirror therapy by providing multiple congruent sensory stimuli in the overall perceptual process. Combinations with VR enhance the effect by standardising training procedures and facilitating assessments of performance and compliance.42,44 However, one study revealed that only one in four participants showed improvement across all measures, whereas other participants exhibited no improvement. Notably, one participant experienced recurrent pain.56 These findings highlight the importance of individual differences in therapy outcomes, particularly in relation to the patient’s commitment to therapy. PLP may be a multidimensional disorder. Combination therapy can address limitations in individual therapies that specialise in a particular area of improvement.

Limitations

This review had some limitations. Biases were not assessed in each included study. Case reports included were heterogeneous with regard to sex, age, amputated limbs, and therapists.

Conclusion

PLP is a complex condition encompassing physiological, psychological, and social factors. Due to its biopsychosocial nature, pharmacological treatments alone provide limited relief. Psychotherapeutic modalities have demonstrated effectiveness in treating PLP. Mirror therapy and VR/AR are among the most commonly used modalities. The combined use of multiple psychotherapeutic modalities is more beneficial than standalone approaches.

Contributors

All authors designed the study and analysed the data. RRG, HH, and GB acquired the data. RRG drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr Andrian Liem for his valuable input.

References

- Furukawa T. Charles Bell’s description of the phantom phenomenon in 1830. Neurology 1990;40:1830. Crossref

- Kaur A, Guan Y. Phantom limb pain: a literature review. Chin J Traumatol 2018;21:366-8. Crossref

- Weinstein SM. Phantom limb pain and related disorders. Neurol Clin 1998;16:919-36. Crossref

- Limakatso K, Bedwell GJ, Madden VJ, Parker R. The prevalence and risk factors for phantom limb pain in people with amputations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2020;15:e0240431. Crossref

- Smith HS. Potential analgesic mechanisms of acetaminophen. Pain Physician 2009;12:269-80. Crossref

- Cascella M, Forte CA, Bimonte S, et al. Multiple effectiveness aspects of tapentadol for moderate-severe cancer-pain treatment: an observational prospective study. J Pain Res 2018;12:117-25. Crossref

- O’Connor AB, Dworkin RH. Treatment of neuropathic pain: an overview of recent guidelines. Am J Med 2009;122(10 Suppl):S22-S32. Crossref

- Robinson LR, Czerniecki JM, Ehde DM, et al. Trial of amitriptyline for relief of pain in amputees: results of a randomized controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:1-6. Crossref

- Hsu E, Cohen SP. Postamputation pain: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. J Pain Res 2013;6:121-36. Crossref

- Alviar MJ, Hale T, Dungca M. Pharmacologic interventions for treating phantom limb pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;10:CD006380. Crossref

- McCormick Z, Chang-Chien G, Marshall B, Huang M, Harden RN. Phantom limb pain: a systematic neuroanatomical-based review of pharmacologic treatment. Pain Med 2014;15:292-305. Crossref

- Kern KU, Baust H, Hofmann W, Holzmüller R, Maihöfner C, Heskamp ML. Capsaicin 8 % cutaneous patches for phantom limb pain. Results from everyday practice (non-interventional study) [in German]. Schmerz 2014;28:374-83. Crossref

- Casale R, Ceccherelli F, Labeeb AA, Biella GE. Phantom limb pain relief by contralateral myofascial injection with local anaesthetic in a placebo-controlled study: preliminary results. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:418-22. Crossref

- Sturgeon JA. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2014;7:115-24. Crossref

- Aguilera-Martín Á, Gálvez-Lara M, Cuadrado F, et al. Cost- effectiveness and cost-utility evaluation of individual vs. group transdiagnostic psychological treatment for emotional disorders in primary care (PsicAP-Costs): a multicentre randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Psychiatry 2022;22:99. Crossref

- Kröner-Herwig B. Chronic pain syndromes and their treatment by psychological interventions. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2009;22:200-4 Crossref

- Finn SB, Perry BN, Clasing JE, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of mirror therapy for upper extremity phantom limb pain in male amputees. Front Neurol 2017;8:267. Crossref

- Ortiz-Catalan M, Sander N, Kristoffersen MB, Håkansson B, Brånemark R. Treatment of phantom limb pain (PLP) based on augmented reality and gaming controlled by myoelectric pattern recognition: a case study of a chronic PLP patient. Front Neurosci 2014;8:24. Crossref

- Page DM, George JA, Kluger DT, et al. Motor control and sensory feedback enhance prosthesis embodiment and reduce phantom pain after long-term hand amputation. Front Hum Neurosci 2018;12:352. Crossref

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467-73. Crossref

- Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement 2021;19:3-10. Crossref

- Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI;2024Crossref

- Munn Z, Stone JC, Aromataris E, et al. Assessing the risk of bias of quantitative analytical studies: introducing the vision for critical appraisal within JBI systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synth 2023;21:467-71.Crossref

- Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:132-40. Crossref

- McArthur A, Klugarová J, Yan H, Florescu S. Chapter 4: Systematic Reviews of Text and Opinion. In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis;2020Crossref

- Xie HM, Zhang KX, Wang S, et al. Effectiveness of mirror therapy for phantom limb pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2022;103:988-97. Crossref

- Wareham AP, Sparkes V. Effect of one session of mirror therapy on phantom limb pain and recognition of limb laterality in military traumatic lower limb amputees: a pilot study. BMJ Mil Health 2020;166:146-50. Crossref

- Chan AW, Bilger E, Griffin S, et al. Visual responsiveness in sensorimotor cortex is increased following amputation and reduced after mirror therapy. Neuroimage Clin 2019;23:101882. Crossref

- Ol HS, Van Heng Y, Danielsson L, Husum H. Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia. Scand J Pain 2018;18:603-10. Crossref

- DeMoss P, Ramsey LH, Karlson CW. Phantom limb pain in pediatric oncology. Front Neurol 2018;9:219. Crossref

- Rothgangel A, Braun S, Winkens B, Beurskens A, Smeets R. Traditional and augmented reality mirror therapy for patients with chronic phantom limb pain (PACT study): results of a three-group, multicentre single-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2018;32:1591-608. Crossref

- Ramachandran V, Chunharas C, Marcus Z, Furnish T, Lin A. Relief from intractable phantom pain by combining psilocybin and mirror visual-feedback (MVF). Neurocase 2018;24:105-10. Crossref

- Herrador Colmenero L, Perez Marmol JM, Martí-García C, et al. Effectiveness of mirror therapy, motor imagery, and virtual feedback on phantom limb pain following amputation: a systematic review. Prosthet Orthot Int 2018;42:288-98. Crossref

- Imaizumi S, Asai T, Koyama S. Agency over phantom limb enhanced by short-term mirror therapy. Front Hum Neurosci 2017;11:483. Crossref

- Cárdenas K, Aranda M. Psychotherapies for the treatment of phantom limb pain [in Spanish]. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr 2017;46:178-86. Crossref

- Franz EA, Fu Y, Moore M, et al. Fooling the brain by mirroring the hand: brain correlates of the perceptual capture of limb ownership. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2016;34:721-32. Crossref

- Guenther K. ‘It’s All Done With Mirrors’: V.S. Ramachandran and the material culture of phantom limb research. Med Hist 2016;60:342-58. Crossref

- Barbin J, Seetha V, Casillas JM, Paysant J, Pérennou D. The effects of mirror therapy on pain and motor control of phantom limb in amputees: a systematic review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2016;59:270-5. Crossref

- Rothgangel A, Braun S, de Witte L, Beurskens A, Smeets R. Development of a clinical framework for mirror therapy in patients with phantom limb pain: an evidence-based practice approach. Pain Pract 2016;16:422-34. Crossref

- Diers M, Kamping S, Kirsch P, et al. Illusion-related brain activations: a new virtual reality mirror box system for use during functional magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Res 2015;1594:173-82. Crossref

- Hagenberg A, Carpenter C. Mirror visual feedback for phantom pain: international experience on modalities and adverse effects discussed by an expert panel: a delphi study. PM R 2014;6:708-15. Crossref

- Trojan J, Diers M, Fuchs X, et al. An augmented reality home-training system based on the mirror training and imagery approach. Behav Res Methods 2014;46:634-40. Crossref

- Foell J, Bekrater-Bodmann R, Diers M, Flor H. Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain: brain changes and the role of body representation. Eur J Pain 2014;18:729-39. Crossref

- Wilcher DG, Chernev I, Yan K. Combined mirror visual and auditory feedback therapy for upper limb phantom pain: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2011;5:41. Crossref

- Seidel S, Kasprian G, Furtner J, et al. Mirror therapy in lower limb amputees—a look beyond primary motor cortex reorganization. Rofo 2011;183:1051-7. Crossref

- Diers M, Christmann C, Koeppe C, Ruf M, Flor H. Mirrored, imagined and executed movements differentially activate sensorimotor cortex in amputees with and without phantom limb pain. Pain 2010;149:296-304. Crossref

- Casale R, Damiani C, Rosati V. Mirror therapy in the rehabilitation of lower-limb amputation: are there any contraindications? Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2009;88:837-42. Crossref

- Ramachandran VS, Brang D, McGeoch PD. Size reduction using mirror visual feedback (MVF) reduces phantom pain. Neurocase 2009;15:357-60. Crossref

- Sumitani M, Miyauchi S, McCabe CS, et al. Mirror visual feedback alleviates deafferentation pain, depending on qualitative aspects of the pain: a preliminary report. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1038-43. Crossref

- Hoffman HG, Boe DA, Rombokas E, et al. Virtual reality hand therapy: a new tool for nonopioid analgesia for acute procedural pain, hand rehabilitation, and VR embodiment therapy for phantom limb pain. J Hand Ther 2020;33:254-62. Crossref

- Thøgersen M, Andoh J, Milde C, Graven-Nielsen T, Flor H, Petrini L. Individualized augmented reality training reduces phantom pain and cortical reorganization in amputees: a proof of concept study. J Pain 2020;21:1257-69. Crossref

- Rutledge T, Velez D, Depp C, et al. A virtual reality intervention for the treatment of phantom limb pain: development and feasibility results. Pain Med 2019;20:2051-9. Crossref

- Dunn J, Yeo E, Moghaddampour P, Chau B, Humbert S. Virtual and augmented reality in the treatment of phantom limb pain: a literature review. NeuroRehabilitation 2017;40:595-601. Crossref

- Perry BN, Mercier C, Pettifer SR, Cole J, Tsao JW. Virtual reality therapies for phantom limb pain. Eur J Pain 2014;18:897-9. Crossref

- Saruco E, Guillot A, Saimpont A, et al. Motor imagery ability of patients with lower-limb amputation: exploring the course of rehabilitation effects. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2019;55:634-45. Crossref

- McAvinue LP, Robertson IH. Individual differences in response to phantom limb movement therapy. Disabil Rehabil 2011;33:2186-95. Crossref

- Beaumont G, Mercier C, Michon PE, Malouin F, Jackson PL. Decreasing phantom limb pain through observation of action and imagery: a case series. Pain Med 2011;12:289-99. Crossref

- Oakley DA, Whitman LG, Halligan PW. Hypnotic imagery as a treatment for phantom limb pain: two case reports and a review. Clin Rehabil 2002;16:368-77. Crossref

- Rosén G, Willoch F, Bartenstein P, Berner N, Røsjø S. Neurophysiological processes underlying the phantom limb pain experience and the use of hypnosis in its clinical management: an intensive examination of two patients. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2001;49:38-55. Crossref

- Muraoka M, Komiyama H, Hosoi M, Mine K, Kubo C. Psychosomatic treatment of phantom limb pain with post-traumatic stress disorder: a case report. Pain 1996;66:385-8. Crossref

- Siegel EF. Control of phantom limb pain by hypnosis. Am J Clin Hypn 1979;21:285-6. Crossref

- Schneider J, Hofmann A, Rost C, Shapiro F. EMDR in the treatment of chronic phantom limb pain. Pain Med 2008;9:76-82. Crossref

- Silver SM, Rogers S, Russell M. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in the treatment of war veterans. J Clin Psychol 2008;64:947-57. Crossref

- de Roos C, Veenstra AC, de Jongh A, et al. Treatment of chronic phantom limb pain using a trauma-focused psychological approach. Pain Res Manag 2010;15:65-71. Crossref

- Limakatso K, Madden VJ, Manie S, Parker R. The effectiveness of graded motor imagery for reducing phantom limb pain in amputees: a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2020;109:65-74. Crossref

- Moseley GL. Graded motor imagery for pathologic pain: a randomised controlled trial. Neurology 2006;67:2129-34. Crossref

- Mercier C, Sirigu A. Training with virtual visual feedback to alleviate phantom limb pain. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009;23:587-94. Crossref

- Dougherty J. Relief of phantom limb pain after EMG biofeedback- assisted relaxation: a case report. Behav Res Ther 1980;18:355-7. Crossref

- Sherman RA, Gall N, Gormly J. Treatment of phantom limb pain with muscular relaxation training to disrupt the pain-anxiety-tension cycle. Pain 1979;6:47-55. Crossref

- Meyer P, Matthes C, Kusche KE, Maurer K. Imaginative resonance training (IRT) achieves elimination of amputees’ phantom pain (PLP) coupled with a spontaneous in-depth proprioception of a restored limb as a marker for permanence and supported by pre-post functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Psychiatry Res 2012;202:175-9. Crossref

- Pereira L, Noronha D, Bishop A. Cognitive behavioral therapy for postamputation chronic pain: a case report. Cogn Behav Pract 2023;30:160-8. Crossref

- Yanagisawa T, Fukuma R, Seymour B, et al. Neurofeedback training without explicit phantom hand movements and hand-like visual feedback to modulate pain: a randomized crossover feasibility trial. J Pain 2022;23:2080-91. Crossref

- Belleggia G, Birbaumer N. Treatment of phantom limb pain with combined EMG and thermal biofeedback: a case report. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2001;26:141-6. Crossref

- Brunelli S, Morone G, Iosa M, et al. Efficacy of progressive muscle relaxation, mental imagery, and phantom exercise training on phantom limb: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:181-7. Crossref

- MacIver K, Lloyd DM, Kelly S, Roberts N, Nurmikko T. Phantom limb pain, cortical reorganization and the therapeutic effect of mental imagery. Brain 2008;131:2181-91. Crossref

- Howard DL. Group therapy for amputees in a ward setting. Mil Med 1983;148:678-80. Crossref

- Ulger O, Topuz S, Bayramlar K, Sener G, Erbahçeci F. Effectiveness of phantom exercises for phantom limb pain: a pilot study. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:582-4. Crossref

- Schmalzl L, Ragnö C, Ehrsson HH. An alternative to traditional mirror therapy: illusory touch can reduce phantom pain when illusory movement does not. Clin J Pain 2013;29:e10-e18. Crossref

- Blood AM. Psychotherapy of phantom limb pain in two patients. Psychiatr Q 1956;30:114-22. Crossref

- Niraj S, Niraj G. Phantom limb pain and its psychologic management: a critical review. Pain Manag Nurs 2014;15:349-64. Crossref

- Kim SY, Kim YY. Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain. Korean J Pain 2012;25:272-4. Crossref

- McCabe CS, Haigh RC, Blake DR. Mirror visual feedback for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome (type 1). Curr Pain Headache Rep 2008;12:103-7. Crossref

- Priganc VW, Stralka SW. Graded Motor Imagery. J Hand Ther 2011;24:164-9. Crossref

- Thieme H, Morkisch N, Mehrholz J, et al. Mirror therapy for improving motor function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;7:CD008449. Crossref

- Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D. Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors. Proc Biol Sci 1996;263:377-86. Crossref