East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018;28:159-73 | DOI: 10.12809/eaap1835

THEME PAPER

Alan R Felthous, MD, Forensic Psychiatry Division, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA.

Je Ko, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA.

Address for correspondence: Prof Alan R Felthous, Forensic Psychiatry Division, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, 1438 South Grand Blvd., Saint Louis, Missouri, USA 63104.

Tel: 1 (314) 977 4826; Fax: 1 (314) 977 4876; Email: alan.felthous@health.slu.edu

Submitted: 9 April 2018; Accepted: 5 July 2018

Abstract

Sexually violent predator (SVP) laws in the United States are controversial. They tend to be opposed by academics, libertarians, and professional organisations but are supported by states and the Supreme Court. This study reviews the history of SVP legislation, compares features of SVP laws among states, and summarise requirements by the Supreme Court that shaped these laws. Features of SVP laws include identification of sexual offenders with mental abnormality that predisposes them to sexually offending behaviours in the future, and standards of proof for conditional or unconditional release. A comprehensive understanding of all statutes can inform policymakers about SVP laws, whether supportive or restrictive of such legislation.

Key words: Commitment of mentally ill; Legislation and jurisprudence; Sex offenses

Introduction

This study reviews the history of sexually violent predator (SVP) laws in the United States, compares features of SVP laws among states, and summarises requirements by the Supreme Court that shaped these laws. Criticisms and justifications regarding contemporary SVP laws are discussed.

History

In early Ecclesiastical and Anglo-American common law, adultery, swearing desperate oaths, blasphemy, buggery (anal intercourse) with one’s wife,1 and fornication2 were subjected to physical punishments such as public whippings. These behaviours are not considered criminal today. The level of physical punishment depended upon the era and the jurisdiction. The purposes of punishment then were primary deterrence (to disincentivise the offender from repeating the offence) and secondary deterrence (to deter the public by example).1 Atonement or expiation was also a purpose when laws of morality were supported with religious doctrine.

Prior to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, the crime and punishment of rape against a woman depended upon whether she was a ‘propertied virgin’. The crime was considered more serious because it was against an estate, not simply against a woman or her body.1,3 Rapists of this class of women were subjected to death and dismemberment, including excision of the scrotum. The tails of the rapist’s dogs and horses were also subjected to dismemberment.1 Although the female victim could spare her assailant from execution by marrying him, ownership of his money and land would be transferred to her.1

After the Norman Conquest, trial by combat replaced ordeal, yet punishments remained severe and included castration and blinding. If the sexually assaulted woman lacked a champion to fight on her behalf, the accused was acquitted.1 Rape of non-virgins and unpropertied virgins was considered less serious and handled by manorial courts (rather than the Crown), with lesser punishments that did not include dismemberment.1

By the end of the 13th century, the Statutes of Westminster extended the jurisdiction of the Crown to include forcible rape of all women.1 Marriage no longer spared the assailant, statutory rape of minors became an offence, and rape was made a public offence. Rape was a felony punishable by imprisonment or death.

Such laws and punishments came to the American colonies where rape was the first law for which a ‘warrant for this penalty in the Holy Scriptures’ was not required (other sexual offences such as fornication, adultery, bestiality, and buggery were biblically forbidden).1 Statutory rape could be punished by death, and rape of a minor was punished with lashings, slitting the nostrils, and wearing a neck halter in public.1

Until 1805 the laws based upon biblical injunction were punishable by death.1 In the 19th and 20th centuries, state laws codified criminal acts, including sexually offending acts, replacing common law. Sexual offenders were imprisoned and sometimes executed, but no longer subjected to dismemberment, mutilation, and public whippings. Rehabilitation programmes were provided in some state prison systems, but participation was voluntary and the programmes typically ended at the end of the sentence. If the main penological objectives before codification and imprisonment were primary and secondary deterrence, imprisonment served primarily incapacitation.

In the 20th century, brutal sexual offences by offenders who had not been charged or who had been imprisoned then released shocked the community. In response to high-profile sexual crimes,4 (some) involving killing the victims,5 states began enacting sexual psychopath laws in the late 1930s,6,7 with Michigan being the first in 1937. By 1949, 12 states and the District of Columbia enacted sexual psychopath laws.8 Such enactments peaked in the mid-1960s when more than half of the states enacted the laws to provide legal and medical treatment for offenders with abnormal, sexual criminal behaviour.1,9 The purposes were to protect the community and to treat/habilitate sexual offenders.6,9

According to the American Bar Association Criminal Justice Mental Health Standards,7 sexual psychopath laws were based on six assumptions: (1) there is a mental disability known as sexual psychopathy, psychopathy, or defective delinquent; (2) persons with such a disability are more likely to commit serious crimes, especially dangerous sexual offences, than normal criminals; (3) such persons are easily identified by mental health professionals; (4) the dangerousness of these offenders can be predicted by mental health professionals; (5) treatment is available for the condition; and (6) large numbers of persons afflicted with such disabilities can be cured. However, sexual psychopath laws were criticised to be in violation of the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the US Constitution.7 In the 1980s, many states repealed the sexual psychopath laws. Legislation of fixed sentences was aimed at reducing the risk of early prison release. Nonetheless, at the end of the sentence, the offender was released and the criminal justice system no longer had physical control of the offender for rehabilitative or preventive purposes. In the early 1990s, horrific, brutal sexual offences, sometimes victimising young children, led to the enactment of sexual predator laws.

SVP laws in the United States

In the 1990s, SVP laws were enacted in response to heinous sexual crimes committed by offenders recently released from prison. The first was the Washington’s Community Protection Act of 1990. As of 2018, similar statutes for civil commitment of repeat child-victimising sex offenders were enacted in 21 other states (Fig 1). The SVP or sexually dangerous person (SDP) laws attempt to ‘control, care, and treat’ certain sexual offenders through civil confinement

and involuntary treatment until the offenders no longer pose a danger to society. These laws emphasised on treatment and were repeatedly found constitutional by the Supreme Court. The central elements of the SVP laws are: (1) legal authority for continuing to detain sexual offenders with mental disorders who are already in custody and likely to re-offend if released; and (2) continued confinement via civil commitment to a treatment facility.10 The commitment requires proof of four conditions: (1) one or more charges (if found not guilty by reason of insanity or incompetent to stand trial) or convictions of a sexually violent offence, (2) a qualifying mental abnormality, (3) a specified likelihood of engaging in further acts of predatory sexual violence, and (4) a causal link between the mental abnormality and the risk of recidivism.10

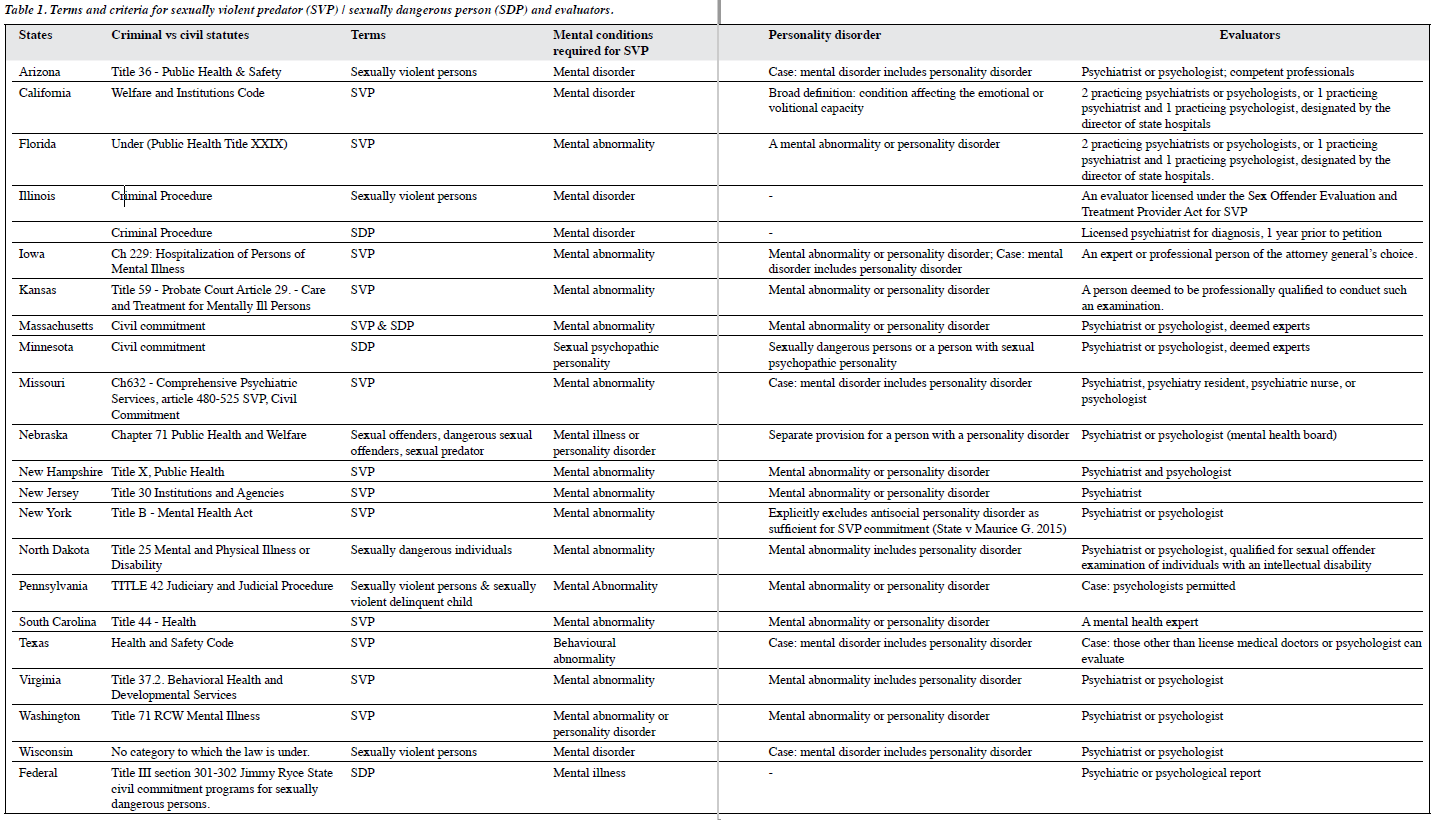

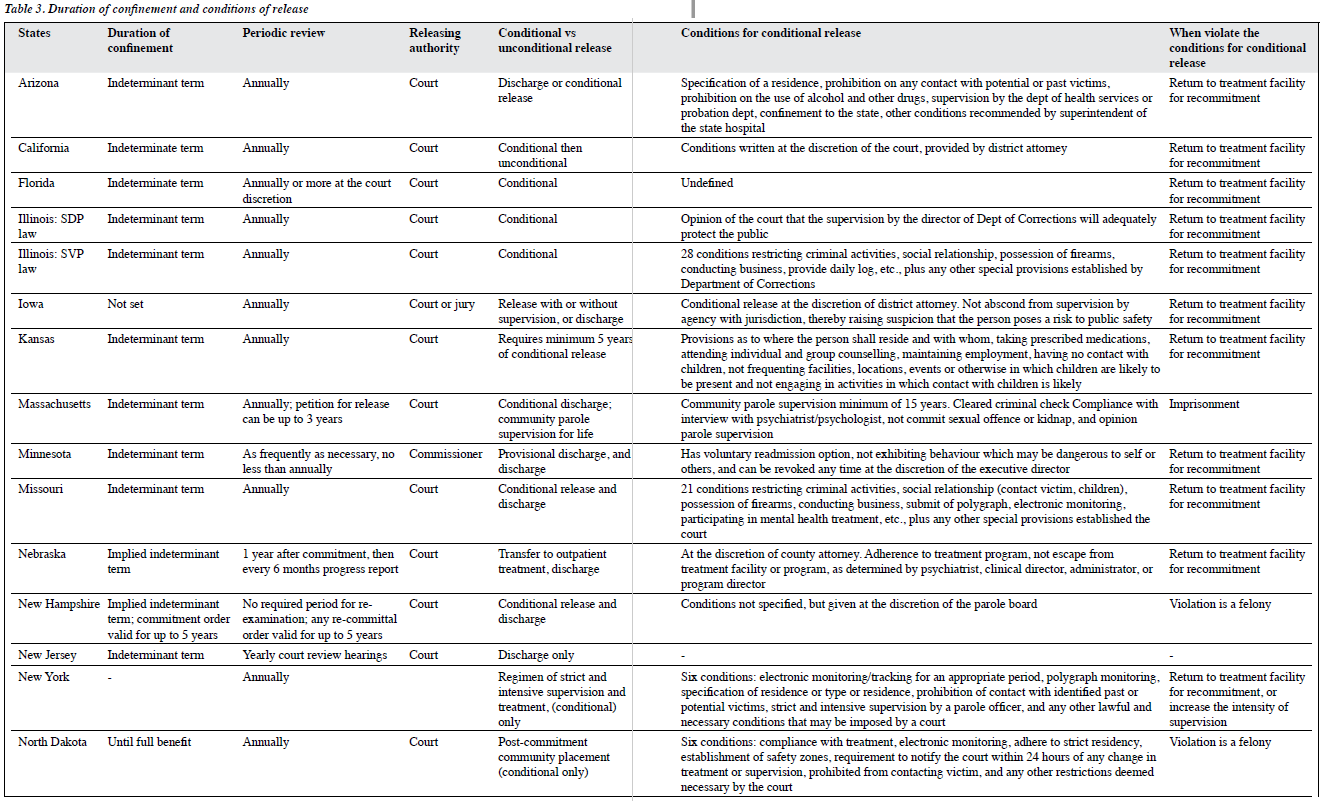

Features of SVP laws in each state were compiled based on three studies.11-13 Table 1 shows laws and criteria for SVP/SDP and evaluators. Table 2 shows procedures of SVP law that require probable cause hearing, burden and standards of proof for commitment and release, and option for a jury trial. Table 3 shows the duration of confinement, periodic review requirement, and conditional and unconditional release.

Most states define SVP as any person who has been convicted of or charged with a crime of sexual violence and has a mental abnormality or personality disorder that makes the person likely to engage in predatory acts of sexual violence if not confined in a secure facility. After psychological evaluation of the SVP, the department of corrections and the department of mental health refer their findings to the attorney general who then files a petition to civilly commit the SVP. Once committed, the SVP is detained until the cognizant court conducts a probable cause hearing, and a trial follows after probable cause is found by the judge.

The SVP laws were reviewed in terms of: (1) whether the statutes are criminal or civil, (2) definitions of SVP, (3)

definitions of mental abnormality and whether personality disorder is included, (4) standard of proof for commitment in comparison with that for release, (5) duration of commitment and whether periodic review is required, (6) types of evaluators, and (7) release procedures and whether statutes provide for conditional release (and consequences for violating the conditions).

Whether the statutes are criminal or civil

Some states place the SVP statute under criminal chapters but specify that the involuntary commitment is civil; the criminal title pertains to the criminal acts only. Wisconsin has a separate chapter for SVP (separate from the state Sex Crimes Law). Other states place SVP laws under titles relating to public health, state health, hospitalisation of persons of mental illness, care and treatment for mentally ill persons, public welfare, comprehensive psychiatric services, public health and welfare, mental health act, mental and physical illness or disability, health, health and safety code, behavioural health and developmental services, and mental illness.

Definitions of SVP

Some states use the term SVP; others use less stigmatising terms (sexually violent person, SDP, sexually dangerous individual). The term ‘SVP’ has a determinative and animalistic quality, whereas ‘SDP’ simply describes the offending behaviour.11 Nebraska differentiates sexual offender from sexual predator who has a high risk of recidivism and has victimised a person aged 18 years or younger. Massachusetts changed the term from SVP to SDP in 1998 and added the condition ‘if not confined to a secure facility’ to the likelihood of engaging in sexual offences.

Illinois has separate statutes for SDP and sexually violent persons. SDP is defined as “all persons suffering from a mental disorder… coupled with criminal propensities to the commission of sex offences and who have demonstrated propensities towards acts of sexual assault or acts of sexual molestation of children”.12 The Illinois SDP Act allows a parallel prosecution action that a state attorney may file instead of charging the person with a sexual offence. The SDP is then committed to the state hospital, in lieu of the department of corrections and is provided sexual offender treatment.12 The Illinois SDP Act allows those who have already been diagnosed with a mental disorder (by a licensed psychiatrist) and who have been charged with a sexual offence to have the option of being committed directly to a state hospital without being tried for a sexual offence.

In Illinois, ‘sexually violent person’ refers to an already convicted sexual offender who is committed to the department of human services for care and treatment after having served his/her sentence in the department of corrections.13 The term ‘SDP’ refers to an offender with a prior diagnosis of a mental disorder at least 1 year prior to the filling of the petition. In contrast, for an offender to be termed ‘SVP’ requires a separate evaluation by an evaluator licensed under the Sex Offender Evaluation and Treatment Provider Act13 if the offender should be subjected to such commitment after the sentence has been served.

Definitions of mental abnormality and whether personality disorder is included

Although no state explicitly allows incompetence to stand trial or the insanity defence to be determined by personality disorder alone as the qualifying mental condition, SVP laws allow commitment of individuals when recidivism is likely to occur from any mental condition, including personality disorder (often antisocial personality disorder). Most states use the terms ‘mental disorder’, ‘mental abnormality’, ‘behavioural abnormality’, and ‘mental illness’. Minnesota uses ‘sexual psychopathic personality’, which means “the existence in any person of such conditions of emotional instability, or impulsiveness of behaviour, or lack of customary standards of good judgment, or failure to appreciate the consequences of personal acts, or a combination of any of these conditions, which render the person irresponsible for personal conduct with respect to sexual matters, if the person has evidenced, by a habitual course of misconduct in sexual matters, an utter lack of power to control the person’s sexual impulses and, as a result, is dangerous to other persons.”

Standards of proof for commitment and release

The burden of proof to determine an SVP is always on the state, based on the evidence from qualified professionals. The standard of proof for committing an SVP differs among states. Some states require that evidence to establish an SVP is beyond a reasonable doubt; others require a lower standard of clear and convincing evidence. Some states add ‘indefinite term’ for the duration of civil commitment; others do not mention the duration but imply an indeterminate term. All states provide the condition that commitment lasts until the mental abnormality no longer causes the person to be a threat to others, except for Pennsylvania where the court orders a 1-year waiting period. The state is required to provide clear and convincing evidence that the person continues to have serious difficulty controlling sexually violent behaviour while committed for inpatient treatment. If this standard is met, the court will order an additional period of involuntary inpatient treatment of 1 year.

The standard of proof for releasing an SVP also varies by state, although it is usually the same as that for initial commitment. The conditions for release are usually equivalent to those for commitment. Exceptions are Illinois and Massachusetts where the standards of proof for release are lower than standards of conviction. New Jersey does not specify a standard of proof but listens to the recommendation of the treatment team in the petition for (conditional) release.

There is no uniformity in the initial procedure for releasing the committed person or for petitioning for the release of the convicted person.

Duration of commitment and periodic review

All states explicitly or implicitly indicate indeterminate commitment of SVP, except for Pennsylvania stating 1 year and annual renewal. All other states require a periodic review of the SVP condition and likelihood for recidivism or dangerousness to the society. Most require annual review and report to the court. New Jersey requires an annual court review hearing. Florida and Minnesota allow more frequent reviews under the discretion of the court. Minnesota did not initially include a mandate for a periodic review, and an amendment was added in 2017. Nebraska requires a 6-month periodic progress report after the first annual post-commitment report. New Hampshire, New York, and Virginia have no required period for re-examination. In New Hampshire, if the offender fails to obtain a grant to be released, any recommittal order shall be valid for up to 5 years. New York allows for up to yearly petitions for release. New Jersey requires an annual court review hearing, in addition to a formal report. Texas requires review only every 2 years.

Types of evaluators

As early as 72 hours into incarceration, or as late as 1 month before anticipated release, the convicted sexual offender will have a review set by the attorney general or the state attorney who initiates a petition for SVP commitment once the offender has served the prison sentence. The petition is followed by a notice to the convicted sexual offender before the anticipated release. The offender is evaluated by a licensed professional (appointed by the attorney general, the court, or the director of state hospitals) or a generic psychiatrist or psychologist deemed expert. Missouri also recognises nurses and psychiatry residents as designated professionals. New Jersey allows only a licensed psychiatrist. In one case in Texas, someone other than a licensed medical doctor or psychologist evaluated an SVP.14

Whether statutes provide conditional release

The release of an SVP can be conditional or unconditional. In New Jersey, once an SVP is deemed unlikely to engage in acts of sexual violence by the treatment team, the SVP can be discharged, with any conditions cited in the statute. When an SVP has shown improvement in condition (and the petition is granted), some states allow conditional release (typically to a less restrictive environment at the discretion and recommendation of the treatment facility). The conditions for sustaining the release from inpatient commitment (except Texas where restrictive supervised residency is provided) vary among states. Some states allow the supervising director, department, or court to impose conditions at their discretion. Others have strict conditions specified from a single mention of continued outpatient treatment or require compliance with a sexual offender registry. Minnesota provides the offender the option of voluntary readmission to the inpatient treatment. In most states, the SVP returns to the treatment facility for recommitment. New York has an additional provision to increase the intensity of supervision. Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and North Dakota consider a violation of conditions for conditional release as a felony, resulting in a prison sentence.

Supreme Court decisions

Pre-SVP decisions

In 1967, the United States Supreme Court found the Colorado law to be unconstitutional in Specht v. Patterson.15 Specht was convicted of a sexual offence in Colorado and was sentenced to detention for an indefinite term of up to life under the Sex Offenders Act, which provided for such a sentence when a person who was convicted of a sex offense was either a “mentally ill habitual offender” or represented a “threat of bodily harm to the public.” This finding was based only on a psychiatric report that his condition was treatable. This procedure was approved by the Colorado Supreme Court.

However, the United State Supreme Court held that the procedure was unconstitutional because it violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, which states: “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunity of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due process of law, nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The Fourteenth Amendment was originally intended to ensure that freed African-American slaves would enjoy the same rights as other citizens following the Civil War, and to negate the slavery supporting Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford.16 The Fourteenth Amendment became the basis for most decisions that provided rights for persons with mental illness, particularly the Due Process Clause, Equal Protection Clause, and the right to liberty.

The Supreme Court reasoned that the Colorado Sex Offenders Act allowed imposition of an indeterminate sentence without a trial with a new finding of fact. Specht was subject to this commitment based only upon his prior conviction of a crime for which he had already served his sentence. Such a ‘new sentence’ would require a new finding of fact, essentially a criminal-like proceeding with full rights to due process, such as the rights to a hearing and to counsel, to confront witnesses, to cross examine witnesses, and to present evidence in one’s self defence.

Nonetheless, in Allen v. Illinois in 1986, the Supreme Court revived the possibility of indefinite commitment of sexual offenders.17 Illinois petitioned to have Terry Allen, who was charged with a sexual offence, declared an SDP under the Illinois Sexually Dangerous Persons Act. Allen claimed violation of his Fifth Amendment privileges against self-incrimination when two psychiatrists supported his commitment by testifying in court that he was mentally ill and had a propensity to commit further sexual crimes.

The Fifth Amendment provides several rights or privileges for citizens accused of criminal offence, including the privilege against self-incrimination or the ‘right to remain silent’, as follows: “No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

The Supreme Court held that the commitment proceedings were intended to provide treatment, not punishment, and therefore were essentially civil in nature. If Allen could refuse psychiatric interviews, the state’s interests in protecting the public and providing Allen with treatment would be blocked. The Fifth Amendment is a privilege against testifying against oneself in criminal prosecution, not civil commitment, thus the Court concluded US Sexually Violent Predator Law that proceedings under Illinois Sexually Dangerous Persons Act were civil and did not afford Allen the privilege against self-incrimination. The Act required proof of mental disorder and dangerousness, consistent with civil commitment proceedings. The committed person can apply for his release anytime based upon his proving that he is no longer dangerous.

However, four justices dissented, pointing out features of the proceedings that are more criminal than civil. In addition, Illinois civil commitment law provides the individual a right to remain silent. The Act is unlike both the state’s mental health code and the code of criminal procedure in denying the individual the right to remain silent.

Nonetheless, the Supreme Court upheld the Act’s constitutionality and opened the door for enactment of SVP laws that would follow. Illinois became one of the states to have both SVP and SDP laws. Some defendants may negotiate for an SDP commitment as a more favourable alternative to felony conviction and the risk of eventual SVP commitment.

The Supreme Court decision set the condition for states to enact SVP laws, delineating what features of such laws would render them constitutional. Once SVP laws were enacted, they came under constitutional challenges that led to further parameters and refinements. These cases also collectively supported SVP laws ensuring their continued existence. We extracted some landmark cases that support or limit SVP legislation and that correspond with features of SVP laws.

It seems that rehabilitation ought to be initiated during imprisonment, even apart from the question of whether the lack thereof would render the therapeutic claim of SVP legislation to be meretricious. If sexual offender treatment programmes are incorporated into the prison system, to what extent should participation in the programme and compliance with its treatment requirements be voluntary, compelled, or encouraged with incentives or disincentives? After Kansas v. Hendricks,18 Kansas established a sexual offender treatment programme through its Sexual Abuse Treatment Program Act. This was subject to constitutional challenge; the core issue concerned the matter of voluntariness versus compulsion.

Post-SVP decisions

The Supreme Court has both supported and restrained the development of SVP laws. Paraphilia can be qualified to be a mental abnormality or a personality disorder. Antisocial personality disorder may be qualified to be a personality disorder,18 but antisocial personality may not. The personality disorder is on firmer ground if it is explicitly a disorder. In any event the commitment and detention must be based upon presence of the same disorder for which the commitment was proposed and its presence must be proven at the commitment hearing.19 Even though ordinary commitment laws require presence of “mental illness”, a legal term not to be found in DSM-5, mental illness is not required for SVP commitment. In fact, no particular terminology is required to further designate the mental abnormality. Neither is there a requirement for the mental abnormality to be amenable to treatment and improvement. Regarding dangerousness, there must have been a recent overt act of sexual dangerousness prior to the initial detention under the SVP law. A person whose sexually offending behaviour occurred long before and who continued to live in the community without engaging in such conduct may not qualify for SVP commitment.19 Importantly there must be a causal nexus between the mental abnormality or personality disorder and the person’s sexual dangerousness, such that the condition diminishes the person’s ability to control his sexually offending behaviour. The condition should cause serious difficulty in controlling the person’s proclivity towards sexual offences, but this lack of control need not be total or absolute.

SVP laws are not unconstitutional or in violation of double jeopardy or ex post facto prohibitions, even when the person has already been convicted and served his sentence for the index sexual offence.18 This is because SVP laws are civil so the double jeopardy and ex post facto prohibitions in criminal procedures do not apply. The initial hearing must be within 72 hours of the commitment. The SVP laws require that the essential elements for establishing an SVP must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.19 States have to consider first whether restriction as an SVP is the least restrictive treatment, as required by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.19

For an SVP law to be civil, not criminal in nature, its purpose must be treatment, not punishment in the sense of retribution. An effort must be made to treat the offender, but amenability to and success of treatment are not required.18 Incapacitation to prevent public harm is a valid purpose of SVP laws,18 as it is for both public health policy and criminal punishment. The fact that SVP laws provide higher due process rights, similar to criminal procedures, such as proof beyond a reasonable doubt, does not render such acts as criminal in nature.

At the outset SVP determination with its consequent disposition must have considered this to be the least restrictive treatment.19 Although treatment need not be effective, an effort at treatment must be made.18 It is unknown whether offenders in SVP programmes can be constitutionally compelled to disclose their prior sexually offending acts, at risk of further prosecution, as can occur in prison voluntary sexual offender treatment programmes.20 SVP programmes differ in that they are involuntary.

Opposition to SVP laws

In the late 1980s, the Criminal Justice Standards Committee of the American Bar Association recommended the repeal of sexual psychopath laws.6 Most states had already either repealed or substantially modified their commitment statutes for SDPs. The committee observed a growing professional literature from mental health and mental retardation professionals that criticised sexual psychopath laws, defined as those “which provide for the special sentencing and treatment of sexual psychopaths, psychopaths, or defective delinquents…”. Commentary faulted these psychopath laws for insufficient scientifically valid support and failure to meet the legislative purposes of the laws.1,21 The committee also acknowledged reports of psychopath laws reducing recidivism rates.22,23 The committee did not simply criticise psychopath laws and recommend their repeal, it offered a solution to the need for public safety that started SDP legislation. Repeat offenders, particularly those who manifest patterns of criminality that endanger society, can be dealt with under habitual offender laws or other statutes providing for sentence enhancement. Those offenders with mental illness or mental retardation can be sentenced and treated in a manner that addresses their treatment and rehabilitation needs.

In 1955, the Maryland Defective Delinquency Law resulted in the opening of the Patuxent Institutions to admit offenders with a variety of criminal offences including but not limited to sexual offences. This was a step-down programme in the context of indefinite commitment. Over 8 years, 81 persons were paroled, 41 (51%) of them violated their parole but only 28 by commission of a new offence. The programme was considered successful in that 65% did not commit a crime while on parole.23

Pacht et al.22 referred to sexual offenders with “sexual immaturity and a compulsive need to act out [their] immature sexual cravings” as ‘sexually deviated’. The theoretical underpinning of the programme was psychodynamic, which in practice introduced individual and group therapy as well as education. Over the 9-year period through May 1966, 1605 were committed to the Wisconsin Department of Public Welfare for diagnosis. Of these, 751 (47%) were non-deviated, 783 (49%) were deviated, and 66 (4%) were psychotic, mentally deficient or epileptic who were managed according to the Mental Health Act. Of the 783 deviated individuals, 146 were placed on probation with outpatient treatment and 632 were recommitted to prison for treatment. Of those who were recommitted to prison and in need of specialised treatment, 475 were granted parole; only 81 (17%) of these violated parole, with 43 (9%) committing a sexual offence. The parole violation rate of 17% was much lower than that for those paroled from the general prison population.

A common tension in mental health and criminal law is that which exists between the liberty and due process rights of the offender and the government’s obligation to protect the public from criminal victimisation. Scholarly discourse from both mental health and legal fields has tended to advocate for the liberty interests or leniency with regard to the individual offender, whereas courts, in particular the Supreme Court, are more likely to address and give weight to public protection. This polarisation, with legislatures and courts more reflective of public opinion, has been pronounced in shaping public policies dealing with sexual offenders at risk for recidivism.

Although academics seem to favour leniency or depathologisation, there is no aggregate coherent ideological framework. For example, Isaac Ray24 in the 19th century and Gregory Zilboorg25 in the 20th century advocated exempting or reducing criminal responsibility of severe personality disordered individuals using the term moral insanity (currently severe psychopathy).26 This can be seen as lenient in that it would spare the individual from criminal punishment (including death sentence). Acknowledging the need to protect the public from violent crimes and predations by such individuals having been spared culpability and punishment, the public protection solution of each of these thoughtful commentators was civil commitment.

In 1999, the American Psychological Association criticised SVP statutes on grounds that “treatment efficacy is controversial for every approach”, that civil commitment should be permitted only for individuals with a ‘severe mental disorder’, and that “to date there is no clear basis for making the claim that treatment of any class of patients with paraphilias will result in lower rates of recidivism.” It was concluded that “psychiatrists must vigorously oppose these statutes in order to preserve the moral authority of the profession and to ensure continuing societal confidence in the medical model of civil commitment.”

Rather than SVP legislation, the American Psychological Association recommended a two-prong approach for SDPs. First, adequate funding should be provided for voluntary treatment programmes within correctional settings. Second, societal concerns about the need for punishment and incapacitation of SDPs should be met through customary sentencing alternatives within the criminal justice system and not through involuntary civil commitment statutes.

Conclusions

SVP laws in the United States are intended to treat and rehabilitate the offenders’ predisposing mental abnormality or personality disorder and to protect the public by incapacitation. The goals of SVP legislation are essentially the same as those of the preceding sexual psychopath statutes. The Supreme Court has addressed constitutional aspects of SVP laws to ensure substantial uniformity of these laws across jurisdictions. Nevertheless, differences in procedures, substance, and practice exists. SVP laws are constitutional, popular, and effective. Yet constitutional challenges are likely to continue, especially over how SVP laws are implemented.

Acknowledgement

The authors have no financial support or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry; Committee on Psychiatry and Law. Psychiatry and sexual psychopath legislation, the 30s to the 80s. New York: Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry; 1977.

- Hood Crime, criminology and public policy. New York: Free Press; 1974.

- Brownmiller Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1975.

- Sutherland EH. The diffusion of sexual psychopath laws. Am J Sociol 1950;56:142-8. Crossref

- Cleckley H. The mask of sanity: an attempt to clarify some issues about the so-called psychopathic 2nd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1950.

- Erickson WH, Early NS Jr, Zenoff EH. Special dispositional statues, Part VIII. In: ABA Criminal Justice Mental Health Standards. Washington, DC: American Bar Association; 1989:453-61.

- American Bar Association Criminal Justice Mental Health Washington, DC; 1989.

- Sutherland EH. The sexual psychopath laws. J Crim Law Criminol 1950;40:543-51. Crossref

- Weiner Legal issues raised in treating sex offenders. Behav Sci Law 1985;3:325-40. Crossref

- Tucker DE, Brakel SJ. Sexually violent predator laws. In: Principles and Practice of Forensic Psychiatry. Rosner R, Scott C, editors. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group; 2017.

- DeMatteo D, Murphy M, Galloway M, Krauss DA. A national survey of United States sexually violent person legislation: policy, procedures, and practice. Int J Forensic Ment Health 2015;14:245-66. Crossref

- Burick Analysis of the Illinois Sexually Dangerous Persons Act. J Crim Law Criminol 1968;59:254-66. Crossref

- Brennan RA. Keeping the dangerous behind bars: redefining what a sexually violent person is in Illinois. Valparaiso Univ Law Rev 2011;45:551-94.

- In re Commitment of Bohannan, in W. 3d. Tex. 296 (2012)

- Specht Patterson, in U.S. 605 (1967).

- Dred Scott Sandford, in U.S. 393 (1857)

- Allen v. Illinois, in U.S. 85-5404. 478 364 (1986).

- Kansas Hendricks, in U.S. Ct 2072. 346 (1997).

- In re Young and Cunningham, in 857 (1993).

- McCune Lile, in F. 3d 1175 (2000).

- Monahan J, Davis S. Mentally disordered sex offenders. In: Mentally Disordered Offenders. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. Crossref

- Pacht AR, Halleck SL, Ehrmann JC. Diagnosis and treatment of the sexual offender: a nine-year Am J Psychiatry 1962;118:802-8. Crossref

- Boslow HM, Kohlmeyer The Maryland Defective Delinquency Law: an eight-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1963;120:118-24. Crossref

- Ray I. A treatise on the medical jurisprudence of insanity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1962. Crossref

- Hall JK, Zilboorg G, Bunker HA; American Psychiatric Association. One hundred years of American psychiatry. New York: Columbia University Press;

- Felthous AR. Psychopathic disorders and criminal responsibility in the Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010;260(Suppl 2):S137-41. Crossref