East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2020;30:73-8 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1938

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Farshid Shamsaei, Professor, Behavioral Disorders and Substance Abuse Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Martin Grosse Holtforth, Professor, Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland & Head Researcher, Psychosomatic Competence Center, Inselspital, Bern, Switzerland

Address for correspondence: Martin Grosse Holtforth, Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Fabrikstr. 8, CH-3012, Bern, Switzerland.

Email: martin.grosse@psy.unibe.ch

Submitted: 20 May 2019 Accepted: 4 February 2020

Abstract

Objective: This study aims to develop and validate the stigma assessment tool for family member caregivers of patients with mental illness (SAT-FAM).

Methods: This study was conducted in three phases: (1) explicate the concept of stigma towards family caregivers of patients with mental illness, (2) develop and iteratively optimise a preliminary version of the SAT-FAM, and (3) test the psychometric properties of the final version of the SAT-FAM. In phase 1, 14 family caregivers of patients with mental illness were interviewed for qualitative data collection and analysis. Four themes emerged: people’s reaction and attitude, compassion with fear, rejection and loneliness, and confusion about mental illness. In phase 2, the first draft of the SAT-FAM with 38 items was developed. Based on the content validity index, each item was evaluated by 15 experts using a 4-point scale (1 = not relevant; 4 = very relevant). 15 family member caregivers of patients with mental illness were randomly selected to complete the face validity form on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). In phase 3, 286 family caregivers of people with mental illness were recruited for exploratory factor analysis. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s coefficient) and test-retest reliability were measured.

Results: The final draft of the SAT-FAM comprised 30 items in four factors: shame and discrimination, social interaction, emotional reaction, and avoidance behaviours. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was >0.89 for all factors. The test-retest reliability among 30 family caregivers was good (0.76). Conclusions: The SAT-FAM is a valid and reliable self-report instrument for assessing stigma towards family caregivers of patients with mental illness. It enables a practical way of evaluating interventions aimed at reducing stigma.

Key words: Caregivers; Mental disorders; Psychometrics; Social stigma

Introduction

Mental illness is commonly associated with chronic diseases and their concomitant morbidity and mortality.1 The World Health Organization estimates that mental disorders will constitute the largest global burden of diseases by 2020, and that one in four families worldwide has at least one member having a mental disorder.2 Chronic mental illness is a critical life event and major stressor for immediate family members.2 Patients with mental illness and their family members face many problems, barriers, and disadvantages.3 People with mental illness are more likely to be unemployed, have lower income, experience more psychological distress in addition to the psychopathology, receive less social support, and have a diminished quality of life.4

Many mental illnesses first occur in adolescents who still live with their immediate family members.5 Even when they have grown older and moved out from the parent’s home, their condition is still likely to affect the lives of family members.6 People with mental illness and their family members are frequently stigmatised by the general public.4 Although experiences of stigmatisation are pervasive among people with mental illness, the impact of these experiences varies widely among individuals.7 Cultural differences may influence the experience of stigma in families of psychiatric patients.8 One source of stigma cannot replace another; it is important to pay more attention to gender, race, and immigrant identities in the stigmatised family.9 In traditional Iran society, families are expected to care for their members. Therefore, illness is a family issue rather than an individual problem.

Stigma refers to a discrediting or disgraceful mark that sets individuals apart from others and renders them tainted, degraded, or inferior in the eyes of other people.4

Stigmatisation is a complex social process. Stigma is associated with oversimplified conceptions, opinions, or images about a person or group (stereotypes), negative attitudes as a part of such stereotypes (prejudice), and overt negative behaviours (discrimination) towards people with a stigmatised condition.10,11

Manifestations of stigma may be overt and include repulsion, disgust, avoidance, rejection, dehumanisation, degradation, discredit, and depersonalisation of others. Stigmatisation may also manifest subtly. People may display their underlying emotions and feelings through nonverbal expressions of distress, anxiety, or unease.12 Stigmatisation can lead to social exclusion, poor treatment, or other negative social interactions.13 Stigma deprives people from their dignity, challenges their humanity, and interferes with their full participation in society.13 The pervasiveness of stigma is similar across countries and times.14

Family caregivers of individuals with mental illness are stigmatised in many societies, and stigmatisation was reported to be more intense in Asia.6 The stigma towards mental illness entails negative consequences for both patients and caregivers that add to self-stigmatisation and low self-esteem.15 Family caregivers are often discriminated and isolated, avoid social interactions, and face social exclusion.16 As a consequence of the perceived stigma, the caregivers may conceal their relationship with the patient, fail to acknowledge the illness, and prevent adequate treatment of the patient. Also, general attitudes towards mental illness may shape the way family caregivers are treated in a society. Such negative attitudes may hinder social integration of the family members. In contrast, positive attitudes held by the caregivers themselves may facilitate supporting the patient regarding prevention, early treatment, and rehabilitation.17,18 Thus, it is essential for health professionals to better understand this phenomenon, especially with regard to how it affects a family unit.19

There is no validated tool for assessment of stigma towards caregivers of individuals with mental disorder. This study aims to develop and validate the stigma assessment tool for family member caregivers of patients with mental illness (SAT-FAM).

Methods

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (reference: IR.UMSHA.REC.1395.297). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. This study was conducted in three phases: (1) explicate the concept of stigma of family caregivers of patients with mental illness, (2) develop and iteratively optimise a preliminary version of the SAT-FAM, and (3) test the psychometric properties of the final version of the SAT-FAM.

Phase 1

A hermeneutic/phenomenological approach was used to explicate the concept of stigma towards family caregivers of patients with mental illness and identify potential subcategories. Hermeneutic phenomenology is a method used to describe, interpret, and understand lived experience in an effort to discover meaning rather than to explain and predict. The phenomenological research method is a systematic, explicit, self-critical, and intersubjective study of its subject matter, of lived experience. Phenomenology is a way to investigate subjective phenomena, and it is based on the belief that essential truths about reality are grounded in everyday experience. Because phenomenology examines the meaning that lived experience has in people’s lives, it is a valuable research method in nursing.20

14 family caregivers who had provided care for >1 year to patients diagnosed with mental illness based on the DSM-5 were purposively selected from October 2016 to June 2017 at Farshchian Psychiatry Hospital of Hamedan city in Iran. The sample included eight mothers, one sibling, three spouses (one husband and two wives), two sons, and two daughters. 64% were female. 83% were married, 3% were divorced, 9% were single, and 5% were widowed. Most participants were employed and educated beyond high school. Caregiving experience ranged from <2 years to >17 years.

Face-to-face interviews were conducted; each interview session lasted 45 to 60 minutes. Interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed following the Van Manen process of data analysis that involves reflecting on essential themes that characterise the phenomenon.20 Data were analysed through a circuitous process in which reflection was initiated with the first interview, continued concurrently with data collection, and included listening to audiotapes and reading of transcripts multiple times. Each transcript was read in its entirety to obtain a sense of the whole, and then broken down line by-line to identify significant statements and key words. Data were then organised in a four-column table. Original verbatim data were recorded in column 1, significant statements in column 2, formulated meaning statements in column 3, and key elements to identify themes in column 4 (through recognition of similarities and differences).

Four themes emerged from the analysis: people’s reaction and attitude, compassion with fear, rejection and loneliness, and confusion about mental illness.

Phase 2

The four themes derived were used in the development of the first draft of the SAT-FAM, with 38 items. Based on the content validity index, each item was evaluated by 15 psychologists, psychiatrists, and nursing experts using a 4-point scale (1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = quite relevant, and 4 = very relevant). In addition, experts were asked: (1) what revisions should be made, and (2) what suggestions should be included. Some wording revisions were made according to the experts’ suggestions.

Face validity evaluates the appearance of the questionnaire in terms of feasibility, readability, consistency of style and formatting, and the clarity of the language. An evaluation form was developed to assess each question in terms of clarity of wording, the likelihood that the target audience would be able to answer the questions, as well as layout and style. 15 family member caregivers of patients with mental illness were randomly selected to complete the face validity form on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 (strongly disagree = 1, disagree = 2, agree = 3, and strongly agree = 4).

Phase 3

Exploratory factor analysis for construct validity was computed to validate the constructs of the SAT-FAM. Factors were extracted based on the results of (1) Bartlett’s test of sphericity for testing the hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix; (2) Kaiser-Meyer- Olkin test for measuring sampling adequacy; (3) a scree plot for determining the number of factors by identifying distinct breaks in the slope of the plot; (4) the eigenvalue (λ) of >1.0 for representing the amount of variance in all of the items that can be explained by a given factor; (5) a cutoff of ≥0.40 for factor loading for retaining items; and (6) the conceptual consideration for placing items with the factor.21

The sample for factor analysis was 286 family caregivers (participants in phase 1 were excluded) recruited from our unit. Exploratory factor analysis examines the relationships among variables without determining a particular hypothetical model.22 Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and test-retest reliability of the SAT-FAM was measured.

Results

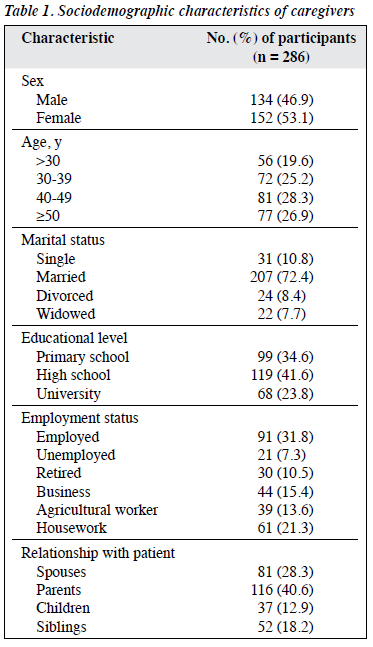

A total of 286 family caregivers aged 19 to 67 (mean, 46.3) years were included (Table 1). 53% were women. 82% were living in the same household with the patient. 72.4% were married. 41.6% had a high school degree. 31.8% were employed.

A rating of 3 (quite relevant) or 4 (very relevant) indicates that the content of an item in the first draft is valid and consistent with the conceptual framework. For example, if five of eight experts rate an item as relevant (3 or 4), the content validity index would be 0.69, which does not meet the 0.79 level required and should be dropped.21 Two items on the draft SAT-FAM were deemed to be invalid because they yielded a content validity index of 0.62 (5/8) and 0.75 (6/8). The remaining items were valid with content validity index ranging from 0.87 (7/8) to 0.100 (8/8).

All 15 family member caregivers of patients with mental illness rated each item at three or four on a Likert scale of 1 to 4. 95% indicated that they understood the questions and found them easy to answer, and 90% indicated that the appearance and layout were acceptable to the intended target audience. In quantitative analysis, three items had an item impact score of <1.5 and were eliminated from the final version. After content validity and face validity, five items were deleted or merged, so that 33 items were retained.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test statistic varies between 0 and 1. A value of 0 indicates that the sum of partial correlations is large in comparison to the sum of correlations, which indicates diffusion in the pattern of correlation, and that factor analysis is inappropriate.21

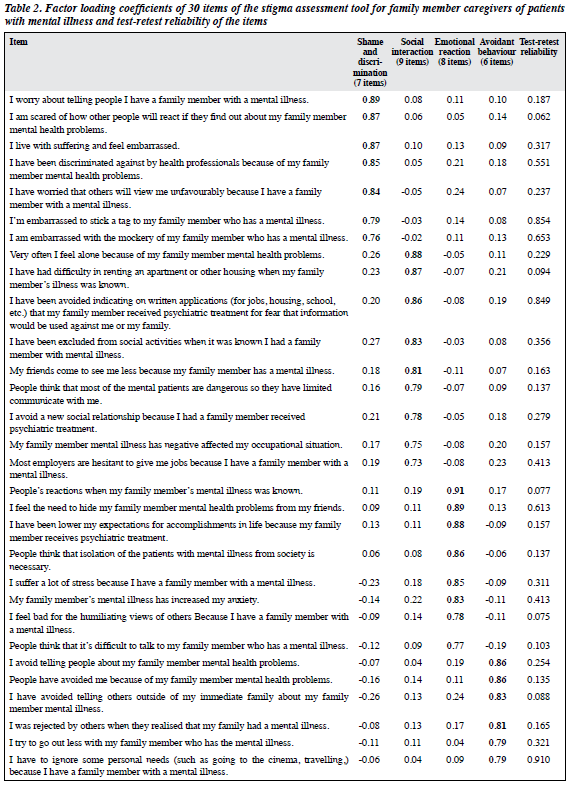

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test sampling adequacy on the SAT-FAM was 0.93, and the determinant was small and close to 0 (0.001) indicating the data were legitimately factored.22 Bartlett test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 14476.55, p = 0.0001), indicating that the correlation matrix was not an identity matrix. Five factors’ Eigenvalues were >1, and a discontinuity between the third and fourth factor was identified in the screen test. The 4-factor model accounted for 51.3% of the total variance. The Steven guideline is based on sample size and suggests that the statistically acceptable loading for 50 participants is 0.72, for 100 participants 0.51, and for 200 to 300 participants 0.29-0.38.23 The sample size in the SAT-FAM validation process was 286, so that three items with a loading of <0.4 were deleted. The remaining 30 items with a loading of ≥0.4 were retained (Table 2).

The first factor was ‘shame and discrimination’ and comprised seven items related to feeling guilty, to negative judgements, and to perceived devaluation/discrimination. The second factor was ‘social interaction’ and comprised nine items related to losing employment, housing, having a poor reputation and family burden, and to leisure activities. The third factor was ‘emotional reaction’ and comprised eight items related to aggressive emotions (eg, anger, irritation), prosaic reactions (desire to help, sympathy) and feelings of anxiety (uneasiness, fear). The fourth factor was ‘avoidant behaviours’ and comprised six items related to social isolation, avoidance of social relationship, and anticipation of rejection.

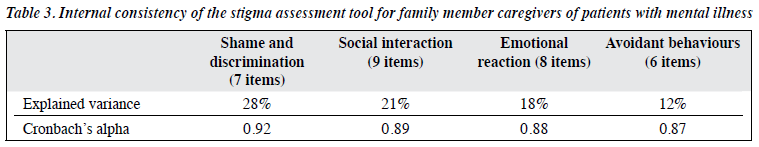

The SAT-FAM resulted in high or very high Cronbach’s alpha for all themes (0.87-0.92, Table 3). The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was satisfactory (>0.89) for all factors.

Test-retest reliability of the SAT-FAM was assessed in 30 family caregivers who completed the SAT-FAM at baseline and 4 weeks later. Because the scale was not continuous, Wilcoxon non-parametric test was deemed to be more appropriate than Pearson correlation coefficient.23

The test-retest reliability of the SAT-FAM was good (0.76), with value for each item shown in Table 2.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to develop and validate perceived and/or experienced stigma scales for caregiving family members of a patient with mental illness. Stigma about mental illness may determine how and even whether people seek help for mental health problems, their level of engagement with treatment and the outcome of their problems.4 The SAT-FAM may contribute to our understanding of processes that affect help-seeking, treatment uptake, and outcome of mental illness treatment. The experiences of family caregivers impact all aspects of their life, including physical, emotional, and psychological health.6 Little is known about the context and potential consequences of administering a caregiver questionnaire in the clinical setting for caregivers or patients themselves.16,24

Assessment is a critical step in determining appropriate support services. Caregiver assessment is a systematic process of gathering information to describe a caregiving situation. It identifies the particular problems, needs, resources, and strengths of the family caregivers and approaches issues from the caregiver perspective and culture to help caregivers maintain their health and well- being.

The content validity of the SAT-FAM was supported by the expert panel. The content validity index was high because the SAT-FAM was based on family member caregivers’ lived experiences and in-depth interviews. The favourable psychometric properties support the use of the SAT-FAM.

The SAT-FAM may help with stigma reduction strategies. In a qualitative study of strategies in reducing the stigma towards people with mental disorders in Iran, major themes emerged were ‘emphasis on education and changing attitudes’, ‘changing the culture’, ‘promoting supportive services’, ‘role of various organisations and institutions’, ‘integrated reform of structures and policies to improve the performance of custodians’, and ‘evidence-based actions’.8

The content of the SAT-FAM arose directly from an earlier qualitative research. Although we do not suggest that this approach is superior to, or distinct from, the one based on theoretical conceptions of perceived stigma, the items derived resonated with current theory about stigma. The SAT-FAM directly reflects the lived experience of stigma and may help to extend our current theoretical concepts. We did not examine how stigma varied with demographic and clinical characteristics of participants, as they were not representative. Thus, further evaluation in larger and heterogeneous groups of family caregivers of patients with mental illness is needed. The present study was exploratory and did not sufficiently validate the stigma tool, but its findings have implications for research and practice.

Conclusion

The SAT-FAM is a valid and reliable self-report instrument for assessing stigma towards family caregivers of patients with mental illness. It enables a practical way of evaluating interventions aimed at reducing stigma.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the family members, staff, and officials who played a role in this study.

Funding

This project was supported by the Behavioral Disorders and Substance Abuse Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Iran (grant number: 940924184). Financial support was provided by the vice chancellor of the research and technology sector of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

Declaration

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Shamsaei F, Nazari F, Sadeghian E. The effect of training interventions of stigma associated with mental illness on family caregivers: a quasi- experimental study. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2018;17:48. Crossref

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. Available at: www.who.int/aboutllicensing/copyright form/en/index. html. Accessed 20 May 2019.

- Santos AFO, Cardoso CL. Family members of individuals suffering from mental disorders: stress and care stressors. Estudos de Psicologia 2015;32:87-95. Crossref

- Bos AER, Pryor JB, Reeder G, Stutterheim S. Stigma: advances in theory and research. Basic Appl Soc Psych 2013;35:1-9. Crossref

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593-602. Crossref

- Shamsaei F, Mohamad Khan Kermanshahi S, Vanaki Z, Holtforth MG. Family care giving in bipolar disorder: experiences of stigma. Iran J Psychiatry 2013;8:188-94.

- Corrigan PW. Shapiro JR. Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:907-22. Crossref

- Taghva A, Farsi Z, Javanmard Y, Atashi A, Hajebi A, Noorbala AA. Strategies to reduce the stigma toward people with mental disorders in Iran: stakeholders’ perspectives. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:17. Crossref

- Snowden LR, Yamada AM. Culture differences in access to care. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1:143-66. Crossref

- Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, Thornicroft G. Experiences of mental illness stigma, prejudice and discrimination: a review of measures. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:80. Crossref

- Phelan JC, Link BG, Dovidio JF. Stigma and prejudice: one animal or two? Soc Sci Med 2008;67:358-67. Crossref

- Drapalski AL, Lucksted A, Perrin PB, Aakre JM, Brown CH, DeForge BR, et al. A model of internalized stigma and its effects on people with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2013;64:264-9. Crossref

- Karnieli-Miller O, Perlick DA, Nelson A, Mattias K, Corrigan P, Roe D. Family members’ of persons living with a serious mental illness: experiences and efforts to cope with stigma. J Ment Health 2013;22:254-62. Crossref

- Fabrega H. The culture and history of psychiatric stigma in early modern and modern Western societies: a review of recent literature. Compr Psychiatry 1991;32:97-119. Crossref

- Suto M, Livingston JD, Hole R, Lapsley S, Hinshaw SP, Hale S, et al. “Stigma shrinks my bubble”: a qualitative study of understandings and experiences of stigma and bipolar disorder. Stigma Res Action 2012;2:85-92.

- Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol 2004;59:614-25. Crossref

- Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Link BG, Struening E, Kaczynski R, Gonzalez J, et al. Perceived stigma and depression among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:535-6. Crossref

- Shamsaei F, Kermanshahi SM, Vanaki Z, Hajizadeh E, Holtforth MG, Cheragi F. Health status assessment tool for the family member caregiver of patients with bipolar disorder: development and psychometric testing. Asian J Psychiatr 2013;6:222-7. Crossref

- Park S, Park KS. Family stigma: a concept analysis. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2014;8:165-71. Crossref

- Van Manen M. Researching Lived Experience. Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy, 3nd ed. Ontario: Althouse press; 2001.

- DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, Ernst DM, Hayden SJ, Lazzara DJ, et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;39:155-64. Crossref

- Bryman A, Cramer D. Quantitative Data Analysis with SPSS12 and 13. A Guide for Social Scientists. London: Routledge; 2005. Crossref

- Stevens JP. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 5th ed. New York: Taylor & Francis Group; 2009.

- Deeken JF, Taylor KL, Mangan P, Yabroff KR, Ingham JM. Care for the caregivers: a review of self-report instruments developed to measure the burden, needs, and quality of life of informal caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;26:922-53. Crossref