East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2024;34:9-13 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2346

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Velayudhan Rajmohan, NM Aparna

Abstract

Background: COVID-19 infection is associated with significant depressive and anxiety symptoms and stress. We examined the prevalences of depressive and anxiety symptoms and perceived stress among patients with COVID-19.

Methods: Clinically stable patients with COVID-19 aged 18 to 60 years who were admitted between April 2021 and September 2021 to the MES Medical College in Kerala, India were prospectively recruited. They were assessed using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Anxiety Scale, and the Perceived Stress Scale.

Results: Of 112 patients screened, 103 were included in the analysis. Depression scores were higher in patients of lower socio-economic status (p = 0.04), of unemployed (p = 0.01), and with longer hospital stays (p < 0.001). Anxiety scores were higher in patients aged 31 to 40 years (p = 0.04), of lower socio- economic status (p = 0.01), with a history of psychiatric illness (p = 0.006), and with a history of self- harm (p = 0.019). Perceived stress scores were higher in patients of lower socio-economic status (p = 0.02), with a history of psychiatric illness (p = 0.001), and with a history of self-harm (p = 0.022).

Conclusion: Socio-economic status, employment status, a history of psychiatric illness, and duration of hospital stay are associated with depression, anxiety, and stress among patients with COVID-19.

Key words: Anxiety; COVID-19; Depression; Stress, psychological

Velayudhan Rajmohan, Department of Psychiatry, KMCT College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India

NM Aparna, Department of Psychiatry, MES Medical College, Malappuram, Kerala, India

Submitted: 4 October 2023; Accepted: 15 February 2024

Patients with COVID-19 are at high risk of developing psychiatric and psychological illnesses.1 Viral respiratory diseases are associated with both acute and chronic psychological sequelae among survivors. Coronavirus exposure (following outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome) can cause post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.2 Patients with COVID-19 may experience delirium, depression, anxiety, and insomnia; these can be mediated directly through viral infection of the central nervous system or indirectly through immune response.3 Patients with COVID-19 have higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, with the prevalence for these conditions being 54.3%, 97.3%, and 46.6%, respectively.

In 100 hospitalised patients with COVID-19 in India, the prevalences of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance are 27%, 67%, and 62%, respectively.4 Depression and anxiety are associated with medical comorbidities (eg, diabetes, hypertension) and the severity of COVID-19. In a cohort of urban patients with COVID-19 in Kerala, India, 9.7% have clinically significant depression (7.8% mild, 1.3% moderate, and 0.6% severe) and 5.8% have clinically significant anxiety (5.2% mild and 0.6% severe).5 Studies of behavioural symptoms in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 are limited. Thus, the present study aimed to examine the prevalences of depressive and anxiety symptoms and perceived stress among patients with COVID-19 at a rural tertiary hospital in India.

This cross-sectional study included clinically stable (category-B: high-grade fever and/or severe sore throat/ cough6) patients with COVID-19 aged 18 to 60 years who were admitted between April 2021 and September 2021 to the MES Medical College in Kerala, India. The sample size was set at 100, based on a previous study.4 Consecutive sampling was used; patients who met the inclusion criteria were included until the estimated sample size was reached. Patients who were unable to complete the questionnaires or had suspected cognitive disorders were excluded.

The diagnosis of COVID-19 was based on results of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and examinations by resident pulmonologists. Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale.7 Total scores range from 0 to 54; higher scores indicate higher severity (0-6 no depression, 7-19 mild, 20-34 moderate, and ≥35 severe). Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Hamilton Anxiety Scale.8 Total scores range from 0 to 56; higher scores indicate higher severity (≤7 no/minimal anxiety, 8-14 mild, 15-23 moderate, and ≥24 severe). Stress levels were assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale.9 Total scores range from 0 to 40; higher scores indicate higher severity (0-13 low, 14-26 moderate, and 27-40 high). All scales were administered by two psychiatry residents within 48 hours of admission unless patients presented with fatigue and delirium at the time of admission.

Data were compared using the t-test, Pearson correlation, or analysis of variance with post-hoc Bonferroni correction, as appropriate. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Windows version 16.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Of 112 patients recruited, four did not consent and five did not complete the assessments; the remaining 103 were included in the analysis (Table 1). Of these, most were hospitalised for 1 to 10 days (79.2%), had an identified primary COVID-19 contact before the onset of infection (59.2%), and had family members with COVID-19 (50.5%). Regarding their medical and psychiatric histories, 46.6% of patients had at least one medical comorbidity, 3.3% had a history of psychiatric illness, 1.9% had a history of self- harm, and 4.9% had substance use.

Of the patients, 2.9% had no depression, 88.3% had mild depression, and 8.7% had moderate depression, whereas 80.6% had mild anxiety and 19.4% had moderate anxiety, and 44.7% had mild stress and 55.3% had moderate stress. Depression scores were positively correlated with anxiety scores (r = 0.73, p < 0.001) and perceived stress scores (r = 0.60, p < 0.001), and anxiety scores were positively correlated with perceived stress scores (r = 0.71, p < 0.001).

Depression scores were higher in patients of lower socio-economic status compared with middle socio- economic status (14.47 vs 12.56, t = 2.04, p = 0.04), in patients who were unemployed compared with employed (14.98 vs 12.80, t = –2.52, p = 0.01), and in patients hospitalised for 11 to 20 days compared with those hospitalised for 1 to 10 days (16.90 vs 13.10, t = –3.67, p < 0.001) [Table 2]. Depression scores were not associated with sex, age, religion, marital status, medical comorbidity, history of psychiatric illness, substance use, or history of self-harm.

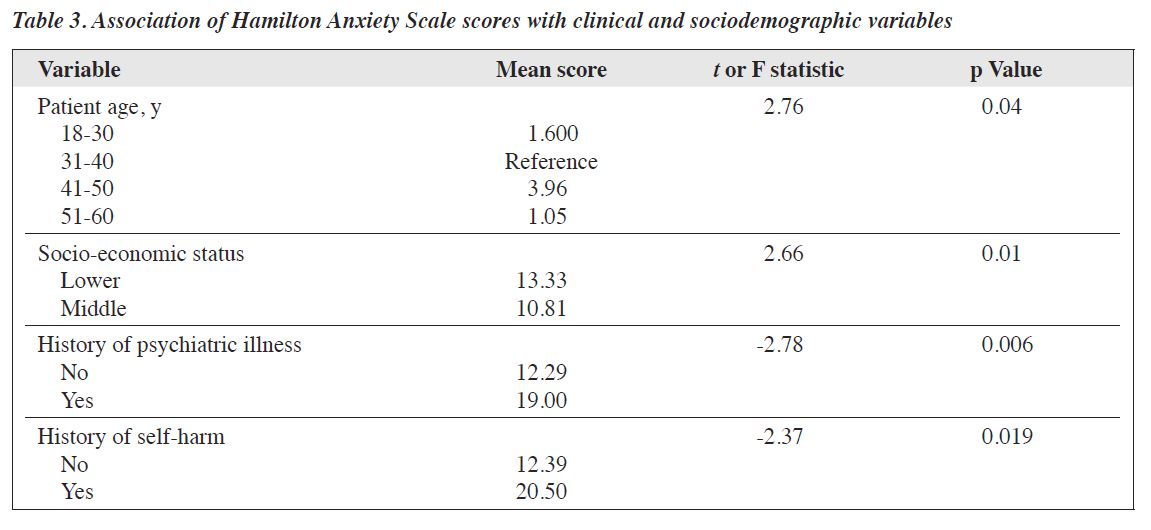

Anxiety scores were lowest among patients aged 51 to 60 years and highest among patients aged 31 to 40 years, followed by patients aged 41 to 50 years (F = 2.76, p = 0.04). Anxiety scores were higher in patients of lower socio- economic status compared with middle socio-economic status (13.33 vs 10.81, t = 2.66, p = 0.01), in patients with a history of psychiatric illness compared with those without (19.00 vs 12.29, t = –2.78, p = 0.006), and in patients with a history of self-harm compared with those without (20.50 vs 12.39, t = –2.37, p = 0.019) [Table 3]. Anxiety scores were not associated with sex, religion, marital status, medical comorbidity, substance use, or employment status.

Perceived stress scores were higher in patients of lower socio-economic status compared with middle socio- economic status (15.63 vs 12.81, t = 3.29, p = 0.02), in patients with a history of psychiatric illness compared with those without (22.00 vs 14.46, t = –3.43, p = 0.001), and in patients with a history of self-harm compared with those without (22.00 vs 14.61, t = –2.33, p = 0.022) [Table 4]. Perceived stress scores were not associated with sex, age, religion, marital status, medical comorbidity, substance use, or employment status.

COVID-19 infection is associated with significant depressive and anxiety symptoms and stress. In the present study, 97% of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 had mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms; the prevalence is higher than the 27%4 and the 9.1%5 reported in previous studies in India. Depression scores were significantly higher in patients of lower socio-economic status, unemployed, and with longer hospital stays. The latter may be due to the illness itself, as depression is associated with severity of illness.4 However, there was no association between depression and medical comorbidities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, negative emotions were intensified by lack of community services, collapse of industries, unemployment, and financial crisis.10

In the present study, all patients reported to have mild-to-moderate anxiety and stress; the prevalence of anxiety is higher than the 67%4 and the 5.2%5 reported in previous studies in India. Levels of anxiety and stress were significantly higher in patients of lower socio-economic status or with a history of psychiatric illness or self-harm. This is in keeping with the finding of an earlier study with a similar cohort.10 COVID-19 can result in anxiety and excessive stress or anger.11 Anxiety scores were lowest among older patients and highest among middle-aged patients. This echoes an earlier study that found that older individuals were less afraid of COVID-19, despite their increased risk, and were less upset by the lockdown.12

Depression, anxiety, and stress scores in patients with COVID-19 can be confounded by illness-related factors such as fatigue and viral load, which are associated with a greater risk of developing these symptoms; this supports a psycho-neuroendocrine-immune interplay.13 Antivirals may affect the onset and course of depression and anxiety; for example, favipiravir has been shown to exert a protective effect against depressive mood and loss of interest.14

Patients with psychiatric conditions are prone to recurrence or deterioration of symptoms and may frequently self-monitor and therefore experience high levels of health- related stress and anxiety. Stress levels influence behaviour and decision-making among patients with COVID-19.15

This may result in repeated testing, repeated emergency room visits, and self-medication; these behaviours place a burden on healthcare resources.15 Thus, patients with psychiatric illness should be identified and treated early to minimise such behaviours.

Limitations of the present study include the small sample size, the tertiary setting, the lack of diagnostic assessments, the cross-sectional design, and the lack of follow-up. Additionally, treatment factors and their effects and the impacts of severe illness were not assessed. Therefore, larger and more comprehensive multiple-arm studies are warranted.

Socio-economic status, employment status, history of psychiatric illness, and duration of hospital stays are associated with depression, anxiety, and stress among patients with COVID-19. Early psychiatric treatment may help prevent unnecessary and excessive healthcare utilisation in terms of repeated testing, repeated emergency room visits, and self-medication.

Both authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Both authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee MES Academy of Medical Sciences - Perinthalmanna (reference: IEC/MES/04/2021). The patients were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

- Moayed MS, Vahedian-Azimi A, Mirmomeni G, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress among patients with COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Adv Exp Med Biol 2021;1321:229-36. Crossref

- Mazza MG, De Lorenzo R, Conte C, et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun 2020;89:594-600. Crossref

- Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:611-27. Crossref

- Yadav R, Yadav P, Kumar SS, Kumar R. Assessment of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance in COVID-19 patients at tertiary care center of north India. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2021;12:316-22. Crossref

- Uvais NA, Moideen S, Babu F, Rajagopal S, Maheshwari V, Gafoor TA. Depression and anxiety among patients with active COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2021;23:20br02996. Crossref

- Health and Family Welfare Department. Government of Kerala. Revised guidelines for testing, quarantine, hospital admission, and discharge of COVID-19 based on current risk assessment. Accessed 4 May 2022. Available from: https://dhs.kerala.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/reg_12032020.pdf.

- Fantino B, Moore N. The self-reported Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale is a useful evaluative tool in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2009;9:26. Crossref

- Maier W, Buller R, Philipp M, Heuser I. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord 1988;14:61-8. Crossref

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385-96. Crossref

- Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020;14:779-88. Crossref

- Dubey S, Dubey MJ, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S. Children of frontline coronavirus disease-2019 warriors: our observations. J Pediatr 2020;224:188-9. Crossref

- Nair DR, Rajmohan V, Raghuram TM. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle and psychosocial stress: an online survey. Kerala J Psychiatry 2020;33:5-15. Crossref

- Ausserhofer D, Mahlknecht A, Engl A, et al. Relationship between depression, anxiety, stress, and SARS-CoV-2 infection: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol 2023;14:1116566. Crossref

- Herman B, Bruni A, Zain E, Dzulhadj A, Oo AC; Viwattanakulvanid. Post-COVID depression and its multiple factors, does Favipiravir have a protective effect? A longitudinal study of Indonesia COVID-19 patients. PLoS One 2022;17:e0279184. Crossref

- Asmundson GJG, Taylor S. How health anxiety influences responses to viral outbreaks like COVID-19: what all decision-makers, health authorities, and health care professionals need to know. J Anxiety Disord 2020;71:102211. Crossref