East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2025;35:28-31 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2464

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Ragy R Girgis, Hannah Hesson, Paul S Appelbaum, Gary Brucato

Abstract

Objectives: Mass murder is associated with a lifetime history of substance use. We aimed to examine cannabis involvement among those who committed mass shootings in the United States from 1900 to 2019.

Methods: We identified mass shooting events in the United States from 1900 to 2019 using publicly available English-language media reports and court/police records. People who perpetrated mass murders using methods other than firearms (eg, knives, automobiles) were used as a comparison group. Events were dichotomised into either prior to 1996 or from 1996 onward (first legalisation for medical use by California). Post-1960 data were used for additional analyses of a more modern era.

Results: The proportion of those who committed mass shootings who had used, possessed, and/or distributed cannabis was significantly higher for events that occurred from 1996 onward, compared with prior to 1996 (11.2% vs 4.9%, p = 0.002). The proportion of those committed mass murders by other methods who had used, possessed, and/or distributed cannabis did not significantly differ for events that occurred from 1996 onward, compared with prior to 1996 (4.8% vs 5.7%, p = 0.76). When 58 mass shooting events and 31 mass murder events by other methods perpetrated before 1960 were excluded, results were similar when 1996 was used as a cutoff for the respective events (p = 0.02 and p = 0.40). Among those who committed mass shootings, those with cannabis involvement (n = 74) were younger than those without (n = 754) [28.7 vs 33.5 years, p < 0.001] and were of younger age group than older age group (11.9% vs 5.8%, p = 0.002).

Conclusion: Cannabis use may be harmful in subgroups of individuals (eg, those who committed mass shootings) who are vulnerable to cannabis use. This should be considered by policymakers, individuals with commercial interests, the public, and mental health and medical professionals when they debate related public health issues.

Ragy R Girgis, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, United States

Hannah Hesson, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, United States

Paul S Appelbaum, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, United States

Gary Brucato, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, United States

Address for correspondence: Dr Ragy R Girgis, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, United States. Email: ragy.girgis@nyspi.columbia.edu

Submitted: 16 December 2024; Accepted: 6 February 2025

Introduction

In the United States, the annual rate of mass shootings increased from nine in 1980 to 40 in 2019.1,2 Commonalities among those who perpetrate mass shootings include childhood trauma (eg, neglect or exposure to violence at a young age), crisis (usually within the weeks or months before an event, leading to a change in behaviour or a threat), a need for validation (eg, notoriety, radicalisation, blaming others), and access to firearms.1 Additionally, cannabis use has become more prevalent and socially acceptable,3,4 partly due to the legalisation of medical cannabis in California since 1996 and of recreational cannabis in Colorado and Washington since 2012, both of which may affect perceptions of cannabis in the United States as a whole.5-7 Substance use is associated with mass violence,2,8 and cannabis use in particular is associated with impulsivity9 and violence.10 We aimed to examine cannabis involvement among those who committed mass shootings in the United States from 1900 to 2019.

Methods

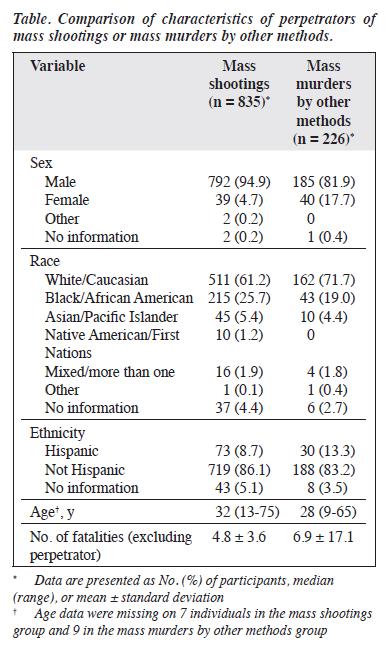

We identified mass shooting events in the United States from 1900 to 2019 using publicly available English-language media reports and court/police records. Mass shooting events were defined as murders perpetrated using at least one firearm and involving ≥3 non-perpetrator fatalities within 7 days. Perpetrators were coded as either having or not having a reported history of use, distribution, and/ or possession of cannabis. People who perpetrated mass murders using methods other than firearms (eg, knives, automobiles) were used as a comparison group (Table).

Events were dichotomised into either prior to 1996 or from 1996 onward. We chose 1996 as a cutoff because it is a watershed moment; decriminalisation of cannabis began in the 1970s, followed by its first legalisation for medical use by California in 1996. Post-1960 data were used for additional analyses of a more modern era.

Analyses were conducted using the 2×2 (time period by cannabis status) Chi-squared test of association and repeated for each type of event using 1990 and 2000 as cutoff years to capture the first full decades before and after medical cannabis legalisation, respectively. Although a more granular temporal analysis was considered, the relative rarity of mass murder events over time necessitated the broader analytic approach. Any association between age and mass shootings or cannabis use was determined using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Chi-squared test using a median split of 32 years.

Results

The proportion of those who committed mass shootings who had used, possessed, and/or distributed cannabis was significantly higher for events that occurred from 1996 onward, compared with prior to 1996 (11.2% [59/529] vs 4.9% [15/306], χ2(1) = 9.38, p = 0.002). Similar effects were seen for events that occurred prior to 1990, compared with from 1990 onward (3.7% vs 10.6%, χ2(1) = 9.48, p = 0.002) and for events that occurred prior to 2000, compared with from 2000 onward (6.2% vs 11.3%, χ2(1) = 6.71, p = 0.01).

The proportion of those committed mass murders by other methods who had used, possessed, and/or distributed cannabis did not significantly differ for events that occurred from 1996 onward, compared with prior to 1996 (4.8% [5/104] vs 5.7% [7/122], χ2(1) = 0.0966, p = 0.76). When 58 mass shooting events and 31 mass murder events by other methods perpetrated before 1960 were excluded, results were similar when 1996 was used as a cutoff for the respective events (p = 0.02 and p = 0.40). Among those who committed mass shootings, those with cannabis involvement (n = 74) were younger than those without (n = 754) [28.7 vs 33.5 years, p < 0.001] and were of younger age group than older age group (11.9% [51/428] vs 5.8% [23/400], χ2(1) = 9.66, p = 0.002).

Discussion

In the United States, the percentage of those who committed mass shootings and had a history of cannabis involvement has increased; this relationship is correlational rather than causal. Indeed, there is evidence of the potential therapeutic characteristics of cannabis11 and a reduction in crime when adding a dispensary to a neighbourhood.12 These findings are consistent with those in previous studies that demonstrate relationships between cannabis use and violence, especially among adolescents and young adults.10,13,14 However, there is a possibility that cannabis use directly increases violent behaviours among certain individuals. There is robust evidence for an association between violence and cannabis use,10,13,14 but causal associations are difficult to establish. Postulating a causal association may be inconsistent with the decline in overall violent crime rates in the decades since cannabis legalisation. This suggests that cannabis-related mass murders may be more likely as a result of disputes over illegal sales of cannabis than a direct effect of the drug.

Another possible explanation is that the association between cannabis and violence, particularly in mass shootings, is mediated by the effects of cannabis use on suicidal behaviours. There is a strong association between the perpetration of public (rather than private) mass shootings and suicide. Indeed, the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation among people who commit mass shootings is as high as 70% in the United States.15 The incidences of suicide and suicidal thoughts among mass shooters are very high.1,15,16 Chronic cannabis use may increase the risk of suicidal ideation,17 particularly among males18 who are often the perpetrators. Suicidal ideation is particularly relevant to mass shootings given that approximately half of suicides involve firearms.19 The extent to which suicidal ideation may mediate the association between cannabis involvement and violence (and, specifically, mass shootings) is not clear. The current findings only observed a significant association between cannabis involvement and mass shootings but not mass murders by other methods. These two groups of perpetrators have multiple demographic differences.2 Although only approximately 5% to 7% of mass shootings are directly related to psychosis,20 the association between cannabis and mass shootings may be due to cannabis being a risk factor for thought disorder.21 Cannabis involvement may therefore be only an indirect risk factor for mass shootings.

States that have legalised cannabis demonstrate higher rates of cannabis use.22 Cannabis use disorders have increased after legalisation among both younger and older individuals.23 Legalising cannabis is associated with an increased prevalence of driving under the influence of cannabis, but not alcohol,24 and traffic fatalities in Colorado.25 There is no increase in cannabis use among adolescents.26-28 There is small to no effect of cannabis laws on rates of violent and property crime.29,30 It remains unclear whether the potential adverse effects of cannabis are a result of availability, potency, product, or any other related characteristic.

Our findings are subject to several limitations. There is a potential bias associated with the sources of data (ie, media reports and court/police records). First-hand prospective sources of data would have been ideal but were not available. The sample size is relatively small. Although a large sample of mass murder events was collected, the rarity of such events limits our ability to assess state-by- state heterogeneity with regard to cannabis status, rendering simple dichotomisation of cases using a cutoff of the legalisation in 1996. Furthermore, we could only use any type of involvement with any type of cannabis product as a binary variable because the nature and degree of use by many perpetrators could not be determined. For example, we could not distinguish between individuals who used cannabis recreationally, those who used it for medicinal purposes, or those who met the criteria for a cannabis use disorder. Additionally, our findings could primarily reflect differences in reporting by individuals or the media rather than actual involvement; we attempted to account for these confounders by including a non-firearm mass murder comparison group. We also did not examine relationships between cannabis involvement and involvement with other substances or adverse childhood experiences due to a paucity of data. Cannabis may not play a causal role but rather act as an indicator of the presence of the actual causal variable. Despite these limitations, inclusion of a non-firearm comparison group to limit the effects of confounding variables and the relatively large sample of the events provides some basis for future investigation.

Conclusion

Although many individuals can be involved with cannabis without risk to themselves or others, cannabis use may be harmful in subgroups of individuals (eg, those who committed mass shootings) who are vulnerable to cannabis use. This should be considered by policymakers, individuals with commercial interests, the public, and mental health and medical professionals when they debate related public health issues.

Contributors

All authors designed the study and analysed the data. RRG, HH, and GB acquired the data. RRG drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

RRG receives compensation for expert consulting for Noble Insights, Signant Health, Guidepoint, Clearview Healthcare Partners, Health Monitor, and IMS Consulting and Expert Services, as well as royalties from books on mental health published by Wipf and Stock and Routledge/ Taylor and Francis. He also provides expert legal consulting for individual law firms. GB receives royalties and/or advances from the books The New Evil: Understanding the Emergence of Modern Violent Crime from Rowman & Littlefield and Understanding and Caring for People with Schizophrenia: Fifteen Clinical Cases from Routledge/ Taylor and Francis. He participates in a Boston College Connell School of Nursing Innovation Grant and is on the expert forensic panel for the Cold Case Foundation. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Peterson J, Densley J. The Violence Project Database of Mass Shootings in the United States, 1966-2019. Accessed 16 December 2024. Available from: https://www.theviolenceproject.org.

- Brucato G, Appelbaum PS, Hesson H, et al. Psychotic symptoms in mass shootings v. mass murders not involving firearms: findings from the Columbia mass murder database. Psychol Med 2021:1-9.

- Hasin D, Walsh C. Trends over time in adult cannabis use: a review of recent findings. Curr Opin Psychol 2021;38:80-5.

- Patrick ME, Pang YC, Terry-McElrath YM, Arterberry BJ. Historical trends in cannabis use among U.S. adults aged 19-55, 2013-2021. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2024;85:477-86.

- Hasin DS, Wall MM, Choi CJ, et al. State cannabis legalization and cannabis use disorder in the US Veterans Health Administration, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Psychiatry 2023;80:380-8.

- Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, Hughes A. Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002-14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:954-64.

- Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Sarvet AL. Time trends in US cannabis use and cannabis use disorders overall and by sociodemographic subgroups: a narrative review and new findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2019;45:623-43.

- Meloy JR, Hempel AG, Mohandie K, Shiva AA, Gray BT. Offender and offense characteristics of a nonrandom sample of adolescent mass murderers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:719-28.

- Solowij N, Jones KA, Rozman ME, et al. Reflection impulsivity in adolescent cannabis users: a comparison with alcohol-using and non-substance-using adolescents. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;219:575-86.

- Dellazizzo L, Potvin S, Dou BY, et al. Association between the use of cannabis and physical violence in youths: a meta-analytical investigation. Am J Psychiatry 2020;177:619-26.

- Betthauser K, Pilz J, Vollmer LE. Use and effects of cannabinoids in military veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2015;72:1279-84.

- Brinkman J, Mok-Lamme D. Not in my backyard? Not so fast. The effect of marijuana legalization on neighborhood crime. Reg Sci Urban Econ 2019;78:1-23.

- Dellazizzo L, Potvin S, Athanassiou M, Dumais A. Violence and cannabis use: a focused review of a forgotten aspect in the era of liberalizing cannabis. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:567887.

- Schoeler T, Theobald D, Pingault JB, et al. Continuity of cannabis use and violent offending over the life course. Psychol Med 2016;46:1663- 77.

- Lankford A, Silver J, Cox J. An epidemiological analysis of public mass shooters and active shooters: quantifying key differences between perpetrators and the general population, homicide offenders, and people who die by suicide. J Threat Assess 2021;8:125-44.

- Lankford A. Identifying potential mass shooters and suicide terrorists with warning signs of suicide, perceived victimization, and desires for attention or fame. J Pers Assess 2018;100:471-82.

- Borges G, Bagge CL, Orozco R. A literature review and meta-analyses of cannabis use and suicidality. J Affect Disord 2016;195:63-74.

- van Ours JC, Williams J, Fergusson D, Horwood LJ. Cannabis use and suicidal ideation. J Health Econ 2013;32:524-37.

- Mann JJ, Michel CA. Prevention of firearm suicide in the United States: what works and what is possible. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:969- 79.

- Brucato G, Hesson H, Dishy G, et al. An analysis of motivating factors in 1,725 worldwide cases of mass murder between 1900-2019. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2023;34:261-74.

- Hasan A, von Keller R, Friemel CM, et al. Cannabis use and psychosis: a review of reviews. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020;270:403- 12.

- Cerda M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin D. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;120:22-7.

- Cerda M, Mauro C, Hamilton A, et al. Association between recreational marijuana legalization in the United States and changes in marijuana use and cannabis use disorder from 2008 to 2016. JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77:165-71.

- Fink DS, Stohl M, Sarvet AL, Cerda M, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Medical marijuana laws and driving under the influence of marijuana and alcohol. Addiction 2020;115:1944-53.

- Santaella-Tenorio J, Wheeler-Martin K, DiMaggio CJ, et al. Association of recreational cannabis laws in Colorado and Washington state with changes in traffic fatalities, 2005-2017. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:1061-8.

- Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Fink DS, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2018;113:1003-16.

- Anderson DM, Hansen B, Rees DI, Sabia JJ. Association of marijuana laws with teen marijuana use: new estimates from the youth risk behavior surveys. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173:879-81.

- Keyes KM, Wall M, Cerda M, et al. How does state marijuana policy affect US youth? Medical marijuana laws, marijuana use and perceived harmfulness: 1991-2014. Addiction 2016;111:2187-95.

- Lu R, Willits D, Stohr MK, et al. The cannabis effect on crime: time- series analysis of crime in Colorado and Washington state. Justice Q 2019;38:565-95.

- Harper AJ, Jorgensen C. Crime in a time of cannabis: estimating the effect of legalizing marijuana on crime rates in Colorado and Washington using the synthetic control method. J Drug Issues 2023;53:552-80.