East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2010;20:23-30

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Alfert WK Tsang, MBBS, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, Kowloon Hospital, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China.

Dr Roger MK Ng, Department of Psychiatry, Kowloon Hospital, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China.

Dr KC Yip, Department of Psychiatry, Kowloon Hospital, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Alfert Wai-kiu Tsang, Department of Psychiatry, Kowloon Hospital, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 3129 7111; Fax: (852) 3129 6442; Email: tsanghy@ha.org.hk

First submission: 27 November 2008; Resubmission: 19 May 2009; Accepted: 23 June 2009

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the effects of the ‘clubhouse’ model of rehabilitation on various psychosocial issues for Chinese patients with schizophrenia living in the community.

Methods: A longitudinal, case-controlled and naturalistic design was used. A total of 92 participants were recruited via criteria-guided systematic sampling for a study lasting 6 months. Forty-six participants attending a local clubhouse programme were matched for sex and age with a control group of patients recruited from a regional outpatient clinic who were not attending a clubhouse programme. Case note reviews, standardised assessments of psychotic symptoms, depressive symptoms, quality of life, self- esteem, and locus of control were performed at baseline, 3 and 6 months.

Results: Clubhouse participants showed significant improvements in their positive and negative scales, general psychopathology, and total scores after attending the clubhouse for 6 months. The clubhouse participants’ employment rate also improved.

Conclusion: The clubhouse model of rehabilitation may have beneficial effects on various psychiatric symptoms in Chinese patients with schizophrenia living in Hong Kong.

Key words: Community mental health services; Employment, supported; Program evaluation; Quality of life

摘要

目的:检视本地华籍精神分裂症患者透过「会所模式」运作的精神病患者复康计划於各项社会心理因素达至的效果。

方法:这项纵向病例对照自然研究以精神分裂症诊断标準,并利用系统抽样方式选出92名患者参与,为期6个月。患者分成两组,包括46名参与此复康计划的患者,以及46名性别和年龄相互配合、来自地区门诊诊所的患者作对照组,分析他们在计划开始时、计划进行3个月和6个月後的病历记录回顾、精神病症状规範评估、压抑症状、生活质素、自尊心水平和控制点。

结果:计划进行6个月後,患者在阳性与阴性症状、一般心理病理状况表现和总得分皆显著改善;就业率也有所增加。

结论:「会所模式」复康计划有助改善本地华籍精神分裂症患者的各种精神病症状。

关键词:社区精神健康服务、辅助就业、计划评估、生活水平

Introduction

The ‘clubhouse model’ is a psychiatric rehabilitation system providing social, educational, and vocational training for adults recovering from chronic mental illness.1 It facilitates consumer empowerment and has become an option in the community rehabilitation of patients with schizophrenia in Hong Kong.2 Consumer empowerment is an important element of rehabilitation for people with schizophrenia as empowered patients have better self-esteem,3,4 better quality of life,3-5 fewer psychotic symptoms,6 and fewer depressive symptoms.7

Work is the main tool used for achieving rehabilitation in the clubhouse model8,9 and the 3 keystones of this model are meaningful relationships, meaningful work tasks, and a supportive environment.8 Clubhouse membership is voluntary10 and the members have free choice over their use of the service.11 Member and staff relationships develop through the work they do together in a work unit in the clubhouse, which has structured daily activities called ‘the work-ordered day’ to maintain the clubhouse function.12 Clubhouse members also join various types of employment training like transitional employment / group transitional employment, supported employment, independent employment, and group placement. The clubhouse also provides recreational programmes, an outreach service and community support for its members. All members and professional staff have equal authority to operate the programme and are considered co-providers.11

Several studies have investigated the clinical benefits of the clubhouse model. Case-controlled and longitudinal studies have found that clubhouse members adhere better to psychiatric medication13 after attending a clubhouse programme for 6 months and have shorter inpatient stays.13,14 Clubhouse members were also found to have a better quality of life5,15,16 and better social functioning, better emotional-coping abilities and work personalities2 in longitudinal and case-controlled studies on patients attending clubhouse programmes for 3 to 12 months. A longitudinal study showed that patients with schizophrenia who attended a clubhouse programme for 8 months had fewer positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia.16

Methods

This study aimed to investigate the effects of the clubhouse rehabilitation model on the psychosocial functioning of Chinese patients with schizophrenia. This was a longitudinal, case-controlled and naturalistic study using a matched sampling method. Measurements were taken at baseline, then at 3 and 6 months after the intake.

Subject Recruitment

There were 2 groups of participants in this study. The experimental group comprised participants joining the Kapok Clubhouse aged 18 to 60 years, and had a 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnosis of schizophrenia. The control group were people with schizophrenia attending a regional outpatient clinic. They were selected from the clinic’s computerised database, which has basic clinical and demographic details of all outpatients. The control participants were matched with the experimental group for gender and age. The ICD-10 diagnoses of schizophrenia were made by consensus between the referring psychiatrists and the principal investigator. Participants with mental retardation, organic brain disorder, substance or alcohol abuse, depressive disorder, post-schizophrenic depression, and personality disorder were excluded. Participants who had had their medication adjusted or had required structured psychological intervention within the previous 3 months were also excluded.

Measurement Instruments

Demographic and clinical variables were obtained at the beginning, and at 3 and 6 months during the study. Relapse of schizophrenic illness was defined as admission to psychiatric hospital or day hospital; and / or a step-up of antipsychotic medication or an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms as verified by an outpatient case note review. Below are the instruments used in this study.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)17 consists of thirty 7-point items, rated from 1 (absent) to 7 (extremely severe), and is used according to standard instructions to measure psychotic symptoms. There are 7 items in the positive subscale, 7 items in the negative subscale, and 16 items in the general psychopathology subscale. The Cronbach’s alphas were 0.7 for the positive subscale, 0.8 for the negative subscale, and 0.8 for the general psychopathology subscale.

The Chinese Version of the Beck Depression Inventory

The Chinese version of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI- II)18,19 is a 21-item self-reported rating inventory measuring characteristic attitudes and depressive symptoms.18 The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.9.

The Chinese Version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life–Brief Version

The Chinese version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life, brief version (WHOQOL-BREF-HK) is a self-administered questionnaire measuring the quality of life in relation to health and health care.20 It consists of 28 questions on a 5-point scale measuring the physical, psychological, psychological-HK (same as the psychological domain except that it has 2 additional questions concerning “eating” and “being respected and accepted”), social relationships, and environmental domains of quality of life. The Cronbach’s alpha for the various domains measured by this tool ranged from 0.7 to 0.8.

The Chinese Version of the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale

The Chinese version of the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale is a validated scale with 10 questions measuring participants’ self-esteem. A higher score indicates a higher level of self-esteem. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.8.

The Chinese Version of the Levenson Internality, Powerful Others and Chance Scale of Locus of Control

The Chinese version of the Levenson Internality, Powerful Others and Chance Scale of locus of control (IPC) consists of 24 items with 3 subscales: the Internal scale (I scale), the Powerful Others scale (P scale), and the Chance scale (C scale). It assesses the locus of control of the participants.21,22 Participants rated each item on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from -3 to 3. The I scale measures the extent to which one believes that one has control over one’s life, and a high score indicates that the participant expects to have control over his own life. The P scale is concerned with the belief that other people control the events in one’s life, and a high score indicates that powerful others have control over one’s life. The C scale measures the degree to which one believes that chance affects one’s experiences and outcomes, and a high score indicates that the participant expects chance forces (luck) to have control over his / her life. The Cronbach’s alphas for the I, P, and C scales were 0.6, 0.8, and 0.8 respectively.

Clubhouse Facilities and Rehabilitation

This study was conducted at a regional outpatient clinic and a local clubhouse (Kapok Clubhouse) in Hong Kong. The clubhouse accepts referrals from various disciplines and walk-in applications from psychiatric outpatients over the age of 16 years. It opens from 9 am to 6 pm from Mondays to Fridays. Members undergo transitional employment, supported employment, independent employment, and group placement training from time to time. It has 2 work units and provides a work-ordered day programme involving gardening, catering, clerical and administrative work for its members. All members are able to choose the work they want. Members also organise evening, weekend, and holiday programmes regularly. During the study period, there were 3 full-time staff and about 50 members attending the clubhouse each day. The Kapok Clubhouse was not a certified clubhouse at the time of the study.

The quality and fidelity of this clubhouse service were assessed by an independent psychiatrist 3 months after this study commenced, using the International Center for Clubhouse Development Clubhouse Research and Evaluation Screening Survey (CRESS).23 This scale consists of the Explicit Item subscale measuring 17 core indicators, and the Indicator Item subscale measuring 42 secondary indicators. The cut-off points for being considered a clubhouse providing a quality service were 16 points for the Explicit Item subscale and 33 points for the Indicator Item subscale.

Statistical Analyses

The data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Windows version 13.0. Categorical data were analysed using Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data were examined using paired Student’s t tests. Non-parametric tests were used when the data were not distributed normally. A 2-way analysis of variance using repeated measures with a Bonferroni correction was used to test the differences between various continuous measures. All missing data were accounted for by using an intention-to-treat analysis.

Results

Quality of the Clubhouse

The CRESS assessment of the Kapok Clubhouse yielded an Explicit Item score of 16 and an Indicator Item score of 33, suggesting that the Kapok Clubhouse was meeting the basic service standards expected by international authorities at the time of the study.

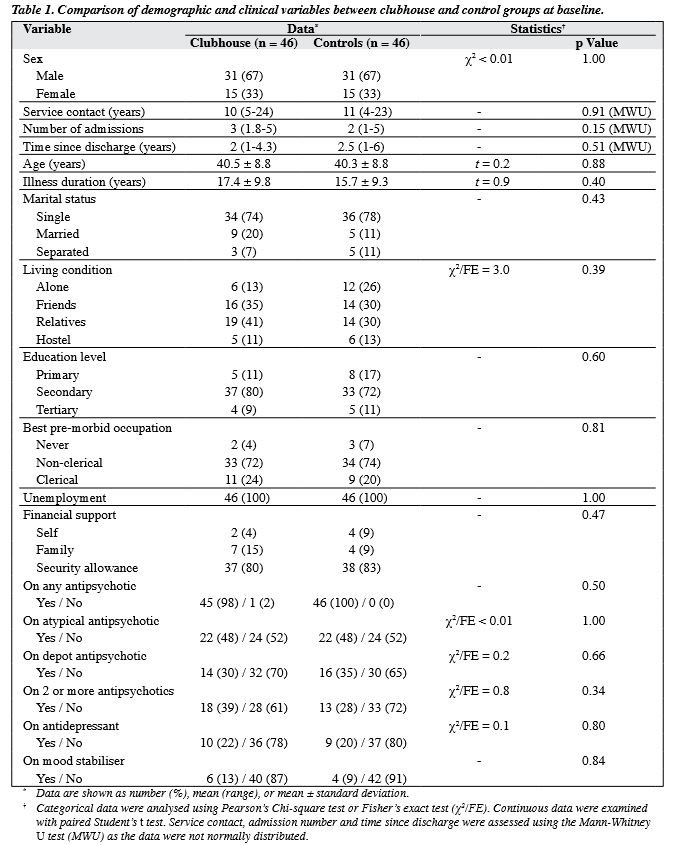

Baseline Demographics, Types, and Dosage of Psychotropic Medication

A total of 92 participants (46 matched pairs) were recruited. Both groups had similar demographic and clinical variables (Tables 1 and 2). Both groups had similar types and average dosages of medication at baseline. The average antipsychotic medication dosage, expressed as a chlorpromazine equivalent, was 289.4 mg for the experimental group and 296.6 mg for the control group.

Baseline Clinical Variables

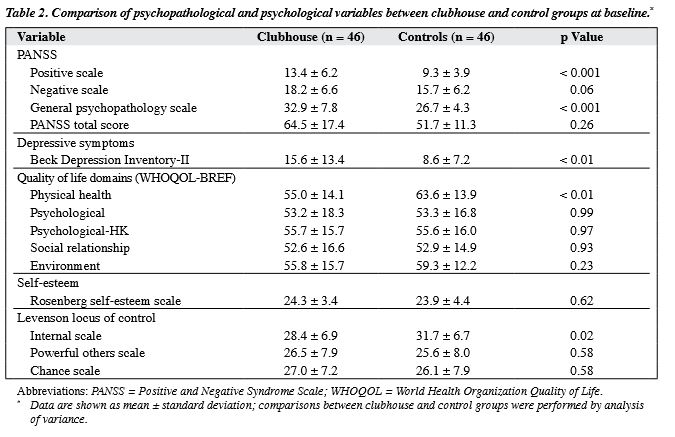

The baseline results indicated that the clubhouse participants had significantly higher PANSS positive subscale score (F = 3.8, p < 0.001), PANSS general psychopathology subscale score (F = 4.7, p < 0.001), and BDI score (F = 3.1, p < 0.01). The clubhouse participants also scored lower in the physical health–related quality of life (F = 2.9, p < 0.01) and in the internal locus of control (F = 2.3, p = 0.02) [Table 2].

Dropout Rate and Attendance Rate at Six-month Follow-up

Eighty participants (87%) completed the study — 39 from the clubhouse group and 41 from the control group were assessed at 6 months; 4 participants dropped out from each group, and 3 in the clubhouse group and 1 in the control group refused to complete the study. There was no difference in the dropout rate between the 2 groups, and no change in the demographic variables of both groups. The experimental subjects had an overall average attendance rate of 37.3% per month during the study period, whereas the average attendance rate for the members of Kapok Clubhouse was around 40% per month during the study period, but with a statistically insignificant difference.

Three-month and Six-month Relapse Rates

Four participants in the experimental group relapsed, including 1 who had dropped out of the study; 2 were admitted to hospital and 1 received increased medication. Their attendance rates were less than 8.3% per month. Five participants in the control group relapsed: 3 had their medication dosage increased because of an exacerbation of their symptoms of schizophrenia, 1 was hospitalised, and 1 was admitted to the day hospital. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the difference in the experimental- and control- group relapse rates and it was found to be statistically insignificant (p = 0.73).

Six-month Employment Status

Eleven participants in the experimental group were employed at the 6-month follow-up: 4 had attained independent employment, 3 had supported employment, 2 had transitional employment, and 2 had group transitional employment. One control-group member achieved open employment. This difference was assessed using Fisher’s exact test and was statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01).

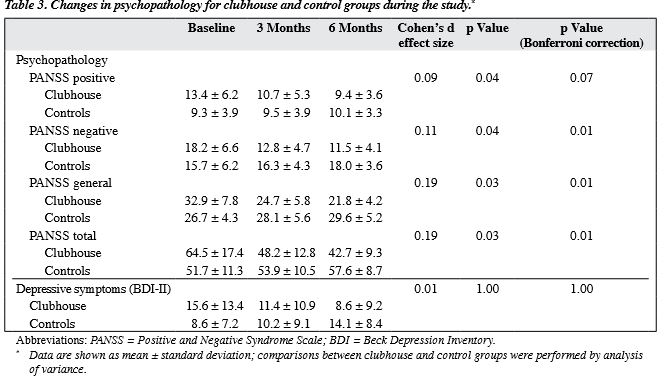

Change in Depressive and Psychotic Symptoms at Six-month Follow-up

At 6 months, PANSS negative, general psychopathology and total scores improved in the clubhouse group, even after Bonferroni correction. The mean clubhouse group’s PANSS negative score decreased from 18.2 to 11.5 while that of the controls increased from a baseline of 15.7 to 18.0 (p = 0.01). The mean clubhouse group’s PANSS general psychopathology subscale score decreased from 32.9 to 21.8, while the controls increased from 26.7 to 29.6 (p = 0.01). The mean clubhouse group’s PANSS total score decreased from 64.5 to 42.7, while that of the controls increased from 51.7 to 57.6 during the study period (p = 0.01) [Table 3].

The BDI-II score decreased from 15.6 to 8.6 in the clubhouse group while in the controls the score increased from 8.6 to 14.1 during the study period; this difference was not statistically significant (Table 3).

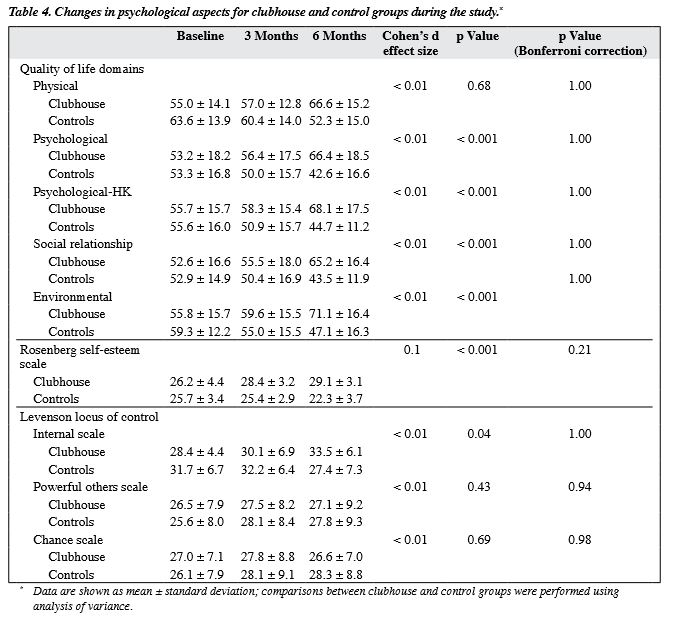

Change in Self-esteem, Locus of Control and Quality of Life Scores at Six-month Follow-up

The 2 groups had similar scores at baseline. At 6 months, clubhouse participants had improved in the psychological, psychological-HK, social relationship and environmental domains of the subjective quality of life score. This difference was not significant after Bonferroni correction (Table 4). The clubhouse group’s self-esteem score also improved from 26.2 to 29.1; the opposite was observed in the control group but this difference was not significant after Bonferroni correction. Regarding the clubhouse group’s locus of control, IPC I scale improved from 28.4 to 33.5 at 6 months and this scale declined in the control group, but the difference was not significant after Bonferroni correction. The 2 groups had similar IPC P scale and C scale throughout the study period (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study there were some small differences in the 2 groups in a few dimensions like psychopathology, mood symptoms, physical health domains, and IPC I scale score.

The clubhouse model of rehabilitation appears to have had a beneficial effect on the psychopathology of the participants. It is interesting to note that the negative symptoms of schizophrenia improved in the clubhouse group. This finding was consistent with that of Yildiz et al.16 This improvement may be related to the process of empowerment via the activities provided by this model.11 The improvement in the group’s general psychopathology and total scores involves improvements in various domains (like mood, guilty feelings, tension, physical condition, anxiety and attention, etc) and provides a separate but parallel measure of the severity of schizophrenic illness that can serve as a point of reference, or control measure, for interpreting the syndromal scores.17

The improvement in participants’ mental state was reflected by the lower number of clubhouse subjects relapsing during the study period, suggesting that the clubhouse model may lower the relapse rate. The exact mechanism is not clear; it might be because the clubhouse members adhered better to their psychiatric medication13 or due to the distraction effect of work,24 though this was not explicitly measured in the current study.

Another important finding from the present study is that the clubhouse participants’ positive symptoms did not worsen after 6 months. This observation suggests that the clubhouse model had minimal adverse effects on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia and the components of this model did not contribute to relapses in schizophrenic patients. The provision of a secure attachment base and the enhanced social support available at the clubhouse might provide a buffer against psychotic relapse.25

The results of this study showed that the clubhouse participants had a higher rate of employment after 6 months. This was consistent with previous studies reporting that clubhouse participants had more favourable work performances.26-29 This is because the work-ordered day provides a real work environment and the clubhouse offers its participants opportunities to work in various categories.30 This finding is of particular importance in the Hong Kong context as patients with mental illnesses like schizophrenia are the least often recruited, even when compared with other disabled people in Hong Kong.31

The transitional employment provided by the clubhouse model allows the participants to have real- life job experiences and this type of employment is more sustainable in the community because of absence coverage.1 Transitional employment circumvents barriers such as a history of psychiatric hospitalisation, poor work history, poor job interview performance, poor work adjustment and poor motivation to work that prevent psychiatric patients from seeking and securing employment.1

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is that it was not a randomised controlled trial, so the effect of the clubhouse model cannot be regarded as definitive. Nonetheless, because the clubhouse model emphasises empowerment and self-determination, it is difficult to envisage how randomisation can be executed without violating these principles. A case-controlled study therefore appeared to be a reasonable alternative. Another major limitation is that assessments were not conducted by blind assessors, thus expectation bias could not be eliminated. Nevertheless, the assessors (the authors) had no allegiance to the clubhouse model and it would have been extremely difficult to blind the assessors. The improvements found by the assessors were actually supported by subjective self-rated assessments, suggesting that the assessor-rated improvement was less likely to be due to expectation bias alone.

Conclusion

This study, performed on a group more disabled at baseline than the control group, suggests that the clubhouse rehabilitation model may be beneficial for Chinese patients with schizophrenia living in Hong Kong. Participants taking part in the clubhouse rehabilitation showed significant improvements in both the objective and subjective indices of psychosocial domains, suggesting that this model may be a valuable intervention for the recovery of patients suffering from schizophrenia in Hong Kong.

Future Research

Randomised controlled trials may be considered to further assess the effectiveness of this model after the clubhouse is certified.

Such a future study may answer some of the concerns raised in this study. Possible research approaches could include dismantling studies examining the effective ingredients of the clubhouse model, qualitative studies identifying the culturally relevant variables believed to be helpful by clubhouse members, the mechanism whereby the clubhouse model leads to improvement in psychotic and depressive symptoms. Whether or not the clubhouse model may confer a long-term beneficial effect on its participants warrants further investigation.

The clubhouse model may be compared with other types of rehabilitation service available in the community so that we may have a better idea of which service is most appropriate for a particular patient.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the patients at the outpatient clinic of the Kowloon Hospital Psychiatric Unit for their inspiration and participation, and her nursing staff for assistance with the study. There was no source of financial support for this study. There is no interest to declare.

References

- Beard JH, Propst RN, Malamud TJ. The fountain house model of psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1982;5:47-53.

- Yau EF, Chan CC, Chan AS, Chui BK. Change in psychosocial and work-related characteristics among clubhouse members: a preliminary report. Work 2005;25:287-96.

- Corrigan PW, Faber D, Rashid F, Leary M. The construct validity of empowerment among consumers of mental health services. Schizophr Res 1999;38:77-84.

- Hansson L, Björkman T. Empowerment in people with a mental illness: reliability and validity of the Swedish version of an empowerment scale. Scand J Caring Sci 2005;19:32-8.

- Rosenfield S, Neese-Todd S. Elements of a psychosocial clubhouse program associated with a satisfying quality of life. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993;44:76-8.

- Lecomte T, Cyr M, Lesage AD, Wilde J, Leclerc C, Ricard N. Efficacy of a self-esteem module in the empowerment of individuals with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999;187:406-13.

- Vauth R, Kleim B, Wirtz M, Corrigan PW. Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2007;150:71-80.

- Norman C. The Fountain House movement, an alternative rehabilitation model for people with mental health problems, members’ description of what works. Scand J Caring Sci 2006;20:184-92.

- Waters B. The work unit: the heart of the clubhouse. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1992;16:41-8.

- Glickman M. The voluntary nature of the clubhouse. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1992;16:39-40.

- Corrigan PW. Enhancing personal empowerment of people with psychiatric disabilities. Am Rehabil 2004;28:10-21.

- Vorspan R. Clubhouse relationships need work! Presented at the 10th International Clubhouse Seminar. Toronto; 1999.

- Delaney C. Reducing recidivism: medication versus psychosocial rehabilitation. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 1998;36:28-34.

- Masso JD, Avi-itzhak T, Obler DR. The clubhouse model: an outcome study on attendance, work attainment and status, and hospitalization recidivism. Work 2001;17:23-30.

- Warner R, Huxley P, Berg T. An evaluation of the impact of clubhouse membership on quality of life and treatment utilization. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1999;45:310-20.

- Yildiz M, Tural U, Kurdoglu S, Emin Onder M. An experience of a clubhouse run by families and volunteers for schizophrenia rehabilitation [in Turkish]. Turk Psikiyatri Derg 2003;14:281-7.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987;13:261-76.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory – II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

- Lu ML, Che HH, Chang SW, Shen WW. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Beck Depression Inventory – II. Taiwanese J Psychiatry 2002;16:301-9.

- Leung KF, Tay M, Cheung S, Lin F. Hong Kong Chinese version World Health Organization Quality of life – abbreviated version. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 1997.

- Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (Chinese version). Taiwan: Yuan-Liou Press; 1997: 551-4.

- Levenson H. Differentiating among internality, powerful others, and chance. In: Lefcourt HM, editor. Research with the locus of control construct. Vol 1. New York: Academic Press; 1981: 15-63.

- Macias C, Propst R, Rodocan C, Boyd J. Strategic planning for ICCD clubhouse implementation: development of the Clubhouse Research and Evaluation Screening Survey (CRESS). International Center for Clubhouse Development. Ment Health Serv Res 2001;3:155-67.

- Van Dongen CJ. Quality of life and self-esteem in working and nonworking persons with mental illness. Community Ment Health J 1996;32:535-48.

- Hultman CM, Wieselgren IM, Ohman A. Relationships between social support, social coping and life events in the relapse of schizophrenic patients. Scand J Psychol 1997;38:3-13.

- Macias C, Rodican CF, Hargreaves WA, Jones DR, Barreira PL, Wang Q. Supported employment outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of ACT and clubhouse models. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1406-15.

- Schonebaum AD, Boyd JK, Dudek KJ. A comparison of competitive employment outcomes for the clubhouse and PACT models. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1416-20.

- McKay C, Johnsen M, Stein R. Employment outcomes in Massachusetts Clubhouses. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2005;29:25-33.

- McKay CE, Johnsen M, Banks S, Stein R. Employment transitions for clubhouse members. Work 2006;26:67-74.

- Vorspan R. Why work works? Psychosoc Rehabil J 1992;16:49-54.

- Ip F, Pearson V, Ho KK, Lo E, Tong H, Yip N. Employment for people with a disability in Hong Kong: opportunities and obstacles. Interim report — employers’ perceptions. Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong; 1995.