East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2010;20:155-62

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr MW Siu, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr TY Cheung, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr MM Chiu, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr TY Kwok, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr WL Choi, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr TK Lo, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr WM Ting, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr PH Yu, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr CY Cheung, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr JG Wong, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr SE Chua, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr MW Siu, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 6130 7821; Fax: (852) 2482 6350; Email: clarasiumw@gmail.com

Submitted: 9 June 2010; Accepted: 3 August 2010

Abstract

Objectives: To explore the preparedness of medical students towards advance directives and related end-of-life issues, and to examine background factors such as knowledge, attitudes, and experience concerning advance directives and related end-of-life issues.

Methods: In 2007, 448 medical students in years 3 to 5 were surveyed at the Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. Their knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of advance directives and related end-of-life issues, and their self-perceived preparedness to discuss these matters with patients were evaluated.

Results: A total of 220 (49%) of the eligible students responded, of whom 79% supported the use of advance directives. Only 65 (30%) students were certain of what advance directives meant and 198 (90%) students felt that their knowledge of advance directives was inadequate. Also, 197 (90%) students felt unprepared about advance directives and end-of-life issues. Factors associated with positive attitude towards advance directives included religion and knowledge. No factors were found to be associated with self-perceived preparedness towards advance directives or end-of-life issues.

Conclusions: Most of the medical students surveyed demonstrated a positive attitude towards advance directives and recognised the importance of advance directives. However, they felt that they were unprepared and lacking in knowledge and experience of advance directives and end-of-life issues. Wider range and more depth of education is needed to better equip medical students for future practice.

Key words: Advance directives; Hong Kong; Living wills; Questionnaires; Students, medical

摘要

目的:检视医科学生对病人临终照顾事项及相关预设医疗指示的準备意识,以及对他们在这方 面的知识、态度和经验等背景因素作出评估。

方法:研究於2007年访问448名香港大学李嘉诚医学院3至5年级医科学生,评估他们对病人治 疗意向和相关临终照顾事项的知识、态度、经验,以及和患者讨论时的自我準备意识。

结果:共220名(49%)合资格学生回应,当中79%认同病人治疗意向的作用。不过,只有 65名(30%)学生明白预设医疗指示的定义,198名(90%)学生对此仍未充份理解;197 名(90%)学生则对预设医疗指示和临终照顾事项未有準备意识。与持积极态度的病人治疗 意向相关因素包括宗教和知识。研究未发现临终照顾与预设医疗指示的自我準备意识相关的因 素。

结论:大部份受访医科学生对预设医疗指示持正面态度,也认同其重要性,却同时承认对此问 题準备意识、知识和经验的不足。为了让医科学生的未来实习作更好装备,相关教育是需要 的。

关键词:病人治疗意向、香港、生前遗嘱、问卷调查、医科学生

Introduction

In general, the concept of advance directives (AD) for health care refers to a statement, usually written, in which a mentally competent individual specifies the form of future health care desired in the event that competence is lacking.1 Legal scholars regard it as an extension of human rights, largely derived from the principles of informed consent and respect for autonomy. The purpose of an AD is to permit the individual to fulfil their goals according to their own value system, and to relieve the family stress. Since the concept of AD in the context of Hong Kong is currently restricted to refusal of life-sustaining treatment, more experience might be required to evaluate whether a wider approach to health care planning is merited in the future.2

From a global perspective, forerunners in the debate on AD include the USA, Canada, and some European nations; to date, all North American states and most Canadian provinces have adopted legislation on AD. While some European states have relatively lower public awareness on AD, some forms of AD are legally recognised in Denmark, the UK, Belgium, France, Spain, Austria, Hungary, and the Netherlands.3 In Australia and New Zealand, AD is now formally recognised under either common law or legislation.3 Singapore has been particularly progressive with AD legislation since 1996.1 It is noteworthy that cultural and religious views impact on decision-making processes in many Asian countries. This can create ambivalence in determining how best to plan future medical care. In Japan, although concerns about AD have arisen in the past decade, a 2003 study of the general population of the preferences and use of AD showed that most participants found it appropriate to express advance health care preferences by word to their family and / or physician, but not by written documentation for cultural reasons. Thus, Japan has no provision for AD or living wills that are legally binding.4 Similarly, in Malaysia, a study of the views of elderly people found that most were receptive to advance care planning and AD, but felt it unnecessary to have formal written documents due to religious beliefs.5

In Hong Kong, it is unsurprising that the issue of AD has been increasingly aired as the community shares multiple health care challenges with its global neighbours, including increased longevity, better education, and shrinking community networks, all of which contribute to the drive for more comprehensive health care planning. In Hong Kong, with its ageing population, there is growing concern about the treatment of terminally ill elderly people and there is a need to further discuss these sensitive issues among health care professionals, policy-makers, and the public.1 Aware of the potential relevance of AD for all stakeholders, the Hong Kong Government started a consultation exercise in December 2009 to explore the concepts and controversies surrounding AD among lay and professional people. Despite legal appreciation of the principles of AD in Hong Kong,6 there has been low use of AD due to lack of knowledge.6 The report concluded that legislation was unnecessary, but as the concept of AD is still new to the community, public education is required.6-8 Perhaps this conclusion was unsurprising, given the dearth of information on AD.9,10

Knowledge and attitudes towards AD among local health care professions remain unclear. Therefore, a study to evaluate attitudes, knowledge, and experience of medical students towards AD was performed. Medical students were selected to participate in the study as these future doctors will play a crucial role in the process. The hypothesis was that background factors would be positively related to the notion of adequate preparedness for AD.

Methods

Participants

In February 2007, 448 medical students from years 3 to 5 at the Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, were invited to complete a questionnaire assessing their knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of AD, and their self-perceived preparedness to discuss AD with patients. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong and Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster.

Questionnaire

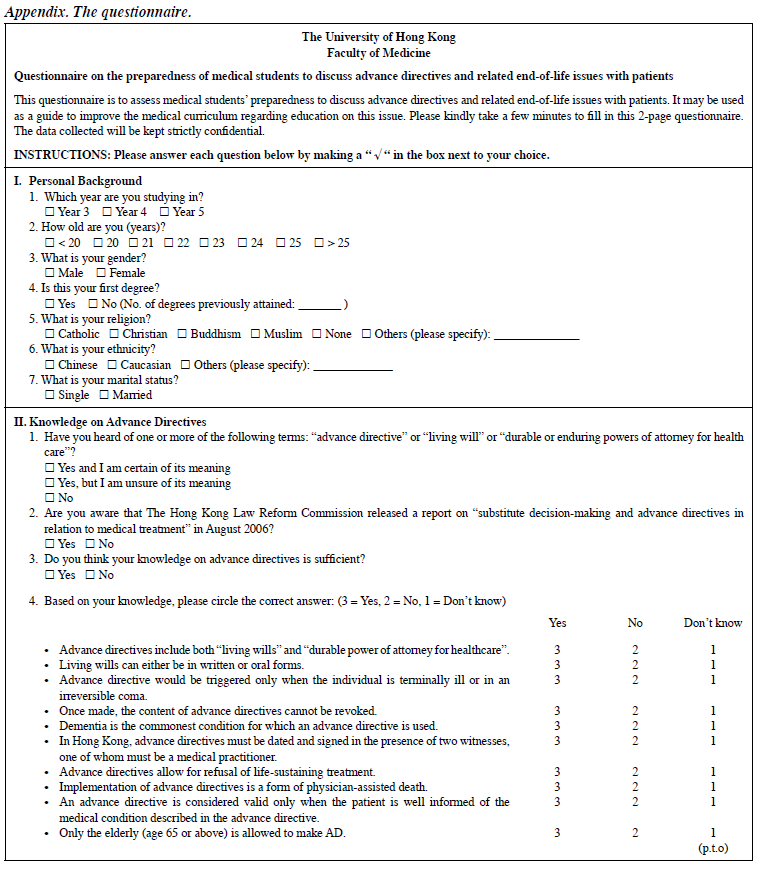

Questionnaires were distributed and collected anonymously, and the students participated on a voluntary basis. The questions were based on a study about preparedness of medical students to discuss AD issues with patients by Buss et al in 1998.11 With permission to adapt the questions granted by the authors, slight modifications were made to accommodate differences in cultural background, medical curriculum of the target group, and development of AD in Hong Kong (Appendix). The questions were reviewed by an expert panel of doctors from the Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine prior to distribution.

The questionnaire consisted of 5 parts of demographic information, attitude, knowledge, experience, and self- perceived preparedness for discussing AD with patients and their families. Demographic data of sex, age, year of study, number of previous degrees, ethnicity, marital status, and religion were collected. Religion was included as it might positively impact on the dependent variables, which were assessed as follows. For knowledge, students’ self- perceived knowledge and actual knowledge of AD were assessed. A series of 10 yes-no questions, derived based on literature review, was utilised to test students’ actual knowledge on AD. Students could answer “yes”, “no”, or “don’t know” for each question. Their level of knowledge was expressed by a maximum score of 10, with 1 mark given to every correct answer. Regarding attitude, 15 statements were posed and included a mixture of statements supporting or opposing AD for which the response was marked on a 5-point Likert scale. For experience, participants were asked to estimate the number of encounters in the following 3 items: discussion of AD with patients; witnessing the discussion of AD; and following up a terminally ill patient. Students were also asked to indicate whether they had witnessed the following 4 end-of-life (EOL) situations: when a patient was pronounced dead; when the family was notified of a patient’s death; a patient’s death during a do-not-resuscitate situation; and when a patient was told of a terminal prognosis. The experience was expressed in a simple score that reflected the exposure of the students to these clinical scenarios. Self-perceived preparedness for discussion of AD with patients and their families was assessed with a series of yes-no questions. Students’ ratings of the usefulness of 7 teaching methods for the education of EOL issues were also assessed using a 5-point Likert scale.

Factors associated with attitudes of medical students towards AD were assessed. Factors evaluated were those related to personal background (sex, academic year, religion), exposure to AD and EOL issues (knowledge, experience) and their self-perceived preparedness.

Statistical Analysis

The data were of categorical (sex, academic year, religion, and self-perceived preparedness) or continuous (age, knowledge, attitude, and experience) type. Chi-square test was used to determine the relationship between categorical variables; linear regression was used to determine the relationship between continuous variables; and independent sample t tests or analysis of variance was used to compare the relationship between categorical and continuous variables. The relationship between personal background (academic year, sex, and religion) and dependent variables (attitude, knowledge, and self-perceived preparedness) was examined, along with the relationship between the 3 factors of attitude, knowledge, and self-perceived preparedness. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Windows version 14.0 software was used for all computations. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

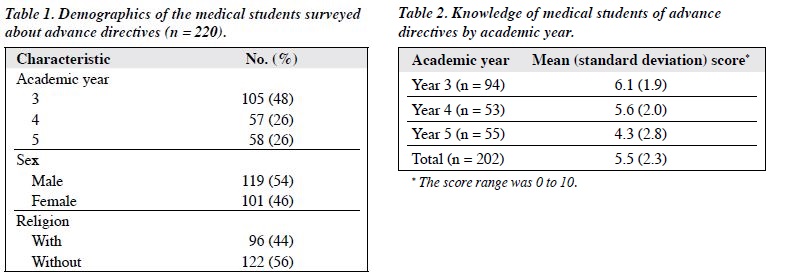

A total of 220 students completed the questionnaire, constituting an overall response rate of 49%. There were no spoiled questionnaires. The response rates by academic year were 78% (105/135) for year 3, 40% (57/142) for year 4, and 34% (58/171) for year 5.

Demographics

In all, 119 respondents (54%) were male and 101 (46%) were female; 105 students (48%) were in year 3, 57 (26%) in year 4, and 58 (26%) in year 5. Most of the respondents were Chinese (n = 216), and the remaining 4 were Caucasian (n = 2), Japanese (n = 1), and Indian (n = 1). Ninety six respondents (44%) were religious (Table 1).

Knowledge of Advance Directives

In all, 170 respondents (77%) had heard of AD, and 65 (30%) were certain of what AD meant. Besides, 56 respondents (26%) were aware of the report Substitute decision-making and advance directives in relation to medical treatment6; 197 students (90%) felt that their knowledge of AD was inadequate.

Students’ knowledge of AD was expressed as a score of 0 for minimum to 10 for maximum. Mean scores are shown in Table 2. In all, 143 students (71%) scored correct in more than 5 questions; 31 students (14%) answered “don’t know” for more than 5 questions, among which 16 (8%) answered “don’t know” for all questions. Higher academic year was associated with poorer knowledge (p < 0.001).

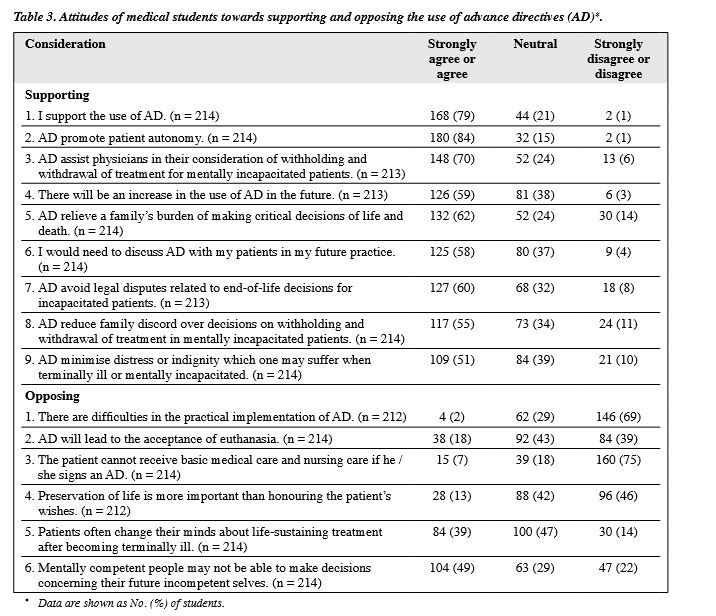

Attitudes towards Advance Directives

In all, 168 students (79%) supported the use of AD and 180 (84%) stated that it promoted patient autonomy. All the statements supporting the use of AD were affirmed by more than half of the students. The 2 major concerns about AD were that patients often change their minds after becoming terminally ill (n = 84; 39%) and mentally competent people may not be able to make decisions for their future selves (n = 104; 49%). When asked whether AD will lead to acceptance of euthanasia, 176 students (82%) either disagreed or remained neutral. Also, 160 students (75%) disagreed with the statement “The patient cannot receive basic medical care and nursing care if he / she signs an AD” (Table 3).

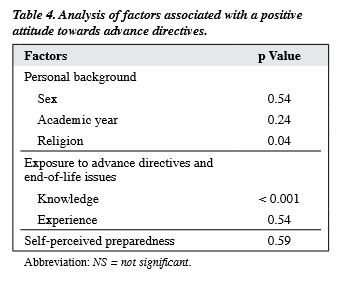

Of the factors associated with attitudes of medical students towards AD, 2 factors identified as significantly associated with positive attitudes towards AD were religion (p < 0.05) and knowledge (p < 0.001). No such relationship was identified for sex, academic year, experience, or self- perceived preparedness (Table 4).

Experience of Advance Directives and Related End- of-life Discussions

Only 1 student (0.5%) had personal experience of discussing AD and related EOL issues with patients (3 times); 14 students (7%) had witnessed AD and related EOL discussions between doctors and patients at least once. The mean number of discussions witnessed by students was 1.6. About half of the respondents (48%) had not encountered any EOL situations.

Self-perceived Preparedness to Discuss End-of-life Issues with Patients

In all, 194 students (88%) felt unprepared to discuss AD with patients; 113 students (51%) felt that there was inadequate exposure and education regarding AD; and 142 students (66%) felt that there were inadequate role models in EOL discussions.

The numbers of students feeling unprepared by year were 117 (87%) in year 3, 132 (93%) in year 4, and 147 (86%) in year 5. There was no significant difference between the years.

Knowledge, attitudes, and experience were not significantly associated with self-perceived preparedness. The lack of association might be attributed to a relatively low response rate by students from years 4 and 5, rendering the samples unrepresentative. To overcome this, the data from year 3 students were extracted and used to re-run the tests, but no significant relationship was found.

Evaluation of Current Medical School Education on End-of-life Issues

In all, 25 students (11%) felt that the education on EOL issues that they received in medical school was adequate to prepare them for future practice, while the rest (89%) were either unsure or felt inadequately prepared. Besides, 104 students (49%) expressed a desire for more education on EOL issues to be included in the medical curriculum.

Assessment of the students’ ratings for the usefulness of 7 educational methods for EOL issues found that the session on medical ethics case discussion and presentation (n = 112, 53%), clinical interpersonal skills (n = 95, 45%) and hospice visits (n = 87, 43%) were considered to be most useful.

Discussion

The results of this study show that most of the medical students had inadequate knowledge of AD. The proportion of students who could define AD was significantly lower in this study than the 61% reported by Buss et al,11 indicating a need to increase their knowledge of AD. This study also found that, contrary to popular belief, higher academic year was associated with poorer knowledge of AD. This may be due to the structure of the current medical curriculum, in which ethics education is mainly conducted during the preclinical years. This finding was counter-intuitive and merits further exploration in future studies. It remains a tentative finding as the proportion of respondents was lowest for the final-year group. Conceivably, the senior medical students may have felt handicapped by their lack of knowledge of the potential ramifications of AD in society, such as political, legal, cultural, and economic factors. Thus, this paradoxical finding may be explained by the possibility that older medical students simply become more cognisant of the complexities of AD, not only in a clinical context, but also in a societal one.

Most students supported the use of AD, and recognised its role in promotion of patient autonomy and assistance in physicians’ consideration of withholding and withdrawal of treatment for mentally incapacitated patients. The finding that 79% of medical students supported the use of AD is comparable to data from Pang et al,9 which targeted the general public and professional nurses (76%), and Lee et al10 which targeted teachers in Hong Kong.

This study found that factors associated with a positive attitude towards AD include religion and knowledge. Various studies have shown that an individual’s preference for AD discussion cannot be predicted by demographic characteristics, including religion.4,10,11 A population-based questionnaire survey about AD conducted in a Japanese community4 and a local study of Chinese teachers’ attitudes towards AD10 revealed a lack of association. Even the study of Buss et al,11 which targeted medical students, did not show this association. The association in this study may be due to the fact that people who have a religious belief would prefer letting nature run its course instead of continuing life- sustaining treatments that may devalue human life.

Knowledge was found to be associated with a positive attitude towards AD. To the authors’ knowledge, no prior report has identified this relationship. It may be that with better knowledge of AD, students realise that it enables patients to have control over their medical care and exercise their autonomy, and removes the uncertainty faced by physicians and family members when making an EOL decision for incapacitated patients.

Students were found to have minimal exposure, inadequate education, and lack of role models for AD and related EOL issues. Moreover, most of the students felt unprepared to discuss AD with patients and families. The findings showed that exposure to AD and related EOL issues were not associated with students’ preparedness. This concurred with the findings of Buss et al,11 who identified a lack of association between exposure to ethics education and preparedness to discuss AD. In contrast, Fraser et al12 reported that the more students participated in EOL educational experiences, the higher their levels of preparation for discussion of EOL with patients. Perhaps the content or format of ethics teaching and pedagogical approaches could account for these discrepancies, since clinical experience and education are intuitively beneficial and worthy of further exploration.

Most Hong Kong medical students felt that they had not received adequate preparation to discuss EOL issues. They expressed a desire for more education on EOL issues to be included in the medical curriculum. A previous study of 262 medical students from 6 medical schools in the USA has yielded similar results, with less than half of the students feeling prepared by their medical education.12

To help optimise the efficacy of future development of the medical curriculum, students’ ratings of the usefulness of the different teaching methods for AD education was explored. The session on medical case discussion and presentation, and clinical exposure such as bedside teaching and hospice visits were considered by medical students to be useful. These results are consistent with the findings of studies conducted among overseas medical students.12,13 Reports in the literature have consistently cited the importance of clinical experience and role models in students’ learning of EOL issues.12-17

This study had 3 principal limitations. First, this was a single-centre study, thus the medical curriculum may not be applicable to other medical students in Hong Kong. Second, the response rate (49%) to the questionnaire was relatively low as it was voluntary and distributed after the lecture sessions. In particular, the response rate was lowest for final-year medical students and might indicate questionnaire fatigue, which would impact the response rate. An attempt was made to ameliorate the uptake rate by means of anonymity, which guaranteed confidentiality. However, it is possible that medical students might be alienated by unfamiliarity with AD and EOL issues. Third, the amount of clinical experience of AD and exposure to related EOL issues were measured retrospectively, based on self-report, and may be subject to recall bias.

Despite these limitations, this study provides an insight into the perspectives of medical students towards AD and related EOL issues. Behind the development of AD is a growing fear of being provided with high-technology treatment to prolong life without consideration of the quality or dignity of life.1 As identified by various studies, physicians rarely discuss AD with their patients.1,11,18-20 Morrison et al20 found that physicians had discussed AD with fewer than 10% of their patients in the previous month. These findings suggest that the problem may begin in medical schools, and students and physicians have remained unprepared.

This is the first study in Asia of medical students’ perceptions of AD. The results show that although medical students are supportive of AD, they do not have sufficient knowledge and are not prepared to discuss AD or related EOL issues. The findings provide an insight into areas of development in the current medical ethics curriculum, implying that greater attention should be given to AD and related EOL discussions. Clinical exposure should be considered a potential area where education of EOL issues could be effectively expanded and reinforced.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Sulmasy and Dr Buss for kindly letting us adapt their paper to the Hong Kong population, and Mr KO Kwok for his statistical advice.

References

- Chiu HF, Li SW. Advance directive: a case for Hong Kong. J Hong Kong Geriatr Soc 2000;10:99-101.

- Hospital Authority Head Office-Operation Circular No.4/2010. Guidance for Hospital Authority clinicians on advance directives in adults. Hong Kong: Working Group on Advance Directives of Hospital Authority Clinical Ethics Committee; March 2010.

- Besirević V. End-of-life care in the 21st century: advance directives in universal rights discourse. Bioethics 2010;24:105-12.

- Akabayashi A, Slingsby BT, Kai I. Perspectives on advance directives in Japanese society: a population-based questionnaire survey. BMC Med Ethics 2003;4:E5.

- Htut Y, Shahrul K, Poi PJ. The views of older Malaysians on advanced directive and advanced care planning: a qualitative study. Asia Pac J Public Health 2007;19:58-67.

- Substitute decision-making and advance directives in relation to medical treatment. Report. HKSAR Government: Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong; 2006. Website: http://www.hkreform.gov.hk/en/docs/rdecision-e.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2010.

- Substitute decision-making and advance directives in relation to medical treatment. Consultation paper. HKSAR Government: Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong Decision-making and Advance Directives Sub-Committee; 2004. Website: http://www.hkreform.gov.hk/en/docs/decision-e.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2010.

- Consultation paper: substitute decision-making and advance directives in relation to medical treatment. Executive summary. HKSAR Government: Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong Decision- making and Advance Directives Sub-Committee; 2004. Website:http://www.hkreform.gov.hk/en/docs/decisions-e.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2010.

- Pang MC, Wong KS, Dai LK, Chan KL, Chan MF. A comparative analysis of Hong Kong general public and professional nurses’ attitude towards advance directives and the use of life-sustaining treatment in end-of-life care. Chinese Medical Ethics 2006;19:11-5.

- Lee JC, Chen PP, Yeo JK, So HY. Hong Kong Chinese teachers’ attitudes towards life-sustaining treatment in the dying patients. Hong Kong Med J 2003;9:186-91.

- Buss MK, Marx ES, Sulmasy DP. The preparedness of students to discuss end-of-life issues with patients. Acad Med 1998;73:418-22.

- Fraser HC, Kutner JS, Pfeifer MP. Senior medical students’ perceptions of the adequacy of education on end-of-life issues. J Palliat Med 2001;4:337-43.

- Wear D. “Face-to-face with It”: medical students’ narratives about their end-of-life education. Acad Med 2002;77:271-7.

- Williams CM, Wilson CC, Olsen CH. Dying, death, and medical education: student voices. J Palliat Med 2005;8:372-81.

- Billings JA, Block S. Palliative care in undergraduate medical education. Status report and future directions. JAMA 1997;278:733-8.

- 16. Ury WA, Berkman CS, Weber CM, Pignotti MG, Leipzig RM. Assessing medical students’ training in end-of-life communication: a survey of interns at one urban teaching hospital. Acad Med 2003;78:530-7.

- Jezewski MA, Brown J, Wu YW, Meeker MA, Feng JY, Bu X. Oncology nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences regarding advance directives. Oncol Nurs Forum 2005;32:319-27.

- Johnston SC, Johnson SC. Advance directives: from the perspective of the patient and the physician. J R Soc Med 1996;89:568-70.

- Hughes DL, Singer PA. Family physicians’ attitudes toward advance directives. CMAJ 1992;146:1937-44.

- Morrison RS, Morrison EW, Glickman DF. Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:2311-8.