East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2010;20:169-73

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr MMC Wong, MBBS, MRCPsych, Castle Peak Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Mimi MC Wong, Castle Peak Hospital, 15 Tsing Chung Koon Road, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 2456 7111; Email: wmc009@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 29 March 2010; Accepted: 18 June 2010

Abstract

Objectives: To examine subjective weight perception of patients with first-episode psychotic disorders, perceived reasons for believing they were overweight, and methods employed for weight reduction (about 1 year) whilst in receipt of antipsychotics.

Methods: A total of 160 consecutive participants with a 1-year history of first-episode psychotic disorders were recruited and their body mass index, subjective weight perception, and the wish to do something about their weight were assessed.

Results: For patients of both genders with first-episode psychotic disorders, weight control behaviours were more associated with the perceived weight status than their actual weight. Most participants who perceived themselves as overweight believed that their weight problem was caused by the antipsychotics they had been taking. Self-reduction of antipsychotics was the commonest method they resorted to in the belief it would result in weight reduction.

Conclusions: There is a need to implement more structured weight loss and physical exercise programmes for patients with first-episode psychotic disorder in order to maintain their physical and mental health.

Key words: Overweight; Psychotic disorders; Weight loss; Weight perception

摘要

目的:检视首发思觉失调患者对体重的主观认知,并分析他们认为超重的原因和在服用抗精神 病药物约一年後使用的减重方法。

方法:共连续招募160名有一年首发思觉失调病史的参与者作研究,并就他们的BMI、主观体重 认知和减重行为作出分析。

结果:不论男女患者,他们的体重控制行为,跟其认知体重的相关性大於其实际体重。大部分 认为自己超重的皆相信这跟服用抗精神病药有关。因此,自行减低服用剂量,是他们认为最有 效减重的方法。

结论:为首发精神病患者提供有效的减重和运动计划,有助他们的生理和心理健康。

关键词:超重、精神失常、减重、重量认知

Introduction

Obesity is highly prevalent among patients with schizophrenia even in the early stage. One study found that more young individuals with psychotic disorders were obese (56%) compared with subjects in the general population (33%).1 Lifestyle, particularly unhealthy eating habits,2 illness-related factors (lack of motivation and poverty), and the use of antipsychotics3 all contribute to the problem. It is important to note that not all overweight individuals are dissatisfied with their weight. On the other hand, not all normal-weight individuals are satisfied with theirs. The determining factor lies on how they perceive their own weight. Weight control behaviours are motivated by perceived weight rather than actual body mass index (BMI).4 This is also true for patients with schizophrenia.5 In a group of young adults with psychotic disorders in Hong Kong, the wish to do something about their weight is closely correlated with how it is perceived.6 The discrepancy between the actual and perceived weight status can lead to harmful unnecessary weight reduction, particularly in persons who perceive being overweight though actually they are not.

The health belief model addresses the effects of beliefs on health and the decision process in making behavioural changes, and has been applied to weight management.7 For subjects to be motivated to change their weight, they need to perceive the severity of their condition and its harmful consequences. Also the perceived reasons for the weight problem and knowledge about weight gain are important, as these will influence the methods used to deal with the problem.

This study aimed firstly to explore subjective perception of body weight status in a group of patients with first-episode psychotic disorders, especially those who perceived themselves as being overweight. Secondly, it set out to examine the reasons they attributed to their perceived overweight status and the methods of weight reduction they used during approximately the first year, whilst on treatment with antipsychotic drugs.

Methods

Participants

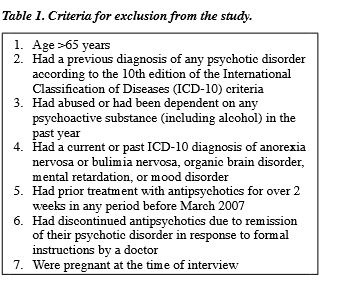

The participants were recruited from the inpatient unit and the outpatient clinics of Castle Peak Hospital, which serves the population of the New Territories West Cluster of Hong Kong, as ascribed by the Hospital Authority. Details of sample recruitment and methodology have been reported elsewhere.8 All eligible patients presenting with a first- episode psychotic disorder between March and December 2007 were approached 10 to 12 months after their diagnosis, with a view to recruitment into the study. Patients were included if: (1) they gave informed consent, were ethnically Chinese, and had adequate command and understanding of Chinese; (2) they had a primary diagnosis under F20-29 according to the l0th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) criteria; and (3) they had taken antipsychotics since their first presentation with acute psychotic symptoms to a psychiatric service for 10 to 12 months before the day of interview. Criteria for exclusion are listed in Table 1. Approval of the New Territories West Cluster Clinical and Research Ethics Committee was obtained before the study commenced. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant. Demographic data were collected and included age, gender, marital status, living status, educational level, and physical health status.

Measurements

The BMI of the participants was calculated using weight and height (rounded up to the nearest 0.1 kilogram and 0.001 metre) in light clothing during the year they were in receipt of antipsychotics. It is generally accepted that the BMI cut-off points defining overweight should be lower for Asians.9 Based on previous local studies, the proposed cut-off point to define overweight for Hong Kong Chinese was 23 kg/m2.10 The BMI was classified into 3 categories: (1) <18.5 kg/m2 as underweight; (2) 18.5 to 22.9 kg/m2 as normal weight; and (3) ≥23.0 kg/m2 as overweight.

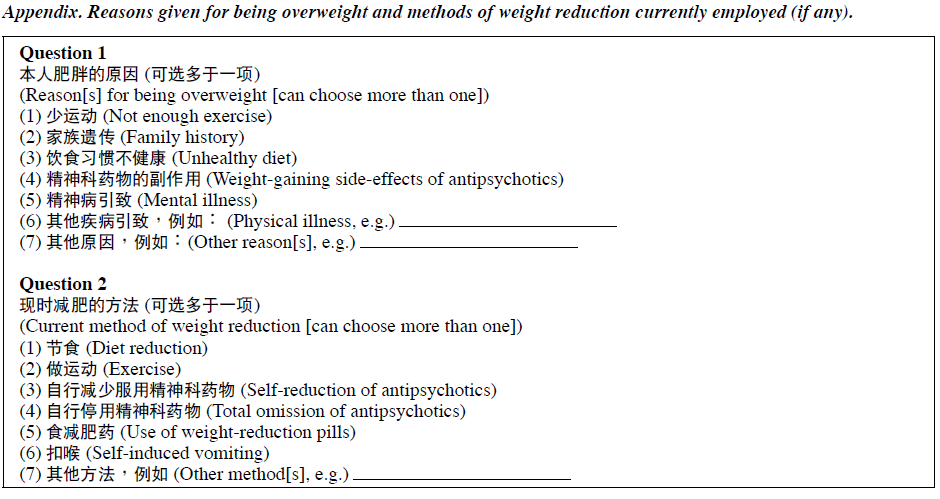

Subjective weight perception was assessed by asking the participants whether they thought they were: (1) underweight; (2) of normal weight; or (3) overweight. The participants were also asked whether they would like to gain weight, remain the same or lose weight. Those who perceived themselves as overweight were asked to what they attributed being overweight and the method they currently employed, if any, to lose weight (Appendix). The participants were given different choices for each of the questions, which were based on a literature review1,3,5 and interviewed with 3 groups of patients with psychotic disorders who attended a talk about weight management. The questions had been revised by an expert panel consisting of consultants, and allied health workers including occupational therapist, a clinical psychologist and a dietician. The questions were pilot-tested on 5 patients who had a primary diagnosis under F20-29 according to the ICD-10 criteria; the test subjects had different educational levels (including only up to primary school level). Practical problems concerning comprehension of the wording were also addressed.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Windows version 16.0. For continuous data, variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SDs) for normally distributed data or as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for skewed data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test for normality. For categorical data, variables were presented as numbers and percentages. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of continuous variables with skewed distributions if there were only 2 groups. For comparison of categorical data, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to test for correlations between continuous variables with skewed distributions.

Results

Participants of the Study

From March to December 2007, 173 patients with psychotic symptoms presenting for the first time and having diagnoses under F20-29 according to ICD-10 were identified. Of these, 5 were excluded: 1 had mental retardation, 2 had depression, and 2 had histories of substance abuse. Of the remaining 168 patients approached 10 to 12 months after their first presentation, 5 more were excluded, because: the diagnosis was changed to organic brain syndrome (n = 1), drug-induced psychotic disorder (n = 1), bipolar affective disorder (n = 2), and discontinuation of antipsychotics (n = 1). Two other patients could not be contacted as they had left Hong Kong immediately after discharge from hospital and were followed up in the United States. One patient refused to be interviewed. There were no statistically significant differences between patients omitted from this study (n = 13) and those who participated (n = 160) in terms of gender (p = 0.87), age (p = 0.35) and baseline BMI (p = 0.45).

The final sample consisted of 160 patients (90 female and 70 male) with a mean (SD, range) age of 30 (11, 14-59) years, and a median (IQR) of 28 (16) years. In all, 86% of the participants had at least 9 years of education, 91% were living with their families, and 79% were unmarried (never married, separated, divorced or widowed). Their diagnoses at the time of the interview included: schizophrenia, delusional disorder, unspecified psychosis, acute and transient psychotic disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. None of them had any medical problem (e.g. endocrine disorder) or took non-psychiatric medications known to affect weight (e.g. steroids and other hormones).

Actual Weight Status

The participants had a median (IQR) current BMI of 22.3 (19.1-25.6) kg/m2; 12% of the participants were underweight, 45% had normal weights and 43% were overweight. The difference in current BMIs between the 2 genders was not statistically significant (p = 0.25). Also there was no significant variation in BMI between different age-groups among both genders.

Perceived Weight Status

The difference in perceived weight status between the 2 genders was statistically significant (p = 0.01); 9% of females and 13% of males perceived themselves to be underweight, 27% of females and 46% of males perceived themselves to be of normal weight, and 64% of females and 41% of males perceived themselves as being overweight.

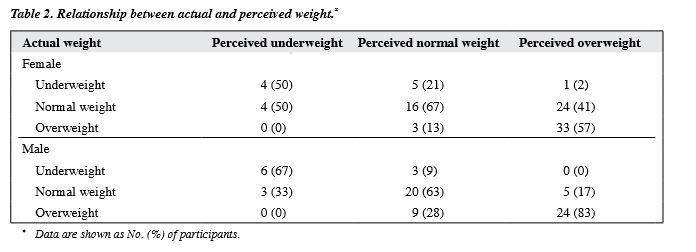

Association between Actual Weight Status, Perceived Weight Status and the Wish to Do Something about Weight

The correlation coefficient (rs) between the actual weight status and the perceived weight status for females was 0.55 (p < 0.001), and for males it was 0.68 (p < 0.001). The relationship between the actual and perceived weight status is shown in Table 2.

The correlation between the wish to do something about their weight status and the perceived weight status was much higher (rs = 0.98, p < 0.001) for females (vs. rs = 0.93, p < 0.001 for males) when compared with that and the actual weight status (rs = 0.54, p < 0.001 for females vs. rs = 0.64, p < 0.001 for males).

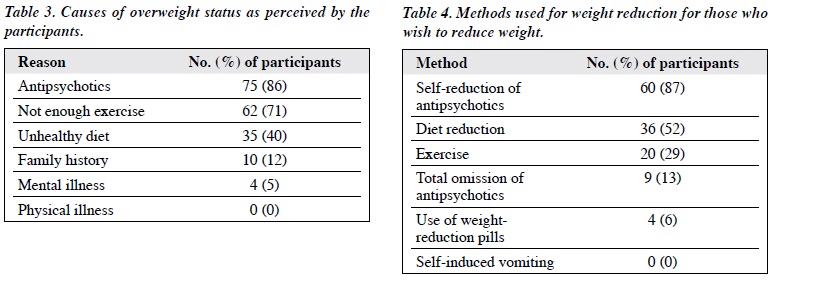

Causes of Overweight Status Perceived by the Participants and Methods of Weight Reduction Employed

The 87 participants who perceived themselves as being overweight were asked about the reasons they thought they were overweight, and were allowed to choose more than 1 option. There were 75 who chose antipsychotics as the cause of their overweight status (Table 3). Among female participants, the 3 most common causes were: antipsychotics alone (n = 15), antipsychotics and not enough exercise (n = 15), and antipsychotics, not enough exercise and an unhealthy diet (n = 15). For the male participants, the 3 commonest causes were: antipsychotics and not enough exercise (n = 11), antipsychotics, not enough exercise and unhealthy diet (n = 4), and not enough exercise and unhealthy diet (n = 4).

Among participants who wanted to reduce their weight, 78% of them (69 / 88) were actually doing something about it. Self-reduction of the dosage of antipsychotics was the most common method resorted to (Table 4). For the female participants, 22 of them chose to reduce via diet together with antipsychotic intake reduction, while 14 chose reduction of antipsychotics as the only method. Among male participants attempting to reduce weight, 11 of them chose to reduce their antipsychotic intake together with exercise, while 8 chose reduction of antipsychotics as the only method.

Discussion

For patients with first-episode psychotic disorders, weight control behaviours in both genders were more associated with the perceived rather than the actual weight status. Female participants in this study tended to overestimate their weight, which is compatible with the weight perception of young adults without mental illness.6 To avoid unnecessary weight reduction, it is therefore important to instil correct weight perception, particularly in females.

Both first- and second-generation antipsychotics are associated with weight gain.3 Indeed most participants who perceived themselves as overweight believed that their weight problem was caused by the antipsychotics they had been taking. In this group of patients, the amount of weight gain after 1 year of antipsychotic treatment was analysed in another study.8 It was not one of the objectives of this study to find out what contributed to their weight problem, however, their subjective association of weight gain with antipsychotics was more important as it is this perception that drives weight reduction behaviour.

Self-reduction of antipsychotics followed by dietary restrictions were the 2 commonest methods used for weight reduction. In a previous study5 it was found that dieting was the primary weight loss measure used by patients with schizophrenia. Self-reduction of antipsychotics was an option in a survey enquiring into weight control methods used in schizophrenia,11 but is seldom condoned. However, weight dissatisfaction has been associated with poor medication adherence.12 It was therefore included as an option in this study. Although there were 62 participants who believed that lack of exercise had resulted in their overweight status, only 20 of them used exercise as a method of weight reduction. By contrast, 4 used weight reduction pills not prescribed by doctors. Education in this area is certainly needed.

Besides providing advice and education on weight reduction, suitable advice about weight control before patients gain weight may be a more effective means, as prevention is always better than cure. Those who work with first-episode psychotic patients may consider intervening early in their illnesses and treatment process. An early behavioural intervention intended to teach strategies to enhance control over factors associated with antipsychotic- induced weight gain was effective in reducing antipsychotic medication–induced weight gain in a cohort of first-episode psychotic patients.13 The aim should be to prevent weight gain. Implementation of a similar programme in this locality could well benefit such patients.

This study had several limitations. First, subjective weight perception was assessed only briefly; being a rather abstract concept it is difficult to assess accurately. However, it was assessed similarly in another study5 looking at body weight perception in patients with schizophrenia. The perceived body weight of the participants was grouped into 3 for convenient comparison with actual body weight. Second, the reasons for weight gain and the means of weight reduction may not include all possible options. However, participants were invited to include their reason and method if these had not been suggested. Third, attempts to lose weight and the methods employed were unconfirmed self-reports. Fourth, we cannot conclude that these findings were unique to patients with psychotic disorders as there was no control group. Lastly, it was surprising that more participants had indicated a reduction of antipsychotic dosage rather than total discontinuation as the method of weight reduction, raising the possibility that they had deliberately chosen a more socially desirable answer. Therefore, although not many participants admitted to omitting antipsychotics totally, underreporting of this option could well be much more prevalent.

Handling weight problems associated with young patients with psychotic disorders is an important issue. There is a need to implement more structured weight loss and physical exercise programmes in this group of patients. Such a strategy could help reduce harmful effects on physical health as well as improve medication compliance.

Acknowledgement

The author declared that there is no financial support and no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- Theisen FM, Linden A, Geller F, Schäfer H, Martin M, Remschmidt H, et al. Prevalence of obesity in adolescent and young adult patients with and without schizophrenia and in relationship to antipsychotic medication. J Psychiatr Res 2001;35:339-45.

- Kurzthaler I, Fleischhacker WW. The clinical implications of weight gain in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62 Suppl 7:S32-7.

- Strassnig M, Miewald J, Keshavan M, Ganguli R. Weight gain in newly diagnosed first-episode psychosis patients and healthy comparisons: one-year analysis. Schizophr Res 2007;93:90-8.

- Cheung PC, Ip PL, Lam ST, Bibby H. A study on body weight perception and weight control behaviours among adolescents in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13:16-21.

- Strassnig M, Brar JS, Ganguli R. Self-reported body weight perception and dieting practices in community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2005;75:425-32.

- Wong MM, Tso S, Lui SS. Accuracy of body weight perception and figure satisfaction in young adults with psychotic disorder in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2009;19:107-11.

- Nejad L, Wertheim E, Greenwood K. Comparison of the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior in the prediction of dieting and fasting behavior. E-Journal of Applied Psychology 2005;1:63-

- Journal website: http://ojs.lib.swin.edu.au/index.php/ejap/article/view/7. Accessed 10 Jul 2007.

- Wong MM. Extent of weight gain in patients with first-episode psychotic disorders after one year of antipsychotic treatment in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2010;20:57-61.

- Pan WH, Yeh WT. How to define obesity? Evidence-based multiple action points for public awareness, screening, and treatment: an extension of Asian-Pacific recommendations. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2008;17:370-4.

- Ko GT, Tang J, Chan JC, Sung R, Wu MM, Wai HP, et al. Lower BMI- cut-off value to define obesity in Hong Kong Chinese: an analysis based on body fat assessment by bioelectrical impedance. Br J Nutr 2001;85:239-42.

- Loh C, Meyer JM, Leckband SG. Accuracy of body image perception and preferred weight loss strategies in schizophrenia: a controlled pilot study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008;117:127-32.

- Weiden PJ, Mackell JA, McDonnell DD. Obesity as a risk factor for antipsychotic noncompliance. Schizophr Res 2004;66:51-7.

- Alvarez-Jiménez M, González-Blanch C, Vázquez-Barquero JL, Pérez- Iglesias R, Martínez-García O, Pérez-Pardal T, et al. Attenuation of antipsychotic-induced weight gain with early behavioral intervention in drug-naive first-episode psychosis patients: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1253-60.