East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013;23:35-6

EDITORIAL

Legislation to allow for the compulsory supervision and treatment of mentally disordered individuals outside hospital has become a feature of several health care systems over the past 30 years. Various terms are used, most frequently mandated outpatient care or community treatment orders (CTOs), which is the term that will be used here. Community treatment orders have been widely introduced in most American states, across Australia and New Zealand and, more recently, in some Canadian Provinces and European countries, with the England and Wales introducing them in 2007. Several Asian legislatures are currently considering their introduction.

The powers of CTOs are generally similar despite often very different descriptions and legal structures. The CTOs provide a legal framework that obliges patients to maintain contact with their clinical team and to take prescribed medication. A power of recall exists if patients fail to meet the terms of their CTO, but none of the legislations allow for physical force to be used outside hospital, indeed all specifically prohibit it. Clearly defined regular monitoring by an independent body and second opinions are features of most regimens. Most CTOs are imposed at the point of discharge after a compulsory admission, although most legislations allow for them to be imposed without such an admission (so-called ‘preventative’ CTOs), but the UK CTO can only be imposed on a legally detained patient (so- called ‘least restrictive’ CTO).

In considering whether to introduce legislation for CTOs, the potential clinical benefits to patients and their families have to be weighed against the undoubted curtailment of liberty in an already marginalised and stigmatised patient group. This editorial will restrict itself to the clinical evidence, which has been excellently summarised in 2 major reviews.1,2 There is certainly no shortage of publications; Churchill et al’s review1 contains 72 studies. Despite this, there is considerable controversy. The evidence can be broadly divided into 3 groups of studies: (1) descriptive and stakeholder trials; (2) database studies; and (3) randomised controlled trials.

Descriptive and Stakeholder Trials

Descriptive and stakeholder trials are well covered in the reviews by Churchill et al1 and Dawson.2 New Zealand and the US dominate in this early literature. In summary, these reviews show that the clinical features of patients subject to CTOs are reassuringly similar across different jurisdictions. Patients are more often men, with about 10 years of psychotic illness (around 80% were schizophrenia in all studies), generally with poor insight, isolated, and at risk of self-neglect. These patients are rarely considered a risk to others. These studies find that carers are generally positive about CTOs. Patients are less positive, but not universally critical, sometimes reporting a sense of security from them and a relief not to be regularly readmitted. Staff, even in legislations where there was initial fierce resistance, rapidly form very favourable opinions and consider them indispensable. Rates of use rise rapidly and reliance on depot medication increases. Many of these early studies claim a reduction in hospital admission based either on a before-and-after or a matched cohort design.

Database Studies

There are 2 significant databases where the association of CTOs with outcomes have been extensively explored. The largest is the Victoria State Database in Australia with data on 16,216 CTOs, and the other is the New York State Database with 3576 CTOs to draw on. There are several publications from each database using a range of methods, of which the commonest is a controlled before-and-after comparison. In these studies, the rates and duration of admissions for a fixed period before and after the imposition of a CTO were compared with a sample (generally much larger) matched at the very least for age, sex, and diagnosis. The Victoria studies generally show an increase in admission (either rates or duration) after the imposition of the CTO,3,4 whereas the New York studies show a reduction.5 The Victoria database is also used to compare patients who receive CTOs early in their psychiatric illness without prior admissions and, not surprisingly, finds that they have fewer admissions compared with those who are given CTOs later in their illness at the point of discharge from compulsory admissions.6

Randomised Controlled Trials

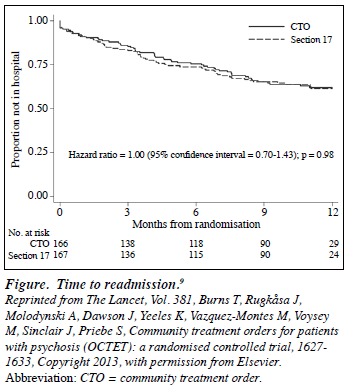

Only 3 randomised controlled trials of CTOs have been published, 2 in the US7,8 and 1 in the UK.9 This low number is unsurprising because of the extra complications of researching a legal provision using the methodology evolved for treatments. These complications are particularly those of negotiating and explaining the legitimacy of randomisation with ethics committees and of reassuring clinicians that they will not be subject to legal challenge. In all 3 trials, the primary outcome measure was the proportion of psychosis patients readmitted to hospital within 12 months. The UK study9 is the largest (n = 333) and, unlike the North Carolina study,7 had no exclusion criteria based on risk of violence and also ensured equivalent rates of clinical contact in the 2 groups (a mean of 3 contacts per month). The complete absence of any impact in the UK trial, despite a mean of 6 months (183 days) with a CTO versus 8 days of prolonged coercion in the control group, is striking. In both groups, 36% of patients were readmitted over the 12-month follow- up period and there was no evidence whatsoever of any delay in readmission with CTOs (Fig9). The median time in hospital did not differ between the groups (41.5 days for CTOs vs. 48.0 days for controls).

Conclusions

Clinical benefit is clearly not the only factor when the introduction of CTOs is being considered. The absence of evidence for effect was well-known and discussed in the UK as the law was being formulated. Legislators consider issues such as public confidence in the mental health services, the persisting exaggerated public assessment of risk from patients with mental illness, and the need to ensure accountability and consistency in mental health care. However, the total absence of any effect in the only 3 rigorous experimental studies must add considerable power to those who argue that this is an intrusion too far into the lives of individuals with severe mental illnesses. Much of the routine work of mental health staff includes supporting and persuading patients to take their treatment, often including various leverages.10 While it is perfectly logical to anticipate that the structure of legal sanction might strengthen this persuasion (‘persuade the persuadable’), the evidence clearly shows that it does not. Legislations considering introducing CTOs would be well advised to pause and consider these findings in some depth.

The 3 randomised controlled trials7-9 should not be ignored by the psychiatric profession. Randomised controlled trials are the accepted gold standard for identifying causality. The evidence is strong and consistent that CTOs do not achieve their primary purpose of reducing readmissions in ‘revolving door’ psychosis patients. Despite the strength of acceptance by families and clinicians, there is clear evidence that CTOs do not benefit psychosis patients, at least in the short term. Given the recognised regression to the mean in long-term outcomes, there is even less reason to believe they will have an effect beyond the 12-month follow-up period used in these trials. Psychiatry has in the past paid a price for persisting with ineffective treatments based on wishful thinking and good intentions. Insulin coma treatment for schizophrenia dominated ‘progressive’ mental hospitals from 1934 until it was finally shown to be utterly ineffective by Ackner et al’s randomised controlled trial in 1957.11 We should not wait so long again to act on clear evidence.

Tom Burns (email: tom.burns@psych.ox.ac.uk)

Professor of Social Psychiatry

University of Oxford

Oxford OX3 7JX

United Kingdom

References

- Churchill R, Owen G, Singh S, Hotopf M. International experiences of using community treatment orders. London: Institute of Psychiatry; 2007.

- Dawson JB. Community treatment orders: international comparisons. Dunedin: Otago University; 2005.

- Burgess P, Bindman J, Leese M, Henderson C, Szmukler G. Do community treatment orders for mental illness reduce readmission to hospital? An epidemiological study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:574-9.

- Segal SP, Burgess PM. Conditional release: a less restrictive alternative to hospitalization? Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1600-6.

- Swartz MS, Wilder CM, Swanson JW, Van Dorn RA, Robbins PC, Steadman HJ, et al. Assessing outcomes for consumers in New York’s assisted outpatient treatment program. Psychiatr Serv 2010;61:976-81.

- Segal SP, Burgess PM. Factors in the selection of patients for conditional release from their first psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1614-22.

- Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, Burns BJ, Hiday VA, Borum R. Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce hospital recidivism? Findings from a randomized trial with severely mentally ill individuals. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1968-75.

- Steadman HJ, Gounis K, Dennis D, Hopper K, Roche B, Swartz M, et al. Assessing the New York City involuntary outpatient commitment pilot program. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:330-6.

- Burns T, Rugkåsa J, Molodynski A, Dawson J, Yeeles K, Vazquez- Montes M, et al. Community treatment orders for patients with psychosis (OCTET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:1627-33.

- Burns T, Yeeles K, Molodynski A, Nightingale H, Vazquez-Montes M, Sheehan K, et al. Pressures to adhere to treatment (‘leverage’) in English mental healthcare. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:145-50.

- Ackner B, Harris A, Oldham AJ. Insulin treatment of schizophrenia; a controlled study. Lancet 1957;272:607-11.