East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013;23:160-3

CASE REPORT

黎狄慈、张颖宗、谭蕴怡、许丽明、陈友凯

Ms Dik-Chee Lai, BSW, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Wing-Chung Chang, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Ms Wendy Wan-Yee Tam, MSocSc, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Christy Lai-Ming Hui, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Prof. Eric Yu-Hai Chen, MA, MBChB, MD, FRCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Ms Dik-Chee Lai, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 2255 4488 / 9468 2635; Fax: (852) 2855 1345;

email: cheeldc@hku.hk

Submitted: 29 November 2012; Accepted: 10 June 2013

Abstract

We report on a woman with first-episode schizophrenia with grandiose delusions. She developed a bizarre delusion that she was ‘Jesus’, who had special powers to talk to animals and predict the future. The grandiose delusions were maintained by her positive emotions, positive imagery of becoming an extraordinary person, and cognitive biases. With the application of cognitive and affective model for formulation of an intervention plan, it was found that the patient had improvement in lowered shamefulness about herself and skills of setting appropriate expectations. The assessment and treatment process of this patient shows the value of applying theory to case formulation and making a care plan for the case management service for patients with first-episode psychosis. This report has clear limitations in that it is a discussion of a single patient, and the case formulation is speculative at this time. The formation and maintenance of grandiose delusions are discussed from the cognitive and affective perspectives.

Key words: Delusions; Psychotherapy; Schizophrenia

摘要

本文报告一名首发精神分裂症与自大型妄想症女患者出现怪异妄想,认为自己是「耶稣」,能 与动物沟通和预知未来。这种自大型妄想症也因患者的正面情绪、想像自己能成为非凡人士, 以及认知偏差而持续。透过认知和情感模型应用而制定的干预计划,患者在羞耻心和设定期望 方面均有所改善。评估和治疗显示把理论应用於病例和对首发精神病患者设计护理计划的重要 性。这宗病例也因只探讨单一患者而呈明显局限性,而且当时制定的治疗方案也是猜测性的。 本文也从认知和情感方面讨论自大型妄想症的形成和持续因素。

关键词:妄想症、心理治疗、精神分裂症

Introduction

Grandiose delusions (GDs) are defined as the false beliefs of having inflated worth, power, knowledge, or a special identity, which are firmly sustained despite undeniable evidence to the contrary.1 Grandiose delusions are the third most common delusions after persecutory delusions and delusions of reference. Ben-Zeev et al2 proposed that GDs may be a more stable state of mind that is predisposed by past life experiences or imaginations, and may be less associated with contextual triggers. It has been postulated that the formation of GDs relates to the developmental trait that predisposes an individual’s reaction to positive affect–triggering events. Negative self-esteem2 and strong positive ideal of self3 may be interacting with each other and contribute to the formation of GDs.

Current psychological studies propose cognitive and affective models in formation and maintenance of delusions.4-8 There is inadequate evidence to conclude that the mechanism of formation of GDs is different from that of the other types of delusions, and it is assumed that the underlying psychological mechanisms are similar. Two major assumptions in delusion formation are the delusion- as-defence (DAD) model4,5,9 and emotion-consistent model.6,10,11

In the context of GDs, the DAD model suggests that an individual may develop GDs to avoid the negative affective consequences of actual ideal self-discrepancies. It has been suggested that GDs may defend against ‘social self-esteem’ or ‘social rank’.7 When people feel endangered in a potentially hostile, rejecting environment, they will be alerted about their relative low rank and lack of power to protect themselves. This triggers various defensive emotions and strategies. Grandiose delusions may develop as defence strategies against being negatively evaluated and the negative affective consequences linking to the perceived threatening interpersonal context.

The emotion-consistent model suggests that the emotional state will drive a search for meaning and understanding that is consistent with the affect. It has been suggested that positive beliefs about self and the associated positive emotions might precipitate the development of GDs.9 The cognitive and information processing biases in relation to pleasurable emotions contribute to the mechanisms of formation and maintenance of GDs.

Garety et al8 suggested a model of positive symptoms of psychosis in which multiple psychological factors are included. More symptom-specific models have been suggested for case formulation, such as the cognitive model of persecutory delusions,6 and the cognitive and affective perspectives on GDs.7 The model for GDs suggested by Knowles et al7 combined both the DAD and emotion- consistent models to address the multiple psychological phenomenon, including cognitive and affective factors. To analyse the psychological mechanism of the formation of this patient’s GDs, the combined model was applied.

Case Report

A 30-year-old woman was referred to the psychiatric service after experiencing an uncontrollable body tremor in March 2010. About 3 months before the referral, the patient’s unstable emotional and mental state was noticed by her mother when the patient experienced uncontrollable somatic discomfort. She associated these unusual experiences with the idea of being possessed by a devil.

The patient described herself as an introverted and timid person with low self-confidence during her childhood and adolescence. She found it difficult to make close friends and was extremely fearful of being humiliated. When she reached early adulthood, it was exceptional that she quickly made friends with a male colleague, whom she met in her first job. This colleague shared with her his beliefs about supernatural power and ways to make money. Under his influence, the patient thought that she would become wealthy and famous in the future. A few months after she started work at the company, she went on a business trip which gave her some positive experiences. Thereafter, she had positive feeling towards herself and thought that she could accomplish everything assigned to her.

One day, the patient saw some flashing images, which she thought related to Jesus. She inferred that she was ‘Jesus’ after attending some augury sessions. She developed a bizarre delusion that she had a special ability to talk to animals and to predict the future. She also heard voices intermittently telling her that she could save the world. Her mother reported no significant mood changes to suggest mood swings or manic episodes such as pressure of speech or unusual increases in energy level. The bizarre delusion was maintained for about 2 years until her place of work closed.

After starting another job, she thought that she had had bad luck and felt that her special ability was diminishing. She was criticised and her job was terminated by another company because of her unsatisfying work performance. Negative emotions developed and her self-esteem was fluctuating.

One year before treatment, she was baptised and she destroyed the augury props. She started to experience uncontrollable somatic discomfort and saw black shadows moving around her almost every day. The content of the voices changed, telling her that she was being possessed. A delusion of demonic possession developed. The duration of untreated psychosis (the duration between the first appearance of the GDs and her first psychiatric treatment) lasted for about 3 years.

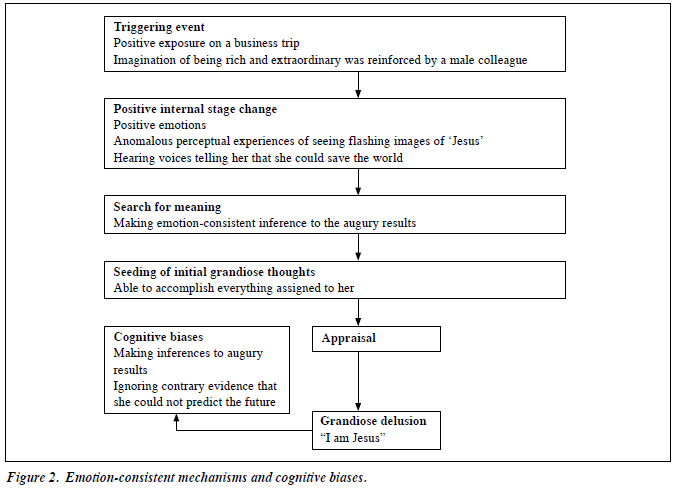

The figure of the preliminary model of GDs7 was adapted in the case conceptualisation of the formation of her GDs.

Therapy

The patient was diagnosed with schizophrenia. She was treated with risperidone 2 mg and referred to an early intervention case management service (Jockey Club Early Psychosis Project) which provided psychosocial intervention by a case manager. The case manager engaged the patient and her family with empathic feedback, thorough assessment, and case formulation. After taking medication for about 2 months, the patient reported that she felt less scared and no longer saw the black objects. The case manager investigated her illness beliefs that her experiences of being ‘Jesus’ and being possessed were real, but the patient started to doubt why the black objects were gone after she had started taking medication. The case manager helped the patient to explore the emotions generated from the anomalous experiences, and found out the relationship between these experiences and her previous life events. When the patient started to doubt whether her experience of being ‘Jesus’ was unreal, it was noticed that her self-esteem was fluctuating and she reported that she felt ashamed. The case manager gave empathic feedback and normalised the potential influences of cognitive biases and emotional state on a person’s inferences to the life experience with the Activating event–Beliefs-Consequences model.12

Assessment of delusion formation was done in the following areas: early experience, triggering events, and maintaining factors. The patient recalled that she was shy and was criticised as being craven when she was young. She had coped with the stress by indulging in her imagination of being a rich and extraordinary person since primary 5. She attributed the positive experiences to external factors such as luck. However, she tended to anticipate negative comments about her personality. This reasoning pattern of the externalising style of positive experiences and internalising style of negative comments lowered her self- esteem (Fig 1).

The patient recalled that she became very confident after the positive exposure of the business trip. She felt extremely good about herself. The positive experience triggered some positive emotional reactions and some anomalous perceptual experiences such as seeing flashing images of ‘Jesus’ and hearing voices. According to the emotion-consistent model, the interaction of these internal positive state changes and her habitual visual mental imagery of being extraordinary seeded the initial GDs (Fig 2).

Her GDs were maintained by cognitive biases, such as jumping to conclusions (making inferences for the augury results) and selective attention (ignoring the disproving evidence of being incapable of predicting the future through augury).

The case manager also clarified the patient’s core beliefs about herself by looking at her automatic thoughts in response to her previous life events. She reported that she had a strange idea of hurting small animals when she saw them. She also shared her experiences of having intrusive ideas about hurting others. She felt ashamed about these thoughts. The case manager introduced the nature of the intrusive thought and started exploring the emotions and meaning behind the thoughts. The process facilitated the patient in reflecting on her experiences of being disdained and the associated emotional reactions. She blamed and hated herself for being weak and unable to refute these experiences. She realised that her emotional reactions towards the small animals and other people originated from her underlying anger towards herself. With this understanding, her intrusive thoughts of hurting animals and her shamefulness about herself were reduced.

The case manager explained the delusion formation mechanism and its relationship to her past experiences and emotions. This helped her to make sense of her anomalous experiences and normalise her responses to stress. This understanding also facilitated her ability to identify possible ways to improve her handling of stress and criticism.

Some common cognitive biases were also explored and setbacks were discussed. The patient was aware of her unrealistic expectations which could induce tremendous stress. The skills of setting appropriate expectations and self-evaluation were introduced.

Discussion

Patients with schizophrenia need pharmacological treatment and require follow-up throughout the course of the illness. In conjunction with psychosocial intervention and thorough case formulation, patients could be further empowered to handle psychological stresses and reduce the level of self- stigma by making sense of the illness experiences in the context of their life experiences. Both positive and negative evidences are available for the DAD and emotion-consistent models. For this patient, it was observed that GDs induced positive emotions about herself. It is important to provide suitable psychosocial intervention in consideration of the potential negative psychological impact on a patient’s emotions and self-esteem when the GDs are being removed. It is of interest that the application of both the DAD and emotion-consistent models in case formulation and care plan development give a direction in case management service for patients with first-episode psychosis. This report has clear limitations in that it is a discussion of a single case and the case formulation is speculative at this time. Studies on the clinical outcome of the model’s application are needed.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. We thank our collaborating partners, the Hong Kong Hospital Authority, the Caritas Hong Kong (Social Work Services), and the Mental Health Association of Hong Kong.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. APA: Washington, DC; 2000.

- Ben-Zeev D, Morris S, Swendsen J, Granholm E. Predicting the occurrence, conviction, distress, and disruption of different delusional experiences in the daily life of people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2012;38:826-37.

- Meyer T, Krumm-Merabet C. Academic performance and expectations for the future of people putatively at risk for bipolar disorders. Personal Individ Differ 2003;35:785-96.

- Beck AT, Rector NA. Cognitive approaches to schizophrenia: theory and therapy. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1:577-606.

- Bentall RP. Cognitive biases and abnormal beliefs. Towards a model of persecutory delusions. In: David AS, Cutting JC, editors. The neuropsychology of schizophrenia. London: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994: 337-60.

- Freeman D, Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Bebbington PE. A cognitive model of persecutory delusions. Br J Clin Psychol 2002;41:331-47.

- Knowles R, McCarthy-Jones S, Rowse G. Grandiose delusions: a review and theoretical integration of cognitive and affective perspectives. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:684-96.

- Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Freeman D, Bebbington PE. A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychol Med 2001;31:189-95.

- Smith N, Freeman D, Kuipers E. Grandiose delusions: an experimental investigation of the delusion-as-defence hypothesis. J Nerv Ment Dis 2005;193:480-7.

- Freeman D, Garety PA. Connecting neurosis and psychosis: the direct influence of emotion on delusions and hallucinations. Behav Res Ther 2003;41:923-47.

- Smith B, Fowler DG, Freeman D, Bebbington P, Bashforth H, Garety P, et al. Emotion and psychosis: links between depression, self-esteem, negative schematic beliefs and delusions and hallucinations. Schizophr Res 2006;86:181-8.

- Kingdon D, Turkington D. The ABCs of cognitive-behavioral therapy for schizophrenia. Psychiatr Times 2006;23:49.