East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013;23:91-101

THEME PAPER

Dr S. Yusoff, MBBS, MMed (Psy), Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Sultan Ismail, Johor Bahru, Malaysia.

Dr C. T. Koh, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Sultan Ismail, Johor Bahru, Malaysia.

Dr M. Y. Mohd Aminuddin, MD, MPH, Health Technology Assessment, Ministry of Health Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia.

Ms M. Krishnasamy, BSc, Dip MLT, Medical Device Bureau, Ministry of Health Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia.

Dr M. Z. Suhaila, MB BCh BAO, MMed (Psy), Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Address for correspondence: Dr Suraya Yusoff, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Sultan Ismail, Jalan Mutiara Emas Utama, Taman Mount Austin 81100, Johor Bahru, Malaysia.

Tel: (606-7) 3565 121; Fax: (606-7) 3565 056; Email: surayay@hsi.gov.my

Submitted: 19 March 2013; Accepted: 21 May 2013

Abstract

Objective: The Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) for Management of Dementia (second edition) was launched in April 2010 by the Ministry of Health Malaysia. A training programme for the management of dementia, involving all categories of staff working at primary and secondary centres, was implemented to ensure that care delivery for people with dementia was in accordance with the guidelines. The study aimed to look into improving knowledge and understanding of dementia following training, and to evaluate the effectiveness of the training programme using a clinical audit indicator recommended in the guidelines.

Methods: The study entailed 2 phases (at national and state levels). The first phase involved the CPG training programme run as a 1.5-day workshop, in which participants filled up pre- and post-workshop questionnaires. A second phase involved analysing all the referral letters to the memory clinic at the Hospital Sultan Ismail, Johor Bahru 1 year before and after the training programme.

Results: There was a significant improvement in knowledge about dementia and its management among the health care professionals following training. The mean percentage score for the pre-workshop test was 63% while for the post-workshop test it was 78%, giving a difference of 15%. Although there was an overall improvement in knowledge gain following training in both specialist and non-specialist groups, these differences were not statistically significant (t = 1.32; 95% confidence interval, -2.61 to 9.61; p = 0.25). The proportion of referrals with a possible diagnosis of dementia from primary clinic referrals to the memory clinic also increased from 18% to 44% after training.

Conclusion: There was an overall improvement in the knowledge about dementia among the health care professionals following the training, which was reflected in the increase in referrals to the memory clinic. Although the initial results appeared to be promising, a multicentre study is warranted to conclude that the training had been effective.

Key words: Dementia; Health personnel; Malaysia; Practice guidelines as topic

摘要

目的:马来西亚卫生部於2010年4月发佈马来西亚脑退化临床服务指引第二版。本研究针对第一和第二层医疗服务医院的医护人员脑退化症治疗培训计划,确保他们能依照指引提供适切的脑退化症医护服务。本研究旨在初步评估培训计划後他们对脑退化症知识和了解的改善情况,以及使用指引建议的临床审核指标评估培训计划的效率。

方法:以国家级和州级分两阶段进行。第一阶段培训计划是为期1.5天的工作坊,参与者须於工作坊前後填写调查问卷。第二阶段则分析培训计划前後1年,於马来西亚鬚丹依斯迈医院记忆诊所收到的转介状况。

结果:完成培训计划後,医护专家对脑退化症的知识和治疗有明显改善,平均百分比比分由培训计划前的63%升至78%,增幅达15%。虽然经培训後,专科和非专科组在整体知识增益方面有所改善,但差异并无统计学意义(t = 1.32;95%置信区间,-2.61至9.61;p = 0.25)。培训计划後,由第一层医疗诊所转介到记忆诊所的疑似脑退化症患者转介比例由18%增至44%。

结论:培训计划後,脑退化症转介至记忆诊所的个案上升,反映医护专家对脑退化症的知识整体有所改善。虽然研究的初步结果看来是有为的,但仍须进行跨中心研究进一步确认培训计划的成效。

关键词:脑退化症、医疗专家、马来西亚、特定实践指引

Introduction

As in other developing countries, Malaysia is experiencing a rapid rise in the number of elderly persons in the population. Moreover, it is predicted that the proportion will continue to increase from the current 8% to 12% by the year 2030.1,2 Of concern is the prevalence of dementia in Malaysia. In 2005 the prevalence of dementia was estimated to be 0.063% with an annual incidence rate of 0.020%. Consequently, its prevalence is expected to increase to 0.126% in 2020 and 0.454% in 2050.3

Dementia has enormous health and financial consequences, not only for the affected individuals, but also specifically for their family caregivers as well as to society in general.4 There have been initiatives to improve dementia care service delivery at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels in Malaysia. The Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) for Management of Dementia developed by the Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOHM) were launched in 2010.5 The key priorities they identified were prevention and risks, coordination and integration of care, memory clinic services, assessment and diagnosis, structural imaging, intervention strategies, challenging behaviours, and care of the caregivers. These can be achieved through education and training of the target population.5 Hence, a quick reference for health care providers, patient information leaflets, and a teaching module was prepared at the same time. The guidelines also propose 2 clinical audit indicators, i.e. the number of people suspected with dementia referred from primary care to the memory / specialist clinics, as well as the percentage of antipsychotic drug use to control the behaviour and psychological symptoms of dementia.

The first step involved the training of the health care providers, for which training modules were specifically developed by the CPG developmental committee. The modules were made up of 3 parts: 10 didactic lectures, 6 case vignettes, and pre- and post-evaluation questionnaires. To be more effective, the modules were developed to be as interactive as possible. Both the hard copy and soft copy versions of the manual was made available to the participants.

The national-level training programme for the core trainers or ‘champions’ (a term defined by the MOHM as a group of leaders ensuring the continuation of the CPG training at their respective state level) was completed in September 2010, whereby 44 participants comprised psychiatrists, geriatricians, family medicine specialists, and hospital administrators who attended a 1.5-day workshop. A report by the Malaysian Health Technology Assessment Unit of the MOHM stated that all participants felt that this training had benefited them, and 97% said that they would recommend the training module to others.6

The ‘champions’ were expected to initiate the second phase of training for other health care providers at the state level. By 2011, about 935 health care providers had been trained nationwide, of which about a third (n = 282) were medical professionals.7 The second echelon of trainers was expected to train the health care providers in their respective districts and hospitals. As the training module was very comprehensive, allowance was given for the trainers to modify the module according to the category of the target population. The MOHM stipulated that echo training of the CPG should be made as one of the continuous programmes in hospitals and primary health care facilities in order to disseminate evidence-based recommendations made in the CPG.6

In the State of Johor, initial echo training was carried out in January 2011 and involved both primary and secondary care specialists. The state was carved into northern (comprising the districts of Muar, Tangkak Segamat), central (Kluang, Mersing, Batu Pahat), and the southern (Johor Bahru, Kulai, Pontian, Kota Tinggi) zones. A leader was identified for each zone and was tasked to carry out further training and ensure that a large number of health care providers were trained.

For the southern zone, its leader opted to split the training into 2 different target groups. The first comprised health care professionals (doctors and pharmacists) who received the full comprehensive package (1.5-day workshop). The second group were allied health care staff (physician assistants, nurses, rehabilitation officers, and administrative staff) whose programme was shortened to a 1-day workshop. This study focuses on the training in the southern zone and is confined to the first group (health care professionals), as the simplified training for the second group was still under development. The study was registered with the National Medical Research Register (Research ID: 12365).

The study aimed to explore any improvements in knowledge and understanding of dementia following training of the health care professionals based on the Malaysian CPG. Knowledge gained by specialists and non- specialists was evaluated together with the effectiveness of the training sessions, based on any increase in the number of referrals to the memory clinic (a recommended clinical audit indicator).

Methods

The first part of the study involved the training programme that was initially conducted at the Hospital Sultan Ismail, Johor Bahru (HSIJB) in separate months (February and April 2011). The duration of each workshop was about 14 hours, and entailed lectures and case discussions. In all, 72 participants (22 specialists, 38 medical officers, and 12 pharmacists) attended the workshop. The pharmacists were included as they were involved in the purchase of anti-dementia drugs at the public hospitals and health centres. All participants were given a questionnaire based on the contents of the CPG for the Management of Dementia (second edition) completed before and after the training programme. A total of 59 (82%) of the participants completed both sets of questionnaires. Of the remaining 13 participants, 7 did not fully complete both the pre- and post-evaluation forms, 5 did not return the pre-evaluation forms, and 1 did not return the post-evaluation form. Their responses were therefore excluded from the final analysis. All subjects were reassured that the tests were done in anonymity and only identified according to their occupation. The questionnaire covered 9 modules which were further divided into 20 topics. Each respondent was asked a total of 91 questions with either true / false answers, and given 30 minutes to complete the questionnaire. The maximum score of each module was shown in Table 1. Each correct answer was scored 1 or incorrect answer was scored 0. The mean score of each module was obtained on summing up all scores over the number of participants. The mean score was then divided by the maximum score to obtain the percentage score of that module.

Although other psychiatric departments of the other 2 major hospitals in Johor Bahru accept referrals, the majority of suspected dementia patients were eventually diverted to the HSI memory clinic. The second part of the study involved scrutinising all referral letters for patients with suspected dementia sent to the HSI memory clinic. These referral letters requesting appointments in the year before and after the training programme were collected and checked for the following key words: ‘dementia’, ‘Alzheimer’s disease’ (AD), ‘senile dementia’, ‘cognitive impairment / decline’, and ‘cognitive assessment’. The cutoff date for deciding the periods before and after training was taken to be 1 month after the last workshop. The referral letters were divided into 2 categories: those from the public primary care clinics and those from the private general practitioners. Only the letters from the former were analysed as the initial training programme was mainly directed at health care providers working in the public sector. It was expected to have an increase in the number of referrals to the secondary care hospitals and the HSI memory clinic.

Statistical Analysis

Data were recorded and analysed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Windows version 16. The means and standard deviations (SDs) of the pre- and post-training scores were calculated. Proportion of correct answers in each topic was measured to obtain the difficulty index (P).8 To indicate the extent to which the scale items discriminate between individuals with high or low scores, a discrimination index (DI) was also calculated. This involved estimating the number of correctly answered items among the high scorers (top 27%), subtracted from the low scorers (bottom 27%) then divided by the number of respondents comprising 27% of the sample.9

For the evaluation of the CPG training programme, the difference between the pre- and post-training results were evaluated using paired t tests. The significance level was taken as p < 0.05. The test questions were then merged according to 9 main training modules (Table 1) and the differences in the scores for each topic were analysed. An independent t test was performed to evaluate improvements among specialists and non-specialists. In the second part, the percentage increase in the number of referrals before and after the training of health care professionals were analysed and compared. Only the results of the medical group (doctors and pharmacists) and those that returned both sets of questionnaire were analysed.

Results

The mean (± SD) age of the participants attending the training programme was 37 ± 8 (95% confidence interval [CI], 35-39; range 26-49) years, and their mean duration of service was 12 ± 7 (95% CI, 10-14; range, 2-23) years. The number of participants from the hospital was comparable to those from primary health centres (PHC) [47% vs. 51%]. Among the specialists (n = 21), 8 (38%) were psychiatrists, 12 (57%) were family medicine specialists, and 1 (5%) was a physician. Among the medical officers (n = 32), 9 (28%) were from psychiatry, 16 (50%) from the PHC, and 7 (22%) from other disciplines. The number of pharmacists (n = 6) from the hospital and PHC were similar. Majority of the participants were female (73%). Evaluation scores of pharmacists were lumped together with the medical officers (as the group of non-specialists) for analysis.

The P and DI are shown in Table 2. The highest P was on capacity (0.84), whilst the lowest was on cognitive enhancers (0.4). The higher the P, the lower the difficulty of an item. The DI (0.43-0.72) for the topics in this study appeared to fall within the ideal range of 0.3-0.7.8,9 Difficulty index is usually used in concert with the DI, in which a high DI suggests that each item differentiates adequately between participants on their knowledge of dementia.

There was an overall significant improvement in knowledge about dementia and its management among health care professionals following the training. The mean pre-workshop score was 57.27 ± 9.79 (range, 32-82), while for the post-workshop score it was 70.97 ± 0.78 (range, 55-88), i.e. an increase of 13.70 ± 87 (95% CI, -48 to -2; p = 0.03). The corresponding mean percentage score pre- workshop was 63%, while for the post-workshop it was 78%, giving an overall improvement of 15%.

Before the training session, 27% of participants scored < 60, but only 2% after the training. The lowest percentage score was 32% before training, and improved to 70% after the training session. There was no correlation between the duration of service and knowledge about dementia before training (Pearson r = 0.16; p = 0.22) or after training (Pearson r = 0.22; p = 0.10).

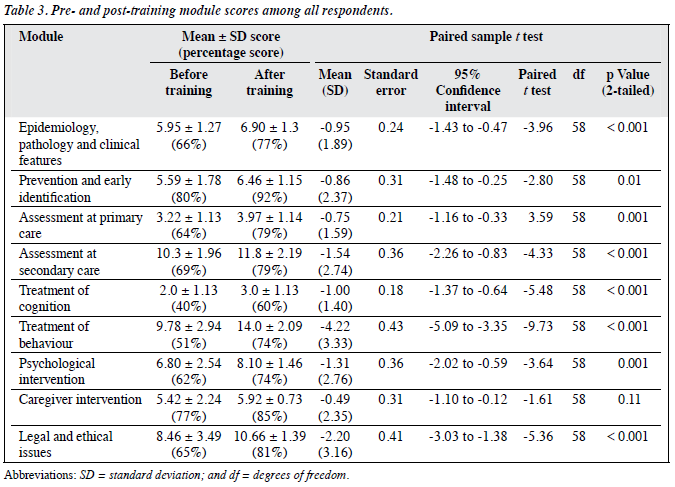

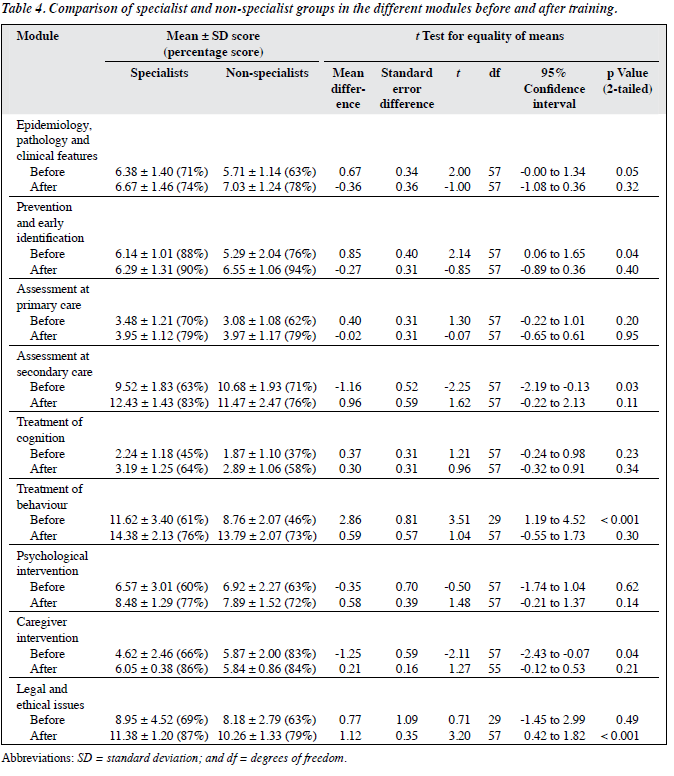

As indicated in Table 3, the prevention and early identification module showed the highest score before training (80%) and the lowest score was for treatment of cognition (40%). Overall, there was statistically significant improvement post-training in all the modules taught, with the exception for the module on caregiver intervention.

The results for specialists and non-specialists before and after training in different modules are shown in Table 4. Both groups showed an overall improvement in knowledge gain after training (mean scores: 59.52 to 72.81 in specialist group, and 56.03 to 69.95 in non-specialist group); however the differences were not statistically significant (t = 1.32; 95% CI, -2.61 to 9.61; p = 0.25). The differences in the knowledge gap between the groups were also not statistically significant (t = 1.80; 95% CI, -3.22 to 6.05; p = 0.08). Both the specialists and non-specialists showed improvement in the modules on epidemiology, prevention and early identification, assessment at secondary care, treatment of behaviour, and caregiver intervention. Although the pre-training scores on the module of legal and ethical issues are comparable in both groups, a statistically significant improvement was seen in the specialist group following training compared with the non-specialist group (mean scores: 11.38 vs. 10.26; p < 0.001) [Table 4].

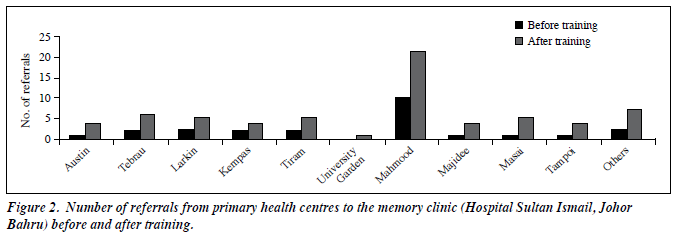

There were a total of 130 referrals for the year before the training programme and 149 referrals in the year after. There was a small improvement of 13% in the total number of referrals to the memory clinic. Before the training programme, a majority of referrals to the memory clinic were from the private general practitioners (71%), but the figure decreased to 37% after the training programme. On the other hand, there was a marked increase in the percentage of referrals from public health care facilities (including public hospitals and public PHC) from 29% to 63%, which amounted to an increment of 34%. Referrals from public health clinics to the HSIJB memory clinic amounted to 18% before training and 44% thereafter (Fig 1). There was an increase in the absolute number of referrals but this was not reflected in the percentage differences. The referrals from individual PHC did not increase significantly (Fig 2).

Discussion

In general, the level of knowledge of dementia among medical professionals (63%) prior to the training programme was satisfactory. This was similar to a postal survey in the United Kingdom, in which the general practitioners correctly answered 67% of the questions on knowledge on dementia.10 An overall improvement by 15% in the levels of knowledge after training was much lower than that obtained in 2 other studies, one among clinical psychologists and the other in a diverse group of health care staff.11,12 However, comparison of our results with other studies is difficult as the questionnaires used in the evaluation exercise were unique and ours was very much tailored to the Malaysian CPG for the management of dementia. The studies mentioned above used the 30-item Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS),13 which contains 30 true / false items to assess knowledge about AD and covers issues ranging from risk factors, assessment and diagnosis, symptoms, course, life impact, caregiving, as well as treatment and management. The same items are also within the modules of the evaluation questionnaire we had developed, which pertained to the curriculum of our training module. However, the ADKS contains representative items which indicate only a general knowledge view about AD, unlike our evaluation questionnaire which was more evidence-based and hence more specific to our training programme. On the other hand, the ADKS had been tested against a highly varied pool of respondents, ranging from the general public to medical practitioners.13

There is a lack of studies assessing improvements of knowledge following training or education on dementia among the medical professionals per se. Most studies looked into improvements in attitude towards dementia and behaviour of health care workers in general.14,15 The Clinician Partners Program16 to improve physician awareness of dementia provided a 3-day course of didactic, observational skill–based teaching techniques. Evaluation about the knowledge on dementia pre- and post-training was completed by 146 health care professionals taking part in the event. A 12-item scale to assess knowledge of health care professionals on University of Alabama-Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Test for Health Professionals was used. There was a significant improvement in knowledge about dementia 3 months after training. The improvement in knowledge was sustained even after 12 months.16

Multiple-choice questions were used in our evaluation of the training programme for several reasons. It was a simple method to assess knowledge in the short time available and covered a wider array of domains.8 The P and DI can help towards determining the effectiveness of the evaluation questionnaires. The DI of most of the questions (0.43-0.72) fell within the ideal reference level (0.3-0.7),8,9 as in this case it was used on a group of professionals with a high level of knowledge. The most difficult item with the lowest P (cognitive enhancers, 0.4) showed a fairly good DI of 0.54, which indicated that the performance of the participants was of the same level; even for easy questions (early identification [0.8], treatment of cognition [0.81], and caregiver assessment [0.82]) showed good DIs. The next step was to analyse our evaluation questionnaire on the other categories of health care workers that had gone through the same training programme.

The post-training evaluation found an overall statistically significant improvement in the knowledge of dementia and its management among the medical professionals. When assessed according to each of the 9 different modules, most participants showed better understanding of dementia in all the modules following the training programme. There were significant improvements in knowledge post-training in all modules except for the module of caregiver intervention (p = 0.11). The 2 modules showing highest percentage scores before training (80% on prevention and early identification and 77% on caregiver intervention) also showed highest scores in the post- evaluation results (92% and 85%), despite a small increase by 12% and 8%, respectively. The greatest improvement was in the module of treatment of behaviour (22%) followed by treatment of cognition (20%) as well as legal and ethical issues (16%). The lowest change seen was on caregiver (8%) and psychological interventions (12%).

Was there a difference in the gain of knowledge between the specialists and non-specialists? Before the training programme, the specialist group were significantly more knowledgeable than the non-specialists in the modules of epidemiology, prevention and early identification, as well as the treatment of behaviour, whereas the non-specialist group scored higher in the modules of assessment at secondary care and caregiver intervention.

After training, the 2 groups were able to close the knowledge gap. The greatest gain following training in the specialist group were seen in the modules of caregiver intervention (20%), assessment at secondary care (20%), management of cognition (19%), and legal and ethical issues (18%). Whereas in the non-specialist group, the knowledge gain was seen in the modules of management of behaviour (27%), treatment of cognition (21%), prevention (18%), and assessment at primary care (17%).

No statistical difference in the module of legal and ethical issues was found between the groups before training, but the specialist group showed greater improvement (+ 18%) than the non-specialists (+ 16%) after training (p < 0.001). This can be attributed to better exposure to these topics during postgraduate training, as well as better opportunities and exposures in this field for the specialist group as opposed to the non-specialist group.

Surprisingly, knowledge on treatment of cognition (anti-dementia therapy) before the training was low in both specialist (45%) and non-specialist (37%) groups. This may be because the use of anti-dementia medications among doctors in the public health services is mostly restricted to a small number of specialists (psychiatrists and neurologists). There might also be ambivalence about the current treatments available for the disorder due to a degree of fatalism associated with dementia among medical professionals.17,18 In the Facing Dementia Survey in several European countries, 87% of the physicians were cognisant of the fact that medication exists and there is a need for early treatment.19,20 The specialist group fared much better in handling treatment of behaviour before the training programme compared with the non-specialists. Following training in this module, the non-specialist group showed more improvement (+ 27%) than specialists (+ 15%), though neither attained statistical significance. The reasons for the improvement may be because the teaching and practice of medicine is very much based on the biological model, and hence is more acceptable to the medical professionals. Secondly, strong and convincing evidence supporting management of dementia was presented in the Malaysian CPG for dementia and had a major impact on medical professionals. This may also explain why there is only modest change evident in the module of psychological intervention, for which the evidence presented was much weaker. In both groups, the module for prevention and risk factors showed a high score even before training. This was probably due to emphasis being placed on promotional activities such as prevention of morbidities and healthy lifestyle campaigns at the national level. A significant number of participants were based at primary care centres. Although non-specialists obtained higher percentage score (94% vs. 90% in specialists) in this module post-training, the difference was not statistically significant. The only module which showed statistically significant difference between the specialist and non-specialist groups was on legal and ethical issues. This is reflected in the current practice whereby medico-legal issues and palliative care are often handled by the specialists, rather than the juniors or primary care doctors. It is a difficult topic for the junior doctors to grasp as there is limited exposure to these issues in the medical school curriculum. The time allotted to this subject may not be sufficient to improve the understanding. The specialists showed the least improvement in the modules of prevention (+ 2%) and epidemiology (+ 3%) post-training, which may reflect the level of exposure to the theoretical aspects of dementia during their years of training. For the non-specialists, they attained least improvement in the caregiver intervention (+ 1%). Interestingly, the pre-training scores for the non-specialists were better (83% vs. 66%). This may be explained by the fact that the junior officers dealt more with the caregiver as opposed to the specialists.

Education and training of target groups is one strategy recommended to ensure adherence. Adherence to most clinical guidelines among physicians has always been poor.21-23 Skepticism and barriers to adherence to clinical guidelines in general are widespread.24-26 Gifford et al27 found that there was at least 95% agreement on 3 out of 6 specialty society-endorsed practice recommendations in a group of neurologists given an educational strategy on dementia, compared with neurologist not provided such education. Many studies have looked into adherence to dementia guidelines following various categories of training directed at target groups.28,29 It is a fact that dementia is under- recognised, under-diagnosed, and under-treated.30 This is also true in Malaysia, where among various general mental health problems, dementia is often missed by frontline doctors in primary health clinics.31,32 The need for clinical guidelines and education are more obvious for primary care physicians than secondary level carers. However, levels of perceived self-competence are also important, as some have found that medical professionals who perceived low self- competence expressed a greater interest in guidelines.10,33,34 Thus, doctors working in the primary health clinics are an important target group for training. This is also in line with the common core recommendation in most guidelines. Despite variations in care systems, it is of utmost importance to recognise early signs and symptoms of dementia and follow thorough multi-dimensional evaluation at the primary care level.5,35-38

The Malaysian CPG for dementia favours referral to a specialist consultant as the next level of care following diagnosis.5 If an early detection programme involving the primary care practitioners is to be recommended, then it needs to be coupled with specialist services.39,40 It is therefore appropriate that one of the audit indicators suggested was the percentage of referrals from the primary care clinics to memory or other specialist clinics.5 Although the overall increment in the number of referrals was small (15%), there was a definite increment of referrals (34%) for those with suspected dementia from the public health care facilities in the year after the CPG training programme compared with the previous year. The increase in referrals from the PHC was almost treble (differential increment of 26% overall), whilst referrals from the hospitals was double (differential overall increment of 8%). However, whether this was a direct result of the training programme itself cannot be confirmed. Alternatively, the majority of referrals were merely being routed to the HSIJB instead of other public secondary level care hospitals in Johor Bahru. When the referrals were traced according to each individual PHC, there was an increase in terms of the absolute numbers but the percentage increment was small. In spite of an increase in absolute numbers of referrals in 4 centres (Larkin, Tiram, Mahmoodiah, and Kempas), there appeared to be an overall percentage decrement of referrals.

Dementia screening remains controversial, despite evidence showing that it improves case findings.41-43 Borson et al44 showed that Mini-Cog screening by office staff was feasible and had an impact on primary care doctors. The inclusion of the public health division of the MOHM on the CPG dementia committee leads to the development of a simplified manual for use by the primary health clinic staff.45 It will be interesting to evaluate the results of dementia screening at primary care clinics if such a programme is implemented. This is because the results of screening tests performed by primary care doctors were not mentioned in the referral letters we reviewed.

Education and training has to be a continuous process if management of dementia is to improve. The Dementia Education Strategy,46 a 3-year project developed by the University of British Columbia, highlighted the effectiveness of education in promoting physician behaviour change and practice in the management of dementia. The report also suggested that evaluations must be conducted in an ongoing and comprehensive manner.46 We are unsure of how much impact we had on our participants in the long term as there were no follow-up assessments, which are more time-consuming, resource-intensive, and logistically more difficult to conduct.47 Outcomes from training should be more than just a gain of knowledge. It should also achieve improved skills and changes in attitudes towards patient management.48 Rodriguez et al48 felt that ‘action plans’ appeared to stimulate behavioural changes in clinicians working with patients with dementia and their families, and at the same time identify barriers to change as well as ways to overcome such barriers. This interesting suggestion is not impossible to incorporate as one of the outcome measures in future training programmes.

Strengths, Limitations, and Recommendation

The strength of this study was that the format of the teaching was standardised and the materials provided were uniformed. Training was offered in a workshop format with small group discussions of the case vignettes. Participants were each given copies of the guidelines, slides of the lectures, and case vignettes on a CD-ROM. Practice-based workshops continue to offer robust and effective educational approaches to improve detection rates of dementia.49 We used improvement of knowledge and increase in the number of referrals as indication of early detection, as a measure of outcomes of our training programme. The main weaknesses of our study were its retrospective nature and the small number of subjects. We were only able to analyse 38% (108/284) of the medical professionals that had undergone dementia training in the State of Johor (or 12% [108/935] nationwide). Due to inconsistencies and incomplete data collection from other centres and the lack of a central data collection, it was decided to limit the analysis of the training to the HSIJB only. Another weakness was in the quality of referral letters, which lacked details on the history and physical examination. A scrutiny of the medical records may be a better option as these might highlight whether the primary care clinic practitioners were in concordance with the algorithm outlined in the guidelines. Most of the cognitive assessments at the PHC were carried out by primary care nurses, and potential cases were then referred for further assessment to available doctors on duty. Thus, it was possible that referred patients were primarily from nurse who had attended the CPG workshop. Hence, we could only limit analysis of referrals according to the different health centres rather than specific individual doctors.

The initial findings revealed a few shortcomings in the evaluation process, which warranted improvements, including feedback from participants and facilitators, with different needs.50 A third component to any training programme is a follow-up survey 3 to 6 months later.49 The training of medical professionals needs to be sustained and done on a continuing basis. Training of other categories of staff is ongoing, and it will be interesting to analyse their pre- and post-training test scores. It is also important to check on the effectiveness of the programme by continuous audit cycles, but this require a sustained commitment and effort from all concerned. Training of health care staff is just a small step in the right direction. Dementia is a complex issue as it involves multiple agencies and members of the community, for which training is needed at every level of the community. This is almost impossible to achieve unless the country develops a national dementia strategy to coordinate and ensure the smooth running of programmes. In the meantime, we need to re-update our methods of evaluation for the training programme and involve more centres to collaborate in collating findings.

Conclusion

Overall, there was an improvement in the knowledge of dementia among the health care professionals following the training, which was reflected in the increase in the number of referrals to the HSI memory clinic. Although the initial results at one centre appeared to be positive, it is too early to conclude that the training was a success. A larger prospective study with multicentre involvement is needed to arrive at a definitive conclusion that such training is effective in improving dementia care in the country.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Director of Health Malaysia for permission to publish this paper.

References

- Population Division, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, United Nations. Population Ageing and Development; 2012.

- Karim HA. The elderly in Malaysia: demographic trends. Med J Malaysia 1997;52:206-12.

- Dementia in the Asia-Pacific Region: the epidemic is here. Melbourne: Access Economics for Asia Pacific Members of Alzheimer’s Disease International; 21 September 2006.

- Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, Pearson ML, Della Penna RD, Ganiats TG, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:713-26.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Dementia. 2nd ed. Malaysian Health Technology Assessment, Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2009.

- Report on the training of core trainers workshop on Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Dementia. 2nd ed. 28-29 September, Malaysian Health Technology Assessment, Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2011.

- The CPG Unit, Health Technology Assessment Section, Medical Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia. Report on Echo Training of Clinical Practice Guidelines Training Modules; 2011.

- Sim SM, Rasiah RI. Relationship between item difficulty and discrimination indices in true / false-type multiple choice questions of a para-clinical multidisciplinary paper. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2006;35:67-71.

- Kelley TL. Selection of upper and lower groups for the validation of test items. J Educ Psychol 1939;30:17-30.

- Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, Wilcock J, Bryans M, Levin E, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing 2004;33:461-7.

- Nordhus IH, Sivertsen B, Pallesen S. Knowledge about Alzheimer’s disease among Norwegian psychologists: the Alzheimer’s disease knowledge scale. Aging Ment Health 2012;16:521-8.

- Smyth W, Fielding E, Beattie E, Gardner A, Moyle W, Franklin S, et al. A survey-based study of knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease among health care staff. BMC Geriatrics 2013;13:2.

- Carpenter BD, Balsis S, Otilingam PG, Hanson PK, Gatz M. The Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale: development and psychometric properties. Gerontologist 2009;49:236-47.

- Sullivan K, Muscat T, Mulgrew K. Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease amongst patients, carers, and non-carer adults: misconceptions, knowledge gaps, and correct beliefs. Top Geriatr Rehabil 2007;23:148- 59.

- Foreman P, Gardner I. Evaluation of education and training of staff in dementia care and management in acute settings. Melbourne, Victoria: Aged Care Branch; 2005.

- Galvin JE, Meuser TM, Morris JC. Improving physician awareness of Alzheimer disease and enhancing recruitment: the Clinician Partners Program. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2012;26:61-7.

- Hinton L, Franz CE, Reddy G, Flores Y, Kravitz RL, Barker JC. Practice constraints, behavioral problems, and dementia care: primary care physicians’ perspectives. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1487-92.

- Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, Delepeleire J. What is the role of the general practitioner towards the family caregiver of a community- dwelling demented relative? A systematic literature review. Scand J Prim Health Care 2009;27:31-40.

- Bond J, Stave C, Sganga A, O’Connell B, Stanley RL. Inequalities in dementia care across Europe: key findings of the Facing Dementia Survey. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2005;(146):8-14.

- Wilkinson D, Sganga A, Stave C, O’Connell B. Implications of the Facing Dementia Survey for health care professionals across Europe. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2005;(146):27-31.

- McKinlay JB, Link CL, Freund KM, Marceau LD, O’Donnell AB, Lutfey KL. Sources of variation in physician adherence with clinical guidelines: results from a factorial experiment. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:289-96.

- Lugtenberg M, Zegers-van Schaick JM, Westert GP, Burgers JS. Why don’t physicians adhere to guideline recommendations in practice? An analysis of barriers among Dutch general practitioners. Implement Sci 2009;4:54.

- McDonnell Norms Group. Enhancing the use of clinical guidelines: a social norms perspective. J Am Coll Surg 2006;202:826-36.

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458-65.

- Mangin D. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines is the key to improved health outcomes for general practice patients: NO. J Prim Health Care 2012;4:158-60.

- Pimlott NJ, Persaud M, Drummond N, Cohen CA, Silvius JL, Seigel K, et al. Family physicians and dementia in Canada: Part 1. Clinical practice guidelines: awareness, attitudes, and opinions. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:506-7.e1-5.

- Gifford DR, Holloway RG, Frankel MR, Albright CL, Meyerson R, Griggs RC, et al. Improving adherence to dementia guidelines through education and opinion leaders. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:237-46.

- Cherry DL, Vickrey BG, Schwankovsky L, Heck E, Plauchm M, Yep R. Interventions to improve quality of care: the Kaiser Permanente- alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Project. Am J Manag Care 2004;10:553-60.

- Galvin JE, Sadowsky CH; NINCDS-ADRDA. Practical guidelines for the recognition and diagnosis of dementia. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:367-82.

- Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:306-14.

- Mimi O, Tong SF, Nordin S, Teng CL, Khoo EM, Abdul-Rahman A, et al. A comparison of morbidity patterns in public and private primary care clinics in Malaysia. Malaysian Family Physician 2011;6:19-25.

- Institute for Public Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia. The Third National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS III) 2006. Vol 1; 2008.

- Kaduszkiewicz H, Wiese B, van den Bussche H. Self-reported competence, attitude and approach of physicians towards patients with dementia in ambulatory care: results of a postal survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:54.

- Aminzadeh F, Molnar FJ, Dalziel WB, Ayotte D. A review of barriers and enablers to diagnosis and management of persons with dementia in primary care. Can Geriatr J 2012;15:85-94.

- Feldman HH, Jacova C, Robillard A, Garcia A, Chow T, Borrie M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 2. Diagnosis. CMAJ 2008;178:825-36.

- Hogan DB, Bailey P, Black S, Carswell A, Chertkow H, Clarke B, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 4. Approach to management of mild to moderate dementia. CMAJ 2008;179:787-93.

- Villars H, Oustric S, Andrieu S, Baeyens JP, Bernabei R, Brodaty H, et al. The primary care physician and Alzheimer’s disease: an international position paper. J Nutr Health Aging 2010;14:110-20.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 42. London, UK: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2007.

- Woods RT, Moniz-Cook E, Iliffe S, Campion P, Vernooij-Dassen M, Zanetti O, et al. Dementia: issues in early recognition and intervention in primary care. J R Soc Med 2003;96:320-4.

- Yaffe MJ, Orzeck P, Barylak L. Family physicians’ perspectives on care of dementia patients and family caregivers. Can Fam Physician 2008;54:1008-15.

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, Tu SP, Lessig M. Improving identification of cognitive impairment in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21:349-55.

- Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG, Perkins AJ, Fultz BA, et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:572-7.

- Harvan JR, Cotter V. An evaluation of dementia screening in the primary care setting. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2006;18:351-60.

- Borson S, Scanlan J, Hummel J, Gibbs K, Lessig M, Zuhr E. Implementing routine cognitive screening of older adults in primary care: process and impact on physician behavior. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:811-7.

- Manual Pengendalian kes demensia di peringkat penjagaan primer [in Malay]. Bahagian Pembangunan Kesihatan Keluarga, Jabatan Kesihatan Awam, Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia; 2009.

- Brennan L, Maultsaid D, Bluman B. Final Report Dementia Education Strategy 2007-2010. The University of British Columbia, Faculty of Medicine, Division of Continuing Professional Development; 2010.

- Ratanawongsa N, Thomas PA, Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Wilson LM, Ashar BH, et al. The reported validity and reliability of methods for evaluating continuing medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med 2008;83:274-83.

- Rodriguez E, Marquett R, Hinton L, McBride M, Gallagher-Thompson D. The impact of education on care practices: an exploratory study of the influence of “action plans” on the behavior of health professionals. Int Psychogeriatr 2010;22:897-908.

- Downs M, Turner S, Bryans M, Wilcock J, Keady J, Levin E, et al. Effectiveness of educational interventions in improving detection and management of dementia in primary care: cluster randomised controlled study. BMJ 2006;332:692-6.

- Iliffe S, Eden A, Downs M, Rae C. The diagnosis and management of dementia in primary care: development, implementation and evaluation of a national training programme. Aging Mental Health 1999;3:129-35.

- Cameron MJ, Horst M, Lawhorne LW, Lichtenberg PA. Evaluation of academic detailing for primary care physician dementia education. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2010;25:333-9.