East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013;23:126-32

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Cindy Woon-Chi Tam, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Prof. Linda Chiu-Wa Lam, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), MD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Cindy Woon-Chi Tam, Department of Psychiatry, G/F, North District Hospital, 9 Po Kin Road, Sheung Shui, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 2683 7620; Fax: (852) 2683 7616; email: tamwoonchi@hotmail.com

Submitted: 21 May 2013; Accepted: 12 July 2013

Abstract

Objective: Better understanding of the relationship between executive and memory functions and treatment response in late-onset depression may improve our ability to identify those individuals who are less likely to benefit from traditional pharmacological interventions. This study aimed to investigate the remission rate in elderly Chinese people with late-onset depression, and to examine the predictors of outcomes.

Methods: Patients aged 60 years or older with late-onset depression without dementia were recruited into the study. Mood symptoms were assessed by the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression and Neuropsychiatric Inventory at 12 and 24 weeks. Cognitive domains assessed included global cognitive function, episodic memory, executive functions, and processing speed. The clinical characteristics and cognitive scores were compared among the early remitters, late remitters, and non-remitters.

Results: Of the 105 subjects, 42 (40%) had remission at 12 weeks and were categorised as early remitters, 41 (39%) who did not remit at 12 weeks achieved remission at 24 weeks (late remitters), and 22 (21%) had not achieved remission at 24 weeks (non-remitters). Executive function, processing speed, episodic memory, apathy and depression severity were related to remission outcomes. Regression analyses found that severity of baseline apathy and depression were predictors of remission at 12 and 24 weeks, respectively.

Conclusions: This study identified 2 subgroups of patients according to outcomes. One group with clinical characteristics similar to vascular depression achieved a late response to treatment. The other group were non-remitters who had features of depression–executive dysfunction syndrome, which might have underlying degenerative process and presented with the co-occurrence of depression and mild cognitive impairment.

Key words: Depressive disorder; Executive function; Remission induction

摘要

目的:对执行及记忆功能与治疗成效之间的关系的更多理解,或有助辨识较不可能受益于传统药物干预的晚发抑郁患者。这项研究旨检视晚发抑郁华籍老年患者的症状缓解情况以及治疗成效的预报因子。

方法:研究对象为60岁或以上晚发抑郁但没有脑退化症的华籍老年患者,以汉密尔顿抑郁评定量表和神经精神量表评估他们于第12和24周的心情症状。认知领域评估包括总体认知功能、情节记忆、执行功能和加工速度。研究并根据患者的缓解成效分为三组,并比较他们的临床特征和认知比分。

结果:105名患者中,42名(40%)能于第12周得到症状缓解(早期缓解组),41名(39%)于第24周才得到症状缓解(晚期缓解组),余下22名(21%)则未能达到症状缓解(未能缓解组)。执行功能、加工速度、情节记忆、情感淡漠和抑郁重度皆与缓解成效相关。回归分析显示基线情感淡漠和抑郁比分分别为第12周和第24周症状缓解的预报因子。

结论:这项研究可根据患者的治疗成效再细分为两组。其中一组的临床特征与血管性抑郁相若,导致治疗成效有所延缓。另一小组(未能缓解组)则因根本的退化问题导致抑郁及执行功能障碍综合征以至同时出现抑郁和轻度认知障碍。

关键词:抑郁症、执行功能、缓解诱导

Introduction

Late-onset depression is a heterogeneous syndrome that includes patients with a high medical burden and neurologic disorders that may or may not be clinically evident when the depression first appears. A review of elderly community and primary care populations, in which most subjects were untreated, found that at 24 months, 33% of subjects were well, 33% were depressed, and 21% had died.1 Hybels et al2 reported that at 3 months, 37.6% of treated patients had remitted. Flint and Rifat3 found that 83.2% of 101 outpatients achieved remission within 6 months of sequential treatment. Kok et al4 found an overall remission rate of 84% within 3 years and that greater severity and longer duration of the depressive episode at baseline predicted poor recovery. One treatment challenge is that approximately one-third of older adults are resistant to typical pharmacological intervention.5

Executive dysfunction has been reported to predict poor or delayed antidepressant response in elderly patients with major depression. Deficits in executive function, which broadly refers to a number of prefrontally mediated cognitive processes such as selective attention, response inhibition, planning, and performance monitoring, are associated with worse short- and long-term treatment responses and greater functional disability in patients with depression.6-8 The confluence of findings implicating a dysfunction of the frontal pathways in elderly people with depression has led to the depression-executive dysfunction (DED) syndrome hypothesis.7 This hypothesis postulates that in a subgroup of elderly patients with depression, frontostriatal dysfunction caused by cerebrovascular disease or other ageing conditions is the main predisposing factor to depression. It has been further hypothesised that DED syndrome has a distinct clinical presentation and poor long- and short-term outcomes.

Neuropsychological performance may be a sensitive indicator of neurobiological dysfunction and potential barriers to treatment response, which may be complementary to structural findings. A better understanding of the relationship between executive and memory functions and treatment response in late-onset depression may improve our ability to identify those individuals who are less likely to benefit from traditional pharmacological interventions. This study aimed to investigate the remission rates at 12 and 24 weeks in a group of elderly Chinese people with late-onset depression, and examine the predictors of remission with short-term treatment. We also examined whether the hypothesis of DED syndrome applies to the elderly Chinese people.

Methods

Subjects

Patients aged 60 years or older who fulfilled the DSM- IV-TR9 criteria for major or minor depression were recruited from the psychiatric outpatient clinics in the New Territories East Cluster and inpatient psychiatric unit at the North District Hospital, Hong Kong, from January 2007 to December 2009. The age of onset of the first depressive episode was 50 years or older. Each patient with depression was evaluated by a qualified psychiatrist to establish eligibility for inclusion in the study, a clinical diagnosis, and assessment of clinical staging using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale.10 Patients with a global CDR scale score of 0 or 0.5 were recruited.

Exclusion criteria were a history of: (a) other psychiatric disorders before the onset of the depressive disorder; (b) degenerative neurological disorder, dementia, cortical strokes, severe or unstable physical illness; and (c) current substance / alcohol abuse. Patients who had undergone electroconvulsive therapy in the previous 3 months were also excluded.

The psychiatrists explained the procedures and obtained informed consent from the subjects or their caregivers prior to the study. The study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong and New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Assessment Procedures

Cognitive Assessment

Global cognitive assessment was done using the Cantonese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)11 and the Chinese version of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog).12 To test for episodic memory, 10-minute delayed recall of a word list from the ADAS-Cog was used. The Visual and Digit Span (VADS) test was done to test attention and working memory. The Category Verbal Fluency Test (CVFT) and Similarities and Differences Test were performed to examine executive function. In the CVFT, subjects were asked to generate exemplars in the categories of animals, fruit, and vegetables within 1 minute. Combined scores were then computed.13 The Trail Making Test (TMT)14 Part A (TMT-A) was used to evaluate psychomotor speed and Part B (TMT-B) to evaluate executive function. The TMT-A assesses sustained attention, sequencing, and information processing / motor speed, while TMT-B additionally measures mental set shifting and response inhibition. We modified the TMT by changing the sequence of the alphabet to Chinese numbers in an ascending order as most subjects had not received education in the English language.

Functional Assessment

The Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD) scale is a validated measure of activities of daily living designed specifically for use in patients with dementia. The Chinese version of the DAD scale has been validated in Chinese patients.15

Severity of depressive mood was measured by the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD).16 Neuropsychiatric symptoms were assessed using the Chinese version of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) to define the presence and severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms.17,18

Medical illness burden was assessed by Cumulative Illness Rating Scale.19 Vascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, arrhythmia, heart disease, and cerebrovascular accident / transient ischaemic attack were recorded. The number of risk factors was added to give a combined total score for vascular risk burden.

Follow-up Assessment

The HRSD was administered at 12 and 24 weeks to assess the severity of depression. Remission was defined as an HRSD score of < 10. The assessment also measured the mood symptoms in the past 2 weeks.

Treatment Protocol

All subjects received treatment that followed a standardised treatment algorithm. Treatment-naïve patients were initially prescribed a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, with the dose titrated against clinical response. Antipsychotics or anxiolytics were added when clinically needed. If the subjects failed to respond to the first antidepressant, they were switched to another antidepressant or the treatment was augmented with a mood stabiliser, psychological treatment, or electroconvulsive therapy when clinically indicated. The study investigators monitored treatment to ensure that the clinical protocol was properly followed. Non-pharmacological intervention was provided if the subjects refused antidepressants.

Sample Size Estimation

A previous local study13 found that the mean ± standard deviation (SD) CVFT score of the subjects was 29.93 ± 9.89, and 37.73 ± 9.09 for the healthy controls. We assumed that the non-remitter group with late-onset depression at 24 weeks had impairment in executive function, therefore had similar impairment in CVFT to the patients in the above study13 and that the remitter group had similar performance to the healthy controls. A remitter group of 25 subjects with a non-remitter group of 25 subjects would have an α of 0.05 and β of 0.2 to detect the difference in CVFT scores between the groups. From the literature, approximately one-third of depressed elderly patients have persistent depression, so we estimated that one-third of the patients in this study would be non-remitters. Therefore, a minimum of 75 subjects were required for recruitment into the study.

Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Windows version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago [IL], US). The demographic data, as well as cognitive, behavioural, and functional measures between the remitters and non-remitters were compared using Mann-Whitney U test. Chi-square test was used to compare the frequencies of the categorical demographic data. The clinical characteristics, severity of mood symptoms, and cognitive scores were compared among the early remitters, late remitters, and non-remitters. Logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the significant factors associated with non-remission. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Of 120 patients with depression screened from January 2007 to December 2009, 109 fulfilled the recruitment criteria of late-onset depression, but 3 (2.8%) declined to participate. Of 106 subjects who completed the first assessment, 1 dropped out owing to a move to an old-age home in another catchment area. Therefore, a total of 105 subjects underwent assessment at 24 weeks.

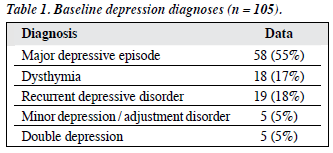

The mean (± SD) age of the subjects was 73.7 ± 6.1 years, and their mean duration of education was 3.9 ± 4.9 years. The female-to-male ratio was approximately 3:1. In all, 44 subjects (42%) had CDR scale scores of 0, and 61 (58%) had scores of 0.5. The baseline depression diagnoses are shown in Table 1.

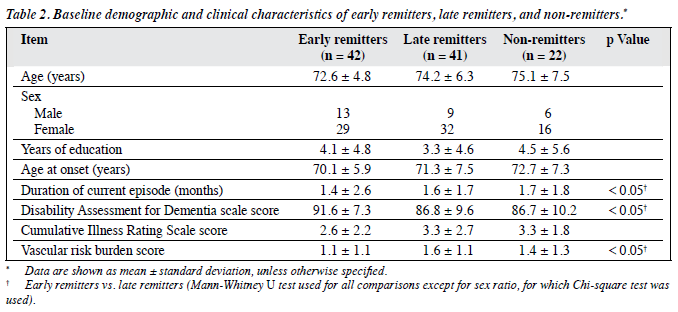

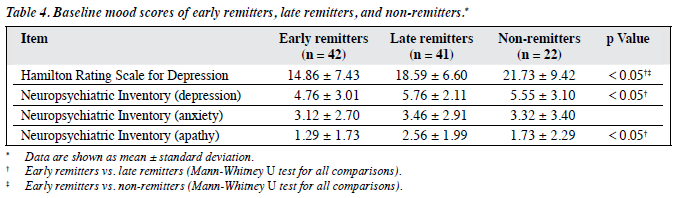

In all, 42 subjects (40%) had remission at 12 weeks and were categorised as early remitters, 41 (39%) who did not remit at 12 weeks but achieved remission at 24 weeks were categorised as late remitters, and 22 (21%) who had not achieved remission at 24 weeks were classified as non-remitters. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of these 3 groups are summarised in Table 2, whereas their baseline cognitive scores and mood scores are shown in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

These 3 groups did not statistically differ in age, years of education, and sex distribution. Early remitters had significantly better performance in baseline cognitive (global and executive domains and processing speed) and functional assessments than late remitters. Early remitters also had lower apathy and depression scores, shorter duration of current depressive episode, and less cardiovascular risk burden than late remitters.

Non-remitters had poorer performance in several domains of cognition, including episodic memory, attention and working memory, and processing speed than early remitters. Non-remitters also had higher depression scores than early remitters.

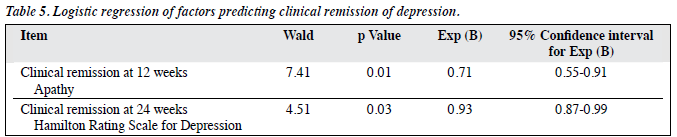

Independent variables, including cognitive test scores (MMSE, ADAS-Cog, delayed recall test, CVFT, VADS test, TMT), functional assessment score (DAD scale), mood scores (HRSD, NPI-apathy), cardiovascular risk burden, and duration of current depressive episode were examined to look for predictors of remission at 12 and 24 weeks. Regression analysis found that apathy score was the only significant factor predicting remission at 12 weeks, and depression score was the only significant factor predicting remission at 24 weeks (Table 5).

Discussion

This study found that a subgroup of depressed patients with higher cardiovascular risk burden, more executive dysfunction, and higher apathy and depression severity scores had a lower remission rate at 12 weeks than those with a lower burden of illness. Several studies have shown that a large number of patients with late-life depression fail to respond or respond partially to treatment, particularly those with executive impairment. These results add to previous findings of an association between prefrontal executive functions and treatment response in elderly patients with depression.6,8,20-23 The clinical characteristics of the late remitters were similar to those of elderly people with vascular depression. Prospective studies have suggested that vascular pathology appears to be associated with a more persistent and worsening course of depression.24-26 These findings suggest that vascular depression is an important clinical entity as it may result in acquired and lasting dysfunction in both affect and cognition.

Half of the non-remitters at 12 weeks achieved clinical remission at 24 weeks. Apathy and vascular burden were associated with a lower remission rate at 12 weeks but did not affect outcome at 24 weeks. Depression severity, slowing of processing speed, and lower episodic and working memory scores were associated with non- remission at 24 weeks. Another study reported a strong effect of baseline cognitive processing speed, executive function, episodic memory, and language processing as well as vascular burden when comparing patients who achieved depression remission with those who did not.27 Apart from executive dysfunction, some studies also found that memory impairment related to a poor remission rate. Higher rates of verbal preservation and poor simple auditory working memory span were associated with a lower rate of treatment remission over 3 months.8 Slower processing speed and verbal memory impairment were associated with a lower treatment response at 1 year.28

This study found that severity of baseline apathy and depression predicted the treatment response at 12 and 24 weeks. The influence of cognitive deficits (e.g. processing speed, executive function, and episodic memory) on clinical remission in this study became insignificant after controlling for the effects of mood symptoms. However, the small group size of non-remitters might limit the power of logistic regression to detect other predicting factors of remission, although significant differences in cognitive test scores between remitters and non-remitters were found. A study that examined the trajectories of treatment response in late-life depression found that higher baseline depression score was a significant factor for slow response and non- response after acute treatment for 12 weeks.29 However, another study did not identify the association between depression severity and magnitude of treatment response at 1 year.28 The difference in findings suggests that different factors might influence the treatment response in short and long term.

Most studies have reported the short-term treatment response, for example, at 3 months. As elderly patients might take longer to respond to treatment, this study also investigated the treatment response at 6 months in order to provide a more complete clinical picture. Subjects with poorer baseline episodic memory were found to have poorer outcome at 6 months. Non-remitters might represent a subgroup of patients with amnestic multi-domain mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with significant depressive symptoms or elderly people who have prodromal dementia with depression. Depression in patients with MCI, particularly those who subsequently progress to dementia, is more persistent and possibly refractory to antidepressant therapy.30,31 A study32 suggested that depression was predictive of progression from amnestic MCI (aMCI) to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and treatment with donepezil delayed progression to AD among depressed patients with aMCI. It would be interesting to follow-up the non-remitters for future progression of cognitive decline or treatment response to cholinesterase inhibitors.

Prognosis for late-onset depression is complicated by age-related brain changes that may contribute to persistent depression. Abnormalities of mood-critical structures in the frontostriatal and hippocampal regions appear to play a role in slowing and limiting an individual’s recovery from depression. Alexopoulos et al33 speculated that impairment in frontal structures underlying executive dysfunction results in reduced inhibitory control of limbic centres predisposing to persistence of depressive symptoms. Neuropsychological measures of executive functions and episodic memory can identify the cognitive deficits associated with this pathology.

The ‘vascular depression’ hypothesis has served as the conceptual background for further sub-classification of old-age depression. One group of investigators further described a vascular depression subtype, subcortical ischaemic depression (SID), and defined it as major depression with magnetic resonance imaging evidence of subcortical lesions.34 Although many patients with DED syndrome also meet the criteria for SID or other ‘vascular depression syndromes’, DED syndrome focuses on a functional abnormality rather than an anatomical one, thus extending beyond the vascular depression concept. Differences in aetiology have been postulated for SID and DED syndrome. It has been proposed that SID is due to vascular disease, whereas DED syndrome is caused by age-related changes and degenerative brain disease as well as vascular disease.35 The results from the current study identified 2 subgroups of patients with DED syndrome based on the subjects’ clinical presentation and remission rate. One group had a late response to treatment and the clinical characteristics were compatible with SID. These patients had significantly higher cardiovascular risk burden, based on the clinical history, and were more apathetic with more functional impairment. The non-remitters had features of DED syndrome, which might have an underlying degenerative process, and presented with co-occurrence of depression and MCI. These patients had significant impairment in episodic memory and executive function at baseline, while the clinical history of cardiovascular disease was not significantly increased compared with early remitters. These patients might have a more generalised degeneration process affecting more regions than the frontal-subcortical structures. Although the 2 proposed DED syndrome subgroups had common features such as executive dysfunction and depressive mood, their trajectories to clinical remission of depression seemed to be different.

These results highlight the importance of identifying elderly depressed patients who may be resistant or slow responders to treatment, and support that DED syndrome is associated with poorer prognosis. Depressed patients with executive dysfunction may require aggressive treatment and vigilant follow-up. Interventions specifically targeting executive deficits, including structured daily activities and functional support, may be used to remediate disability resulting from prefrontal dysfunction. Such interventions may interrupt the disability-depression downward spiral and promote recovery from depression.

One limitation of this study is that treatment for depression was not strictly controlled and compliance was not known. However, as the algorithm attempts to replicate a naturalistic treatment approach, the great variability of treatment may be more representative of real-world outcomes than results based on treatments modelled on clinical trials. Yet, even a naturalistic algorithm does not adequately reflect the manner in which most depressed older adults are treated in the community, which may be best approached by large community-based studies. Another limitation is the lack of radiological data to assess the severity of vascular lesions and substantiate the diagnosis of SID. Moreover, the group size of the non-remitters at 24 weeks might be too small to detect the prognostic factors for clinical remission in the short term by logistic regression.

Declaration

The authors declared no financial support or conflict of interest in relation to this study.

References

- Cole MG, Bellavance F, Mansour A. Prognosis of depression in elderly community and primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 1999;56:1182-9.

- Hybels CF, Steffens DC, McQuoid DR, Rama Krishnan KR. Residual symptoms in older patients treated for major depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:1196-202.

- Flint AJ, Rifat SL. The effect of sequential antidepressant treatment on geriatric depression. J Affect Disord 1996;36:95-105.

- Kok RM, Nolen WA, Heeren TJ. Outcome of late-life depression after 3 years of sequential treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009;119:274- 81.

- Schneider LS. Pharmacological considerations in the treatment of late life depression. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry 1996;4(Suppl):S51-65.

- Kalayam B, Alexopoulos GS. Prefrontal dysfunction and treatment response in geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:713-8.

- Alexopoulos GS. Role of executive function in late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(Suppl 14):S18-23.

- Potter GG, Kittinger JD, Wagner HR, Steffens DC, Krishnan KR. Prefrontal neuropsychological predictors of treatment remission in late-life depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004;29:2266-71.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982;140:566- 72.

- Chiu HF, Lee HC, Chung WS, Kwong PK. Reliability and validity of the Cantonese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination: preliminary study. J Hong Kong Coll Psychiatrists 1994;4:25-8.

- Chu LW, Chiu KC, Hui SL, Yu GK, Tsui WJ, Lee PW. The reliability and validity of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog) among the elderly Chinese in Hong Kong. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2000;29:474-85.

- Lam LC, Ho P, Lui VW, Tam CW. Reduced semantic fluency as an additional screening tool for subjects with questionable dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2006;22:159-64.

- Reiran RM, Wolfson D. Category test and trail making test as measures of frontal lobe functions. Clin Neuropsychol 1995;9:50-6.

- Mok CC, Siu AM, Chan WC, Yeung KM, Pan PC, Li SW. Functional disabilities profile of Chinese elderly people with Alzheimer’s disease — a validation study on the Chinese version of the disability assessment for dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2005;20:112- 9.

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56-62.

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308- 14.

- Leung VP, Lam LC, Chiu HF, Cummings JL, Chen QL. Validation study of the Chinese version of the neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:789-93.

- Conwell Y, Forbes NT, Cox C, Caine ED. Validation of a measure of physical illness burden at autopsy, the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:38-41.

- Alexopolous GS, Meyers BD, Young RC, Kalayam B, Kakuma T, Gabrielle M, et al. Executive dysfunction and long-term outcomes of geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:285-90.

- Kiosses DN, Klimstra S, Murphy C, Alexopoulos GS. Executive dysfunction and disability in elderly patients with major depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;9:269-74.

- Bella R, Pennisi G, Cantone M, Palermo F, Pennisi M, Lanza G, et al. Clinical presentation and outcome of geriatric depression subcortical ischemic vascular disease. Gerontology 2010;56:298-302.

- Morimoto SS, Gunning FM, Murphy CF, Kanellopoulos D, Kelly RE, Alexopoulos GS. Executive function and short-term remission of geriatric depression: the role of semantic strategy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;19:115-22.

- Simpson S, Baldwin RC, Jackson A, Burns AS. Is subcortical disease associated with a poor response to antidepressants? Neurological, neuropsychological and neuroradiological findings in late-life depression. Psychol Med 1998;28:1015-26.

- Steffens DC, Bosworth HB, Provenzale JM, MacFall JR. Subcortical white matter lesions and functional impairment in geriatric depression. Depress Anxiety 2002;15:23-8.

- Baldwin RC, Jeffries S, Jackson A, Sutcliffe C, Thacker N, Scott M, et al. Treatment response in late-onset depression: relationship to neuropsychological, neuroradiological and vascular risk factors. Psychol Med 2004;34:125-36.

- Sheline YI, Pieper CF, Barch DM, Welsh-Bohmer K, McKinstry RC, MacFall JR, et al. Support for the vascular depression hypothesis in late-life depression: results of a 2-site, prospective, antidepressant treatment trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:277-85.

- Story TJ, Potter GG, Attix DK, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Steffens DC. Neurocognitive correlates of response to treatment in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;16:752-9.

- Gildengers AG, Houck PR, Mulsant BH, Dew MA, Aizenstein HJ, Jones BL, et al. Trajectories of treatment response in late-life depression: psychosocial and clinical correlates. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;25(4 Suppl 1):S8-13.

- Modrego PJ, Ferrández J. Depression in patient with mild cognitive impairment increases risk of developing dementia of Alzheimer type: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1290-3.

- Li YS, Meyer JS, Thornby J. Longitudinal follow-up of depressive symptoms among normal versus cognitively impaired elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:718-27.

- Lu PH, Edland SD, Teng E, Tingus K, Petersen RC, Cummings JL, et al. Donepezil delays progression to AD in MCI subjects with depressive symptoms. Neurology 2009;72:2115-21.

- Alexopoulos GS, Kiosses DN, Heo M, Murphy CF, Shanmugham B, Gunning-Dixon F. Executive dysfunction and the course of geriatric depression. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:204-10.

- Krishnan KR, Taylor WD, McQuoid DR, MacFall JR, Payne ME, Provenzale JM, et al. Clinical characteristics of magnetic resonance imaging-defined subcortical ischemic depression. Biol Psychiatry 2004;55:390-7.

- Alexopoulos G. The vascular depression hypothesis: 10 years later. Biol Psychiatry 2006;60:1304-5.