East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2014;24:169-173

SPECIAL COMMUNICATION

中国首发精神分裂症临床试验(CNFEST):背景和研究设计

韩雪、原岩波、于欣、赵靖平、王传跃、陆峥、杨甫德、邓红、武阳丰、GS Ungvari、项玉涛、赵凤琴

Dr Xue Han, MD, Peking University Sixth Hospital, Peking University Institute of Mental Health, Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Ministry of Health (Peking University), Beijing, China.

Dr Yan-Bo Yuan, MD, Peking University Sixth Hospital, Peking University Institute of Mental Health, Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Ministry of Health (Peking University), Beijing, China.

Dr Xin Yu, MD, Peking University Sixth Hospital, Peking University Institute of Mental Health, Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Ministry of Health (Peking University), Beijing, China.

Dr Jing-Ping Zhao, MD, Mental Health Institute, the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

Dr Chuan-Yue Wang, Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China.

Dr Zheng Lu, Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Dr Fu-De Yang, Center for Biological Psychiatry, Beijing Hui-Long-Guan Hospital, Beijing, China.

Dr Hong Deng, Mental Health Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan province, China.

Mr Yang-Feng Wu, the George Institute for Global Health at Peking University Health Science Center, Beijing, China.

Dr Gabor S. Ungvari, The University of Notre Dame Australia / Marian Centre, Perth, Australia.

Dr Yu-Tao Xiang, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Macao, China.

Dr Helen Fung-Kum Chiu, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Xin Yu, Peking University Sixth Hospital, Peking University Institute of Mental Health, Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Ministry of Health (Peking University), Huayuanbeilu 51, 100191, Haidian District, Beijing, China.

Tel: (86-10) 82801999; Email: yuxin@bjmu.edu.cn

Submitted: 15 May 2014; Accepted: 12 August 2014

Abstract

Schizophrenia is a complex illness with unknown aetiology and pathogenesis. Currently, a considerable number of patients with schizophrenia do not receive standardised and systematic treatment in China. In the past years, many controlled trials have been conducted in chronic schizophrenia. In contrast, research on first-episode schizophrenia is lacking. This paper describes the background and design of the Chinese First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial project — a multicentre, randomised, open-label clinical trial. A total of 600 first-episode schizophrenia patients were randomly divided into 3 groups and treated with risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine for 1 year. During the study period, only 1 medication change of the 3 antipsychotic medications was allowed.

Key words: Antipsychotic agents; Clinical trial; Schizophrenia

摘要

精神分裂症是一类病因和发病机制尚未明确的複杂疾病。目前在中国仍有很多精神分裂症患者 未能得到规範化和系统性治疗。近年已有很多研究在慢性精神分裂症患者中开展,而针对首发 精神分裂症患者的研究相对较少。本文阐述一个多中心、随机和开放性临床试验 ── 中国首发 精神分裂症临床试验(CNFEST)的背景和设计。共600例首发精神分裂症患者随机分配到3个 药物治疗组(利培酮、阿立哌唑和奥氮平)治疗一年。研究期间,患者在3个治疗药物内有1次 换药机会。

关键词:抗精神病药物、临床试验、精神分裂症

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a complex illness with various clinical manifestations and prognoses. It is generally believed that the shorter the duration of untreated psychosis, the better the prognosis.1,2 In order to improve the prognosis of schizophrenia, a number of studies3-5 have focused on its early intervention.

In China, a considerable number of schizophrenia patients do not receive standardised and systematic treatment; in fact, approximately 70% of the estimated 4.8 million persons with schizophrenia in China do not receive regular treatment, possibly due to the failure of psychiatrists to comply with the treatment guidelines and patients’ poor treatment adherence.6 Despite the availability of treatment guidelines,7,8 choosing the optimal antipsychotic medication for schizophrenia remains a major clinical challenge.9-11 Most randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in schizophrenia are only short-term studies and include only highly selected patients,12-16 therefore their findings are only partly relevant to clinical practice. Three recent large- scale drug trials3,4,17 were conducted under ‘real-world’ conditions. The CATIE4 and CUtLASS17 studies involved only chronic patients despite the fact that many confounding factors are associated with chronicity of schizophrenia. Only the EUFEST study3 was carried out in first-episode schizophrenia (FES), but the findings of this multicentre European study probably cannot be applied directly to the Chinese sociocultural context and psychiatric settings. Lack of data about the optimal treatment of schizophrenia in China gave the impetus to design a ‘real-world’, open-label RCT entitled the Chinese First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial (CNFEST) to be conducted in Chinese clinical settings. This study aimed to compare the long-term effectiveness and tolerability of olanzapine, aripiprazole, and risperidone in Chinese FES patients, as well as to identify the socio- demographic and clinical factors associated with treatment adherence, cognitive impairment, social dysfunction, and prognosis at 1-year follow-up.

Methods

Settings

This multicentre, randomised, open-label clinical trial was conducted from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2010. Six participating psychiatric centres located in North, West, East, and Central China were selected. These included Peking University Sixth Hospital (Beijing); Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University (Beijing); Huilongguan Hospital (Beijing); Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (Shanghai); West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Chengdu, Sichuan); and Mental Health Institute, Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (Changsha, Hunan).

Study Criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (1) both in- and out-patients, (2) both genders, (3) diagnosis of schizophrenia established with Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorder, patient edition, (4) aged between 18 and 45 years, (5) onset at age ≥ 15 years, (6) first episode of schizophrenia, (7) no previous psychiatric treatment (‘drug-naïve’ status), and (8) ability to understand the contents of interview and provide written informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) a history or diagnosis of major medical conditions, (2) a history of alcohol and / or drug abuse or dependence, and (3) contra-indication to olanzapine, aripiprazole, or risperidone.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the medical ethics committees of the 6 participating hospitals.

Treatment

A total of 600 FES patients were consecutively recruited in the study. They were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups, i.e. treatment with risperidone, aripiprazole, or olanzapine, by a computer-generated table, and then followed up for 1 year. During the follow-up period, if the treatment failed as judged by the investigators and / or the patient, the patients entered the next stage of the trial.

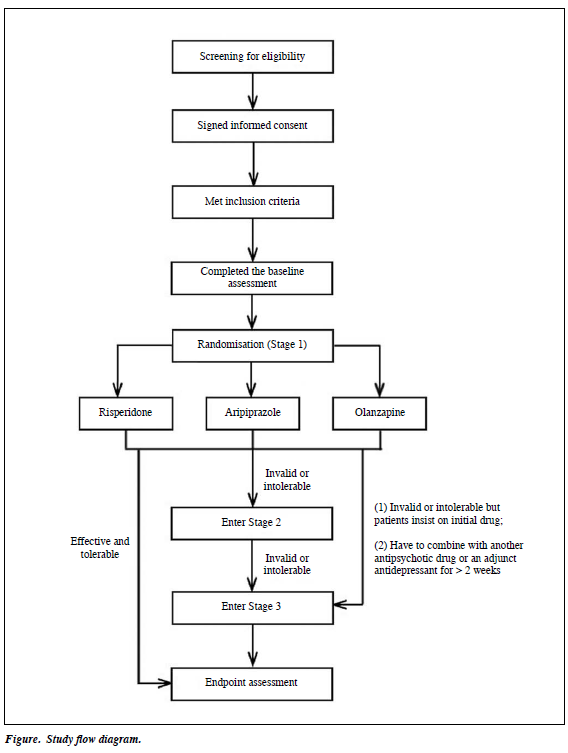

There were 3 stages of clinical intervention (Fig). In Stage 1, all 600 patients started antipsychotic monotherapy; antipsychotic doses were increased to a standard therapeutic range (3-6 mg risperidone, 15-30 mg aripiprazole, or 10-25 mg olanzapine per day) by the research psychiatrist in 2 weeks. Patients were assessed monthly by the research team for therapeutic effects and adverse events. During this stage, other antipsychotic medications were forbidden; if necessary, small doses of benzodiazepines (0.5-1.5 mg oral lorazepam or 2-4 mg oral or intramuscular clonazepam per day) could be prescribed for agitation and oral benzhexol (2-6 mg per day) or promethazine (25-75 mg per day) for extrapyramidal side-effects (EPS). At Stage 2, if no satisfactory effect was observed after at least 6 to 8 weeks but not more than 3 months (< 50% reduction on the total score of the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale [PANSS]) or intolerable adverse effects (severe EPS or weight gain > 10% of body weight) appeared, the research psychiatrist could change the antipsychotic to 1 of the other 2 study drugs while the monthly follow-ups continued. As in Stage 1, other antipsychotics were forbidden while the same adjunct medications could be administered. At Stage 3, pharmacotherapy could be switched to any other atypical antipsychotic including long-acting medications. Furthermore, a combination with other antipsychotics or a certain adjunctive antidepressant was allowed for patients who still could not reach satisfactory outcome after the previous 2 stages. Some patients were moved directly from Stage 1 to Stage 3 under special circumstances. For example, if the antipsychotic treatment was unsuccessful after 3 months (< 50% reduction on the PANSS score) or the weight gain exceeded 10% but the patient insisted on continuing the initial antipsychotic, then with the research psychiatrist’s consent, s/he could enter Stage 3. Also, if the antipsychotic drug used in Stage 1 had to be augmented with another antipsychotic or an adjunct antidepressant for > 2 weeks, patients had to skip Stage 2 and enter Stage 3. Patients who moved from Stage 1 to Stage 3 continued to be followed up for the rest of the 1 year.

Instrument and Evaluation

Basic socio-demographic and clinical data were collected with a form designed for the study. Duration of untreated psychosis was defined as the period between the onset of any obvious psychotic symptoms and the start of the antipsychotic treatment.

Mental state was assessed by trained psychiatrists at baseline and at 4, 8, and 13 weeks and then at 3-month intervals until the end of 1-year follow-up. An additional clinical assessment took place at the commencement of any medication change.

Symptom severity was evaluated with the PANSS18,19 and Clinical Global Impressions Severity and Improvement scales.20 Adverse events induced by antipsychotics were assessed using the Udvalg for Kliniske Undersøgelser side-effect scale.21 Treatment adherence was assessed with the 10-item version of Drug Attitude Inventory.22-24 Social functions were assessed using the Personal and Social Performance scale.25,26 Dropout was defined as discontinuation of treatment or withdrawing the consent to participate in the study.

Cognitive performance was evaluated at baseline, 6 months, and endpoint with a neuropsychological test battery comparable to the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB). The test battery included 5 tests of MCCB (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised [HVLT- R], Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–Revised [BVMT-R], Trail Making Test Part A, category fluency test, animal naming and Wechsler Memory Scale–spatial span subtest), and 8 alternative tests (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale digit symbol-coding subtest, symbol search subtest,27 Word sound fluency test, Grooved Pegboard Test, Color Trails Test, Stroop Color-Word Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test [64-item version],27-29 and paced auditory serial addition task) that assessed 5 cognitive domains: verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, speed of processing, motor skills, and executive function. Two alternative forms of HVLT-R and BVMT-R were used to control the potential learning effects at 6 months and endpoint.

There were 2 to 3 psychiatrists responsible for clinical assessment and another 2 to 3 psychiatrists for performing neuropsychological tests at each site. All interviewers attended a 1-week training workshop on use of the rating instruments prior to the study. Prior to the main study, a pilot study involving 20 schizophrenia patients was conducted. The inter-rater reliability of all instruments was satisfactory (intraclass correlation coefficients or kappa values > 0.75).

Laboratory Tests

Blood samples were collected at baseline, at the time points of medication changes, and at the endpoint. Blood samples were used to monitor adverse drug effects such as metabolic syndrome and liver or kidney dysfunction. Blood samples were stored and would be used to detect biomarkers at a later stage of the study.

Data Management

An online research database was established for real- time data transmission, monitoring, management, and task assignment. Data collected from each study site were entered into the central database and saved by data managers. Information recorded with the paper version of the data collection forms was double-entered and checked by a data entry company.

Conclusion

Results of this study are expected to be published in 2015. We believe that the findings will have important implications for developing a standardised treatment strategy for FES. The next stage of trial will be conducted to examine contributors to relapse of FES patients.

Declaration

This study was supported by National Key Project of Scientific and Technical Supporting Programs from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. 2007BAI17B04). The Clinical trials.gov ID of the study is NCT01057849.

References

- Penttilä M, Miettunen J, Koponen H, Kyllönen M, Veijola J, Isohanni M, et al. Association between the duration of untreated psychosis and short- and long-term outcome in schizophrenia within the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Schizophr Res 2013;143:3-10.

- Chang WC, Hui CL, Tang JY, Wong GH, Chan SK, Lee EH, et al. Impacts of duration of untreated psychosis on cognition and negative symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia: a 3-year prospective follow- up study. Psychol Med 2013;43:1883-93.

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Derks EM, Bitter I, Libiger J, Kahn RS, et al. Efficacy of antipsychotic drugs against hostility in the European First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial (EUFEST). J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:955-61.

- Koranek AM, Smith TL, Mican LM, Rascati KL. Impact of the CATIE trial on antipsychotic prescribing patterns at a state psychiatric facility. Schizophr Res 2012;137:137-40.

- Larson MK, Walker EF, Compton MT. Early signs, diagnosis and therapeutics of the prodromal phase of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Expert Rev Neurother 2010;10:1347-59.

- Phillips MR. Characteristics, experience, and treatment of schizophrenia in China. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2001;3:109-19.

- Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, Möller HJ, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, Part 1: acute treatment of schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry 2005;6:132-91.

- Tandon R, Belmaker RH, Gattaz WF, Lopez-Ibor JJ Jr, Okasha A, Singh B, et al. World Psychiatric Association Pharmacopsychiatry Section statement on comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2008;100:20-38.

- Fleischhacker WW, Derks E, Kahn RS. Interpreting treatment trials in schizophrenia patients: lessons learned from EUFEST. Schizophr Res 2012;138:39-40.

- Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:31-41.

- 1 Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, Kane JM, Leucht S. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta- analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull 2009;35:443- 57.

- Klieser E, Lehmann E, Kinzler E, Wurthmann C, Heinrich K. Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of risperidone versus clozapine in patients with chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;15(1 Suppl 1):45S-51S.

- Rosenheck R, Perlick D, Bingham S, Liu-Mares W, Collins J, Warren S, et al. Effectiveness and cost of olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:2693-702.

- Akhondzadeh S, Safarcherati A, Amini H. Beneficial antipsychotic effects of allopurinol as add-on therapy for schizophrenia: a double blind, randomized and placebo controlled trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2005;29:253-9.

- Josiassen RC, Joseph A, Kohegyi E, Stokes S, Dadvand M, Paing WW, et al. Clozapine augmented with risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:130-6.

- Möller HJ, Riedel M, Jäger M, Wickelmaier F, Maier W, Kühn KU, et al. Short-term treatment with risperidone or haloperidol in first- episode schizophrenia: 8-week results of a randomized controlled trial within the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2008;11:985-97.

- Jones PB, Barnes TR, Davies L, Dunn G, Lloyd H, Hayhurst KP, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect on Quality of Life of second- vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:1079-87.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987;13:261-76.

- Si TM, Yang JZ, Shu L, Wang XL, Kong QM, Zhou M, et al. The reliability, validity of PANSS and its implication [in Chinese]. Chin Ment Health J 2004;18:45-7.

- Guy W. Clinical global impressions, in ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology (revised). Rockville, US: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976: 217-21.

- Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The UKU side effect rating scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1987;334:1-100.

- Nielsen RE, Lindström E, Nielsen J, Levander S. DAI-10 is as good as DAI-30 in schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2012;22:747- 50.

- Cheng HL, Yu YW. Validation of the Chinese version of “the Drug Attitude Inventory” [in Chinese]. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 1997;13:370- 7.

- Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med 1983;13:177-83.

- Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;101:323-9.

- Si TM, Shu L, Tian CH, Sun YA, Yan J, Cheng J, et al. Evaluation of reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Personal and Evaluation of Social Performance Scale in patients with schizophrenia [in Chinese]. Chin Ment Health J 2009;23:790-4.

- Shi C, Yu X, Wu ZY, Robert KH, Jin H, Thomas DM, et al. Neuropsychological feasibility study among HIV+/AIDS subjects in China. [in Chinese]. Chin Ment Health J 2005;19:343-5.

- Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:203-13.

- Kern RS, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Baade LE, Fenton WS, Gold JM, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 2: co- norming and standardization. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:214-20.