Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2009;19:4-10

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr CB Osman, MD, MMedPsych, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Malaysia.

Dr MM Badli, MD, MMedPsych, Department of Psychiatry, Army Hospital, Kuala Lumpur.

Dr O Ainsah, MD, MMedPsych, PhD, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Malaysia.

Dr A Suthahar, MBBS, MMedPsych, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Malaysia.

Dr R Salmi, MD, MMedPsych, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Malaysia.

Ms NM Azlinawati, BMedMSc Psychol, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Malaysia.

Dr SH Almashoor, MBBS, DPM, MRCPsych, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Malaysia.

Address for correspondence: Dr Che Bakar Osman, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Malaysia.

Tel: (60-3) 7726 5446; Fax: (60-3) 5544 2831

E-mail: ocbaaaah@yahoo.com.my

Submitted: 21 July 2008; Accepted: 9 September 2008

Abstract

Objective: To examine quality of life in relation to demographic profiles and clinical factors in patients with schizophrenia and major mood disorder in remission.

Participants and Methods: This was a cross-sectional study conducted in the outpatient psychiatric clinic at the Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia from June 2002 to December 2002. All the patients fulfilled the study inclusion criteria. Their psychiatric diagnoses were made by their treating psychiatrists based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition). The remission state was determined using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale or Young Manic Rating Scale for schizophrenia, depression or manic patients, respectively. The patients were subsequently subjected to a 36-item short-form Health Survey for quality-of-life assessment.

Results: The quality of life of patients with schizophrenia (n = 92) was no different from those with major mood disorder (n = 71) [p > 0.05]. Quality of life in terms of overall mental health among patients with schizophrenia was significantly and positively associated with ethnicity, employment status, and type of antipsychotic drug treatment (p < 0.05). Being Chinese and employed was associated with better quality of life in terms of overall mental health. Quality of life pertaining to overall physical health of patients with schizophrenia was better in those who were employed and being treated with atypical antipsychotics. Quality of life in patients with major mood disorder was significantly associated with ethnicity, type of antidepressants used, and number of admissions (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: Though schizophrenia has often been considered a chronic disease with poor outcome, our study showed that quality of life of the patients was comparable to those with major mood disorder.

Key words: Mood disorders; Quality of life; Schizophrenia

摘要

目的:檢視病情緩解的精神分裂症和情感性疾患患者 與人口統計和臨床因 素有關的生活質素。

參與者與方法:馬來西亞科班薩大學(Universiti Kebangsaan)醫院精神科門診診所於2002年 6月至12月間進行橫斷面研究。所有患者均合乎研究資格,並由負責治療的醫生以《精神疾病診斷和統計手冊》第四版確診,且使用簡化版精神病評定量表、漢密爾頓抑鬱量表,以及青少年狂躁量表分別評估精神分裂症、抑鬱或狂躁患者的病情減輕程度。患者隨後參與SF-36調查以評估其生活質素。

結果:精神分裂症(n = 92)和情感性疾患(n = 71)患者的生活質素相若(p > 0.05);而前者在整體精神健康方面則與種族、就業情況和抗精神病藥物種類呈正相關(p < 0.05)。華人就業人士整體精神健康越好,生活質素便越高;整體身體健康方面,則以就業和服用非典型抗精神病藥物的精神分裂症患者較佳。情感性疾患患者的生活質素則與種族、服用抗抑鬱劑種類,以及入院次數相關(p < 0.05)。

結論:雖然精神分裂症常被定為一種慢性且不易醫治的疾病,但研究顯示患者的生活質素與情感性疾患患者相若。

關鍵詞:心境障礙、生活質素、精神分裂症

Introduction

According to a study among patients with schizophrenia, the quality of life (QOL) living in the community was less satisfactory than that of healthy controls in the general population.1 Larsen and Gerlach,2 however, found no differences when their patients were compared to the general population. Depression is a common chronic and recurrent illness, which adversely affects longevity and QOL both during the episode and potentially for the remainder of life.3 It has been estimated that, by 2020, major depression will be the second most frequent cause of disability in the world.4

Conventional versus atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants have different side-effects and therapeutic profiles, both of which influence QOL.5,6 Although the effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs against positive symptoms has been demonstrated in many studies, their different effects on QOL and on long-term compliance remain unclear.7 A study by Tempier and Pawliuk8 on the influence of novel antipsychotics reported that recipients of these drugs scored lower in terms of QOL than those taking older drugs. Another study, however, found that taking atypical antipsychotics was associated with a better QOL than subjects receiving conventional antipsychotics.7

The objective of this study was therefore to examine the relationship between QOL of patients with schizophrenia and major mood disorder (both in remission), in relation to demographic profiles, illness factors, and types of drugs (typical and atypical) being used.

Study Design

Instruments

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in the outpatient psychiatric clinic at the Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan, Malaysia. Study instruments included: (1) the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)9; (2) the 17-item Hamilton Depressive Scale (HAM-D)10; (3) the Young Manic Rating Scale (YMRS)11; and (4) the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36-item Short Form (SF-36) questionnaire.12

Patients with schizophrenia and major mood disorder who attended the psychiatric clinic from June 2002 to December 2002 and fulfilled the inclusion criteria of this study were recruited. After explanation, informed consent was obtained from each participant. They were clinically assessed by the authors. Subjects with schizophrenia, depression or mania were considered to be in remission if they scored 9 or below, 7 or below, and 5 or below in the BPRS, HAM-D, or YMRS, respectively. These scores have been used previously to determine the state of remission of schizophrenia, depression and mania, respectively.13-15 The diagnosis of schizophrenia and major mood disorder (depression and manic state) was made by the treating psychiatrist as well as the authors based on the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV).16 Patients were subsequently subjected to the SF-36 questionnaire to assess their QOL.

Subjects

All patients attending the psychiatric clinic were registered. Simple random sampling of 1 in 10 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or major mood disorder was performed. They were subsequently assessed by the investigator for the DSM-IV diagnosis and remission criteria with BPRS, HAM-D, and YMRS.

Inclusion criteria for eligibility were that the subjects had to be 18 to 65 years old, have sufficient command of the Malay or English, and did not have any underlying physical illness. Exclusion criteria were that patients were current substance / drug abusers, had a history of brain injury, and were mentally retarded. Patients were also excluded if their BPRS score exceeded 9, their HAM-D score exceeded 7, or their YMRS score exceeded 5.

The SF-36 Health Survey was developed for the MOS and had been tested and validated extensively. It is a multilingual questionnaire; the original was in English, but it had been translated and used in the Bahasa Malaysia. We used the translated Bahasa Malaysia version, which was reported to have satisfactory internal consistency.17

In this study, the inter-rater reliability of the scales was ascertained by randomly taking a ratio of 1:10 patients, who were re-rated by the researchers independently. The agreement of kappa (κ) was calculated and found to be 1.

Statistical Analyses

The data were analysed using version 11.5 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. The independent sample t test and the Chi-square test were used as appropriate to determine significant differences between the 2 groups, namely patients with schizophrenia and major mood disorder. Non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test) were performed for data which were not normally distributed. In addition to the independent sample t tests, analysis of variance was used to examine the difference between the 3 ethnic groups (Malays, Chinese, and Indians) for continuous variables that were normally distributed; the data were then analysed by multiple linear regression.

Results

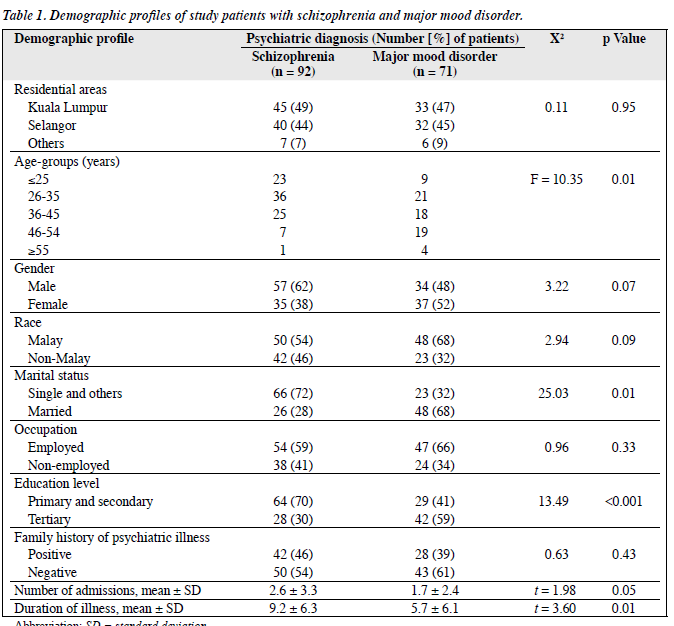

A total of 92 patients with schizophrenia and 71 with major mood disorder were recruited from a total of 4,585 patients attending the psychiatric clinic (Table 1). These included 2,462 with schizophrenia and 2,123 with major mood disorder. Randomised sampling was performed with a ratio of 1:10, and yielded a total of 458 patients (246 with schizophrenia and 212 with major mood disorder). In all, 272 (59%) did not meet the inclusion criteria of the study, leaving 186 eligible patients (106 with schizophrenia and 80 with major mood disorder), of whom 23 (12%) declined to participate.

Thus, a total of 163 (36%) patients fulfilled all the criteria and completed the questionnaire. They consisted of 92 (56%) diagnosed as having schizophrenia and 71 (44%) with major mood disorder. Of these 163 patients, 21 (13%) had bipolar mood disorder and 50 (31%) had major depression.

The 23 patients who declined to participate did not differ significantly in terms of age, gender, race, and psychiatric diagnoses from those who participated.

Medication

The antipsychotics mostly prescribed to patients were atypical agents (54%), while the remainder received typical antipsychotics. Among the former, 27% were prescribed risperidone and 22% olanzapine; the most common typical drug prescribed was haloperidol (14%).

Patients with Schizophrenia

Quality of Life among Various Ethnic Groups

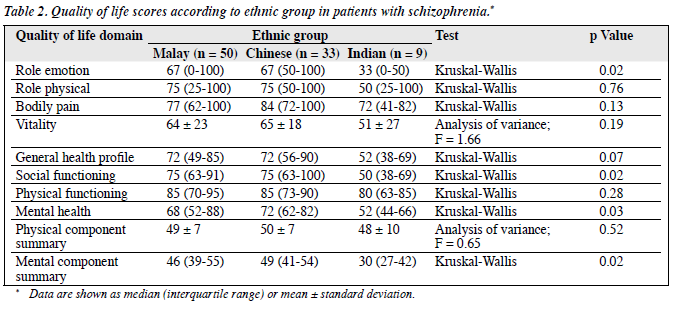

In patients with schizophrenia, there was significant difference in role emotion, social functioning, mental health, and mental component summary in relation to ethnicity (p < 0.05) [Table 2]. In terms of role emotion and social functioning, the Chinese and Malays were better than the Indians, whilst in terms of mental health and overall mental health, the Chinese were better than the other races.

Relationship between Quality of Life and Occupational Status

There was a significant difference in vitality, social functioning, mental health, and the mental component summary in relation to the occupational status (p < 0.05). Employed patients were better than the unemployed patients in terms of vitality, social functioning, mental health, and overall mental health.

Relationship between Quality of Life and Other Variables

Among patients with schizophrenia, there was no significant difference in QOL related to age-group, marital status, education level, duration of illness, gender, family history of psychiatric illness, and number of prior admissions (p > 0.05).

Patients with Major Mood Disorder

Quality of Life among Various Ethnic Groups

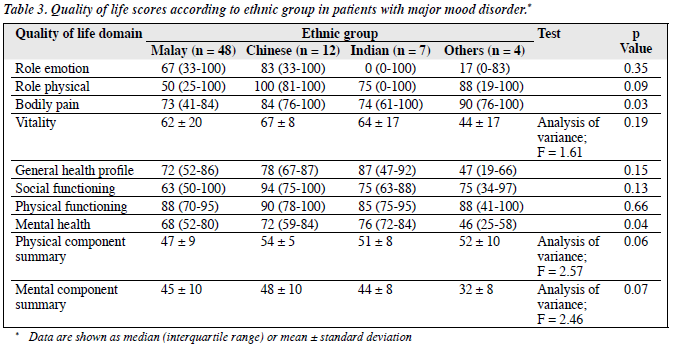

There was a significant difference in QOL in terms of bodily pain and mental health in relation to ethnicity (p < 0.05); the Chinese were better than Malays and Indians in terms of bodily pain. The Malays, Chinese, and Indians were better than the other minorities in terms of mental health (Table 3).

Relationship between Quality of Life and Antidepressant Medications

There was a significant difference in QOL in terms of role emotion in relation to antidepressant medications (p < 0.03). The newer antidepressants appeared better than tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) in terms of role emotion.

Relationship between Quality of Life and Other Variables

There was no significant relationship between QOL and occupational status, age-group, marital status, education level, duration of illness, family history of psychiatric illness, and gender in patients with major mood disorder.

Comparison of Quality of Life of Patients

In summary, there was no significant difference in terms of QOL between patients with schizophrenia and major mood disorder (p > 0.05). Patients with schizophrenia or major mood disorder who were in remission showed no significant difference in terms of their QOL.

Multivariate Analysis

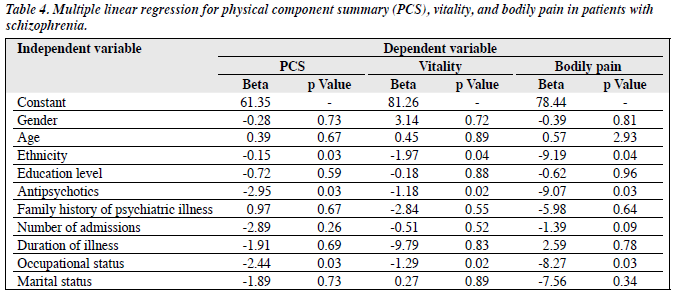

Scores of QOL in schizophrenic patients yielded statistically significant differences with respect to ethnic groups, antipsychotics, and occupational status (Table 4). Patients with schizophrenia who were employed, treated with atypical antipsychotics, and of Chinese had higher QOL scores in terms of overall physical health, vitality, and bodily pain (p < 0.05).

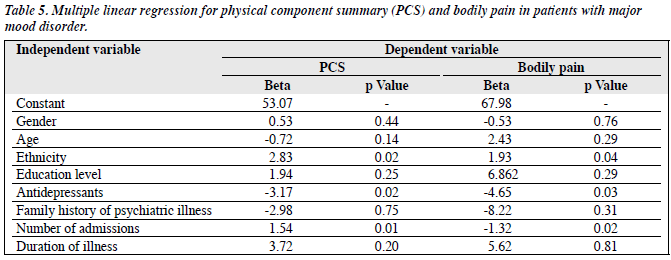

Among patients with major mood disorder, factors that were statistically significant for QOL included ethnicity, antidepressant medications, and the number of admissions (p < 0.05) [Table 5]. The fewer the prior admissions, the higher the QOL score in terms of physical component summary. Non-Malays and those who had fewer prior admissions had higher QOL scores in terms of overall physical health and bodily pain. Those taking newer antidepressants were better off than those taking TCAs in terms of bodily pain and overall physical health.

Discussion

This was a cross-sectional study examining QOL among patients with schizophrenia and major mood disorder in remission, in relation to their demographics, illness and treatment factors. The duration of illness was found to be significant in relation to the psychiatric diagnosis (p < 0.05). The majority of patients with schizophrenia (86%) had an illness duration exceeding 2 years (mean ± standard deviation, 9.2 ± 6.3 years), which was consistent with previous local studies.18,19 Patients with major mood disorder had shorter mean illness durations (5.7 ± 6.1 years). Atkinson et al20 also reported that schizophrenia had a longer duration than depression and bipolar disorder, consistent with schizophrenia being a more chronic illness than mood disorder (which has a better outcome).

The antipsychotics prescribed to most patients (54%) were atypical agents, the remainder received conventional antipsychotics. Regarding antidepressants, 62% of the depressed patients received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): sertraline in 22%, fluvoxamine in 20%, and fluoxetine in 16%. In this study, most patients with schizophrenia were treated with atypical antipsychotics, as these are associated with improved efficacy and better tolerance than the older, conventional antipsychotics. Moreover, patients treated with the former have been reported to enjoy significantly improved QOL.21

Antipsychotics and occupational status were found to be statistically significant indicators of QOL. Patients with schizophrenia had significantly different role emotion, social functioning, mental health, and mental component summary in relation to the ethnicity (p < 0.05). The role emotion, social functioning, and mental health are scales of the mental component of QOL. Hence there was a significant difference between ethnicity in relation to the mental health component of QOL. Chinese and Malays were better than the Indians in terms of role emotion, and the Chinese were also better in terms of mental health and overall mental components. The Chinese with schizophrenia had the highest emotional well-being compared to the other races. However, compared with other ethnic groups, the relatively small number of Indians in this study (particularly with schizophrenia) could well be a bias.

A favourable factor noted in the Chinese with schizophrenia was that they were mostly taking atypical antipsychotics (70%) in contrast to the Malays and Indians. There was a significant difference between the ethnic groups in relation to antipsychotic medication. The effects of ethnicity may have been confounded by that atypical antipsychotics are associated with better QOL.5 Quality of life among patients with schizophrenia was not significantly related to age, marital status, education level, duration of illness, gender, family history of psychiatric illness, or the number of admissions. Those who were employed and receiving atypical antipsychotics had better QOL.

As for patients with major mood disorder, QOL was significantly associated with race, antidepressant medication, and number of admissions. The Chinese were better than the Malays and Indians in terms of bodily pain. Patients taking the newer antidepressants reported less role limitation because of emotional problems. However these results should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample of TCA recipients. There was no significant relationship between QOL and occupational status, age, marital status, education level, duration of illness, family history of psychiatric illness, and gender among the patients with major mood disorder. In the multivariate analysis, the QOL in patients with major mood disorder was associated with ethnicity, newer antidepressants, and the number of admissions. Nevertheless these findings need cautious interpretation, as this was a cross-sectional study in only 1 hospital and might not apply to other populations.

The SF-36 is a useful tool in evaluating the QOL, it also has limitations. The subscales are not aggregated to give the global score.16 Mean scores were obtained for each subscale, which tends to distort the results due to outlying values. The questionnaire did not contain age- specific questions and might not be appropriate for all ages. The bodily pain scale has been reported to show low convergent validity with severity of illness and independent pain scores.16 It is therefore proposed that other subjective QOL questionnaires like the WHOQOL-BREF21 should be considered in future studies. The SF-36 used in this study had not been validated for the Malaysian population (taking into consideration the diversity of cultural and religious beliefs). This might affect the validity of the findings. Perhaps future research could focus on this issue and in turn provide a more accurate picture of QOL in patients with psychiatric disorders.

In conclusion, though schizophrenia has often been considered a chronic disease with a poor outcome, our study showed that the QOL of these patients and those with major mood disorder was quite comparable, reflecting significant impact of major mental disorder on QOL.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Director of Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia and all patients who had agreed to participate in this study.

References

- Lehman AF, Ward NC, Linn LS. Chronic mental patients: the quality of life issue. Am J Psychiatry 1982;139:1271-6.

- Larsen EB, Gerlach J. Subjective experience of treatment, side-effects, mental state and quality of life in chronic schizophrenic out-patients treated with depot neuroleptics. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:381-8.

- Pyne JM, Patterson TL, Kaplan RM, Gillin JC, Koch WL, Grant I. Assessment of the quality of life of patients with major depression. Psychiatr Serv 1997;48:224-30.

- World Health Organization. World health report. Geneva: WHO; 2004.

- Pinikahana J, Happell B, Hope J, Keks NA. Quality of life in schizophrenia: a review of the literature from 1995 to 2000. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2002;11:103-11.

- Goldney RD, Fisher LJ, Wilson DH, Cheok F. Major depression and its associated morbidity and quality of life in a random, representative Australian community sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2000;34:1022-9.

- Franz M, Lis S, Plüddenman K, Gallhofer B. Conventional versus atypical neuroleptics: subjective quality of life in schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 1997;170:422-5.

- Tempier R, Pawliuk N. Influence of novel and conventional antipsychotic medication on subjective quality of life. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2001;26:131-6.

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Report 1962;10:799-812.

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967;6:278-96.

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978;133:429-35.

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourme CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF 36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473-83.

- Browne S, Clarke M, Gervin M. Determinant of quality of life at first presentation with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:173-6.

- Pintor L, Gastó C, Navarro V, Torres X, Fañanas L. Relapse of major depression after complete and partial remission during a 2-year follow- up. J Affect Disord 2003;73:237-44.

- Cooke RG, Robb JC, Young LT, Joffe RT. Well-being and functioning in patients with bipolar disorder assessed using the MOS 20-ITEM short form (SF-20). J Affect Disord 1996;39:93-7.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Sararaks S, Rugayah B, Azman AB, Karuthan C, Low LL. Quality of life — how do Malaysian asthmatics fare? Med J Malaysia 2001;56:350-8.

- Abdullah AF. Features association with compliance in schizophrenia patients at Hospital Kuala Lumpur [thesis]. Malaysia: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia; 2000.

- Arif NH. Chronic schizophrenia and family burden [thesis]. Malaysia: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia; 1991.

- Atkinson M, Zibin S, Chuang H. Characterizing quality of life among patients with chronic mental illness: a critical examination of the self- report methodology. Am J Psychiatry 1997;154:99-105.

- Orley J, Saxena S, Herrman H. Quality of life and mental illness. Reflections from the perspective of the WHOQOL. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172:291-3.