East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2014;24:16-22

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Ms Murugiah Shobana, International Medical University, Bukit Jalil, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Mr Coumaravelou Saravanan, International Medical University, Bukit Jalil, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Address for correspondence: Mr Coumaravelou Saravanan, International Medical University, No. 126, Jalan Jalil Perkasa 19, Bukit Jalil, 57000 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Tel: (60-3) 8656 7228; Fax: (60-3) 8656 7229; Email: saravanan_c@imu.edu.my

Submitted: 23 September 2013; Accepted:12 November 2013

Abstract

Objective: Parents’ positive attitudes and psychological wellbeing play an important role in the development of the children with developmental disability. This study aimed to measure the prevalence of psychological problems among mothers of children with autism disorder, intellectual disability, and Down syndrome. The second aim was to assess the differences in mothers’ attitudes and psychological problems among their children with intellectual disability, autism disorder, and Down syndrome. The third aim was to identify whether negative attitude was a predictor of psychological problems in these mothers.

Methods: In this study, 112 mothers of children having mild and moderate levels of autism disorder, Down syndrome, and intellectual disability were assessed using the Parental Attitude Scale and General Health Questionnaire–28.

Results: Overall, mothers of children with intellectual disability were found to have the most negative attitude towards their child. Mothers of children with autism disorder exhibited higher scores on somatic symptoms, anxiety, and social dysfunction when compared with their counterparts with Down syndrome and intellectual disability. Negative attitude was a significant predictor of psychological problems. Conclusion: Parental attitudes and psychological problems would vary among mothers of children with different types of developmental disability.

Key words: Autistic disorder; Down syndrome; Intellectual disability; Mothers

摘要

目的:父母的正向态度和心理幸福感对有发育障碍儿童的发展发挥重要作用。本研究旨在检视自闭症儿童、智障儿童,以及唐氏综合症儿童的母亲其心理问题的现患率。本研究也比较这叁类病童母亲其态度和心理问题的差异,以及确定消极态度是否母亲导致心理问题的预测因子。

方法:使用父母态度评定量表和一般健康问卷28题版,对112名轻中度自闭症儿童、智障儿童,以及唐氏综合症儿童的母亲进行评估。

结果:总体而言,智障儿童的母亲对孩子采取较为严重的消极态度。相对唐氏综合症和智障儿童的母亲,自闭症儿童的母亲於躯体症状、焦虑、社会功能障碍的得分较高。消极态度是心理问题的显著预测因子。

结论:父母态度和心理问题会根据孩子发育障碍的类别而有所不同。

关键词:自闭症、唐氏综合徵、智力障碍、母亲

Introduction

Parenting a child with developmental disability (DD) is an eternal process that affects parents and other family members.1,2 Although there is no denying the significant roles of both parents in raising a child with DD, mothers are more responsible for the caring, rearing, and education of children with DD than fathers, especially in Asian countries.3,4 Mothers are also significantly more aware of educational, therapeutic, and specialised health care services available for the child with DD than fathers; their more frequent use of such services for the child was reported.5 Hence, it can be said that mothers are the main caregivers for children with DD.6 Mothers of children with DD were reported to have lower family functioning, a higher caregiver burden, and a lower sense of coherence when compared with mothers of children with normal development.7

This study focused on 3 major DDs including autism disorder (AD), Down syndrome (DS), and intellectual disability (ID) as the prevalence of these disabilities is high in Malaysia and there is a need to focus on the mothers’ attitude and psychological problems. Autism disorders are defined as a pervasive developmental disorder which is categorised by abnormal development in social interactions, impairment in communication, as well as restricted, repetitive behaviour in certain interests and activities.8 The prevalence of AD in Malaysia is 1 in 625 children.9 Intellectual disability is a lifelong condition characterised by significant impairment in cognitive and adaptive development due to abnormalities in the brain structure or function.10 According to Amar,11 the prevalence of ID ranges from 10 to 30 per 1000 births in Malaysia. Down syndrome is a congenital condition resulting from the abnormality of chromosome 21 and is characterised by low level of intelligence quotient (IQ), a deficit in language abilities, and impairment in visual- spatial capacities.12,13 The prevalence of DS in Malaysia is recorded to be 1 in 959 births.14

Mother’s attitude plays an important role in the nurturing of children with DD. Mothers may adopt a variety of negative attitudes towards their children, such as rejection, overprotection, pessimism about future, and irrational belief in their child’s disability. In addition, mothers most likely have negative attitudes towards home management skills and educational development of their children.15-17 All these negative attitudes may lead to their adoption of maladaptive coping skills including hostility, aggression, and avoidance. One study18 revealed that mothers of children with AD scored lower on positive perceptions of their children and higher on stress levels than their counterparts with DS, and that the latter had a greater life satisfaction and positive affectivity when compared with mothers of children with ID. This is further supported by a Swedish study19 which showed that mothers of children with ID viewed their children’s condition in a negative manner when compared with normally developing children. In India, mothers of children with ID have a more negative attitude towards the child due to the lack of information and awareness regarding the child’s disability when compared with their counterparts with DS; the latter were found to show a range of attitudes from being very lenient and over-indulging to complete neglect and hostility.20,21 Previous studies22,23 have measured various negative attitudes such as overprotection, lack of acceptance, rejection, permissiveness, domination, and hostility towards children with ID; however, studies to compare the differences in the negative attitudes among the mothers of children with ID, AD, and DS are lacking.

Sound mental health of the mother is imperative for her own life and also for that of her child. Previous studies1,24 found that mothers of children with DD are prone to physical and psychological problems. Sanders and Morgan25 showed that parents of children with AD experience higher level of psychological distress compared with those of normally developing children. Furthermore, mothers of children with AD reported experience of low parenting competence, less marital satisfaction, inadequate family adaptability, and significant levels of chronic stress and fatigue.1,25 Mothers of children with DS, on the other hand, were found to exhibit higher level of psychological wellbeing than their counterparts with AD.26 However, compared with normally developing children, mothers of children with DS experienced higher level of parenting stress.12 In a study by Griffith et al,18 mothers of children with AD scored the highest for maternal stress compared with their counterparts with ID and DS, while mothers of children with DS reported having less anxiety and depression level than those of children with ID. Similarly, Eisenhower et al27 reported that mothers of children with AD ranked the highest in experiencing negative impact and maternal depression and the lowest in experiencing positive impact versus their counterparts with DS who experienced lower rates of maternal depression. In Australia, mothers of children with AD were reported to have a high rate of mental health–related problems.28 As nurturing a child with ID is lifelong and time-consuming, the mothers reported that they were emotionally and physically exhausted, and felt socially isolated.29 These findings are supported by previous researches30,31 which show that mothers of children with ID experienced considerable stress, depression, anger, shocks, denial, self-blame, guilt, and confusion. In contrast, it was observed that levels of positive mental health are similar among mothers of children with ID and without ID and autism spectrum disorder.32 Some studies in western countries have compared psychological problems between mothers of children with ID, DS, and AD. Such studies, however, have not been performed in Malaysia and South- East Asian countries.

There is a correlation between mothers’ attitudes and their psychological wellbeing.32 Parents who experience psychological problems are more likely to exhibit hostility and rejection towards their children with DD.20,21 Furthermore, psychological problems may aggravate the negative attitudes of parents. Parents have negative perceptions about and negative attitude towards their children because they believe their children will not be able to help them when they grow old. Parents of children with DD need to take care of them throughout their life and regard them as a burden for the family.20,21 These negative attitudes are the most likely causes for psychological problems in parents of children with DD. According to previous studies,32,33 parents who adopt a positive attitude and accept their children with AD exhibited a lower level of stress than those exhibited a negative attitude and lack of acceptance.32,33 Mothers who have negative attitudes are more likely to be withdrawn from society and experience marital dissatisfaction. Griffith et al18 found that parents’ positive perception was predicted by levels of maternal depression among parents of children with AD but they did not identify negative attitude as the predictor of psychological problem.

Based upon previous studies, it is well documented that differences exist in terms of attitude and psychological problems among mothers of children with AD, ID, and DS. However, none of the studies compared these 3 groups of DD in Malaysia. Hence, our study aimed to: (1) measure the prevalence of psychological problems among mothers of children with AD, ID, and DS; (2) investigate the differences in the attitude and psychological problems among these 3 groups of DD; and (3) identify whether negative attitude was a predictor of psychological problems among these 3 groups of DD. We hypothesised that there were significant differences in the attitudes and psychological problems among mothers of children with ID, AD, and DS. Another hypothesis was that the negative attitude of mothers was a significant predictor of their psychological problems.

Methods

Participants

A total of 112 mothers with children aged < 9 years and diagnosed with mild and moderate levels of ID, AD, and DS were approached in 2 special needs schools in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia for participating in this study. Of these, 7 mothers were excluded as they did not fulfil the inclusion criterion and 5 were unwilling to participate due to lack of time. Thus, 100 mothers of children with AD (n = 34), DS (n = 32), and ID (n = 34) were included in this study. Mothers who participated were living with their husbands and were educated up to undergraduate level. Mothers who were unwilling to participate and those with children having severe disabilities were excluded. The severity of disability was assigned after reviewing the case records developed by mental health professionals in the respective special needs schools. Children with severe disabilities were identified from their case records which provided clinical impressions after assessment by mental health professionals. Children with AD, ID, and DS were categorised based upon the diagnosis made by mental health professionals in the special needs schools. As such, children were considered to have mild ID provided that their IQ ranged from 50 to 70 and moderate ID with IQ ranging from 35 to 49. Children with severe and profound ID were excluded from this study as they might exhibit behavioural and organic problems. Similarly, children with mild and moderate AD and DS were categorised based upon their psychological assessment and clinical features. However, as there were some overlaps among these disorders, the researchers of this study categorised children as having AD and DS according to their clinical features and they had an IQ of above 70. All data were collected from the children’s case records. In addition, the researchers interviewed mothers to ensure that the diagnoses in case records aligned with the DSM-IV criteria for ID, AD, and DS.

Instruments and Materials

Demographic Questionnaire

A simple demographic questionnaire (DQ) was prepared for this study to collect information about the mothers’ age, education and occupation, as well as their children’s disability.

Parental Attitude Scale

Parental Attitude Scale (PAS) was used to measure parental attitudes towards children.22 The scale consisted of 40 items and was divided into 8 subscales including overprotection, acceptance, rejection, permissiveness, domination, education, home management, and hostility. The options for answer included ‘Yes’, ‘Cannot say’, or ‘No’. The ‘Yes’ (negative attitude) was given a score of 2, ‘Cannot say’ 1, and ‘No’ (positive attitude) 0. The reverse scoring subscales were acceptance, permissiveness, and education. The score ranged from 0 to 80, and a score of ≥ 40 was considered to denote significant negative attitude. The higher the overall score, the more negative the attitude. The alpha reliability of this scale was 0.86 and the test-retest reliability was 0.91 to 0.94 for the subscales.22 The alpha value of the scale in this study was 0.92.

General Health Questionnaire–28

The General Health Questionnaire–28 (GHQ-28) was used to measure the psychological problems of mothers.15 The questionnaire contained 4 subscales namely somatic symptoms, anxiety / insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression. The items were answered with 4 responses, namely, ‘not at all’, ‘no more than usual’, ‘rather more than usual’, and ‘much more than usual’. The GHQ-28 is scored from 0 to 3 for each response with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 84. A total score of 23/24 is a threshold for the presence of psychological problems. The GHQ-28 had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.77-0.93).15 The alpha value of this scale in this study was 0.91.

Procedure

After obtaining permission from the International Medical University Ethics and Research Committee to conduct this study in Malaysia, the researchers approached 2 special needs schools in Malaysia that cater to the needs of special children including those with AD, DS, and ID. The mothers of these children were approached to participate in this study when they came to pick or drop their children at the school. These mothers were explained about the aims and outcomes of this study, and reassured that withdrawal in the middle of the assessment or unwillingness to participate would not impact the status of their children in the special needs school. Mothers were also informed that all information collected from them would remain confidential. After obtaining written consent, the DQ, PAS, and GHQ-28 were administered to the mothers of children with AD, ID, and DS.

Results

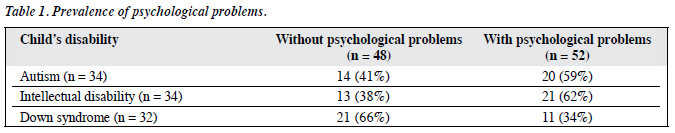

Descriptive statistics of frequency were used to determine the prevalence of parental attitude and psychological problems among the mothers. Overall, 52% of the mothers of children with DD experienced psychological problems. Mothers of children with ID exhibited the highest prevalence of psychological problems (62%) when compared with their counterparts with AD (59%) and DS (34%) [Table 1].

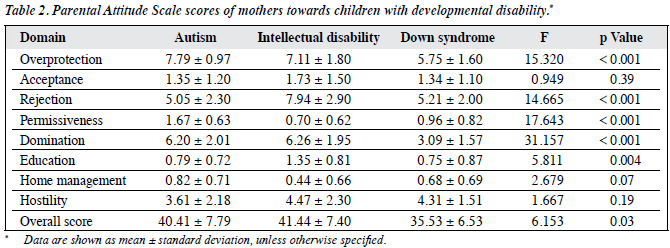

The first hypothesis was tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to analyse the differences in parental attitudes among the mothers of children with DD. The overall score of mothers’ attitudes differed significantly across the 3 DDs (F[2,97] = 6.153; p = 0.03). Significant differences were found among the mothers in the subscales of PAS including overprotection, rejection, permissiveness, domination, and education. No significant differences were found in the subscales of acceptance, home management, and hostility. A post-hoc comparison was done using the Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) for the total score of PAS. Mothers of children with AD exhibited higher negative attitude (mean ± standard deviation score, 40.41 ± 7.79) compared with their counterparts with DS (35.53 ± 6.53; p = 0.02). Furthermore, mothers of children with ID exhibited higher negative attitude score (41.44 ± 7.40) compared with their counterparts with DS (p = 0.004). However, no significant difference was found between the attitudes of mothers of children with AD and ID (Table 2).

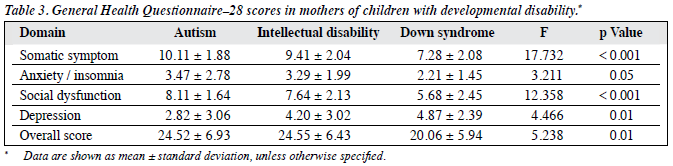

The second hypothesis was tested using one-way ANOVA to analyse the differences in psychological problems among mothers of children with DD. Psychological problems of mothers differed significantly across the 3 DDs (F[2,97] = 5.238; p = 0.01). Significant differences were found between the groups for all the 4 subscales. Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey’s HSD were performed on the overall score of GHQ-28. The mean overall score for mothers of children with AD (24.52 ± 6.93) was significantly higher than their counterparts with DS (20.06 ± 5.94; p = 0.02). The mean score of mothers of children with ID (24.55 ± 6.43) was also significantly different from their counterparts with DS (p = 0.02). However, no significant difference was noted in psychological problems between the mothers of children with AD and ID (Table 3).

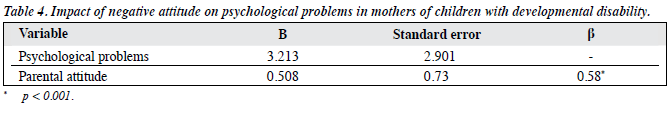

For the regression model, this study used the total parental attitude score as predictor variable and total psychological problem score as criterion variable. It was observed that negative attitude was a significant predictor of psychological problems (β = 0.58; p < 0.001) and 33% (R2 = 0.33, F[1,98] = 48.80; p < 0.001) of psychological problems could be attributed to negative attitude (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study investigated the differences in the parental attitudes and psychological problems between mothers with different types of DD. The overall prevalence of psychological problems among mothers was 52%. This finding is consistent with a meta-analysis of 18 comparative studies on maternal depression between mothers of children with and without DD, which found that 23.6% of the mothers of children with DD experienced maternal depresison.34 In addition, 40% of parents of children with DD experienced parental stress in Canada.35 In this study, the prevalence of psychological problems among mothers of children with ID was higher (62%) than their counterparts with DS and AD. The prevalence of depression among caregivers of children with ID was demonstrated as 26% in Thailand, 44% in Sweden, and 79% in Kenya; the prevalence of psychological distress among caregivers of children with ID was 47% in the US.16,24-36 These previous findings are consistent with ours that mothers of children with ID experienced higher level of psychological problems compared with their counterparts with AD and DS. However, the prevalence of depression among mothers of children with AD is higher (50%) than their counterparts with ID (44%) in Sweden.24

In Qatar, the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among mothers of children with AD was reported as 41.2% compared with 31% in mothers of children with DS.37 A strong social support system can improve maternal mental health.28 Overall, mothers of children with ID and AD were experiencing more psychological problems compared with mothers of children with DS. These mothers were psychologically more distressed as they were the primary caregivers of their children and, in effect, had less time for themselves as most of their time was spent in fulfilling their children’s demands. Cultural and social stigma were also likely causes of isolation and withdrawal from society and social gathering. They may want to avoid the embarrassment at social gatherings where people ask about the children’s disability and also fear that these people may not interact appropriately with their children.38,39

In this study, it was found that attitudes differed in terms of showing overprotection, rejection, permissiveness, and domination among the mothers of children with AD, ID and DS. Table 2 shows that mothers of children with AD in this study exhibited more overprotection and high permissiveness towards their children. These may be reactions of mothers to the significantly lower intellectual capacity and inadequate social competence of these children versus other children. However, these attitudes and approaches are more likely to increase the children’s adamant behaviour.18 Of note, some mothers of children with ID also tend to exhibit high hostility towards the children.30 However, in this study, there were no significant differences in hostility among mothers of children with any of the DDs.

The post-hoc test showed that both mothers of children with AD and ID exhibited more negative attitudes compared with mothers of children with DS. Similar findings were noted in some other studies.20,37 The mothers of children with ID exhibited more negative attitudes as their children exhibited more maladaptive behaviour compared with those with DS.20 Mothers of children with ID tend to reject their children, show domination, and have pessimistic attitude towards their children’s education, which is in concordance with another study.23 In Asian countries, people expect their children to take care of them during old age; however, in case of children with DD, parents have to be the caregivers for the children throughout their life. This may be a burden for ageing parents and gives rise to negative attitudes.23 This scenario, however, is different from that in western countries where children are not expected to take care of ageing parents.40,41 Negative attitudes towards children with DD also arise due to social stigma and lack of knowledge about the disability itself. Parents who exhibited negative attitudes towards their children with ID were found to believe that ID was contagious, and was a consequence of sins and karma committed in the past. As a result, parents were ashamed to be seen with the children as they believed these children made no positive contributions to the parents’ lives.12

In this study, mothers of children with AD experienced higher level of somatic symptoms, anxiety / insomnia, and social dysfunction compared with their counterparts with DS and ID (Table 3). Similar findings have been observed in numerous studies.18-24 The stress seems to arise from taking care of the children, comparing their children’s inability with that of normally developing children, and negative perception about the children’s future life.25-39

This study found that mothers of children with ID experienced more psychological problems compared with mothers of children with DS, whereas the mothers of children with DS experienced fewer psychological problems compared with their counterparts with AD (Table 3). However, Olsson and Hwang24 found that mothers of children with ID had a lower level of depression and psychological problems versus mothers with normal children and children with AD. Other studies18-26 identified that mothers of children with DS had a lower level of anxiety and higher level of wellbeing than their counterparts with ID and AD. Similarly, in this study, mothers of children with DS scored the lowest in somatic symptoms, anxiety, and social dysfunction. However, mothers of children with DS were found to experience a higher level of stress than those of typically developing children.42 In general, it can be said that high expectations from children with DD, comparison of their children’s deficits and behaviour with normally developing children, the need to take lifelong care of their children, the notion that having a child with DD degrades their status in the society, and having the irrational belief that DD was God’s punishment for sins committed in the past are the most likely causes of significant psychological distress.21

Parents who harbour negative attitudes towards their children experience high level of psychological problems. In this study, negative attitude predicted psychological problems in mothers of children with DD. This finding is consistent with previous studies18 indicating that low level of positive perception was a predictor of maternal depression. Parents’ positive perception towards their children with DD will increase the psychological wellbeing of parents. Parental negative attitude is a causative factor for maternal psychological problems. Modifying the negative attitude through psychological interventions is likely to reduce psychological problems and enhance the psychological wellbeing of mothers of children with DD. Before providing an intervention to the parents or children, the negative attitudes of mothers should be changed; otherwise, psychological interventions may not be effective.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size for each of the DD was considerably small. This is due to the fact that there were not many children who could be classified as having DD. Secondly, due to small sample size, the results of this study may not be generalised to all mothers of children with DD. Third, fathers were not included in the study because they were harder to approach as most of them do not come to school. The fourth limitation was that children who had severe form of DD were not included in this study as they are more prone to many medical problems.

Recommendations for Future Research

Future studies can be conducted in larger sample sizes in each DD. The impact of mother’s personality type and education status on their children with DD can also be investigated. The effect of psycho-education on the negative attitude and psychological distress among mothers of children with DD can also be studied.

Conclusion

Mothers of children with AD, ID, and DS exhibited differences in terms of their attitudes and psychological problems. Negative attitude was a significant predictor of psychological problems in mothers of children with DD. The findings suggest that mothers of children with DD had significant psychological problems that might worsen due to the negative attitudes towards their children with DD. Overall findings of this study will be useful for the mothers of children with DD to recognise the impact of negative attitude on their psychological wellbeing.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by International Medical University (Funding No.: BPS I-01/10[02]2013). There is no conflict of interest among the authors to publish this research.

References

- Gupta A, Singhal N. Positive perceptions in parents of children with disabilities. Asia Pac Disabil Rehabil J 2004;15:22-35.

- Hassall R, Rose J, McDonald J. Parenting stress in mothers of children with an intellectual disability: the effects of parental cognitions in relation to child characteristics and family support. J Intellect Disabil Res 2005;49:405-18.

- Kumari V. Parental involvement and expectations in promoting social and personal skills of mentally challenged children [dissertation]. Dharwad, India: Dharwad University; 2009.

- Roach MA, Orsmond GI, Baratt MS. Mothers and fathers of children with Down syndrome: parental stress and involvement in childcare. Am J Ment Retard 1999;104:422-36.

- Bailey DB Jr, Skinner D, Rodriguez P, Gut D, Correa V. Awareness, use, and satisfaction with services for Latino parents of young children with disabilities. Except Child 1999;65:367-81.

- Guolaugsdottir S. The experience of mothers of children with autism: a hermeneutic phenomenological study [dissertation]. London, UK: The Royal College of Nursing Institute; 2002.

- Manor-Binyamini I. Mothers of children with developmental disorders in the Bedouin community in Israel: family functioning, caregiver burden, and coping abilities. J Autism Dev Disord 2010;41:610-7.

- Siklos S, Kerns KA. Assessing need for social support in parents of children with autism and Down syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 2006;36:921-33.

- Center for Disease Control. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders: autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, United States, 2006. Website: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5810a1.htm. Accessed 10 Jan 2013.

- Shea SE. Intellectual disability (mental retardation). Pediatr Rev 2012;33:110-21.

- 1 Amar HS. Meeting the needs of children with disability in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia 2008;63:1-3.

- Norizan A, Shamsuddin K. Predictors of parenting stress among Malaysian mothers of children with Down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res 2010;54:992-1003.

- Vicari S, Belluci S, Carlesimo GA. Visual and spatial long-term memory: differential pattern of impairments in Williams and Down syndromes. Dev Med Child Neurol 2005;47:305-11.

- Normastura AR, Norhayani Z, Azizah Y, Khairi M. Saliva and dental caries in Down syndrome children. Sains Malaysiana 2013;42:59-63.

- Edwardraj S, Mumtaj K, Prasad JH, Kuruvilla A, Jacob KS. Perceptions about intellectual disability: a qualitative study from Vellore, South India. J Intellect Disabil Res 2010;54:736-48.

- Mbugua MN, Kuria MW, Ndetei DM. The prevalence of depression among family caregivers of children with intellectual disability in a rural setting in Kenya. Int J Family Med 2011;2011:534513.

- Saravanan C, Rangaswamy K. Effectiveness of counselling on the attitudes of mothers towards their children with intellectual disability. Asia Pac J Counsell Psychother 2012;3:82-94.

- Griffith GM, Hastings RP, Nash S, Hill C. Using matched groups to explore child behavior problems and maternal well-being in children with Down syndrome and autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2010;40:610- 9.

- Broberg M. Expectations of and reactions to disability and normality experienced by parents of children with intellectual disability in Sweden. Child Care Hlth Dev 2011;37:410-7.

- Bhatia MS, Kabra M, Sapra S. Behavioral problems in children with Down syndrome. Indian Pediatr 2005;42:675-80.

- Lakhan R, Sharma M. A study of knowledge, attitudes and practices (kap) survey of families towards their children with intellectual disability in Barwani, India. Asia Pac Disabil Rehabil J 2010;21:102- 17.

- Rangaswamy K. Parental attitude towards mentally retarded children. Indian J Clin Psychol 1995;22:20-33.

- Hubert J. ‘My heart is always where he is’. Perspectives of mothers of young people with severe intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour living at home. Br J Learn Disabil 2011;39:216-24.

- Olsson MB, Hwang CP. Depression in mothers and fathers of children with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res 2001;45:535-43.

- Sanders JL, Morgan SB. Family stress and adjustment as perceived by parents of children with autism or Down syndrome: implications for intervention. Child Fam Behav Ther 1997;19:15-32.

- Lewis P, Abbeduto L, Murphy M, Richmond E, Giles N, Bruno L, et al. Psychological well-being of mothers of youth with fragile X syndrome: syndrome specificity and within-syndrome variability. J Intellect Disabil Res 2006;50:894-904.

- Eisenhower AS, Baker BL, Blacher J. Preschool children with intellectual disability: syndrome specificity, behaviour problems, and maternal well-being. J Intellect Disabil Res 2005;49:657-71.

- Sawyer MG, Bittman M, La Greca AM, Crettenden AD, Harchak TF, Martin J. Time demands of caring for children with autism: what are the implications for maternal mental health. J Autism Dev Disord 2010;40:620-8.

- Li-Tsang CW, Yau MK, Yuen HK. Success in parenting children with developmental disabilities: some characteristics, attitudes, and adaptive coping skills. Brit J Dev Disabil 2001;47:61-71.

- Gupta RK, Kaur H. Stress among parents of children with intellectual disability. Asia Pac Disabil Rehabil J 2010;21:118-26.

- Heiman T. Parents of children with disabilities: resilience, coping, and future expectations. J Dev Phys Disabil 2002;14:159-71.

- Mak WW, Ho AH, Law RW. Sense of coherence, parenting attitudes and stress among mothers of children with autism in Hong Kong. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2007;20:157-67.

- Sivberg B. Coping strategies and parental attitudes, a comparison of parents with children with autistic spectrum disorders and parents with non-autistic children. Int J Circumpolar Health 2002;61Suppl 2:36-50.

- Bailey DB Jr, Golden RN, Roberts J, Ford A. Maternal depression and developmental disability: research critique. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2007;13:321-9.

- Totsika V, Hastings RP, Emerson E, Lancaster GA, Berridge DM. A population-based investigation of behavioural and emotional problems and maternal mental health: associations with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010;52:91-9.

- Charnsil C, Bathia N. Prevalence of depressive disorders among caregivers of children with autism in Thailand. ASEAN J Psychiatr 2010;11:87-95.

- Al-Kuwari MG. Psychological health of mothers caring for mentally disabled children in Qatar. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2007;12:312-7.

- Bumin G, Gunal A, Tukel S. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in mothers of disabled children. SDÜ Tıp Fakültesi Dergisi 2008;15:6- 11.

- Hill F, Newmark R, Le Grange LL. Subjective perceptions of stress and coping by mothers of children with an intellectual disability: a needs assessment. Int J Spec Educ 2003;18:36-43.

- McCallion P, Janicki M, Grant-Griffin L. Exploring the impact of culture and acculturation on older families caregiving for persons with developmental disabilities. Fam Relat 1997;46:347-57.

- Webster RI, Majnemer A, Platt RW, Shevell MI. Child health and parental stress in school-age children with a preschool diagnosis of developmental delay. J Child Neurol 2008;23:32-8.

- MacInnes LK. Parenting self-efficacy and stress in mothers and fathers of children with Down syndrome [dissertation]. BC, Canada: Simon Fraser University; 2006.