East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2014;24:23-29

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Orawan Silpakit, MD, Srithanya Hospital, Nonthaburi, Thailand.

Dr Chatchawan Silpakit, PhD, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bankgok, Thailand.

Address for correspondence: Dr Chatchawan Silpakit, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Rama 6 Road, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

Tel: (66-2) 2011275; Fax: (66-2) 3547299

Email: chatchawan.sil@mahidol.ac.th

Submitted: 22 August 2013; Accepted: 18 November 2013

Abstract

Objective: To develop a scale for assessing mindfulness named Srithanya Sati Scale (SSS) in Thai context.

Methods: Fourteen items were derived with the help from meditation experts. These were then validated by 16 mental health experts followed by analysis of their psychometric properties. A total of 466 subjects were purposively sampled from various sources. The construct validity of the scale was examined by confirmatory factor analysis. The hierarchical model was applied to test whether 3-factor model of SSS could adequately explain overall mindfulness. Test-retest reliability and the internal consistency of each subscale (awareness, acceptance, and self-recollection) were analysed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Cronbach’s alpha, respectively. Srithanya Stress Test was applied to test the discriminant validity of the questionnaire. The Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale was used for testing the concurrent validity.

Results: The 11-item SSS was found to fit across groups of people with different meditation experiences. Two of the components (awareness and self-recollection) explained the overall mindfulness in beginners. The reliability and other psychometric properties of the scale were highly acceptable.

Conclusion: The SSS may be a reliable, valid, and acceptable tool for measuring mindfulness in the Thai population. Further studies are warranted in people with more experience in meditation, as well as clinical populations.

Key words: Mindfulness; Psychometrics; Thailand

摘要

目的:建立以泰语为本的正念评估量表,名为Srithanya Sati Scale(SSS)。

方法:在冥想专家的帮助下建立评估正念的14个项目,并经16名心理健康专家以心理属性的分析验證。研究纳入466名受试者。量表以验證因素分析法检视其结构效度,并以等级制度模式测试SSS叁因子模型能否充分解释整体正念。使用Pearson相关係数和信度係数分析叁个子量表

项目(意识、接受和自我回忆)的複测信度和内部一致性。研究并使用泰国心理压力评估量表测试问卷的区分效度。费城正念量表用於测试的同时效度。

结果:SSS 11项目修正版本适合不同冥想经验的群组,而其中两大项目(意识和自我回忆)能解释冥想初学者的整体正念。SSS的可靠性和其心理测量学特性也令人容易接受。

结论:SSS是可靠、準确并容易令人接受的泰国人口正念评估工具,可考虑针对有较多冥想经验甚或临床群组作进一步研究。

关键词:正念、心理测试、泰国

Introduction

The concept of mindfulness in Thailand traditionally follows the Noble Truth and the Three Characteristics of Theravada Buddhism (impermanence, suffering, and not self).1-3 There are only few studies on the application of mindfulness meditation in daily life for patients with psychiatric disorders, and none of these studies directly measures the state of mindfulness.4,5 Therefore, the association between mindfulness skills and clinical outcomes was not empirically demonstrated. To examine this, direct measure of mindfulness skills is imperative. Currently, mindfulness assessment instruments are based on western psychology and cultures.6,7 Data showed that the stability of the construct of mindfulness across cultures is inconclusive, with reported findings being in support of and against the construct. Christopher et al1 explored the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills and Mindful

Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) among Thai and American students. They concluded that there was a significant difference in the concept of mindfulness between the cultures.1 Recently, Cardaciotto et al7 developed the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS) consisting of the dimensions of awareness and acceptance. This scale has been translated into Thai (PHLMS-Th) and its psychometric properties have been tested in highly educated hospital staff. The results showed that the Thai version had similar factor loadings as the original version.8 We also found that some items of the acceptance domain of PHLMS-Th were difficult to comprehend, especially among people who had never undertaken formal learning in mindfulness. These findings suggest that a culturally specific instrument may be needed. This study aimed to validate a questionnaire measuring the state of mindfulness among people with different meditation experiences in the context of the Thai culture and concept of Satipatthana (foundations for or the presence of mindfulness in the Buddhist tradition).3,9

Methods

Two steps, namely, item generation and psychometric property study, were carried out from June to September 2012. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of Srithanya Hospital, Thailand.

Item Generation and Selection

To obtain the operational definition of mindfulness in the Thai context, we interviewed 2 psychiatrists who had experiences with mindfulness for > 5 years, as well as a meditation teacher. We concluded that mindfulness contained 3 aspects, namely awareness of body; awareness of thought and feeling; and self-recollection. Five items were derived from 3 meditation experts. Of these, 2 were on awareness of thought and 3 on self-recollection. For awareness of body and feelings, 5 items of the PHLMS-Th, indicated by the meditation teacher and having factor loading values of > 0.6 from a previous study,8 were adopted. The first draft consisted of 10 items.

Ten mental health experts with meditation experience reviewed the first draft and compared it with MAAS and PHLMS-Th. All of them agreed on the 10 items and suggested addition of items concerning body movement and body sensation. Thus, we added 4 more items on body sensation and movement. To test the face validity, the 14-item questionnaire was sent to 18 mental health experts with more than 15 years’ experience. They were invited to rate the appropriateness of each item on the 5-point Likert scale (1 = very poor to 5 = very good). Responses from 2 experts were discarded due to incompleteness. Items which were rated > 3 by at least 13 of 16 experts were retained. No item was discarded by this criterion. The final version was named Srithanya Sati Scale (SSS) consisting of 3 subscales, namely awareness (SSS_aw) [items 1-6], acceptance (SSS_ac) [items 7-9], and self-recollection (SSS_se) [items 10-14].

Sample

A total of 466 from 500 copies of questionnaires were collected. Among these, 192 were participants of a mindfulness course (PT group), 175 were medical students (ST group), 48 hospital staff, 29 Buddhist monks, and 22 medical staff. A 5-day meditation course was held by The Young Buddhists Association of Thailand for beginners to practise mindfulness in daily life and for teaching formal meditation techniques such as walking and sitting meditation. The ST group comprised third-year medical students who attended 2-hour lecture on mindfulness delivered by one of the authors.

Test-retest Reliability

Another group of hospital staff (n = 30) was invited to complete the questionnaire twice, one week apart. Most participants (n = 24) were female and had a bachelor degree (n = 17). Their mean ± standard deviation age was 41.3 ± 11.4 years. None of them had attended any mindfulness course.

Instruments

The PHLMS-Th,8 a 5-point Likert 20-item questionnaire consisting of 2 factors, namely, awareness (PHLMS_aw) and acceptance (PHLMS_ac), was used for the concurrent validity test.

Srithanya Stress Test (ST5),10,11 a 5-item 4-point Likert scale, was used for stress assessment. Stress is one of the negative psychological symptoms which can be used to examine the discriminant validity of the questionnaire. The total score of ST5 classified the level of stress into 4 groups, including no stress (scored 0-4), mild stress (scored 5-7), moderate stress (scored 8-9), and severe stress (scored ≥ 10).12

Statistical Analysis

Demographic data were summarised with descriptive statistical analysis. Twelve incomplete questionnaire responses were excluded from further analyses. Principal component analysis (PCA) with promax was used to determine item retention in the whole sample (n = 454), PT (n = 181), and ST (n = 174) groups. The scree test was used for determining the number of components.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted in 3 steps: (1) 1-factor model; (2) 3-factor model derived from expert opinion (model a); and (3) 3-factor model derived from PCA in the PT group (model b). The hierarchical model was used in PT group to test whether 3 factors could explain the overall mindfulness. The stability of the structure of SSS across 2 groups (PT and ST) was also investigated. Comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and Chi-square (χ2) were used as fit indices through maximum likelihood estimation. Acceptable model fit was defined by the following criteria: RMSEA ≤ 0.05, CFI ≥ 0.95, and the relative χ2 (χ2/df) ≤ 3.13,14

Cronbach’s alpha was used for testing the reliability of the scale, i.e. the internal consistency of each part of SSS. Test-retest reliability was confirmed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the subscale scores of the SSS and that of ST5 was also calculated for testing the discriminant validity of the questionnaire.

To evaluate the discriminating power of the study, we hypothesised that subjects with different experiences in meditation practices and different levels of psychological stress would have different scores of mindfulness. To test this, we categorised subjects into 4 groups according to the frequency of meditation practices (regular, often, sometimes, and seldom) and the mean score of ST5, and used one-way analysis of variance to test the difference between the mean mindfulness scores among these groups.

Results

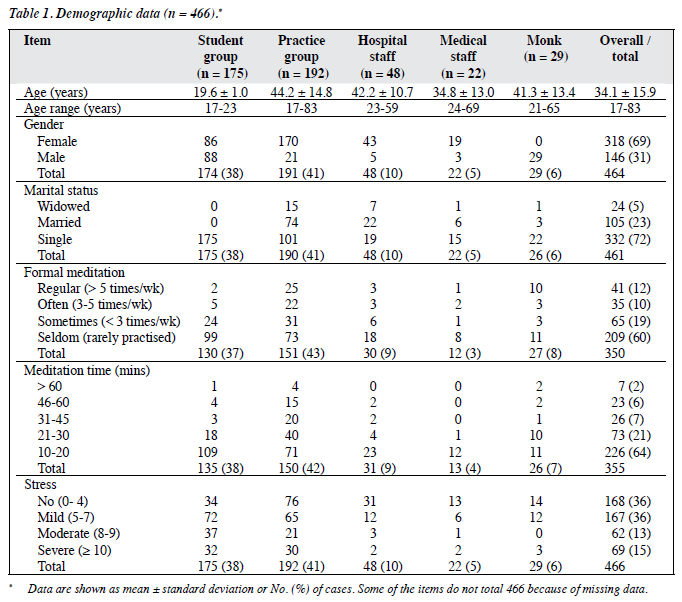

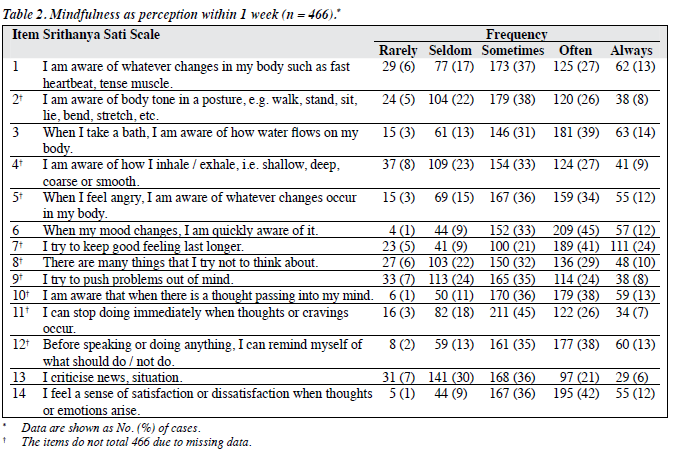

The study included a total of 466 participants. Overall, 318 (69%) were female and 332 (72%) were single. Of 350 participants who had formal meditation practice, 41 (12%) practised meditation on a regular basis. Most participants (n = 226; 64%) practised meditation for 10 to 20 minutes (Table 1). Of the 14 items of SSS, the frequency of items 6 and 14 were predominantly rated as often or always (57% and 54%, respectively) [Table 2].

Principal Component Analysis

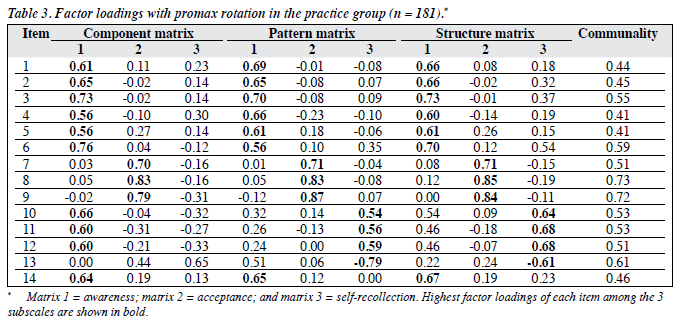

There were 454 questionnaires eligible for this part of analysis. Initially, PCA yielded 5 factors with eigenvalues of > 1.0, which accounted for 66.8% of the total variance. However, the scree plot clearly suggested a 3-factor solution. For the whole sample (n = 454), PT group (n = 181), and ST group (n = 174), the awareness factor (SSS_aw) was more important than the other 2 factors (i.e. acceptance and self-recollection) according to variance percentage. These 3 factors explained the variance for all items for the whole population, as well as the PT and ST groups at 52.8%, 53.2% and 53.2%, respectively. Regarding PT group, items 1-6 and 14 were loaded on SSS_aw, items 7-9 on SSS_ac, and items 10-13 on SSS_se. Factor loadings of all 14 items derived by exploratory factor analysis were > 0.50 (Table 3).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

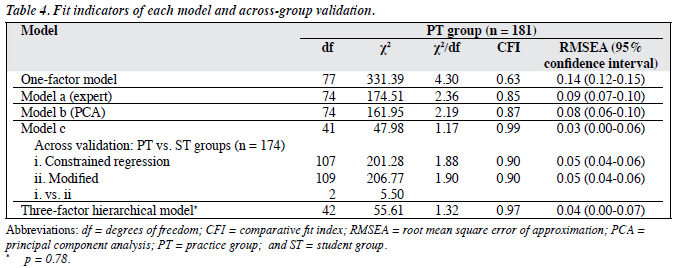

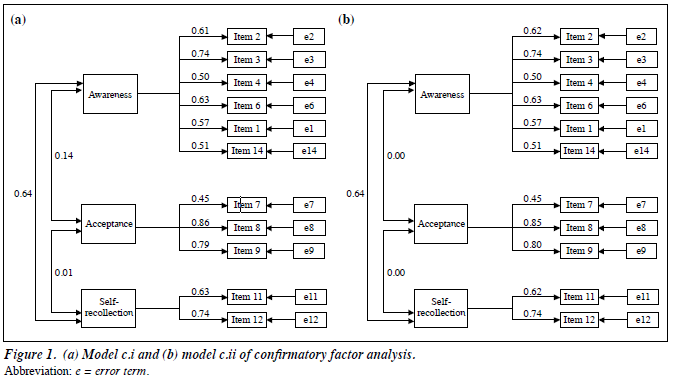

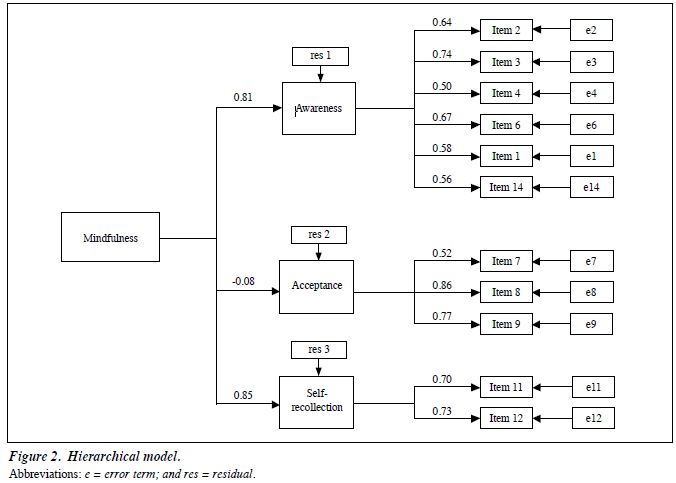

The results of CFA are displayed in Table 4 and Figures 1 to 2. The 3 proposed models, i.e. 1-factor model, model a, and model b were not fit as their fit indices did not meet the criteria (CFI < 0.95 and RMSEA > 0.05). Modification index was used to adjust model b to become model c by discarding 3 items (items 5, 10, and 13). Model c fit well in the PT group when 3 factors were allowed to intercorrelate.

To test the stability of model c among groups with different meditation experiences, it was simultaneously validated across PT and ST groups with constrained regression and correlation (i.e. factor loading and intercorrelation values were fixed) [model c.i]. A modest level of fit was indicated in model c.i as 2 of the fit criteria were met (χ2/df = 1.88; RMSEA = 0.05). When only the intercorrelation between SSS_aw and SSS_se was allowed (model c.ii), the model was also at a modest level of fit (χ2/df = 1.90; RMSEA = 0.05) but it was not significantly different from model c.i (χ2 = 5.50; df = 2; p = 0.64).

The hierarchical 3-factor model showed a good fit (χ2/df = 1.32, CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.04), suggesting that the 3 subscales of SSS could explain overall mindfulness. Although the SSS_ac was not significantly loaded on overall mindfulness, it could not be excluded from the model due to unacceptable 2-factor model.

Reliability

The 11-item SSS (model c) was further analysed for reliability and validity test. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r = 0.79) for test-retest reliability was examined in another group of hospital staff. Items 1-4, 6, and 14 were classified into SSS_aw items, items 7-9 as SSS_ac items, and items 11 and 12 as SSS_se items. Their respective alpha values were 0.77, 0.73, and 0.63 for the whole sample.

Validity

Concurrent Validity

Pearson’s correlation coefficients for PHLMS_aw and SSS_aw, and PHLMS_ac and SSS_ac were 0.70 and 0.71, respectively. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient for SSS_aw and SSS_ac was 0.15.

Discriminant Validity

The SSS had negative correlation with ST5; the Pearson’s correlation coefficients for SSS_aw, SSS_ac, and SSS_se were -0.10, -0.32, and -0.25, respectively (p < 0.05).

Discriminating Power Study

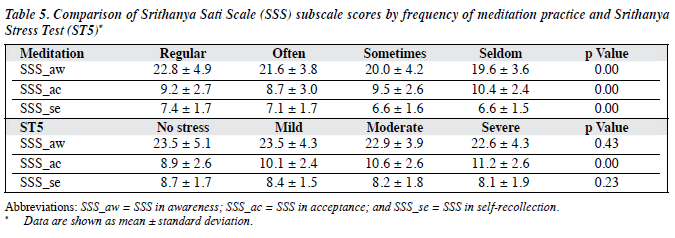

The mean scores of SSS_aw and SSS_se tended to increase with frequency of meditation practice. There were significant differences between the mean scores of SSS_aw and SSS_se among subjects in the regular-practice group and those in the seldom-practice group. The mean score of SSS_ac in the often-practice group was statistically different from that of the seldom-practice group.

Mean scores of SSS_aw and SSS_se tended to decrease with severity of stress but no statistically significant difference was noted among the 4 groups. The mean score of SSS_ ac in the non-stress group was significantly different from that of other 3 groups (Table 5).

Discussion

The sample sizes of PT and ST groups were considered adequate for analysis according to high communality.15,16 The 14-item SSS was acceptable according to expert opinion (model a) and by exploratory factor analysis (Table 3). However, by CFA, model b (from PCA) was a fair fit in the PT group. Thus, by modification index study, 3 items (items 5, 10, and 13) were discarded. Items 5 and 13 assessed advance stage of meditation practice, and item 10 was similar to item 14. Each item of SSS_se (items 10-14) and item 5 might show different loading patterns in people who had different experience with meditation, as reported by Baer et al.6

The 11-item SSS (model c) was confirmed to measure overall mindfulness. The items of SSS_aw and SSS_se subscales showed highly significant loadings but SSS_ac subscale was found to be negatively correlated with overall mindfulness. This finding might explain that the acceptance part of mindfulness needs more clarification in non-meditators. In other words, acceptance needs more meditation practice to understand the Three Characteristics of Theravada Buddhism.2,3,17

The SSS_aw and SSS_se factors could be examined independently from SSS_ac as confirmed by model c.ii; the former were modestly intercorrelated in this sample. Self- awareness is the key process for enhancing the ability to regulate an individual’s behaviour.18

It was found that people with more stress had high score of SSS_ac, a finding similar to that noted in the study by Cardaciotto et al.7 The SSS_aw factor was not correlated with the stress level. This finding was similar to that in the study by Baer et al19 which found that the observed scores were not related to the Global Severity Index in non- meditators.

Limitations

This study was carried out in a non-clinical sample and most subjects had rarely practised meditation. Self-report might overestimate mindfulness level. In the meditation group, participants were taught to notice thought and emotion; therefore, further studies in clinical samples, people who practise regularly or in those who practise different meditation techniques such as body movement or perception (vedanā) might yield different results.

Conclusion

The 11-item SSS, which consisted of 3 components including awareness, acceptance, and self-recollection, showed acceptable psychometric parameters in a population with no meditation experience, and beginners. The concurrent validity was highly acceptable with PHLMS. Further studies in clinical cases and people with experience in meditation are suggested.

Declaration

Authors declared no conflict of interest in this manuscript.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by Department of Mental Health fund. Special thanks to Mrs Rossukon Chomchuen for data collection.

References

- Christopher MS, Charoensuk S, Gilbert BD, Neary TJ, Pearce KL. Mindfulness in Thailand and the United States: a case of apples versus oranges? J Clin Psychol 2009;65:590-612.

- Mikulas WL. Mindfulness: significant common confusions. Mindfulness 2011;2:1-7.

- Payutto PP. Buddhadhamma: natural laws and values for life (Olson GA, trans). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1995: 262-9.

- Kitsumban V, Thapinta D, Sirindharo PB, Anders RL. Effect of cognitive mindfulness practice program on depression among elderly Thai women. Thai J Nurs Res 2010;13:95-108.

- Losatiankij P, Teangtum S, Punchote K. The effect of mindfulness on stress, happiness and its usage in daily living. J Ment Health Thailand 2012;14:199-206.

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, et al. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment 2008;15:329-42.

- Cardaciotto L, Herbert JD, Forman EM, Moitra E, Farrow V. The assessment of present-moment awareness and acceptance: the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment 2008;15:204-23.

- Silpakit C, Silpakit O, Wisajun P. The validity of Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale Thai version. J Ment Health Thailand 2011;19:140-7.

- The Sangha. Questions and answers. In: The teachings of Ajahn Chah: a collection of Ajahn Chah’s translated Dhamma talks. Ubon Rachathani: Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc.; 2004: 72-81.

- Silpakit C, Silpakit O, Komoltri J, Chomchuen S. Validation of the Srithanya stress scale in adolescents. J Ment Health Thailand 2010;18:24-35.

- 1 Silpakit O. Srithanya stress scale. J Ment Health Thailand 2008;16:177- 85.

- Department of Mental Health, Thailand. Srithanya Stress Test (ST5). Website: http://www.dmh.go.th/test/qtest5. Accessed 1 Jan 2011.

- Moss S. Fit indices for structural equation modeling. Website: http:// www.psych-it.com.au/Psychlopedia/article.asp?id=277. Accessed 15 Dec 2011.

- Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M. Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. J Business Res Meth 2008;6:53- 60.

- MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Preacher KJ, Hong S. Sample size in factor analysis: the role of model error. Multivariate Behav Res 2001;36:611-37.

- Maxwell SE, Kelley K, Rausch JR. Sample size planning for statistical power and accuracy in parameter estimation. Annu Rev Psychol 2008;59:537-63.

- The Sangha. Fragment a teaching. In: The teachings of Ajahn Chah: a collection of Ajahn Chah’s translated Dhamma talks. Ubon Rachathani: Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc.; 2004: 23-7.

- Vago DR, Silbersweig DA. Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): a framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Front Hum Neurosci 2012;6:296.

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Allen KB. Assessment of mindfulness by self- report: the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment 2004;11:191-206.