East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2014;24:117-24

謝樹基、袁汶茵、M Suto

Prof. Samson Tse, PhD, Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Ms Yammi Man-Yan Yuen, BSocSc, MsocSc, Caritas Wellness Link Tsuen Wan, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Melinda Suto, PhD, Department of Occupational Sciences and Occupational Therapy, University of British Columbia, Canada.

Address for correspondence: Prof. Samson Tse, Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 3917 1071; Fax: (852) 2858 7604; email: samsont@hku.hk

Submitted: 4 January 2014; Accepted: 27 June 2014

Abstract

Objectives: This qualitative study explored expected possible selves and coping skills among young and middle-aged adults with bipolar disorder in Hong Kong. Disruptive or positive experiences associated with bipolar disorder can shape the development of the sense of possible selves.

Methods: Guided by narrative inquiry methodology, 14 Chinese participants (8 women; age range, 22-65 years), recruited from community mental health services and the public, were interviewed.

Results: Young participants (18-40 years) elaborated on their expected possible selves as they related to health, work, and family, whereas middle-aged participants (41-65 years) talked about independent possible selves. The participants used problem-focused, emotion-focused, and cultural coping methods to deal with their bipolar disorder and achieve their expected possible selves. Furthermore, the young participants expressed ambivalence towards self-help strategies to manage high mood episodes.

Conclusions: This study not only improves our understanding of possible selves among young and middle- aged adults with bipolar disorder, but also provides information for designing self-help interventions. Limitations of the study along with directions for future research are discussed.

Key words: Asian continental ancestry group; Bipolar disorder; Mental disorders; Qualitative research

摘要

目的:本定性研究探讨香港青年和中年躁鬱症患者的预期可能自我和应对技巧。与躁鬱症相关的破坏或正面经验可塑造可能自我意识的发展。

方法:采用敍事研究方法,由社区精神健康服务和公众纳入14名(包括8名女性,年龄介乎22-65岁)华籍患者进行访谈。

结果:年轻参与者(18-40岁)详细阐述他们的预期可能自我与健康、工作和家庭的相关性,而中年人士(41-65岁)则谈到独立的可能自我。参与者以问题聚焦、情感聚焦和文化应对的方法处理他们的躁鬱症并达到自己预期的可能自我。此外,年轻参与者对以自助策略管理高情绪发作表示矛盾。

结论:本研究不仅提昇对青年和中年躁鬱症患者的可能自我的认识,且能提供资讯以设计相关自助措施。本文也讨论研究的限制和未来研究方向。。

关键词:亚洲大陆血统群、躁鬱症、精神障碍、定性研究

Introduction

The 12-month prevalence of bipolar disorder (BD) in the United States among young (18-44 years) and middle-aged (45-64 years) adults is 1.4% and 0.4%, respectively.1 In Hong Kong, the 12-month prevalence of BD for all age-groups is between 0.5% and 1.8%, affecting between 36,000 and 129,000 persons (and their significant others).2 The number of older adults with BD is likely to rise given that there are better medical and psychosocial interventions to improve outcomes in BD such as less suicide-related mortality, and better quality of life.3 An increasing number of qualitative studies on coping with BD have concentrated on wellness management strategies among high-functioning people,4,5 issues surrounding internalised stigma,6 exploration of recovery,7,8 and facilitating hope for recovery.9 Currently, there are no published qualitative studies that compare the coping skills of young and middle-aged adults with BD. Moreover, qualitative investigations of people with BD in Asian countries are non-existent.

Disruptive or positive experiences associated with BD can shape the development of the sense of self.10,11 The concept of possible selves (PS) can be traced back to psychology and education research in the mid-1980s. Markus and Nurius12 explained, “PS represent individuals’ ideas for what they might become, what they would like to become, and what they are afraid of becoming and thus, provide a conceptual link between cognition and motivation”. Erikson13 refined the concept and added 2 defining features of PS: (1) self-narratives of one’s future; and (2) agency, which refers to PS lending power to guide one’s behaviours. In other words, PS bridge cognition and motivation. For example, individuals with BD who dream of having a “healthy self” would seek to maintain a stable lifestyle. The concept of PS consists of 3 parts: feared PS, hoped-for PS, and expected PS.12 Feared PS are what one might be afraid of becoming. Hoped-for PS refer to who a person wants to be in the future, representing the individual’s wishes and dreams. The current study focuses on expected PS because they represent what the individual may become in the future and are based on an understanding of the individual and his or her context rather than ambiguous wishful thinking. In sum, PS have the potential to improve well-being and strengthen self-improvement efforts.14-16 Possible selves concepts have been applied to explore the notion of self and coping with mental health problems such as borderline personality disorders,17 depression,18,19 Alzheimer’s disease,20-22 and lately PS among young people in Hong Kong.23 However, no published studies have applied PS concepts to explore coping with BD.

Possible selves change across the lifespan. In a seminal work by Cross and Markus,24 significant differences in PS were identified across age-groups. The 40-to-59-year-olds mentioned more health-related PS than other age-groups. Furthermore, 25-to-39-year-old respondents mentioned significantly fewer family-related PS than those in the 40-to- 59-year-old groups. Finally, older respondents desired to do what they were already doing, whereas younger participants focused on separate, distinct plans to be realised. To date, there is a paucity of research investigating PS and coping with illness among people with BD in both western and Chinese communities. In the current study, individuals with BD in early and middle adulthood were asked to share how they saw their future and how they maintained wellness and increased their potential to achieve expected PS. The potential impact of this study is that better understanding of a person’s PS can help clinicians appreciate the person’s cognition and motivation.12 For example, a person with BD who has a possible self of becoming a peer support worker would probably be motivated to enrol in a relevant training course; if the individual can think of a “healthy” possible self, he or she would be more likely to participate in a self- help programme. In the context of recovery from BD, PS are visions of the self in a future state and can shape current lifestyle choices and health-related behaviours.16

Methods

Study Design: Narrative Inquiry

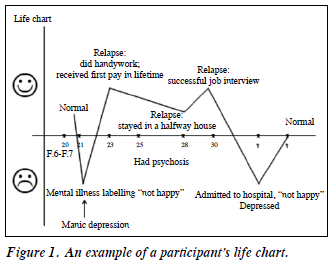

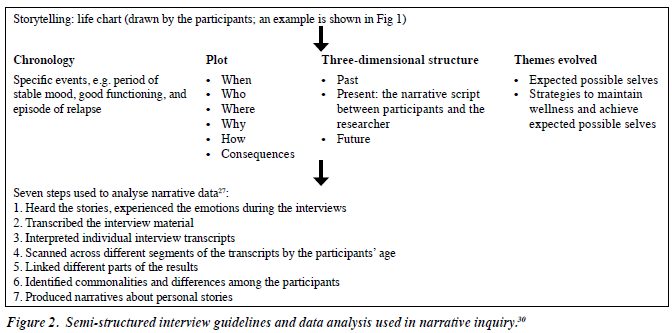

The interpretative nature of qualitative methodology offered a unique opportunity to obtain in-depth accounts of participants’ reasoning and amplify the voices of adults coping with BD in the real world.25 By engaging research participants in active and meaning-making dialogues, narrative approaches utilise personal storytelling as a legitimate way to produce knowledge.26,27 Thus, in this study, participants drew a life chart of health-related major events, the links among the events, and changes in life experiences across time at the beginning of the interview (Fig 1).

Participants

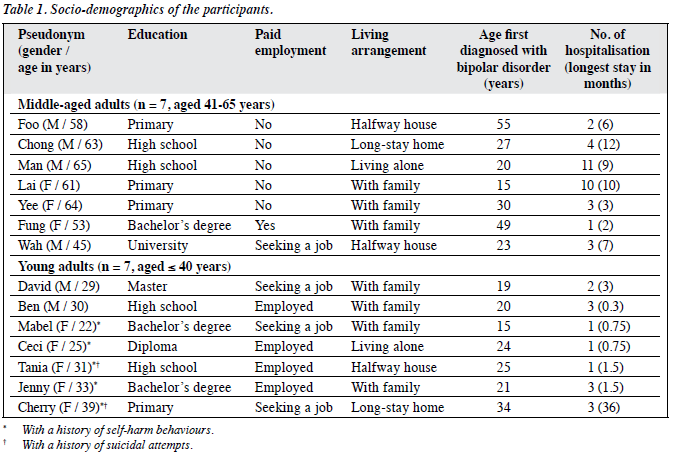

Participants were recruited from both community mental health services and the general public (through a featured item in a health column of a local Chinese newspaper in Hong Kong). To participate in the study, an individual needed to be between 18 and 65 years, be diagnosed with BD by their treating psychiatrist based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,28 and be able to reflect on their experience in relation to the topic under study. Sixteen eligible people were invited to participate in this study. Among these, 14 Chinese adults (60% women; mean [range] age, 44 [22-65] years; acceptance rate = 88%) consisting of 7 individuals in their early adulthood (age range, 18-40 years) and 7 in middle adulthood (age range, 41-65 years) participated in this study.29 The mean age when the participants were first diagnosed with BD was 26.9 years (range, 15-55 years) and they had been admitted to psychiatric facilities with a mean of 3.2 (range, 1-11) times. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic data of the participants.

Data Collection

The project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee for Non-Clinical Faculties at the University of Hong Kong (EA110410). Individual, face-to-face interviews were conducted between August 2010 and December 2012 by a research assistant and were held at a time and place generally suitable to the participants. Each session took between 60 and 90 minutes, was audio-recorded (with the participants’ written consent), and conducted in the participant’s preferred language, Cantonese. In addition to drawing a life chart at the beginning of the interview, the following topics, guided by the narrative inquiry method,30 were covered (Fig 2): (1) expected PS: “How do you see your future (not restricted to any specific time frame)?” and (2) strategies: “What do you do to keep well (probe: “to realise your future”)?” Participants were also given an opportunity to raise topics of interest to them that were not initially covered in the interview.

Data Analysis and Research Rigor

A 7-step process30 was used to analyse narrative data from the personal stories (Fig 2). Transcripts of participants’ own interviews and summaries of the researchers’ interpretation of the overall results (all in Chinese) were sent to 3 participants (out of 14 [21%] participants who agreed to check the preliminary data) to collect their feedback on the results. Only those segments to be used for this paper were translated into English. Two researchers who were bilingual checked the accuracy of the translations. To validate the researchers’ accuracy in interpreting the data,31 a summary of the findings was also presented to 2 anonymous project advisors who had personal experience of mood-related disorders. The overall findings resonated with their understanding and experience of living with BD.

Results

Theme 1: Expected Possible Selves from Early to Middle Adulthood

Expected Possible Selves and Early Adulthood

The participants in early adulthood described 3 types of expected PS. The first expected PS was about being healthy and having fewer relapses of the recurrent mood disorder. David (aged 29 years) explained, “It is important to know what triggers the symptoms and to reduce the bad effects that are brought on by the symptoms. You can reduce the number of relapses by getting support from others”. The second expected PS were related to being more successful at work. Some participants did not focus on finding a job; instead, they saw themselves furthering their studies or identifying clearer career goals. The final type of expected PS identified in this study was to become a contributing member and have harmonious relationships with family members. This is consistent with Erikson’s description of psychosocial developmental needs for intimacy in early adulthood.29 In the words of Jenny (aged 33 years), “I hope to treat my family members and friends better. I will no longer just care about myself, but also others. I want to have a better relationship with my family, so I will look after my parents and share household chores at home.”

Participants also visualised themselves caring for other family members such as children, grandmothers, and siblings with severe disability. However, after scanning his life chart, Ben (aged 30 years) shared the following insight reflecting relationships between participants and their families that have gone sour, “I find that my family experience still hurts me. They betrayed me in the past; they called the police when I did not follow their instructions”.

Expected Possible Selves and Middle Adulthood

There were 2 divergent types of responses among middle- aged adults when discussing the future. After examining her life chart, Lai (aged 61 years) described an “independent possible self”, “Leave the hostel and apply for a single unit at public housing, and be independent by myself when my mood (depression) gets better”. Wah (aged 45 years) provided a narrative account of how he might actualise his vocational aspiration or work-related PS in a step-by- step fashion, “I want to go back to the society and find a suitable job. I hope to earn money to support myself. I want to obtain public housing as soon as possible…Within half a year, I want to find a job that I am capable of doing and I am interested in. Then, I will find another job in the following half year…Working for 5 years at this job, I will tell myself that I will only work for 10 more years. I hope to have enough money to support myself and maybe my own family (if I get married) in later years. After retirement, I will do some financial investment and charity work, such as raising funds for elderly services and visiting the elderly in rest homes.”

In contrast, Chong (aged 63 years) gave a very different narration about his past and future self that showed his attempt to integrate his earlier life experience and come to terms with his basic identity, “I do not want to talk with anyone about my sadness that I have no children...I am 63 years old now. You tell me what I can do now. I can do nothing; I do not know what to say. I want to be a singer because I am good at singing. I obtained a prize in the singing and dancing competition in the long-stay care home. I want to be a great man, but now I am a failure.”

Theme 2: The Art of Coping with Bipolar Disorder and Achieving Possible Selves

Comparing Early and Middle Adulthood

Generally, middle-aged participants did not list as many coping methods as the younger participants. Another difference was in the health problems they faced. The middle-aged adults spoke of experiencing such problems as chronic pain, mild stroke, and numbness, while participants in early adulthood described problems or complications related to personality difficulties, substance abuse, post- traumatic stress, and anxiety.

Primary Control Coping

Attempts were made to reduce stress levels or seek relief from unpleasant feelings by using problem-solving or emotion-focused methods.32 These included walking frequently, gaining support from religious activities or spiritual beliefs, using problem-focused and emotion- focused problem-solving adaptively, gaining support from family (e.g. spouse, parents, or siblings), developing a list of people who can help when one becomes unwell, and blogging. Mabel (aged 22 years) explained, “Writing a blog: I typed everything that I wanted to type, for example, what happened to me, including the unhappy things; I created a story and typed it out. This method helped me using 60% of the time”. The support and services frequently described by the participants included taking medications, seeking help from mental health professionals, and accessing specific community support services such as vocational assistance.

Secondary Control Coping

Secondary control coping involves increasing the level of knowledge about the illness and engaging in cognitive restructuring, positive reappraisal, acceptance, or psychological distancing.32 The middle-aged participants described attending lectures in public libraries and reading books to learn about BD, whereas the younger participants were more inclined towards learning from the internet, studying information on medication packages, and working as volunteers in health information centre so they could access the latest information.

Cultural Coping Methods

The methods used by Chinese people to maintain health are different from those used by western people.33 Chinese people consider health to be related to one’s harmoniousness, which can be influenced by one’s state of mind as well as the external environment and social conditions. Wang et al33 wrote, “The social environment includes all things and events that surround an individual such as the air, plants, people, society, death, illness, and even spiritual thoughts. In order to harmonize oneself with the social environment, a person has to accept what happens in life and modify themselves to best fit in with it”.

Consistent with Chinese cultural beliefs, many participants used a variety of practices and non-western traditions. These included acupuncture, a balanced diet, tai chi, qi gong, and Chinese tea to improve their sleep and bodily vitality. Wah (aged 45 years) learned more about illness management specific to Chinese culture in order to stay well, “I went to the library and read books related to Chinese medicine, such as The Inner Canon of Huangdi [黃帝內經] and The Book of Changes [易經], and lifestyles that can keep us healthy. For example, I learnt that we have to sleep early, not work for long hours at night, and take some specially prepared soup in order to stay healthy.”

Theme 3: Putting Self-help Methods into Practice

The majority of participants gave detailed narratives on how they coped with BD. They engaged in work-related activities, meditated, listened to religious music and songs, participated in hostel activities, watched movies, smoked, and painted. However, some participants spoke of the difficulties they faced and the ambivalence they felt when putting self-help methods into practice. Narratives from 4 participants revealed several insights.

First, some participants could not identify the triggers of their relapse. “I did not know what triggered my symptoms…when I was depressed, people asked me to do something that I did not want to do and they got annoyed with me…and I was not aware of the manic period and I did not know what triggered my manic symptoms, not to mention how to cope…I had a blackout.” (David, aged 29 years). Second, BD is unusual since one can become unwell even when things are going well (e.g. receiving the first wage in one’s lifetime). “Earning my first income could trigger symptoms too...I knew I was in a manic state.” (Wah, aged 45 years). Similarly, staring at his life chart, Wah recalled how a successful job interview resulted in a relapse. Third, participants could not engage in self-help strategies when they were already unwell. Cherry (aged 39 years) put it very succinctly, “If I was in a manic state, I could not control myself.” Fourth, some young participants revealed that they actually enjoyed their high moods; thus, they were ambivalent about managing the manic phase. For example, Mabel (aged 22 years) shared candidly, “I enjoyed my manic state. I was confident. I would not find ways to manage my manic state because I would not hurt myself.”

Discussion

Expected Possible Selves

The present findings identified 3 features of positive PS for both young and middle-aged participants: expectations of health, paid employment, and better relationships with their families. Young participants were hopeful about their future, which is unsurprising given their young ages. However, previous studies34 have shown that a sense of hope alone does not result in goal attainment. This group may benefit from individualised solution-focused interventions such as interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, and cognitive behavioural therapy to obtain improved family relationships.35 Furthermore, educating employers about BD and requesting workplace accommodations may turn individual hopes into reality.36

Also, consistent with a similar study of middle-aged and older adults with a different condition (schizophrenia),37 the present study found that a subgroup of middle-aged participants expressed a sense of failure and despair. They tended to view themselves as “losers” who could not see much of their future or expected PS. Shepherd et al37 elaborated, “[they] despaired over lost opportunities over the lifespan, and experienced a significant discrepancy between their goals for the future and their current situation”. This group may benefit from peer support groups focusing on setting short-term goals, achieving empathetic understanding, and reducing self-blame and regret.38,39

Coping with Bipolar Disorder

The participants in this study used a variety of techniques to manage the psychosocial sequel of having BD with a varying degree of success.40-42 This might be related to the ambivalence expressed by some young participants (i.e. they enjoyed their high moods). Previous studies6,43 have reported that, during manic episodes, some individuals experience an amplification of perception, emotions, and cognitive abilities; and increased confidence in performing complex tasks and connecting with other people. Other researchers noted that participants’ ambivalence about manic states was related to the energising and positive features of elevated moods, which helped them accomplish things but also caused them some distress.8 Jamison44 echoed, “I have often asked myself whether, given a choice, I would choose to have manic depressive illness…strangely enough I think I would.” Instead of simply labelling the fact that some people with BD enjoy the manic episode as lacking insight, therapists should try to gain an in-depth and empathetic understanding of ambivalence towards treatment to strengthen the therapist-client alliance and reduce the dropout rate from clinical services.8

Middle-aged participants mentioned fewer coping skills than the younger participants. However, this finding has to be interpreted with caution. Having a narrow repertoire of coping methods does not necessarily mean middle-aged adults manage their illness less ably than their younger counterparts. Both the classic literature on positive ageing45 and a recently proposed framework of recovery for older adults46 emphasise that the process of using current and established behavioural patterns (as opposed to finding new coping methods or resources) enhances an enduring sense of identity and adjustment to individuals in middle and old adulthood.

Comparison with a Closely Relevant Study

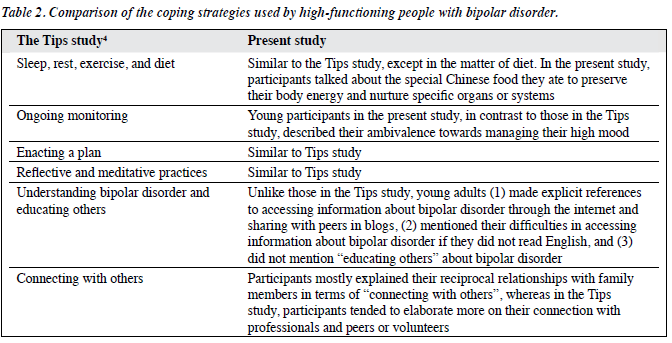

The findings of a recent qualitative study (the Tips study)4 were compared with the current findings, because the former research (32 adults living in British Columbia, Canada; mean [± standard deviation] age, 41.1 ± 13.3 years) reported a comprehensive framework of coping skills (called “self- management strategies”) employed by high-functioning individuals with BD to stay well or regain their wellness. In addition, the framework overlapped considerably with important principles in adjunctive psychotherapies. The current study’s findings support those of the Tips study (Table 2). Both studies documented how participants used a range of activities to maintain their wellness such as exercise and reflective practice. In contrast with participants in the Tips study, however, some participants in the present study learned about BD through the internet, explained their reciprocal relationships with family members in terms of “connecting with others”, and were sometimes ambivalent about managing their high moods. The tendency to seek advice about BD from family reflects the collectivistic family orientation among the Chinese participants in the present study.33,47,48 Individuals with a collectivistic value orientation tend to see themselves and their life goals as an inseparable part of a family, community, or tribe. Collectivism is a cultural value in which the extended family is the central concept, and the needs of an individual family member are subordinate to a sense of family responsibilities.49 The similarities and differences between the 2 studies have to be interpreted with caution since the present study did not solely focus on high-functioning individuals and was conducted in a different location and ethnic community when compared with the Tips study.4

Strengths and Limitations

This study addresses a gap in the literature by offering new information about how people with BD in early and middle adulthood see their future, and how they maintain wellness in a non-western context. The narrative inquiry design emphasises the stories of people living with BD rather than the researchers’ a priori assumptions and knowledge. This study had limitations; only a small sample size was used and the participants needed to be willing and able to participate in an interview that lasted at least an hour. This requirement excluded individuals who were mentally unstable, thus, restricting the applicability of the current findings to a wider clinical population.

Conclusions

As PS have been proven to be an important motivation construct, this study provides useful information on the coping strategies used by young and middle-aged Chinese adults while recovering from BD to realise their PS and move positively towards them. The findings also shed light on how brief intervention programmes for adults with BD can be designed to develop their self-management skills and foster a positive future identity.5,33 Finally, this exploratory study suggests possible directions for future research. These include comparing the recovery trajectory of individuals with and without expected PS, and studying how middle- aged and older adults with BD interpret the meaning of recovery over time. Because of the small sample size, the study did not examine differences in PS and coping methods among participants with early versus late onset of BD, which could have been a very useful investigation.1

References

- Depp CA, Jeste DV. Bipolar disorder in older adults: a critical review. Bipolar Disord 2004;6:343-67.

- Lee S, Ng KL, Tsang A. Community survey of the twelve-month prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in Hong Kong. J Affect Disord 2009;117:79-86.

- Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ. Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet 2013;381:1672-82.

- Suto M, Murray G, Hale S, Amari E, Michalak EE. What works for people with bipolar disorder? Tips from the experts. J Affect Disord 2010;124:76-84.

- Murray G, Suto M, Hole R, Hale S, Amari E, Michalak EE. Self- management strategies used by ‘high functioning’ individuals with bipolar disorder: from research to clinical practice. Clin Psychol Psychother 2011;18:95-109.

- Michalak E, Livingston JD, Hole R, Suto M, Hale S, Haddock C. ‘It’s something that I manage but it is not who I am’: reflections on internalized stigma in individuals with bipolar disorder. Chronic Illn 2011;7:209-24.

- Michalak EE, Hole R, Holmes C, Velyvis V, Austin J, Pesut B, et al. Implications for psychiatric care of the word ‘recovery’ in people with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Ann 2012;42:173-8.

- Veseth M, Binder PE, Borg M, Davidson L. Toward caring for oneself in a life of intense ups and downs: a reflexive-collaborative exploration of recovery in bipolar disorder. Qual Health Res 2012;22:119-33.

- Hobbs M, Baker M. Hope for recovery — how clinicians may facilitate this in their work. J Ment Health 2012;21:144-53.

- Davidson L, Strauss JS. Sense of self in recovery from severe mental illness. Br J Med Psychol 1992;65:131-45.

- Inder ML, Crowe MT, Moor S, Luty SE, Carter JD, Joyce PR. “I actually don’t know who I am”: the impact of bipolar disorder on the development of self. Psychiatry 2008;71:123-33.

- Markus H, Nurius P. Possible selves. Am Psychol 1986;41:954-69.

- Erikson MG. The meaning of the future: toward a more specific definition of possible selves. Rev Gen Psychol 2007;11:348-58.

- Cross SE, Markus HR. Self-schemas, possible selves, and competent performance. J Educ Psychol 1994;86:423-38.

- King LA, Hicks JA. Lost and found possible selves: goals, development, and well-being. New Dir Adult Contin Educ 2007;114:27-37.

- Oyserman D, James L. Possible selves: from content to process. In: Markman KD, Klein WM, Suhr JA, editors. Handbook of imagination and mental simulation. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2009: 373-94.

- Janis IB, Veague HB, Driver-Linn E. Possible selves and borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychol 2006;62:387-94.

- Allen LA, Woolfolk RL, Gara MA, Apter JT. Possible selves in major depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996;184:739-45.

- Penland EA, Masten WG, Zelhart P, Fournet GP, Callahan TA. Possible selves, depression and coping skills in university students. Pers Individ Dif 2000;29:963-9.

- Haley P. The relation between Alzheimer’s disease caregiving status, health-related possible selves, and health behaviors. Alabama, US: The University of Alabama; 2009.

- Frazier LD, Cotrell V, Hooker K. Possible selves and illness: a comparison of individuals with Parkinson’s disease, early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, and healthy older adults. Int J Behav Dev 2003;27:1-11.

- Cotrell V, Hooker K. Possible selves of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Aging 2005;20:285-94.

- Zhu S, Tse S, Cheung SH, Oyserman D. Will I get there? Effects of parental support on children’s possible selves. Br J Educ Psychol 2014;84:435-53.

- Cross S, Markus H. Possible selves across the life span. Hum Dev 1991;34:230-55.

- Yardley L, Bishop F. Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: a pragmatic approach. In: Willig C, Stainton-Rogers W, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications; 2008: 352-70.

- Clandinin DJ, Connelly FM. Narrative inquiry: experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2004.

- Fraser H. Doing narrative research: analysing personal stories line by line. Qual Soc Work 2004;3:179-201.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR, fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Berk LE. Development through the lifespan. 5th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2010.

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007.

- Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2009.

- Grassi-Oliveira R, Daruy-Filho L, Brietzke E. New perspectives on coping in bipolar disorder. Psychol Neurosci 2010;3:161-5.

- Wang G, Tse S, Michalak EE. Self-management techniques and New Zealand Chinese with bipolar disorder: a qualitative study. Int J Ther Rehabil 2009;16:602-8.

- Cook JA, Copeland ME, Jonikas JA, Hamilton MM, Razzano LA, Grey DD, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial of mental illness self-management using Wellness Recovery Action Planning. Schizophr Bull 2012;38:881-91.

- Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Kogan JN, Sachs GS, et al. Intensive psychosocial intervention enhances functioning in patients with bipolar depression: results from a 9-month randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1340-7.

- Montejano LB, Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ. Impact of bipolar disorder on employers. Dis Manag Health Outcomes 2005;13:267-80.

- Shepherd S, Depp CA, Harris G, Halpain M, Palinkas LA, Jeste DV. Perspectives on schizophrenia over the lifespan: a qualitative study. Schizophr Bull 2012;38:295-303.

- Davidson L, Bellamy C, Guy K, Miller R. Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry 2012;11:123-8.

- Doughty C, Tse S. The effectiveness of service user-run or service user-led mental health services for people with mental illness: a systematic literature review. Wellington: New Zealand Mental Health Commission; 2005.

- Jones S, Deville M, Mayes D, Lobban F. Self-management in bipolar disorder: the story so far. J Ment Health 2011;20:583-92.

- Tse S, Murray G, Chung KF, Davidson L, Ng KL, Yu CH. Exploring the recovery concept in bipolar disorder: a decision tree analysis of psychosocial correlates of recovery stages. Bipolar Disord 2014;16:366-77.

- Tse S, Chan S, Ng KL, Yatham LN. Meta-analysis of predictors of favorable employment outcomes among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2014;16:217-29.

- Lobban F, Taylor K, Murray C, Jones S. Bipolar disorder is a two- edged sword: a qualitative study to understand the positive edge. J Affect Disord 2012;141:204-12.

- Jamison KR. An unquiet mind. New York, NY: Crown Publishing Group / Random House; 1996.

- Atchley RC. A continuity theory of normal aging. Gerontologist 1989;29:183-90.

- Daley S, Newton D, Slade M, Murray J, Banerjee S. Development of a framework for recovery in older people with mental disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;28:522-9.

- Tse S, Cheung E, Kan A, Ng R, Yau S. Recovery in Hong Kong: service user participation in mental health services. Int Rev Psychiatry 2012;24:40-7.

- Mellor D, Carne L, Shen YC, McCabe M, Wang L. Stigma toward mental illness: a cross-cultural comparison of Taiwanese, Chinese immigrants to Australia and Anglo-Australians. J Cross Cult Psychol 2013;44:352-64.

- Tse S, Davis M, Li YB. Match or mismatch: use of the strengths model with Chinese migrants experiencing mental illness: Service user and practitioner perspectives. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2010;13:171-88.