East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:21-28

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

吴倩华、骆正昌、李紫君、吴碧琪

Dr Serena SW Ng, EdD, MSc, Occupational Therapy Department, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Mr Davis CC Lak, MPhil, Occupational Therapy Department, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Ms Sharon CK Lee, MSocSc, Occupational Therapy Department, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Ms Peggie PK Ng, MSc, Occupational Therapy Department, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Serena SW Ng, Occupational Therapy Department, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Tel: (852) 3129 6070; Fax: (852) 2624 7401; Email:ngsws@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 25 July 2014; Accepted: 3 October 2014

Abstract

Objectives: Occupational therapists play a major role in the assessment and referral of clients with severe mental illness for supported employment. Nonetheless, there is scarce literature about the content and predictive validity of the process. In addition, the criteria of successful job matching have not been analysed and job supervisors have relied on experience rather than objective standards in recruitment. This study aimed to explore the profile of successful clients working in ‘shop sales’ in a supportive environment using a neurocognitive assessment protocol, and to validate the protocol against ‘internal standards’ of the job supervisors.

Methods: This was a concurrent validation study of criterion-related scales for a single job type. The subjective ratings from the supervisors were concurrently validated against the results of neurocognitive assessment of intellectual function and work-related cognitive behaviour.

Results: A regression model was established for clients who succeeded and failed in employment using supervisor’s ratings and a cutoff value of 10.5 for the Performance Fitness Rating Scale (R2 = 0.918, F[41] = 3.794, p = 0.003). Classification And Regression Tree was also plotted to identify the profile of cases, with an overall accuracy of 0.861 (relative error, 0.26).

Conclusion: Use of both inference statistics and data mining techniques enables the decision tree of neurocognitive assessments to be more readily applied by therapists in vocational rehabilitation, and thus directly improve the efficiency and efficacy of the process.

Key words: Employment, supported; Mental disorders; Neuropsychological tests

摘要目的:职业治疗师在评估和转介精神病康复者往辅助就业方面发挥重要作用。然而,有关程序的内容和预测效度的文献报告甚少。此外,有关成功就业选配的标準还没有被分析,而工作主管往往根据招聘经验多於客观的标準对店务员作出评估。因此,本研究旨在透过神经认知评估协议,检视在具支持性的环境内从事店员而成功获聘的患者情况,并以此验證工作主管其主观标準协议。

方法:这是针对单一职业的效标关联量表同时效度研究,即把工作主管的主观评级与智力功能和与工作相关的认知行为神经认知评估结果作并行验證。

结果:根据主管评级和以表现适度量表得分为10.5作截止点,为就业成功和失败的个案建立迴归模型(R2 = 0.918,F[41] = 3.794,P = 0.003),并标划分类与迴归决策树以确定不同个案的情况;总体準确度为0.861(相对误差,0.26)。

结论:推论统计和数据探勘技术使治疗师把神经认知评估决策树能更直接应用於职业康复服务上,从而提高其效率和效能。

关键词:辅助就业、精神障碍、神经心理学测试

Introduction

Employment plays an important role in the rehabilitation of individuals with mental illness (MI). According to Scheid and Anderson,1 work is central to identity, self- esteem, and wellbeing. Work may enhance mental health by providing some form of meaningful activity and a sense of accomplishment. It is generally agreed that if an individual can work, he / she is fundamentally well. To enhance vocational outcomes of individuals with MI, a variety of vocational rehabilitation programmes have been provided such as cognitive remediation,2 social skills training,3 vocational assessment and training, individual placement, and supported employment (SE) services.4 Occupational therapists play a major role in assessment and referral for these services. Nonetheless, there is scarce literature available locally about the content and predictive validity of the process. Further, the criteria of successful job matching have not been previously analysed and job supervisors have historically relied on their experience rather than objective standards in recruitment. As a result, many trial work placements fail with a consequent reduced motivation for the client to return to work.

Literature Review

In the development of employment support for individuals with MI, employment has been identified as a key component of recovery. Those with MI who hold competitive jobs for an extended period of time frequently experience a number of benefits, including improved self-esteem and symptom control. Components of a good SE programme promote rapid job search and placement as well as a focus on competitive employment.5,6 This form of vocational rehabilitation programme for MI is now the main source of support offered by local service providers including psychiatric hospitals and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Overseas research has shown that employment rates among individuals with MI in the open competitive market range from 10% to 30%. However, only 10% to 15% of those who find work are still employed 1 to 5 years later, and up to 70% of this population remain unemployed.7 Nonetheless, the rate of employment in a local study of a major psychiatric hospital that provided a supported competitive employment programme for MI achieved a 68.8% rate of employment, which is higher than that of previous studies.8 Wong et al8 claimed there were 2 principal reasons that might account for this difference. First, they performed a separate screening interview to ensure the client had the prerequisite work potential other than just an interest to work, and second, there was an emphasis on rapid job search and placement rather than on individual preference in order to speed up development of relevant work experience and skills. The success rate was further improved in SE programmes that included social cognition training and work-related skills training.3,9

The prime clinical role of the therapist, that is, reliable screening of work potential and rapid matching with a competitive job, is based mainly on professional judgement and intuitive reasoning derived from a client’s short-term performance in therapy sessions or simulated job environment in the clinical setting.10 Objective ability testing is not a common approach among therapists to assessment for decision-making in this area of practice. Hence, sharing and standardisation of testing cannot be facilitated across the profession and outcomes of service cannot be likewise applied.

Over the last decade, local NGOs have tried hard to make available different trades in SE service in order to accommodate different levels of client functioning. Although shop sales is one of the most common trades available for placement, the demands made on the trainees are complex and multi-faceted with respect to required skills, social performance, work tolerance, and speed.10 The placement coaches utilise another approach of on- the-job assessment to determine the suitability of a client to the job and the result tends to differ to the therapist’s recommendations. Hence, a more structured assessment process carried out by the occupational therapist, that takes account of the standards and requirements of the placement supervisors, is vital to help clients make a correct choice to be in shop sales, and reduce mismatched placements.

Cognition at Work

Cognitive impairment is a hallmark of MI and may be independent of symptom severity, may predate illness onset, and is difficult to treat with neuroleptics.11 Nonetheless it does impact on vocational and social function12,13 and predict performance in work.14 Cognitive function is most often measured by neurocognitive tests administered in an office setting. The validity of the results in comparison with the applied cognitive functioning demanded by a work setting is unknown. Neurocognitive tests may not be able to measure demands that are specific to the tasks and environment of a work setting with different scenarios, including executive cognitive function, problem solving, and social cognitive function.

Hence, a correlation study to investigate the expert supervisor assessment in actual work sites and cognitive function assessment in occupational therapy (OT) department is essential and can optimise the benefit gained from an occupational therapist.

Methods

This study aimed to first validate the ‘success’ profile for clients with MI who were to be placed in SE service of a major NGO as shop sales. Second, the study developed a decision pathway in the administration of neurocognitive assessments according to the success profile identified.

This was a concurrent validation study of criterion- related scales for a single job type. It was based on an assumption that experienced job supervisors could rate the degree of success of their clients very accurately in qualitative terms after compiling all the information from the actual working environment. The job supervisor formulated an internal neurocognitive standard required by a successful trainee to be able to sustain a job as ‘shop sales’ from their daily performances in the job trial period. The intention was to develop a decision pathway that could simulate such an expert’s judgement or internal standards. The protocol so developed would provide a standardised, systematic profile against which occupational therapists could review and compare all the data gained from objective assessments performed during therapy sessions.

In this study, a group of job supervisors were asked to rate the recruited sample clients, including those who were already employed as staff, the trainee, and the failed applicants using the Vocational Cognitive Rating Scale (VCRS).15 They also completed the subjective Performance Fitness Rating Scale (PFRS), a visual analogue scale devised in this study.10 The ratings were concurrently validated against the results produced by occupational therapists who assessed the same trainees / workers in the OT department within 2 weeks using the battery of objective cognitive assessments for job matching in SE, namely intellectual function, work personality, work performance, and social skills at work.

Measurements

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST computer version) is widely acknowledged as a measure of executive function, has been shown to measure cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, and is able to discriminate among diagnostic groups.16 We used the computed data ‘T score of total errors’ to denote the learning abilities of the client.

The Stroop test is a psychological test of our mental (attentional) vitality and flexibility. The cognitive mechanism involved in this task was called ‘directed attention’.17 The Stroop test provides insight into cognitive effects that are experienced as a result of attention fatigue. The T score of interference was used in this analysis.

Contextual Memory Test18 (CMT) assesses memory capacity, strategy of use, and recall in adult clients with memory dysfunction. It is used with a variety of diagnoses, including head trauma, cerebral vascular disorders, multiple sclerosis, depression, schizophrenia, and chronic alcohol abuse. When contextual cues affect remembering, memory is said to be context-dependent. Context-dependent memory implies that when events are represented in memory, contextual information is stored along with memory targets; the context can therefore cue memories containing that contextual information. It is important to note that in this case context referred to that which surrounded a target, whether the surrounding was spatial, temporal, or meaningful in nature. Contextual memory is considered more relevant in reflecting an individual’s learning ability in a new work situation in their encoding, transferring, and processing speed.19 Neurocognitive scores for both immediate recall contextual memory and delayed recall contextual memory were used in this analysis.

Vocational Cognitive Rating Scale15 is designed to measure cognitive impairment in the workplace specifically for people with chronic mental illness. The test comprised 16 items (Box) that were rated from workplace observation and information by supervisors. Each item was a behavioural descriptor rated on a 5-point scale (1 = consistently inferior performance; 2 = occasionally inferior performance; 3 = adequate performance; 4 = occasionally superior performance; 5 = consistently superior performance). Strong predictive validity was demonstrated in terms of work hours and work performance. Item scores were used in this analysis.

Box. Items of Vocational Cognitive Rating Scale for assessment.

- Understand simple instructions without repetition

- Stay focused when performing a simple task

- Able to focus on a detailed aspect of task without needing the supervisor’s attention

- Continue to work without slowing down when he / she sees or hears something interesting or different

- Continue to work without slowing down when small parts of the job divert his / her attention

- Can remember instructions or begin tasks without a reminder

- Remember to do parts of the task that are done everyday

- Able to learn new tasks quickly

- Can complete a task with ≥ 2 parts without assistance

- Remember how to do tasks that are not performed everyday

- Smooth transitions from one task to another

- Able to efficiently organise multiple tasks

- Start tasks without prompting

- Seek new work when assigned tasks are completed

- Able to independently solve routine problems when they arise on the job

- Compensate for cognitive weakness with strategies (e.g. using written reminders) when necessary

Regarding PFRS, supervisors were asked to rate on a 20-point visual analogue scale, the higher the better, about the overall suitability of the client to shop sales. This was used as the gold standard for neurocognitive assessment of the supervisor in this analysis. Eight subscale items were selected based on a qualitative study of predictive factors for successful work placement by a group of expert occupational therapists.10 These items included personality, cognition, initiation, social skills, work attitude, work skills, adaptability, and emotion. Supervisors were briefed with a description for each subscale.

Sampling

Clients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and attended an SE unit were recruited to undergo standardised cognitive assessment by a blinded assessor in an OT unit. Their performance rating when working or training as shop sales in the SE unit was also collected from their direct supervisors at work for comparison. An overall performance rating of the most recent 2 months was considered.

A convenient sample of 57 subjects (p = 0.05, r = 0.2-0.4 for concurrent validation of dependent variables in single measure) was collected from the shop sales group in the SE service of a major NGO, and included existing workers, trainees, and failed applicants. Subjects had to be diagnosed with a mental disorder according to the DSM-IV; and be adult, either male or female; < 65 years; literate; without vision, hearing or communication deficits; and be mentally stable.

Data Collection and Analysis

Written (Chinese) informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. All participants were informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. The research was approved by the Kowloon Central Cluster Research Ethics Committee under the Hospital Authority. All neurocognitive assessments, namely the WCST, Stroop test, and CMT were performed by a trained occupational therapist blinded to the client’s performance in an existing job. The clients’ supervisor was required to rate the VCRS and was blinded to the OT assessment results. The supervisors were also asked to rate on those nine 20-point visual analogue subscales (1 overall rating and 8 subscale items), the higher the better, about the suitability of the client for shop sales. This was used as the gold standard of ‘success’ in this analysis.

All data were treated as continuous data. By using SPSS Windows version 19.0, descriptive statistics were generated to analyse the demographic and baseline data of the 3 categories of clients, namely trainee, staff, and failure groups. Spearman correlation and factor analysis were used to explore the relationship among dependent variables. Generalised Rules Induction methodology20 was employed to classify and determine the cutoff range of supervisors’ ratings for success profile. Regression analysis was then computed to explore the prediction variables against the supervisors’ rating. Using PASW Modeler 13, Classification And Regression Tree (CART),21 or a decision tree, was constructed from the validated prediction model for successful and unsuccessful clients for the target job.

Results

Client Profile

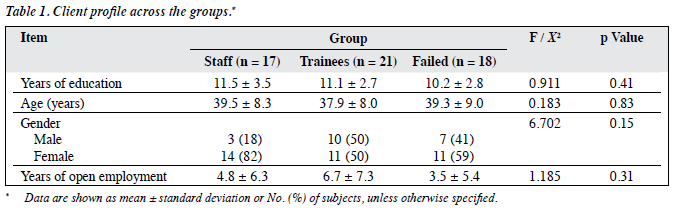

A total of 56 clients were referred from the SE unit for assessment within 2 months: 17 (30%) were staff, 21 (39%) were trainees, and 18 (32%) failed in their trial period. One client refused to join the study; 20 (35%) clients were male and aged between 19 and 53 years. Only 13 (23%) had no open employment history. There was no significant difference among these 3 groups of clients in terms of age, years of education, gender, or employment history (Table 1).

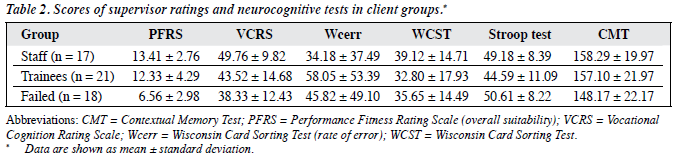

Supervisor Assessment

There was significant difference in PFRS scores between the groups (F = 20.234, p < 0.001). For the staff, the PFRS overall suitability score ranged from 8 to 18 with a mean (± standard deviation) of 13.41 ± 2.76; for the trainees, the score ranged from 1 to 20 with a mean of 12.33 ± 4.29; and for the failed cases, the score ranged from 2 to 10 with a mean of 6.56 ± 2.98 (Table 2). These 8 PFRS sub-items were found to have high internal consistency with the PFRS overall suitability score achieving the Cronbach’s alpha of 0.946.

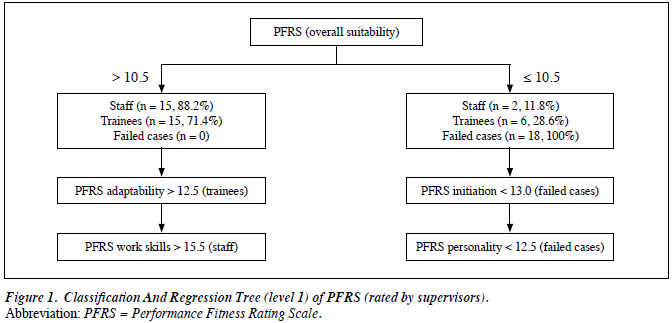

Hence, we used the PFRS overall suitability score to construct a model of association of all factors from the supervisors’ assessments. Generalised Rules Induction was used to determine a reliable cutoff point for ‘success’ and ‘failed’ clients. A CART was computed for PFRS overall suitability score against client groups. Nine fields were used to create a model with 91.2% overall accuracy. For those clients who received a PFRS overall suitability score of > 10.5, 30 (53.6%) of them were categorised as ‘success’ cases. Among the subscale ratings, initiation (< 13.0) and personality (< 12.5) were deciding factors for failure, while adaptability (> 12.5) and work skills (> 15.5) were desirable factors for consideration of recruitment. Nonetheless, no meaningful pattern emerged when categorising staff and trainee groups (Fig 1).

The supervisors simultaneously rated the performance of the 56 clients using VCRS. The total score demonstrated a significant difference across the 3 groups with a mean of 49.76 ± 9.82 for staff, 43.52 ± 14.68 for trainees, and 38.33 ± 12.43 for failed cases. There was also a significant difference among these 3 groups in VCRS total score (F = 3.576, p = 0.04). The visual analogue scale (on PFRS) had a highly significant correlation with VCRS total score (2- tailed test, r = 0.511; p < 0.001) as well as its 16 items (2- tailed test, r = 0.277-0.676; p < 0.05) which was a criterion- referenced tool with all personal variables controlled. Hence, VCRS may be a potential objective tool that can be used by a supervisor for job matching purposes at an SE unit with further local validation studies.

Therapist Assessment

The WCST were conducted to assess executive functions. The T score of total errors was analysed. The mean score was 39.12 ± 14.71 for staff, 32.80 ± 17.93 for trainees, and 35.65 ± 14.49 for failed cases.

The Stroop test was performed to assess mental flexibility. The mean interference T score was 49.18 ± 8.39 for staff, 44.59 ± 11.09 for trainees, and 50.61 ± 8.22 for failed cases.

The CMT was performed to assess contextual memory. The mean scores were 158.29 ± 19.97 for staff, 157.10 ± 21.97 for trainees, and 148.17 ± 22.17 for failed cases. No significant differences (95% confidence interval) were noted among these 3 groups for all neurocognitive assessments (WCST, Stroop test, and CMT).

The VCRS total score was correlated significantly with WCST score (p = 0.02) but not with other neurocognitive tests. Factor analysis was performed to explore the nature of workers’ abilities in prediction of their performance. From a total of 24 factors extracted using varimax-rotated principal component analysis, 4 principal components (with factor loading > 0.8) were identified that accounted for a cumulative 79.1% of variance, namely work-related cognition (VCRS, 49.8%), memory capacity and strategy (CMT, 12.9%), executive function (WCST, 10.8%), and directed attention (Stroop test, 5.6%). Hence, VCRS score might reflect additional applied functions and behaviours other than the basic cognitive functions measured by direct neurocognitive assessments (Table 3).

Model Development

Regression analysis was performed to predict PFRS overall suitability score from the 16 VCRS items and 3 neurocognitive tests of WCST, Stroop test, and CMT scores. A stepwise method was used and the model with the highest R value and using most of the fields was chosen (R2 = 0.918, F[41] = 3.794, p = 0.003]. A working model for therapists carrying out the assessment process was then created based on the above findings. The CART was used to identify the profile of ‘success’ and ‘failed’ clients using a PFRS (overall suitability) cutoff of 10.5. A 5-level decision tree was created using 22 fields with an overall accuracy of 0.861 (relative error, 0.26).

‘Success’ Profile

As revealed from the model, the successful participants were those with the key characteristics of: (1) being able to independently solve routine problems when they arise on the job; (2) continuing to work without slowing down when he / she sees or hears something interesting or different; (3) continuing to work without slowing down when small parts of the job divert his or her attention; (4) demonstrating an acceptable level of selective attention, cognitive flexibility, and processing speed; and (5) an acceptable level of short- term memory (Fig 2).

Discussion

Some studies have concluded that SE appears to work successfully by compensating the effects of cognitive impairment and symptoms at work.22 The methodology of using the subjective ratings of the existing supervisors as the gold standard was evidenced as appropriate and can be successfully quantified and broken down into individual component factors. It has not hitherto been usual practice for supervisors in the SE trade to categorise their internal standards of selection into different components, but to use an overall impression of performance that usually relies on daily observations. The VCRS, which is a valid criterion- referenced scale used in this study, successfully reflected the supervisors’ overall judgement in a highly consistent manner and is a potential means by which to rate daily performance.

The VCRS has been validated for similar groups of clients with MI in the United States15 but was introduced locally for the first time in this study. According to the factor analysis of all performance assessments in our study, VCRS total score contributed 49.8% of variance. The cognitive items measured by VCRS have shown significant correlation with the executive function scores in our study too. Further, VCRS was indicative of more applied functions than the basic cognitive abilities measured by the neurocognitive tests. These basic cognitive abilities accounted for another 29.5% of the variance in factor analysis results of the supervisors’ ratings in our sample. This echoed the findings from Bell et al23 that neurocognitive enhancement therapy, i.e. training of basic cognitive functions, in addition to traditional work behaviour simulated training, can improve vocational performance and can be sustained for a year.

Therefore, VCRS items assessed the overt and observable work-related behaviours and reflected the performance due to the client’s cognitive abilities. In this study, contextual memory, executive functions, and directed attention were important components in addition to work- related cognition, and contributed to the overall ‘success’ profile. This study demonstrated that the selection of sufficient assessment tools and subsequent development of the model were valid with 91.2% overall accuracy achieved.

The development of the decision pathway using data mining methodology is another important product of this study. The major objective of this study was to produce a valid clinical means to improve the accuracy and efficiency of occupational therapists’ work. Appropriate selection of assessment tools and making reference to the cutoff points of each tool can help the therapist to judge early on whether the client has the potential to succeed in SE. It facilitates a quick screening and decision-making process for the therapist as well as the client. The therapist can visualise the clients’ ability after working through the neurocognitive tests and predict their work-related performance in a systematic way. Insight development, especially helpful in clients with MI, was also reported by therapists during the study process.

Limitations

The sample in this study was small and covered only 1 NGO and a single job type, although it was the largest one in our local services. The demands of the supervisors might differ with another shop management team. The model developed is recommended for further validation by other SE teams with more clients.

Conclusion

The subjective ratings of the job supervisors in the SE unit and the content of their ratings were quantified, analysed, and validated against other criterion-referenced and neurocognitive assessment tests. The resultant model achieved an overall accuracy of 0.861 and could explain more than 90% of the variance captured for clients with MI in SE placement service. This methodology is pioneering in utilising both inference statistics as well as data mining techniques, where the study results can be more readily applied by therapists and subsequently guide the therapist in the choice of suitable assessment and training according to the needs of the SE markets. Further similar research is recommended for mental health services and psychosocial services that demand both a qualitative and quantitative display of evidence at a clinical level.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Mr SM Chu of Supported Employment Unit, New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association in providing assistance in case recruitment.

References

- Scheid TL, Anderson C. Living with chronic mental illness: understanding the role of work. Community Ment Health J 1995;31:163-76.

- McGurk SR, Wykes T. Cognitive remediation and vocational rehabilitation. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2008;31:350-9.

- Tsang HW, Chan A, Wong A, Liberman RP. Vocational outcomes of an integrated supported employment program for individuals with persistent and severe mental illness. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2009;40:292-305.

- Mueser KT, Clark RE, Haines M, Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Bond GR, et al. The Hartford study of supported employment for persons with severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:479-90.

- Michon HW, van Weeghel J, Kroon H, Schene AH. Person-related predictors of employment outcomes after participation in psychiatric vocational rehabilitation programmes — a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005;40:408-16.

- Becker DR, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Halliday J, Martinez RA. What predicts supported employment program outcomes? Community Ment Health J 2006;42:303-13.

- Jacobs HE, Wissusik D, Collier R, Stackman D, Burkeman D. Correlations between psychiatric disabilities and vocational outcome. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992;43:365-9.

- Wong KK, Chiu SN, Chiu LP, Tang SW. A supported competitive employment programme for individuals with chronic mental illness. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2001;11:13-8.

- Hoffmann H, Jäckel D, Glauser S, Kupper Z. A randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of supported employment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2012;125:157-67.

- Ng SS. Towards an understanding of the staged model of predictive reasoning [thesis]. United Kingdom: University of Leicester; 2009. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/2381/7868. Accessed Jan 2010.

- Elvevåg B, Goldgerg TE. Formal thought disorder and semantic memory in schizophrenia. CNS Spectrums 1997;2:15-25.

- Bryson GJ, Bell MD, Kaplan E, Greig TC. The Work Behaviour Inventory: A study of predictive validity. Psychiatr Rehabil J 1999;23:113-7.

- Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:321-30.

- Bell MD, Bryson G. Work rehabilitation in schizophrenia: does cognitive impairment limit improvement? Schizophr Bull 2001;27:269- 79.

- Greig TC, Nicholls SS, Bryson GJ, Bell MD. The Vocational Cognitive Rating Scale: a scale for the assessment of cognitive functioning at work for clients with severe mental illness. J Vocat Rehabil 2004;21:71- 81.

- Liberman RP, Green MF. Whither cognitive-behavioral therapy for schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull 1992;18:27-35.

- Golden CJ. Stroop Color and Word Test: a manual for clinical and experimental uses. Chicago, IL: Stoelting; 1978: 1-32.

- Toglia JP. Contextual Memory Test Manual. Available from: http:// www.innovact.co.za/Contextual%20Memory%20Test.htm. Accessed Jun 2009.

- Smith SM, Vela E. Environmental context-dependent memory: a review and meta-analysis. Psychon Bull Rev 2001;8:203-20.

- Freitas AA. A genetic algorithm for generalized rule induction. In: Roy R, Furuhashi T, Chawdhry PK, editors. Advances in soft computing — engineering design and manufacturing (Proceedings of the WSC3, The Third On-line World Conference, hosted on the internet, 1998). Springer-Verlag; 1999: 340-53.

- Breiman L, Friedman J, Olshen R, Stone C. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont, California: Wadsworth; 1984.

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT. Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and work in supported employment: a review and heuristic model. Schizophr Res 2004;70:147-73.

- Bell MD, Bryson GJ, Greig TC, Fiszdon JM, Wexler BE. Neurocognitive enhancement therapy with work therapy: productivity outcomes at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. J Rehabil Res Dev 2005;42:829-38.