East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:29-34

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

心理教育干預對改善單向抑鬱症的效果:隨機臨床試驗結果

A/Prof. Kuldip Kumar, Department of Psychiatry, Vardhman Mahavir Medical College & Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi 110029, India.

Dr Manushree Gupta, Specialist, Department of Psychiatry, GB Pant Hospital and Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi 110029, India.

Address for correspondence: Dr Manushree Gupta, B-7/22/1, Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi 110029, India.

Tel: (91) 9711195900 / (91-11) 2616 4489; Email:manushree@outlook.com

Submitted: 21 July 2014; Accepted: 25 September 2014

Abstract

Objectives: Depressive disorders are one of the leading components of the global burden of disease with a prevalence of up to 14% in the general population. Numerous studies have demonstrated that pharmacotherapy combined with non-pharmacological measures offer the best treatment approach. Psycho-education as an intervention has been studied mostly in disorders such as schizophrenia and dementia, less so in depressive disorders. The present study aimed to assess the impact of psycho- education of patients and their caregivers on the outcome of depression.

Methods: A total of 80 eligible depressed subjects were recruited and randomised into 2 groups. The study group involved an eligible family member and all were offered individual structured psycho- educational modules. Another group (controls) received routine counselling. The subjects in both groups also received routine pharmacotherapy and counselling from the treating clinician and were assessed at baseline, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), and Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI). Results from both groups were compared using statistical methods including Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t test, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, as well as univariate and multiple regression analyses.

Results: Baseline socio-demographic and assessment measures were similar in both groups. The study group had consistent improvement in terms of outcome measures with HDRS, GAF, and PGWBI scores showing respective mean change of -15.08, 22, and 60 over 12 weeks. The comparable respective changes in the controls were -8.77, 18.1, and 43.25.

Conclusion: Structured psycho-education combined with pharmacotherapy is an effective intervention for people with depressive disorders. Psycho-education optimises the pharmacological treatment of depression in terms of faster recovery, reduction in severity of depression, and improvement in subjective wellbeing and social functioning.

Key words: Depression; Psychotherapy; Randomized controlled trial; Treatment outcome

摘要目的:抑鬱症是全球主要的疾病負擔之一,現患率可高達一般人口的14%。許多研究已經表明藥物治療結合非藥理學措施為最佳治療方法。有關心理教育干預對各種精神病患如精神分裂症和老年癡呆症等的效用已被廣泛討論,唯對抑鬱症的討論則較少。因此,本研究旨在檢視對病人和照顧者進行心理教育對治療抑鬱症效果的影響。

方法:納入80名合資格抑鬱受試者並隨機分為2組:其中一組加入符合條件的家庭成員並接受獨立結構化心理教育,另一組則接受常規輔導(對照組)。兩組受試者皆接受常規藥物治療和臨床醫生輔導,然後評估他們在基線以及第2週、4週、8週和12週的漢密爾頓抑鬱量表(HDRS)、全球功能評估量表(GAF)以及心理總體福祉指數(PGWBI)得分。兩組結果以各種統計分法作比較,包括卡方檢驗、費氏精確檢定、t檢驗、Pearson相關係數以及一元和多元迴歸分析。

結果:兩組的基線社會人口和評估措施相若,而獲結構化心理教育的患者其改善較有效果,其HDRS、GAF和PGWBI在12週後的平均改變得分分別為-15.08、22和60;而對照組的相對改變得分為-8.77、18.1和43.25。

結論:結構化心理教育結合藥物治療是治療抑鬱症的有效干預。心理教育可優化對抑鬱症的藥物治療,加快患者的康復進度並改善其抑鬱症重度以及主觀福祉和社會功能。

關鍵詞:抑鬱症、心理治療、隨機對照試驗、治療效果

Introduction

Depression is a major health problem and currently recognised as a leading global cause of morbidity. The report on global burden of disease estimates the point prevalence of unipolar depressive episodes to be 1.9% for men and 3.2% for women.1 The 1-year prevalence has been estimated to be 5.8% for men and 9.5% for women.1 If current trends for demographic and epidemiological transition continue, the burden of depression is projected to increase to 5.7% of the total burden of disease by 2020.1 It would be the second leading cause of disability-adjusted life years, second only to ischaemic heart disease.1 A high prevalence of depressive disorders has also been reported from community samples in India.2,3

The risk of recurrence of depression increases with each successive episode.4 Current medications are hampered by major shortcomings which include slow onset of action, poor efficacy, and unwanted side-effects; a better mutual understanding is warranted between mental health providers and receivers, thereby increasing the role of family members and caregivers. Research on involvement of caregivers is mostly related to chronic schizophrenia,3 dementia disorders,4 and other older mental patients5 but less in relatively common conditions such as depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.6 Although as clinicians we routinely guide patients and their relatives, a gap exists between evidence-based treatment and clinical care.

Studies have shown that in India, 98.3% of depressed patients live with their families compared with 50% in western countries.7,8 The family is without doubt a major source of support for psychiatric patients and Indian families show a lot of resilience in caring for their depressed family members. They nonetheless also feel a significant emotional, financial, and physical burden, although this may not be openly acknowledged. There is greater cooperation and involvement of family members in treatment decisions, career choices, and marriage for Indian psychiatric patients.9

Numerous psychological interventions are available for treating depression, of which psycho-education has been shown in both clinical and community trials to be very effective.10,11 Psycho-educational interventions involve individuals with psychological disorders or physical illnesses and their family members. The term “psycho-education” was first employed by Anderson et al12 and was used to describe a behavioural therapeutic concept that involved both patients and their relatives and consisted of 4 elements: briefing patients about their illness, problem-solving training, communication training, and self-assertiveness training. Important elements in psycho- education are: (1) information transfer (symptomatology of the disturbance, causes, treatment concepts, etc.); (2) emotional discharge (understanding to promote exchange of experiences with others concerned, contacts, etc.); (3) support of a medical or psychotherapeutic treatment, as cooperation is promoted between the mental health professional and patient (compliance, adherence); and (4) assistance to self-help (e.g. training, so crisis situations are promptly recognised and steps taken to help the patient).

It seems widely accepted that one of the mechanisms by which psychosocial educational interventions are effective is in the creation of a positive cycle involving treatment and rehabilitation. Adhering to a prescribed drug regimen allows an individual to take part in psychosocial interventions that may in turn increase the knowledge of his or her mental illness and its treatment, thereby further facilitating compliance with the drug regimen. Colom and Lam13 argued that psycho-education is based on a tripod model composed of lifestyle regularity and healthy habits, early detection of prodromal signs, and treatment compliance. It is based on individual’s strengths and focused on the present. The patient / client and / or family are considered partners with the provider in treatment, on the premise that the more knowledgeable of the care recipients and informal caregivers are, the more positive the health-related outcomes will be for all. Psycho-educational interventions are less expensive, more easily administered, and potentially more accessible than conventional pharmacological and psychological interventions. In addition, there is some evidence from systematic reviews14,15 that psycho-educational interventions are effective in the treatment or prevention of mental disorders.

In the management of mild-to-moderate symptoms of depression, psycho-education effectively reduces symptoms in adults and can prevent depression in primary care patients. Most international clinical practice guidelines16,17 for the management of depression recommend psycho-educational intervention and brief psychotherapy as the first step in the treatment protocol. A recent study18 also examined the role of psycho-education and the expressed emotions in the time to relapse in depressed outpatients. This study found significant benefits of family psycho-education in terms of fewer relapses.

The present study aimed to assess the impact of psycho-education of patients and their caregivers on the outcome of unipolar depression in terms of rate of recovery, remission of symptoms, as well as improvement in social functioning and general wellbeing.

Methods

The study was conducted at the Department of Psychiatry of Vardhman Mahavir Medical College & Safdarjung Hospital, India between April and June 2012. A total of 80 eligible subjects were recruited and randomised alternately into 2 groups.

The study group included patients with their respective caregiver. An eligible caregiver was defined as a family member, friend, or significant other who satisfied the greatest number (and at least 3) of 5 criteria: (1) was a spouse, parent, or spouse equivalent; (2) had the most frequent contact with the patient; (3) helped to support the patient financially; (4) had been the most frequent collateral participant in the patient’s treatment; and (5) was the person contacted by treatment staff in case of emergency.19 Another group included newly diagnosed subjects who fulfilled the World Health Organization ICD-10 criteria for depressive disorder.20 For the purpose of comparative study, this group served as controls.

Exclusion criteria for patients included: (1) any major co-morbid physical illness; (2) co-morbid psychiatric illness; (3) substance use disorder (not occasional use); (4) bipolar mood disorder; (5) partially treated or current treatment for depression; and (6) age < 14 or > 60 years.

Exclusion criteria for caregivers included: (1) aged < 18 years; (2) significant medical or mental disorder; and (3) alcohol or other substance use disorder. The caregiver did not change throughout the study.

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Four specially designed psycho-education modules for subjects and their caregivers were initiated at baseline, 2, 4, and 8 weeks in the study group (Table 1). The psycho-education sessions were carried out by a researcher other than the treating psychiatrist. Depressed patients in both groups were monitored by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS),21 Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF),22 and Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI)23 at baseline, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. To minimise bias, outcome measures were rated by a psychiatrist not involved in the psycho-education.

The final outcome of depression was analysed at the end of 12 weeks by comparing the data of both groups using Chi-square test, Fischer’s exact test, Student’s t test, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, as well as univariate and multiple regression analyses. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Non-parametric data were analysed using Mann-Whitney test. Binomial test was used to test proportion.

As the study was designed to evaluate the role of psycho-education, the treating clinician was absolutely free to continue the treatment of his / her own choice. Both groups also received the routine unstructured counselling.

Results

A total of 80 subjects were recruited for the study. Of these, 40 were categorised into study (intervention) group and the other 40 as controls. In the study group 2 cases were lost to follow-up, whereas 6 individuals in the control group dropped out during the study.

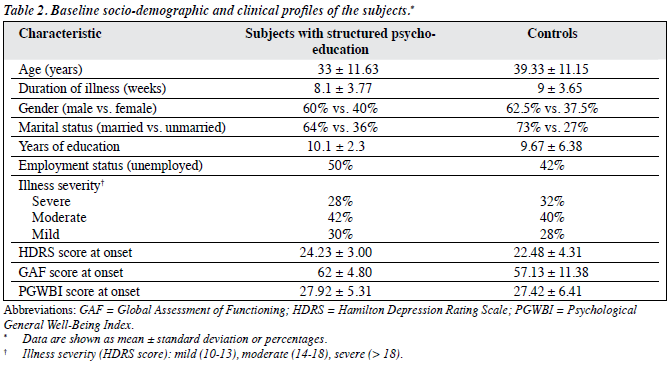

The mean age of patients in the study group was 33 years and that of their caregivers was 39 years. In all, 60% of the patients and 57% of their caregivers were male. The illness severity distribution at baseline in both study and control groups was similar: 28% and 32% of subjects had a severe depressive episode, respectively. Table 2 shows the comparative baseline socio-demographic and clinical details of the study population.

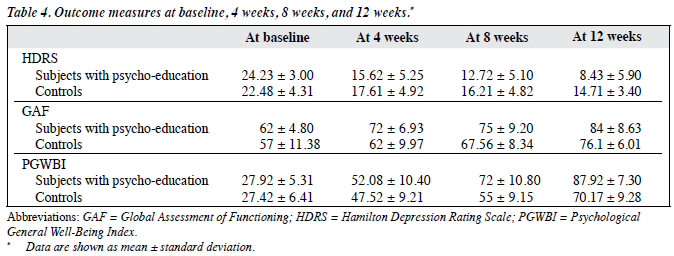

The mean baseline HDRS, GAF, and PGWBI scores were comparable in both groups, and that they scored lowest on the depression subscale (intervention group vs. controls, 3.93 vs. 4.12) and the self-control subscale (4.23 vs. 4.00) of the PGWBI at baseline.

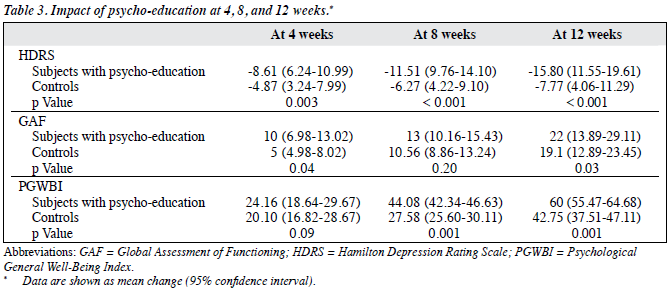

The mean HDRS scores in both groups started to separate between baseline and at 4 weeks. At 4 weeks, the reduction in mean HDRS score in the intervention group was almost twice than that of the controls (p < 0.003). Likewise, the increase in GAF scores in the intervention group was significant (p < 0.04) [Table 3].

At 8 weeks, the outcome measures began to show substantial difference between the study and control groups, reaching a peak at 12 weeks (Table 4). The difference in mean HDRS score reduction between the 2 groups at 12 weeks was highly significant (p < 0.001) [Table 3].

Subjective scores on the PGWBI showed the most significant increase among the 3 parameters (HDRS, GAF, PGWBI) used (Tables 3 and 4). The difference in mean PGWBI increase was highly significant at both 8 and 12 weeks in both groups (p < 0.001). The mean increase was especially noticeable in the depressive (8.35) and general health (8.10) PGWBI subscales in the study group; respective increase was 6.22 and 5.62 in the controls.

Discussion

The results of this study on the effect of psycho-educational intervention on depressed subjects and their caregivers showed a significant effect on depression and psychological distress in the psycho-education group compared with the control group. Cuijpers14 found that active psycho- educational intervention improved functioning. The active interventions in the same review14 were based on cognitive behaviour techniques and the study duration of 4 to 11 weeks was similar to the present study.

Our study provides follow-up data at 12 weeks, similar to other studies of depressive disorders.24,25 The follow-up was naturalistic as the treating physicians were free to prescribe whatever pharmacological treatment they deemed appropriate for their patients.

As evident from Table 4, the improvement in depressive symptoms in the 2 groups commenced at the outset and showed a significant difference throughout the study period. The mean HDRS score difference between the 2 groups became significant at 4 weeks (p < 0.003) and was highly significant (p < 0.001) at 12 weeks.

This finding may lead to important assumptions. According to several studies,26,27 the greatest suicide risk in depressed subjects is during the resolution phase, therefore this study might have important implications. Psycho-educational interventions in such individuals might decrease suicide risk due to better education of subjects and their caregivers and faster symptomatic recovery early in the course of the illness. An important finding during the 12 weeks of this study was that the key points on the HDRS for assessing suicidal tendency, i.e. outlook (item 1), feelings of guilt (item 2), suicide (item 3), and suicidal ideation (item 18) showed a consistent decline in the intervention group. Although HDRS is often criticised for its failure to adequately assess suicide risk,28 this finding emphasises the need for better assessment of suicidal tendency with psycho- educational intervention and more elaborate instruments.

The 2 groups started to exhibit significant difference in various mean outcome scores from 8 weeks onwards. It was highly significant that the largest difference between the 2 groups was evident in the PGWBI mean score: 87.92 and 70.17 in the intervention and control groups, respectively at 12 weeks (p < 0.001). The mean increase was especially noticeable in the depressive (8.35) and general health (8.10) PGWBI subscales in the intervention group. The corresponding increase in the controls was 6.22 and 5.62. As a subjective measure, the PGWBI better reflected psychological wellbeing of the subjects in the intervention group compared with the controls. A recent study also used PGWBI for comparing mindfulness-based cognitive behaviour techniques to psycho-education, with follow-up at baseline, 4, and 8 weeks.29

In our study, the various mean outcome scores at 8 weeks in the intervention group and that at 12 weeks in the controls were similar. This observation may be significant in terms of conferring a shorter duration in achieving remission in depressed subjects when pharmacotherapy is combined with psycho-education. This finding is supported by earlier studies which found combined therapy to be superior to psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy alone.30 Another study31 could not provide the same conclusive evidence as the percentage of patients with major depression who recovered after 12 weeks of treatment were as follows: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors 47%, behavioural therapy 55%, cognitive psychotherapy 47%, and combination therapies 35% to 54%. This randomised controlled trial31 carried out in a primary care setting also concluded that psycho-educational treatment was most likely to benefit patients with a depressive disorder of moderate severity and who wished to participate in an active psychological treatment.

Evidence for the utility and cost-effectiveness of psycho-education for relapse prevention in depression has also come from a recent study from Japan.32 This study concluded that family psycho-education effectively prevents relapse of depression and is highly likely to be cost-effective if a relapse-free day is valued as ≥ US$20. Our study did not confer any additional treatment cost burden on the patient chosen for psycho-education.

Limitations

This study was limited by the restricted follow-up of outcome measures and longer study duration might have assessed the sustainability of the effects of psycho-education. The study also did not control for the duration of counselling provided by the treating psychiatrist, and this might be a confounding factor in the results. The study group might have benefitted more by the additional time spent with the clinician while receiving the psycho-education sessions. Also, the study was carried out in a naturalistic setting and did not control for pharmacological effects on the outcome of illness.

Conclusion

Psycho-education optimises pharmacological treatment of depression in terms of faster recovery, reduced severity of depression, and improvement in subjective wellbeing and social functioning. Psycho-education may also offer an early and effective protection against suicide risk in depressed patients, as evidenced by the preliminary findings of this study. Structured psycho-education combined with pharmacotherapy may be recommended as an effective intervention for people with depressive disorders.

This study should influence psycho-educational interventions in psychiatric clinical care, especially in developing countries where economic and social sustainability are dependent on faster and robust recovery from depressive conditions.

Declarations

The authors declared no funding from any external source and no conflict of interest in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Dr Rajesh Rastogi, Head of the Department of Psychiatry, Vardhman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital for his kind guidance and permission for study. Our sincere thanks to Prof. R. K. Chadda, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi for critically reviewing the paper. We indeed appreciate the efforts of Dr Madhusudan Solanki, Senior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Vardhman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital for his contribution to data collection. Lastly, we thank all our patients and family members for participating in the study.

References

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global burden of disease and risk factors. Washington: The World Bank; 2006: 45-240.

- Reddy MV, Chandrashekar CR. Prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders in India: a meta analysis. Indian J Psychiatry 1998;40:149-57.

- Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Mukherjee SP, Ghosh A, Nandi PS, Nandi S. Psychiatric morbidity of a rural Indian community. Changes over a 20-year interval. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:351-6.

- Papastavrou E, Tsangari H, Karayiannis G, Papacostas S, Efstathiou G, Sourtzi P. Caring and coping: the dementia caregivers. Aging Ment Health 2011;15:702-11.

- Sakurai N. The moderating effects of positive appraisal on the burden of family caregivers of older people [in Japanese]. Shinrigaku Kenkyu 1999;70:203-10.

- Vikas A, Avasthi A, Sharan P. Psychosocial impact of obsessive- compulsive disorder on patients and their caregivers: a comparative study with depressive disorder. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2011;57:45-56.

- Dani MM, Thienhaus OJ. Characteristics of patients with schizophrenia in two cities in the U.S. and India. Psychiatr Serv 1996;47:300-1.

- Sharma V, Murthy S, Agarwal M, Wilkinson G. Comparison of people with schizophrenia from Liverpool, England and Sakalwara- Bangalore, India. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1998;44:225-30.

- Heitzman J, Worden RL. India: a country study, area handbook series. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1996.

- Murray-Swank AB, Dixon L. Family psychoeducation as an evidence- based practice. CNS Spectr 2004;9:905-12.

- 1 Donker T, Griffiths KM, Cuijpers P, Christensen H. Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. BMC Med 2009;7:79.

- Anderson CM, Hogarty GE, Reiss DJ. Family treatment of adult schizophrenic patients: a psycho-educational approach. Schizophr Bull 1980;6:490-505.

- Colom F, Lam D. Psychoeducation: improving outcomes in bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry 2005;20:359-64.

- Cuijpers P. Bibliotherapy in unipolar depression: a meta-analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1997;28:139-47.

- Merry S, McDowell H, Hetrick S, Bir J, Muller N. Psychological and / or educational interventions for the prevention of depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(1):CD003380.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health commissioned by the National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence (NICE). The NICE guideline on the treatment and management of depression in adults (updated edition). The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2009.

- Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

- Shimazu K, Shimodera S, Mino Y, Nishida A, Kamimura N, Sawada K, et al. Family psychoeducation for major depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2011;198:385-90.

- Pollak CP, Perlick D. Sleep problems and institutionalization of the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1991;4:204-10.

- World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: WHO; 1992.

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967;6:278-96.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Dupuy HJ. The psychological general well-being (PGWB) index. In: Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Fuberg CP, editors. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. New York: Le Jacq; 1984.

- Geisner IM, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. A randomized clinical trial of a brief, mailed intervention for symptoms of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:393-9.

- Jacob KS, Bhugra D, Mann AH. A randomised controlled trial of an educational intervention for depression among Asian women in primary care in the United Kingdom. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2002;48:139-48.

- Healy D, Whitaker C. Antidepressants and suicide: risk-benefit conundrums. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2003;28:331-7.

- Jick H, Kaye JA, Jick SS. Antidepressants and the risk of suicidal behaviors. JAMA 2004;292:338-43.

- Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Marshall MB. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry 2004;16:2163-77.

- Chiesa A, Mandelli L, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus psycho-education for patients with major depression who did not achieve remission following antidepressant treatment: a preliminary analysis. J Altern Complement Med 2012;18:756-60.

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, Andersson G. Psychotherapy versus the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety 2009;26:279-88.

- Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Day A, Baker F. Randomised controlled trial of problem solving treatment, antidepressant medication, and combined treatment for major depression in primary care. BMJ 2000;320:26-30.

- Shimodera S, Furukawa TA, Mino Y, Shimazu K, Nishida A, Inoue S. Cost-effectiveness of family psychoeducation to prevent relapse in major depression: results from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:40.