Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2006;16:50-56

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

DFK Wong, SYK Sun

Dr Daniel Fu Keung Wong, Associate Professor, Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Mr Stephen Yu Kit Sun, Lecturer, Division of Social Studies, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Daniel Fu Keung Wong, Associate Professor, Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, 1317 KK Leung Building, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 2859 2096; Fax: (852) 2858 7604;

E-mail: dfkwong@hkucc.hku.hk

Submitted: September 14 2006; Accepted: November 15 2006

Abstract

Objective: This study used a randomised waitlist control design to examine the efficacy of cognitive-behavioural group therapy for Chinese people with social anxiety in Hong Kong.

Patients and Methods: In total, 34 Chinese participants with social anxieties were randomly assigned into experimental and control groups. The participants in the experimental group received a 10-session cognitive-behavioural therapy group treatment, while participants of the control group did not. Outcome measures included The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, Emotions Checklist, Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Scale and Dysfunctional Attitude Scale. Results: Preliminary findings suggested that subjects receiving group cognitive-behavioural therapy showed significant decrease in social anxiety, dysfunctional rules and negative emotions and significant increase in adaptive coping skills and positive emotions compared with the control group.

Conclusion: These findings provide initial evidence of the efficacy of group cognitive-behavioural therapy for Chinese people with social anxieties. Future research should use a larger sample and examine the longer term effect of group cognitive-behavioural therapy.

Key words: Anxiety disorders, Chinese, Cognitive behavior therapy, Group psychotherapy, Hong Kong

Introduction

The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) for social anxiety has been demonstrated in several con- trolled trials and meta-analyses.1,2 Treatment effects of CBT are found to be superior to other treatment modalities such as educational-supportive group,3 and combined medication and behaviour therapy (selective serotonin reuptake in- hibitor treatment plus weekly self-exposure exercises).4 A few studies have also found that long-term effects of CBT were maintained at six and twelve months' follow- up5 and five years' follow-up.6 However, several studies have also affirmed the treatment efficacy of CBT when carried out in the CBT group format.5,7 Indeed, Heimberg et al suggest that the CBT group has potential benefits which include greater ease in simulating social situations in role plays, mutual support from group members, potentially helpful social comparisons, and vicarious learning while other group members are performing role plays.8 Despite this evidence, very little is known as to how CBT group can be applied to Chinese people and how effective it is.

Cognitive-behavioural Perspective of Social Anxiety

Based on information processing theory, Clark and Wells outline a cognitive model of social phobia and suggest that persons with social anxiety choose negative interpretations of ambiguous social events, and rate their performances and behaviours rather negatively.9 Rapee and Heimberg further maintain that individuals with social anxiety engage in bi- ased and erroneous appraisals of social situations10 which include attentional bias,11 judgmental bias,12 and inter- pretation bias.13 It has also been suggested that people with social anxiety are often hypervigilant of their own somatic symptoms and are very attentive to detailed monitoring and observation of themselves. They tend to engage in anticipa- tory and postevent processing, examining in great detail what and how they would respond to social events and what they did wrong in those situations. Behaviourally, people with social anxiety tend to engage in safety behaviours to reduce social threat and prevent fearful outcomes from occurring. Unfortunately, these safety behaviours, such as avoiding eye contact and trying very hard to present well in front of others, are often maladaptive. Bond and Dryden maintain that these biased and erroneous appraisals of social events are intimately related to the dysfunctional assumptions and beliefs held by people with social phobia.14 Wells and Matthews propose that people with social anxiety tend to view themselves as vulnerable and feel themselves inadequate in social performance.15 These people believe that they cannot control what is happening in a social event and cannot per- form adequately in the situation. Therefore, they often adopt biased negative and critical appraisals of their own social performance and expect others to judge them negatively.

On the other hand, Freeman et al suggest that people with social phobia tend to demand approval from others.16 When they do not receive positive feedback from others, they become anxious about their own performances. The third theme or category of belief found in people with social phobia is perfectionism. Juster et al17 and Lundh and Öst18 found that people with social anxiety tend to set ex- cessively high standards and are overly critical of failure to meet those standards. Alden and Wallace further elaborate on this point, saying that these expectations are usually not externally imposed on people with social anxiety, but are internally generated and assumed by the persons to be standards set by others.19

In summary, CBT aims to help individuals with social anxiety: (1) to understand and correct negative and biased interpretations of social events; (2) to understand and modify dysfunctional beliefs; (3) to learn to abstain from engaging in safety behaviours; and (4) to gradually approach and adapt to anxiety-provoking social events.

Application of Cognitive-behavioural Therapies for Chinese

Lin maintains that cognitive-behavioural therapies may be appropriate for Chinese.20 It has been suggested that Chinese people tend to be less tolerant of ambiguity and prefer structured counselling sessions with practical and immediate solutions to their problems.21 Therefore, CBT which emphasises a structured and systematic counselling process with the step-by-step learning of new cognitive and behavioural skills would suit the cultural orientations of Chinese people.20 Moreover, Chinese people prefer therapists who employ a directive rather than a non-directive approach. As suggested by Lin, therapists are perceived as effective by Chinese clients when they take partial responsibility for the process and play an active role in providing suggestions and advice and facilitate clients' actions.20 Thus, CBT which stresses the directive and collaborative roles of a therapist may be suitable for Chinese people.

Lee and Choy carried out an outcome study of CBT for Korean people with social anxiety.22 They found that par- ticipants in their study had a lower level of social anxiety and less fear of negative evaluation after treatment. In Hong Kong, there is little empirical research on structured group CBT. Two local studies on the use of CBT focused on persons who were at risk of developing poor mental health,23 and depressed individuals.24 However, no study on the application of group CBT for people with social anxiety has ever been conducted in Hong Kong.

The main objectives of this study were: (1) to examine the efficacy of CBT group in treating people with social anxiety; and (2) To explore the relationships between dys- functional attitudes and social anxiety, coping skills and positive and negative emotions.

There were two hypotheses.

- The members of the experimental group would report less social anxiety, fewer dysfunctional attitudes, more adaptive coping skills, more positive emotions, and fewer negative emotions than those of the control group at the end of the group intervention.

- Changes in dysfunctional attitudes would be significantly related to changes in social anxiety, coping skills and positive and negative emotions of members.

Patients and Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited either from clinical referrals or advertisements posted at hospitals and psychiatric clinics. All potential participants, after passing a telephone screening, were offered a pre-group interview. Inclusion criteria included: (a) age 18-60 years; (b) showing symp- toms of social anxiety stated in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV); and (c) social anxiety considered to be the most severe disorder when comorbidity of disorders was present. Exclusion criteria included: (a) the presence of psychotic symptoms and substance abuse defined by DSM-IV; and (b) the presence of severe mood disorders. Individuals who had psychosis, severe mood disorders and substance abuse were referred to other services for psychiatric assessment and treatment. Those who were reluctant to participate in the group process were also excluded from the study. Finally, 34 individuals participated in the study after the pre-group interview. To randomly assign participants into the ex- perimental and waitlist conditions, a simple randomisation procedure was adopted. Each participant was given a number. A staff member with no knowledge of the research was asked to draw the numbers from a box. Every second number drawn from the box would become a participant of the experimental groups. The remainder were waitlisted. This project was reviewed and endorsed by the Committee on Research and Conference Grant of the University of Hong Kong. All participants had to sign a consent form which contained details regarding the purpose of the research and the extent of their involvement.

Procedure

All participants were administered the baseline psychomet- ric tests. The same questionnaire was repeated at the end of the treatment and the waiting period (i.e., post-test). Based on the manual written by Hope et al for people with social anxiety, we developed a structured CBT treatment for participants in the experimental group between the times of measurement, whereas no treatment was given to the participants in the control group.25 Participants in the control group were given group treatment after the control group study had finished. The three group leaders were experienced mental health social workers. Two of them were teaching staff in universities, one of whom was a qualified cognitive therapist trained from the Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy and Research. The third one was a social worker with postgraduate training in mental health. A total of two CBT groups were run and each group had 8 to 9 members. There were 10 weekly sessions per group, with each session lasting 2.5 hours. The two groups followed the same CBT protocols developed by the research team.

Contents of Group Cognitive-behavioural Therapy

In the original manual written by Hope et al, the contents include: (1) educating the person with anxiety about the in- teraction and connection among different response patterns which lead to anxiety outcomes — physiological responses, cognitive responses and behavioural responses; (2) identi- fying the dysfunctional thinking patterns — automatic thoughts and dysfunctional beliefs; (3) developing cogni- tive and behavioural strategies to deal with one's anxieties; (4) engaging in real-life exposure; and (5) identifying and dealing with core beliefs.25

Based on the above strategies, we added some charac- teristics to improve cultural relevance. First, all terminolo- gies were translated into colloquial Chinese. For example, "automatic thoughts" was renamed as "thought traps"; cog- nitive distortions, such as "personalisation", was rephrased as "put all the blame and responsibilities onto oneself", and "minimisation" was termed as "minimising one's achieve- ments". Secondly, all group sessions were structured. To facilitate group learning and discussion, we developed a number of exercises and worksheets. Thirdly, the group lead- ers were active and interactive in facilitating the process. The general attitude held by the group leaders was one of guided discovery.26 Essentially, the roles of the leaders were to facilitate the participants to achieve self-discovery and to develop a sense of self-efficacy towards modifying their dysfunctional patterns of thinking and behaviours. Fourth, the participants were asked to develop a hierarchy of social anxiety situations and to practise the use of the cognitive and behaviour strategies such as thought stopping, positive self-talk, distraction and the use of cue cards. Thus, each participant had to develop their own strategies and prac- tised the skills in the group and in the real-life settings. Fifth, through guided discovery, participants had the opportunity to examine their own dysfunctional rules and how those rules affected their social anxieties. Particular attention was put to helping the participants understand the rigidity and consequences of holding onto the rules; and facilitate them in rewriting the rules to make them more flexible and reasonable. Lastly, in the last two sessions, we added a new content which facilitated the participants to examining and making plans to change their stress-inducing lifestyles. Such an inclusion was based on Scholing and Emmelkamp's recommendation that "it seems important to direct treatment at more structural changes in patients' lives.27

Two independent observers reviewed the videotapes of sessions 1, 4 and 8 of each experimental group. The con- tents of the three sessions revolved around "understanding the relationships among cognitive, behavioural, physiologic- al and emotional responses", "identifying automatic thought patterns and developing healthy cognitive and behavioural responses" and "identifying and modifying dysfunctional rules". Since the group contents were manualised, it was easier for the research team to develop a checklist of the tasks to be completed in the three sessions. The two reviewers were asked to check each of the items in the checklist and assess whether the group leaders had completed the pre- scribed tasks. The two reviewers agreed on the tasks to be completed by the group leaders.

Although the groups were structured and manualised, the group leaders made use of the group dynamics to help members acquire the cognitive and behaviour skills in man- aging their emotions. To begin with, through the use of worksheets and exercises, group members were encouraged to focus and share their views on the issues under discussion. With prompting and encouragement, members were able to give feedback to and even openly challenge one another's thoughts and behaviours.The group leaders were also cognisance of the importance of creating a supportive atmos- phere for the group members. This turned out to be some- thing of a lesser concern because anxiety problems became a strong common bond for the group members. Indeed, they were able to understand the "sufferings" experienced by others such as the inability to control anxiety symptoms, and the fear of social embarrassment. Rather it was neces- sary for the group leaders to help members balance their need for expressing their emotions and to develop adaptive cognitive and behaviour skills in managing their emotions. Lastly, an important task of the group leaders was to instill hope among members. Through various exercises such as the emotion thermometer and homework, participants were encouraged to observe the successful experiences of some members in managing their anxieties. More importantly, we helped members pick up the subtle positive changes that they or other members had overlooked. By building on "these positives", we helped members acquire a sense of control over their anxieties.

Outcome Measures

The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) was originally developed as a clinician-administered scale to assess the degree of fear and avoidance of 24 social situations rated by the respondents.28 Each situation was rated for fear and avoidance experienced by the respondent in the previous week on a 0-3 Likert-type scale. Previous studies have shown that this version possessed generally good psychometric properties, indicated by its high internal consistency and test-retest reliability, and good convergent and discrimin- ant validity.29 In the present study, the self-report version (LSAS-SR) was used. When comparing the psychometric properties of the LSAS-CA and LSAS-SR, Fresco et al found that both versions were virtually identical, with high internal consistency, and strong convergent and discrim- inant validity.30 In this study, a reduction in the total score came to signify a decrease in a member's social anxiety level. The LSAS-SR achieved excellent internal consistency in this study (Cronbach's alpha (a), pretest = 0.96).

The Positive and Negative Emotions Checklist, consist- ing of the positive and negative dimensions, was derived by the researchers based on the original version developed by Cormier and Hackney.31 Group members were asked to choose as many negative and/or positive emotions on the checklist as they felt appropriate in describing their emo- tional states during the week they filled out the questionnaire. The number of positive and negative emotions was summed up to form two individual scores for negative emotions and positive emotions. Changes in the number of negative and positive emotions before and at the end of the group session would indicate an increase or a decrease in positive and negative emotions. Since this is not a Likert-type scale; no psychometric properties have been performed.

The Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) Scale was developed by Carver et al32 and was further modified in a local study by Lam.33 The original version of the COPE Scale had 13 dimensions and was designed for measuring both adaptive coping (e.g., active coping and positive reinterpretation of events), and mal- adaptive coping (e.g., denial and avoidance). This scale was demonstrated to have high internal consistency, and strong convergent and discriminant validity. In this study, an increase in a member's total score at the end of the group came to signify an increase in the utilisation of adaptive coping skills. This scale achieved a reasonable level of internal consistency in this study (Cronbach's a = 0.67).

The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) was adopted and translated from Weissman and Beck's original scale.34 The DAS 40-item Form A was used in the present study. This scale attempted to tap the dysfunctional beliefs held by the participants, and was supposed to reflect the content of one's cognitive schema.35 Participants rated each item on a 1-7 scale, ranging from 1 = totally agree to 7 = totally disagree.It had high internal consistency and test-retest reliability.34 It was assumed that the fewer dysfunctional beliefs a person had, the more functional was the person's cognitive processes. This scale achieved a high level of internal consistency in this study (Cronbach's a = 0.90).

Data Analysis

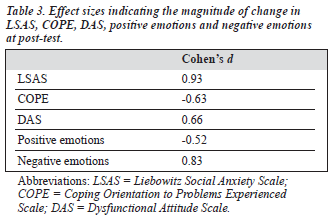

All data analyses were primarily conducted for the partici- pants who completed the treatment or the waiting period. Differences between the experimental group and the con- trol group were examined employing analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with the pretest score of each outcome measure, gender, education and marital status treated as the covariates, so that the post-group outcome could be adjusted with respect to the baseline severity. In order to check if the pretest values were differentially predictive of the outcome for the experimental and control groups, the assumption of homogeneity of regressions was assessed before ANCOVA were performed. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's d (the difference between adjusted means divided by the pooled standard deviation (SD) to examine the magnitude of the differences between the experimental and control groups at post-test.36

Results

Demographic and Baseline Analyses

Originally, there were 39 applicants who wanted to join our CBT group. Five were excluded because they did not think that the group would benefit them (n = 2), preferred indi- vidual counselling (n = 1), were referred to private psych- iatrist (n = 1) or had a very recent suicidal attempt (n = 1). All 34 participants finished the treatment or the waitlist period. There was no dropout in the present study. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants. The mean age of participants was 34.9 years (SD, 9.6). Almost 62% were unmarried (n = 21) and 35.3% were married (n = 12). More than half of the participants had completed their secondary education (n = 18, 53%), and 44.1% of them had even received tertiary education (n = 15). A vast majority of the participants had full-time employment (n = 23, 67.6%); 26.5% were unemployed (n = 9). The mean duration of illness was 7.6 years (SD, 6.2). All participants were taking medications (yes/no response). However, details of specific medications were not sought (Table 1).

Demographic data of the experimental and the control groups were compared, using Mann-Whitney U tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. The analysis found no significant differences between experimental and control groups on all demographic variables (p > 0.05), in- dicating that the experimental group and the control group shared similar characteristics before treatment began for the experimental group. ANOVA were also used to compare the pretest scores of all outcome variables between the experi- mental and the control groups. No significant differences were found between the two groups (p > 0.05).

Between-group differences were analysed using ANCOVA. For all analyses of post-intervention outcomes, there was no evidence for the homogeneity of regression assumption to be violated, indicating that baseline severity was not differ- entially predictive of the outcomes for the treatment and control groups (i.e., there was no evidence for an interaction between the covariate and the treatment). ANCOVA showed that there were significant between-group differences in LSAS, (F [1, 31] = 17.70, p < 0.001; COPE, F [1, 31] = 6.03, p = 0.02); positive emotions, (F [1, 31] = 13.58, p < 0.001); negative emotions, (F [1, 31] = 6.20, p = 0.02; and DAS, F [1, 31] = 8.46, p = 0.01). The analysis revealed that experi- mental group members, when compared with the control group, showed less social anxiety, more adaptive coping skills, more positive emotions, fewer negative emotions, and fewer dysfunctional attitudes (Tables 2 and 3).

According to Cohen, effect size can be thought of as the average percentile standing of the average treated (or experi- mental) participant relative to the average untreated (or control) participant. A score of 0.2 or below is considered as small, 0.3-0.7 as medium, and 0.8 or above as large. In this study, effect size statistics showed medium to large differ- ences in LSAS (Cohen's d = 0.93), COPE (Cohen's d = -0.63), positive emotions (Cohen's d = -0.52), negative emotions (Cohen's d = 0.83) and DAS (Cohen's d = 0.66) between participants of the experimental and control groups at post- test (Table 3). A correlation analysis was carried out to examine the relationships between DAS and other variables in this study. First, pretest and post-test mean differences in DAS, LSAS, COPE, and Positive and Negative Emotions of the CBT groups were calculated. A correlation analysis was then performed and revealed that DAS correlated sig- nificantly and negatively with positive emotions (r = -0.62, p < 0.001) and significantly and positively with negative emotions (r = 0.72, p < 0.001) [Table 4].

Discussion

Hypothesis 1 of the present study was confirmed, in that participants from the experimental group showed a lower level of social anxiety, more positive emotions, fewer nega- tive emotions, fewer dysfunctional beliefs, and more adap- tive coping skills, when compared with the members of the control group at the end of the group treatment. According to the cognitive model of social anxiety,37 the success of cognitive therapy for social anxiety lies in its effectiveness in modifying the dysfunctional cognitive processes of the persons involved. In our CBT groups, the content focused mainly on the identification and modification of negative automatic thoughts and dysfunctional rules and assumptions held by the members. Thus, the significant difference in DAS scores between CBT and control groups could be attributed to the knowledge and skills learnt through the group and homework exercises completed by members in the experi- mental group. Indeed, we designed a Chinese group manual that contained group exercise worksheets, homework worksheets, and easy readings that helped members under- stand and modify their own patterns of negative automatic thoughts and dysfunctional attitudes and assumptions. Besides, the mutual sharing and feedback from group mem- bers probably also played a powerful role in facilitating changes in members' thinking and behaviours. Throughout the group processes, members were encouraged to gently challenge one another's automatic thoughts and dysfunc- tional rules. They were also able to encourage one another to develop and practice new ways of thinking and behaving. Indeed, a number of studies have repeatedly demonstrated the therapeutic effects of CBT group treatment for people with various emotional disorders.38,39

The results provided preliminary evidence for the effect- iveness of CBT group treatment for Chinese people suffer- ing from social anxiety in Hong Kong. With a prevalence of 111,000 people potentially suffering from social anxiety in Hong Kong,40 this type of CBT group may serve as a pos- sible treatment alternative for people with such a mental health problem. However, future research is needed to collect evi- dence to support the longer-term effect of CBT for this group of socially anxious individuals. Moreover, this study cannot rule out the fact that positive changes in the various outcome vari- ables might have been due to the group effects such as emo- tional support and advice provided by other group members.

Hypothesis 2 of this study was partially confirmed. Results suggested that there were significant correlations between dysfunctional attitudes and positive and negative emotions among members of the experimental group. However, no significant relationships were found among dysfunctional attitudes, coping skills and social anxiety. One possible reason for this is that there was not enough time for the members in the CBT groups to practice the cogni- tive and behavioural skills learnt during the group sessions. Essentially, CBT strategies such as self-debating, thought stopping, positive self-talk and self-reward require a great deal of practice and feedback from others in order for the individuals to use them effectively to deal with their emotional problems.41 While our present group design is able to facilitate participants to understand their dif- ferent patterns of cognitive and behavioural responses and provide participants with two sessions to practise newly- acquired cognitive and behavioural strategies, much more time is probably needed for participants to gain positive experiences and competence in using the strategies in daily life. Indeed, previous studies found similar insignificant results in coping skills among Chinese people participating in CBT groups for people at risk of developing poor mental health and depression.23,24 Indeed, we recommend a second stage CBT group which aims at providing participants who have gone through the present CBT group with more time and feedback so that they can practise and consolidate the cognitive-behavioural strategies learnt in stage one.

This is one of the few documented studies of the appli- cation of CBT in Chinese people with emotional problems. Future studies need to examine closely the issue of indigenisation of CBT for the Chinese population. However, two initial observations are put forward here for future verification. Generally speaking, Chinese people are not used to expressing their opinions and emotions in front of strangers.42 In the group processes, we found that group participants expected the group leaders to provide a group structure for discussion and to facilitate such a discussion actively. However, once the group participants had gotten used to such an open atmosphere, they were able to discuss issues freely among themselves, and the group leaders could gradually facilitate the participants to take more control of group processes. These experiences tell us that initial strong encouragement by the group leaders may be necessary for Chinese participants to 'warm up' before they can venture to express themselves and their emotions. Moreover, the group leaders have to create the kind of atmosphere (i.e., set the tone) so that the participants understand that it is acceptable to express their opinions and emotions openly. On the whole, the group leaders have to be active and directive when working with Chinese people in groups. Our experiences also reveal that our group participants were not used to direct confrontation and were distressed by this when they had to confront or be confronted by others during the group processes. However, once a supportive atmosphere was established, the participants felt comfortable in con- fronting and being confronted by one another. Thus, the CBT approach, which requires the participants to face and modify their dysfunctional beliefs, seems to be suitable for use in Chinese subjects.

This study adopted a randomised waitlist control design to examine the efficacy of group CBT for Chinese people with social anxiety in Hong Kong. The results suggested that group CBT was able to help members reduce social anxiety and dysfunctional beliefs, and increase adaptive coping skills. Future studies should, first, increase the sample size so that more convincing evidence for the efficacy of cognitive therapy for people with social anxieties in Hong Kong can be collected. Secondly, it is necessary to introduce a comparison group such as an activity group to the study design because such an inclusion can isolate the influence of group effects, and possibly ascertain the effects of CBT treatment. Third, this study should include a follow-up assessment. Fourth, objective assessment such as a clinical assessment performed by a psychiatrist should be introduced in order to minimise the possible social desirability bias made by the participants in making posi- tive post-test responses. Although DAS has been used to measure cognitive functioning of people with anxieties, it is largely used on individuals with depression. Other more suitable instruments, such as the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale could be used instead.

References

- Petrocelli JV. Effectiveness of group cognitive behavioral therapy for general symptomatology: A meta-analysis. J Specialists in Group Work 2002;27:92-115.

- Cottraux J, Note I, Albuisson E, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy ver- sus supportive therapy in social anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69:137-46.

- Heimberg GH, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, et al. Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1133-41.

- Clark DM, Ehlers A, McManus F, et al. Cognitive therapy vs fluoxetine in generalized social phobia: a randomized placebo controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:1058-67.

- Hagen R, Nordahl HM, Kristiansen L, Morken G. A randomized trial of cognitive group therapy vs waiting list for patients with co-morbid psychiatric disorders: Effects of cognitive group therapy after treat- ment and six and twelve months follow-up. Behav Cogn Psychotherapy. 2005;33:33-44.

- Heimberg RG, Salzman DG, Holt CS, Blendell KA.Cognitive- behavioral group treatment for social anxiety: Effectiveness at five- year followup. Cognit Ther Res. 1993;17:325-39.

- Morrison N. Group cognitive therapy: treatment of choice or sub- optimal option? Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy. 2001;29:311-32.

- Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Hope DA, Liebowitz MR. Cognitive- behavioral group treatment: description, case presentation, and empirical support. In: Stein MB, editor. Social phobia: clinical and research perspectives. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995:293-321.

- Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, editors. Social phobia: diagnosis, assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1995:69-93.

- Rapee RM, Heimberg, RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:741-56.

- Heinrichs N, Hofmann SG. Information processing in social phobia: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:751-70.

- McManus F, Clark DM, Hackmann A. Specificity of cognitive biases in social phobia and their role in recovery. Behav Cogn Psychotherapy. 2000;28:201-9.

- Stopa L, Clark DM. Social phobia and interpretation of social events. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:273-83.

- Bond FW, Dryden W. Handbook of brief cognitive behaviour therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2002.

- Wells A, Matthews G. Attention and emotion: a clinical perspective. Hove: Erlbaum; 1994.

- Freeman A, Pretzer J, Fleming B, Simon KM. Clinical applications of cognitive therapy. New York: Kluwer Academic; 2004.

- Juster HR, Heimberg RG, Frost RO, Holt CS, Mattia JI, Faccenda K. Social phobia and perfectionism. Pers Indiv Diff. 1996;21:403-10.

- Lundh LG, Öst LG. Stroop interference, self-focus and perfectionism in social phobics. Pers Indiv Diff. 1996;20:725-31.

- Alden LE, Wallace ST. Social standard and social withdrawal. Cognit Ther Res. 1991;15:85-100.

- Lin YN. The application of cognitive-behavioral therapy to counseling Chinese. Am J Psychother. 2001;55:46-58.

- Lo HT, Lau Godwin. Anxiety disorders of Chinese patients. In: Lee E, editor. Working with Asian Americans: a guide for clinicians. New York: The Guildford Press; 1999:309-22.

- Lee JY, Choy CH. The effects of the cognitive-behavioral and expo- sure therapy for social anxiety. Korean J Counsel Psychotherapy. 1997; 9:35-56.

- Wong DF, Sun SY, Tse J, Wong F. Evaluating the outcomes of a cog- nitive-behavioral group intervention model for persons at risk of de- veloping mental health problems in Hong Kong: a pretest-posttest study. Res Soc Work Pract. 2002;12:534-45.

- Wong DF. Cognitive behavioral treatment groups for people with chronic depression in Hong Kong: a randomized wait-list control design. Depress Anxiety. 2007. Epub 2007 Mar 5.

- Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Turk CL. Managing social anxiety: a cognitive-behavioral therapy approach. New York: Therapy Works; 2000. 26.

- Beck J. Cognitive therapy: basic and beyond. New York: Guilford Press 1995.

- Scholing A, Emmelkamp PM. Treatment of generalized social anxiety: results at long-term follow-up. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:447-52.

- Liebowitz MR. Social anxiety. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987; 22:141-73.

- Liebowitz MR, Heimberg RG, Schneier FR, et al. Cognitive-behav- ioral group therapy versus phenelzine in social anxiety: Long term outcome. Depress Anxiety. 1999;10:89-98.

- Fresco DM, Coles ME, Heimberg RG, et al. The Liebowitz Social Anxi- ety Scale: a comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered format. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1025-35.

- Cormier LS, Hackney H. The professional counselor: a process guide to helping. NJ: Prentice Hall; 1987.

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretical based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267-83.

- Lam HS. Examining Chinese health beliefs and coping strategies in influencing delays in help-seeking behaviors of carers with relatives suffering from early psychosis. Unpublished Master of Social Science (Mental Health) dissertation, Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 2003.

- Weissman AN, Beck AT. Development and validation of the Dysfunc- tional Attitude Scale: a preliminary investigation. Presented at the meet- ing of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Chicago, 1978.

- Beck AT, Brown G, Steer RA, Weissman AN. Factor analysis of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale in a clinical population. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:478-83.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988.

- Beck AT, Clark DA. An information processing model of anxiety: automatic and strategic processes. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:49-58.

- Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Bruch MA. Dismantling cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:637-50.

- Stangier U, Heidenreich T, Peitz M, Lauterbach W, Clark DM. Cogni- tive therapy for social anxiety: individual versus group treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:991-1007.

- Hong Kong Mood Disorder Centre. Available from: http://www.hmdc. med.cuhk.edu.hk.

- Cormier S, Cormier B. Interviewing strategies for helpers: fundamen- tal skills and cognitive behavioral interventions. New York: Brooks/ Cole Publishing Company; 1998.

- Cheung G, Chan C. The Satir model and cultural sensitivity: a Hong Kong reflection. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2002;24:199-215.